-

Magazine No. 33

Frei Otto

-

No. 33 - Frei Otto

-

page 02

Cover

Frei Otto

-

page 03

Editorial

Frei Otto

-

page 05

The Last Word First

-

page 06 - 10

The Lightness of Being

Frei's thought bubbles

-

page 11 - 18

Frei by Name, Frei by Nature

A life extraordinary by Irene Meissner

-

page 19

True to Type

Otto experiments with typography

-

page 21 - 23

Halle-luja

The Mannheim Multihalle, 1975

-

page 24 - 34

The Stuttgart Boys

Frei association: bionics, parametrics, morphogenics and more… by Sophie Lovell

-

page 36 - 37

Paperweight

Japanese Pavilion, Hanover Expo 2000

-

page 38 - 39

Heart of Lightness

Diplomatic Club, Saudi Arabia, 1985

-

page 40

The Fast and the Curious

Otto experiments with mobility

-

page 41 - 47

Otto and the Open System

Georg Vrachliotis in conversation with Jean-Philippe Vassal

-

page 48 - 49

Featherweight

Hellabrun Zoo Aviary, Munich, 1980

-

page 50

When Frei met Bucky

A meeting of like minds

-

page 52 - 55

Reflections of an Enquiring Mind

Otto’s archive of ideas

-

page 56

Wood Works

Otto experiments with furniture

-

page 57 - 58

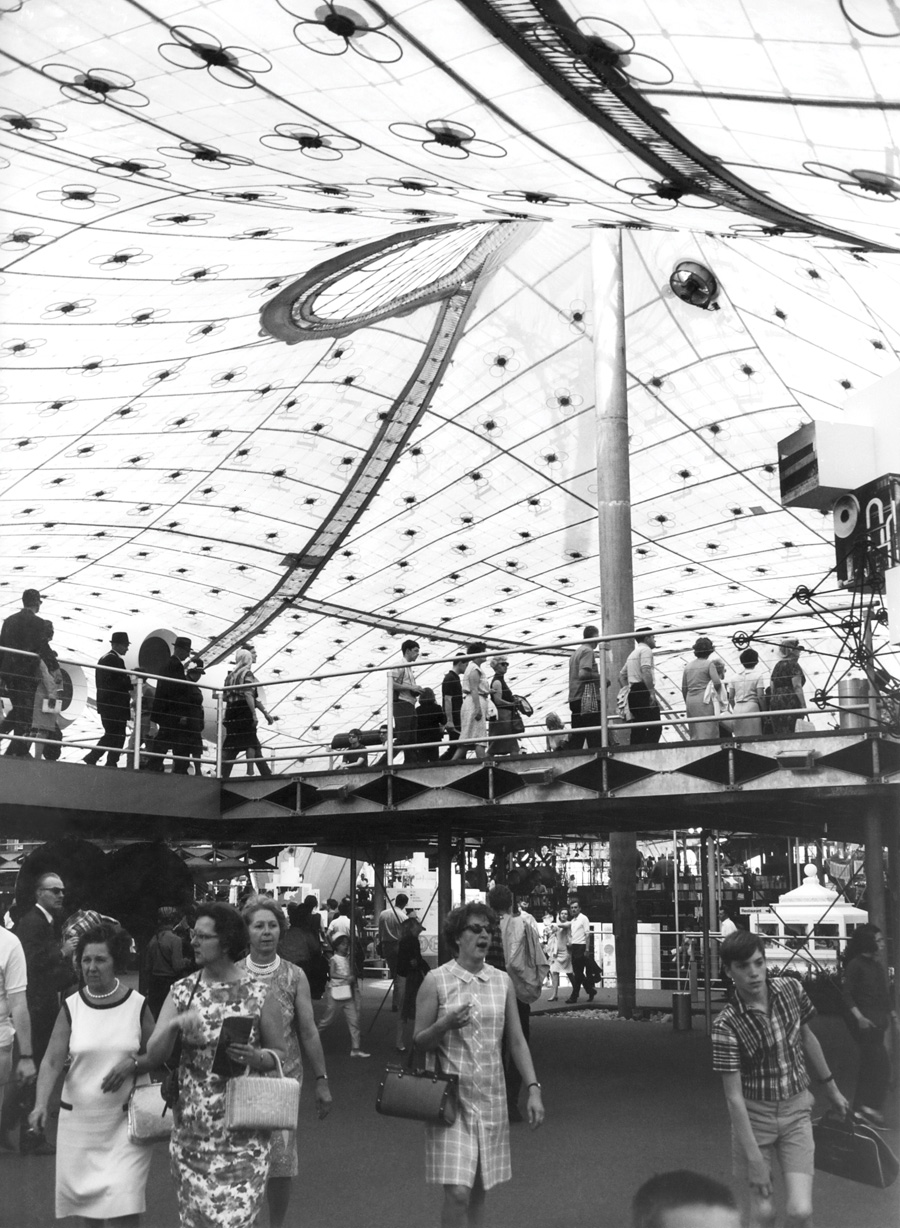

Flyweight

West German Pavilion, Montreal Expo 67

-

page 59 - 65

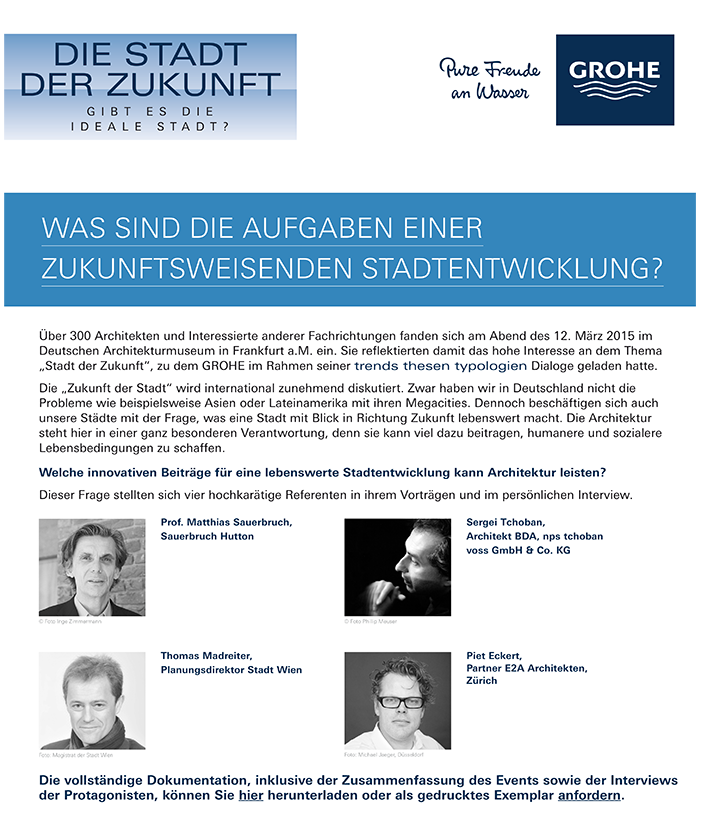

Honouring Otto

Focus on Frei Otto by his peers and colleagues

-

page 66 - 67

Moving Mountains

Olympic Stadium, Munich, 1972

-

page 68

Blow Up

Otto experiments with pneumatics

-

page 69 - 74

Twenty Feet from Mies to Frei

Mies student and Otto disciple Conrad Roland

-

page 75

Arctic City

Otto experiments with environments

-

page 76

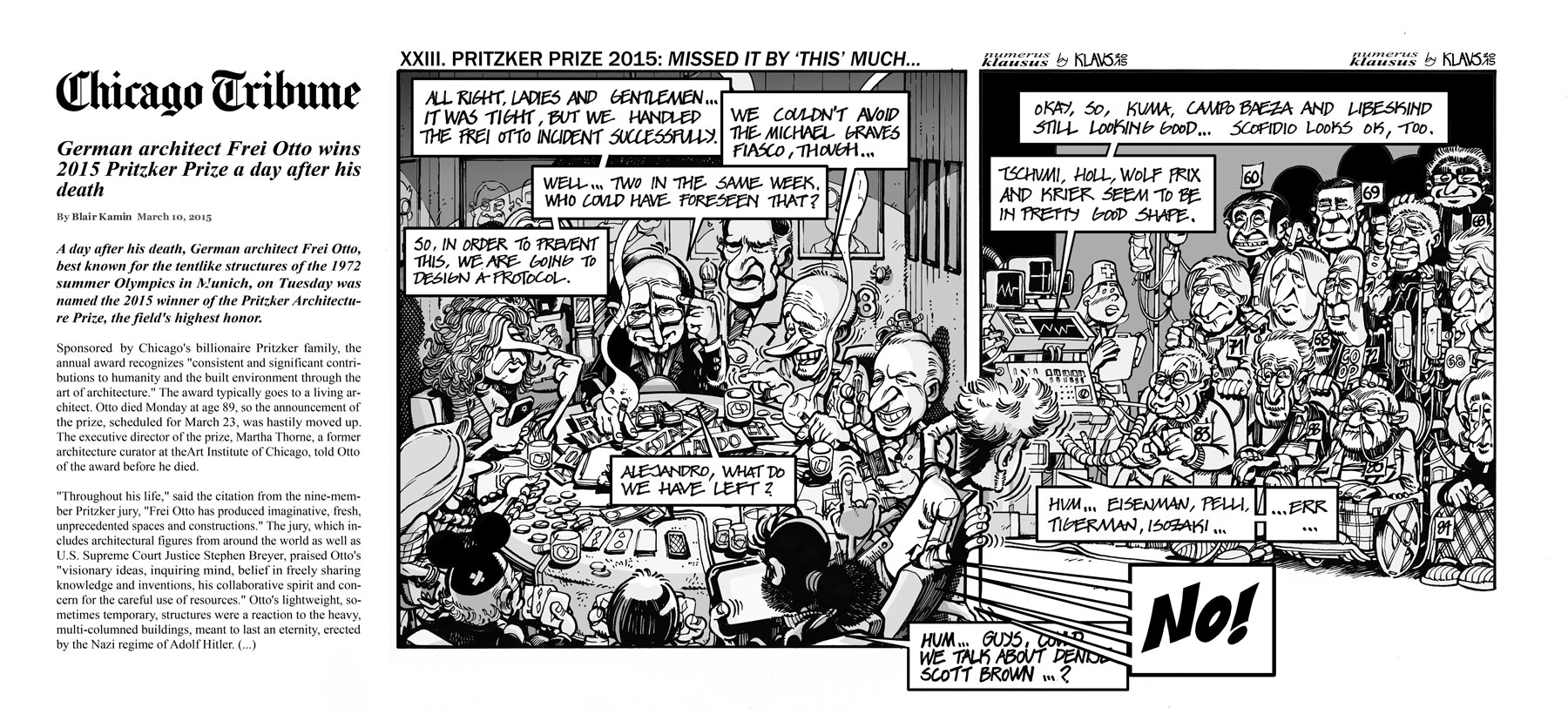

Klaustoon

XXIII. Pritzker Prize 2015: Missed It By 'This' Much...

-

page 77

Next

Commune Revisited

-

-

uncube's editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer (fh), Rob Wilson (rgw) and Fiona Shipwright (fs); editorial assistance: Sara Faezypour (sf); graphic design: Lena Giovanazzi; graphic assistance: Diana Portela. Translators for this issue: Alisa Kotmair and Christine Wolfe.

uncube is based in Berlin and published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online portal covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

Frei Paul Otto was a man after uncube’s own heart, with an œuvre stretching far beyond architecture.

With this, perhaps our lightest issue yet – but with the content of a small book, uncube brings some surprising insights into the versatility of the 2015 Pritzker Prize winner, who died aged 89 on March 9, this year. He was an investigator and inventor, combining the fields of engineering, biology, architecture, and design.

Far more than a simple retrospective homage, the thoughts, anecdotes and observations collected here, many from those who knew him, are an inspiration – reflecting the legacy of a man whose mother prophetically named him: “Free”.

Be experimental! Be radical! Be Frei!

Special thanks to Jürgen Paul‚ the ILEK archive, to Georg Vrachliotis and the saai archive, and to Oliver Elser and the DAM archive.Cover image: Frei Otto busy form-finding. (Photo: © ILEK, Stuttgart) This page: Frei at IL (Film (no audio): © ILEK, Stuttgart)

-

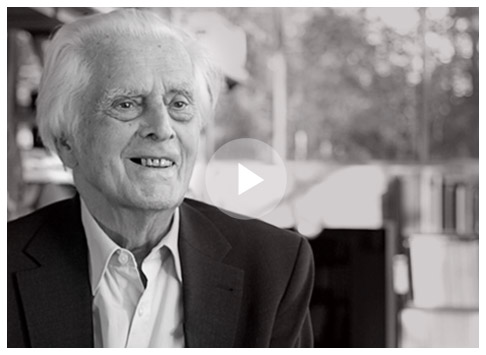

The last word first: the executive director of the Pritzker Architecture Prize committee Martha Thorne travelled to Frei Otto’s home and studio in Warmbronn to inform him that he had been named the 2015 Pritzker Prize Laureate. Here, in his last filmed interview, recorded shortly afterwards, he reflects upon his achievements, a self-proclaimed “happy man”.

Video: © The Pritzker Architecture Prize / The Hyatt Foundation; directed by Edward Lifson.

![]()

-

The Lightness of Being

Frei’s thought bubbles

-

![]()

»I have built little. But, I have built many castles in the air.«

![]()

Documentation of Otto’s pneumatic experiments with rubber forms and soap bubbles.

(All photos: © ILEK, Stuttgart)

-

»We can build houses which are two or three kilometres high and we can design halls spanning several kilometres and covering a whole city but we have to ask what does it really make? What does society really need?«

Quote source this and following pages: Otto in conversation with Justin McGuirk, ICON, 2005

-

»Using air as a building material means that the amount of material you need is very minimal so you can dedicate your forces to the relation between animals and man, and man and plants, and make an environment which is in equilibrium.«

-

»The secret, I think, of the future is not doing too much. All architects have the tendency to do too much.«

-

![]()

A life extraordinary

By Irene Meissner

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

With his lifetime achievements, Frei Otto gave German architecture after 1945 an international relevance like no one else. Writer and curator Irene Meissner, co-author of a forthcoming book on Frei Otto, gives an introduction to the life, works and inspirations of this extraordinary architect.

Frei Otto, born in 1925, was the son of a stonemason and sculptor and belonged, by his own account, to a generation “shot into adulthood by the war”, who afterwards “wanted to get over the war, the megalomania, the cult of the Führer and of personality”. Many of his key ideas can be traced back to his formative experiences.

His unusual Christian name “Frei” (Free) was his mother’s invention. To be free was her philosophy in life, one she certainly passed on to her son. Frei Otto possessed a spirit that was free, critical and independent. As a teenager he was fascinated by gliders, but after secondary school, enrolled at the Technical University in Berlin to study architecture. However, with the Second World War, he was drafted into the German air force, and as a fighter pilot witnessed how buildings planned for the “new eternity” of the Third Reich disintegrated beneath the downpour of bombs. Later as a prisoner of war near Chartres, France from 1945 to 1947, he became camp architect, where, constrained by the scarcity of building materials, he taught himself the basics of simple lightweight construction.

In 1947 Otto resumed his architecture studies in Berlin and in 1950 travelled to the United States as a fellow of the German National Academic Foundation. At the office of Fred Severud he saw the suspended roof construction for the Raleigh Arena in North Carolina by Matthew Nowicki, which was to become a key source of inspiration for his future creations. In 1954 he presented his own research in the field of tensile, cable net construction in his groundbreaking dissertation entitled: The Hanging Roof.Previous page: Otto shooting his model design concept for Berlin Olympic Stadium’s grandstand roof, 1970. (Photo: © Fritz Dressler, Worpswede)

-

Photo: © ILEK, Stuttgart

![]()

-

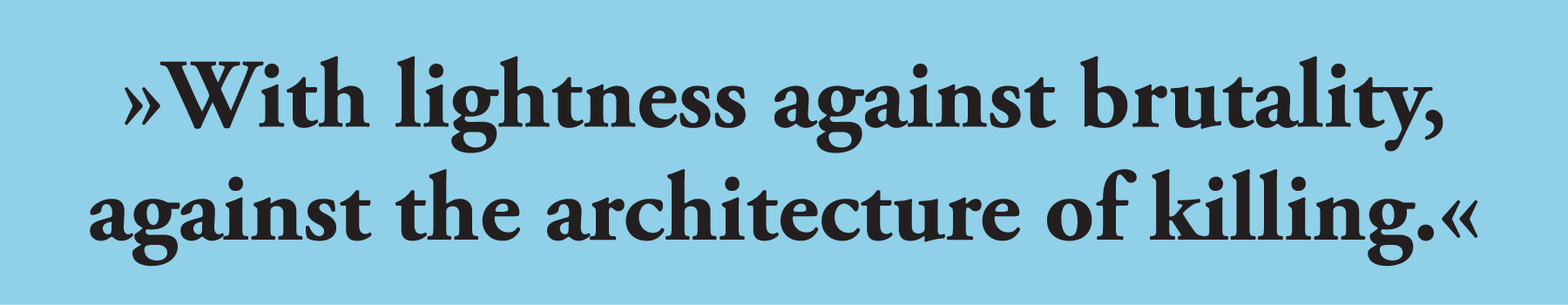

After the First World War, Bruno Taut countered a world gone awry by proposing his Alpine Architecture project – in which he proposed that new world harmony would be created by uniting nature, glass and crystal – similarly, Otto, after the Second World War, developed a vision for a people-oriented architecture in harmony with nature, deriving its form from the laws of nature itself. He experimented with materials that had not previously been considered as building materials, such as fabrics and air. Not only was Otto exploring uncharted territory, but he also offered a new architectural approach that diverged radically from the Nazi era. He countered sombre, massiveness, axiality and symmetry with lightweight, floating, asymmetrical forms that oriented themselves to the individual with agility and adaptability. “With lightness against brutality” and against the “architecture of killing” were a couple of expressions with which Otto succinctly summed up his driving concept.

![]()

1.

![]()

3.

![]()

2.

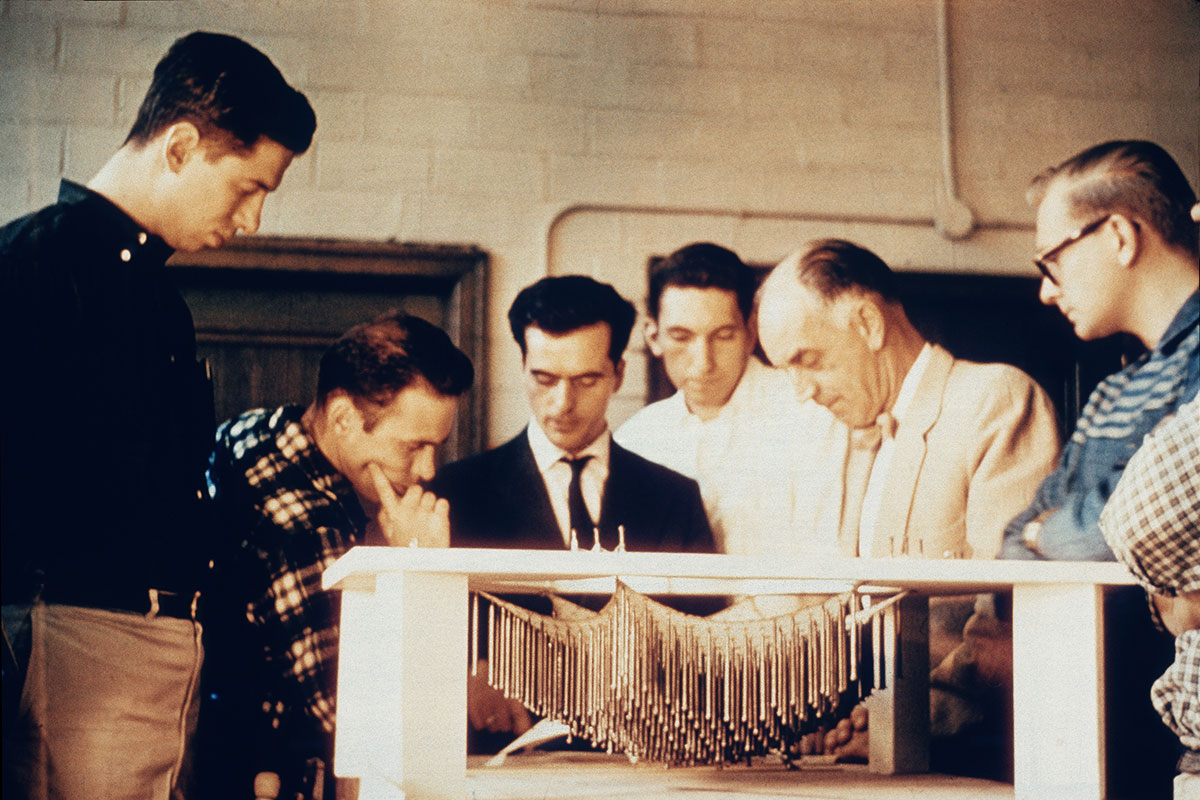

1. Otto leads a seminar on lightweight structures in 1958 at Washington University, St Louis, Missouri. (Photo: © ILEK, Stuttgart);

2. Otto busy testing new forms inside... & 3. ...outside. (Photos: Carsten Schröck) -

Otto in the garden of EL, Berlin, with a net model of his reworked construction plan for Behnisch & Partner’s Munich Olympic Park concept, 1968. (Photo: © Fritz Dressler, Worpswede)

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Otto built his first tensile structures in 1955 together with the tent-maker Peter Stromeyer for the Federal Horticultural Exhibition in Kassel. Their music pavilion there was a four-point, saddle-shaped shade sail, with stability provided by a membrane spanned between two high and two low points. Its aesthetic quality was even lauded as an artwork at the first Documenta, which was running concurrently in Kassel. In the following years, Otto took membrane construction to new heights, elevating it to a recognised architectural form. Through his numerous wave-, dome-, pointed- and humpbacked-tent forms he explored the potential of this building technique, and in the process discovered that membranes could not be designed per se, but that their forms emerged within a given framework of parameters in a natural process of form-finding.

In 1958, as a visiting professor at Washington University in St. Louis, Otto discovered in the work of Richard Buckminster Fuller a fellow protagonist of lightweight, adaptable construction and a shared belief in its ability to improve the quality of life. Like Otto, Fuller was interested in achieving maximum efficiency with a minimum expenditure of materials and energy. While Otto derived his insights from biology – looking to the cell as nature’s smallest building block – Fuller was experimenting with octahedrons and tetrahedrons based on geometric chemical molecules, which he composed into structures like the geodesic dome, both aimed at creating better human living conditions. Otto pursued similar ideas and as early as 1953 drafted speculative plans for a town in Antarctica built beneath a cable net dome.

Otto conducted his early research in Berlin at the “Development Centre for Lightweight Construction” (EL), which he privately founded in 1958. In 1964, upon the recommendation of engineer Fritz Leonhardt, he was invited by the Technical University in Stuttgart to head their newly established “Institute for Lightweight Structures” (IL). An initial success of the Institute’s intensive research on cable net constructions was the competition submission Otto developed with Rolf Gutbrod for the German Pavilion at the 1967 World Expo in Montreal. The prototype they built in Stuttgart for this internationally celebrated construction, with its minimal surface area and a cable net spanning between high and low points, would later come to house Otto’s increasingly celebrated institute. The “tent” in Montreal served as inspiration for the architects Behnisch & Partner in their competition submission for the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. The solution for the planned rooftop, delicately floating across the landscape, came from Frei Otto. He worked with a team of experts, including Fritz Leonhardt and Jörg Schlaich, to develop the cable net roofs, which still garner worldwide attention today. -

Following on from his development of membrane and cable net structures, Frei Otto turned his attention to arches, grid-shells and vaults. Notable was the Multihalle in Mannheim from 1974, a groundbreaking building that combined a form naturally evolved from its timber gridshell with immense flexibility. He also studied natural structures and the form-finding processes inherent in branches, pneumatic and large shell structures, and constructive technology’s origins in the shapes of nature became a running theme in the work of the IL. In 1960 Frei Otto met the biologist and anthropologist Johann-Gerhard Helmcke in Berlin, who introduced him to organic self-formation processes. After that, Otto was devoted to understanding natural processes and structures and applying their principles to load bearing architectural constructions. In 1984 he set up a special research project on “natural constructions” at the IL. The project resulted in a unique synergy as scientists from diverse fields shared and collaborated on theories, experiments and research. This fruitful form of cooperation yielded several inspirational symposia and publications, making Frei Otto’s Institute the most vibrant and creative research centre in Germany, with an international reach.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Otto presenting, listening, and talking at an outdoor seminar in 1968. (All photos: © ILEK, Stuttgart)

-

Irene Meissner is an architectural engineer, writer and curator at the Architekturmuseum der TU München. One of the contributors to the book Frei Otto, The Complete Works (2005), she is the author with Eberhard Möller of Frei Otto – forschen, bauen, inspirieren (Frei Otto – A life of research, construction and inspiration), which will be published by DETAIL, Munich in May 2015 and was originally planned as a tribute to Otto on his 90th birthday.

The book has a contribution by Georg Vrachliotis of saai – the Southwest German Archive for Architecture and Civil Engineering – to which in 2010 the State of Baden-Württemberg entrusted the archive of Frei Otto’s works after its acquisition.

irene-meissner.de

architekturmuseum.de

![]()

For Frei Otto, the role of the architect was as a mediator between people and their habitat, whose duty was the “preservation of the biotope”. His approach drew from the social approach of the Neues Bauen (New Building) movement from the Weimar Republic, which included Bruno Taut’s vision of the earth as a “good dwelling”. Long before the environmental movement and the establishment of “green” parties, he recognised and conducted fundamental research on the problems of our environment. At the height of post-war reconstruction in Germany, Otto called attention to misguided developments in architecture, such as the squandering of resources on purely profit-driven building. In a highly regarded speech he made in 1977 at the Schinkelfest in Berlin, he vehemently criticised his colleagues and demanded: “Stop building the way you build! It is unnatural!” He discussed alternative solutions at IL symposia on “natural building” and demonstrated his vision of an ecologically-based and participatory architecture with his eco-houses built for the 1987 International Building Exhibition in Berlin.

In the catalogue for the exhibition on Otto’s work, presented in 2005 at the Architecture Museum of the Technical University in Munich, Norman Foster aptly summed up his importance: “As much, then, as his extraordinary sequence of works altered the nature of architectural form in the twentieth century, his environmentalism, intelligence, and foresight have established the defining architectural mentality for the twenty-first. He is an inspiration.” I

![]()

Photographing the competition model for Berlin’s Olympic Stadium roof, 1970. (Photo: © Fritz Dressler, Worpswede)

-

Frei Otto was still a student at the Technical University in Berlin in 1950 when he started to design his own typeface “Atelier Warmbronn”. The font’s organic, flowing lines reflect the sensuality and smoothness that so fascinated the design process of its designer – recalling the work of German anthroposophist and typographer Walther Roggenkamp who was similarly inspired by the interest in Rudolph Steiner at the time. When Otto founded his own studio in 1952, he decreed Atelier Warmbronn as the official typeface. This was at a time when all labelling was still prepared by hand, using stencils and fountain pens. The font was affectionately referred to by his colleagues as “Würmchenschrift” (“Worm Type”).

Over the years, different refinements of the typeface were used in books and for cover designs until, in the 1980s, Atelier Warmbronn was digitalised for computer use. From then on Otto even used it to type his letters. Throughout his entire life Otto remained surprisingly devoted to his strange, worm-like script. I (Franziska Stein)

TRUE TO TYPE

-

![]()

Halle-lujaThe Multihalle

Mannheim, Germany 1975

Carlfried Mutschler, Joachim Langnerand Frei Otto

![]()

-

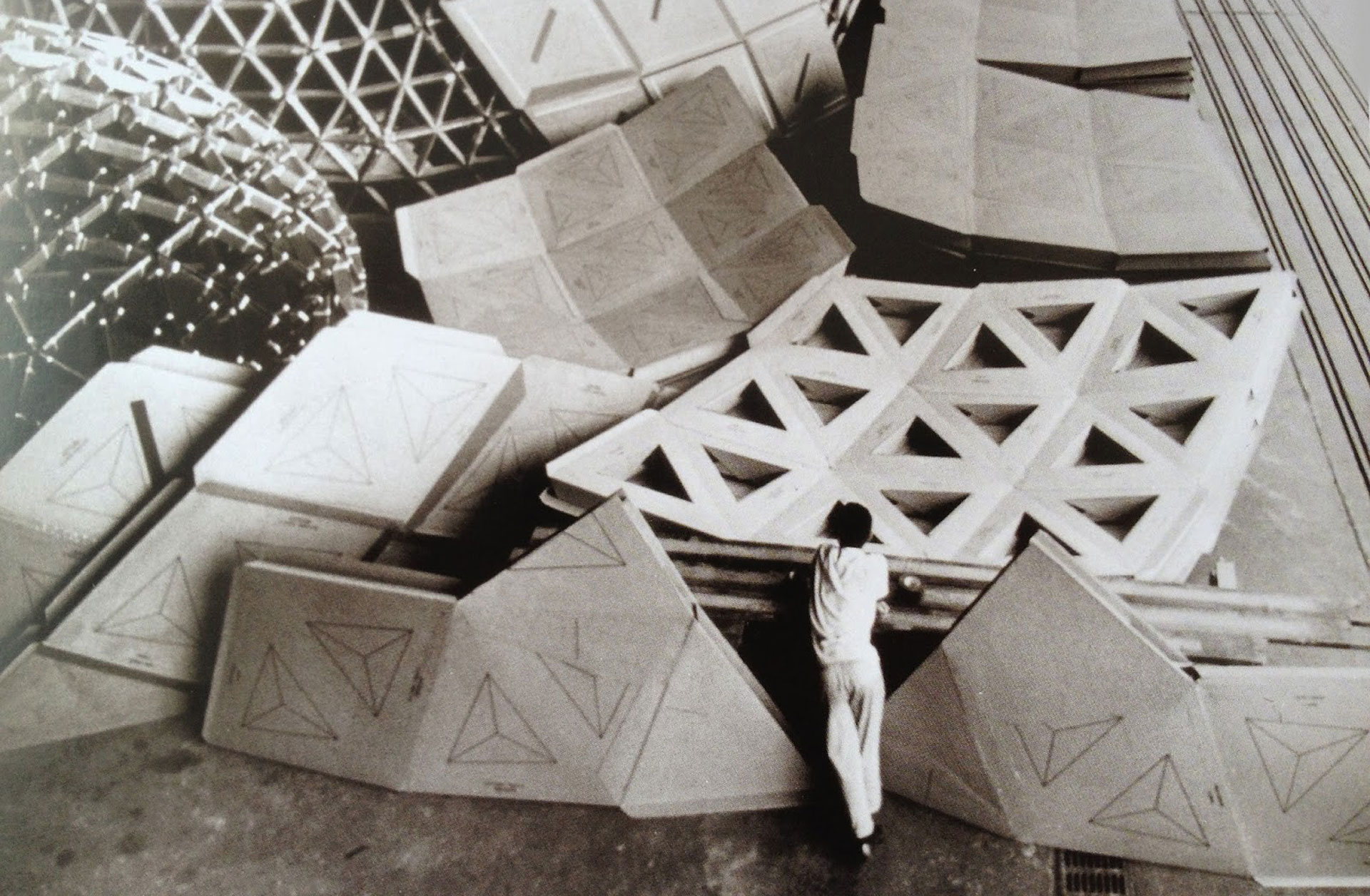

The Mannheim Multihalle, designed as a temporary structure for the 1975 Bundesgartenschau (Federal Horticultural Exhibition), is now forty years old. It has been incredibly influential in the field of contemporary biomorphic architecture: a forerunner to a generation of computer-generated blobs and bubbles that have appeared on screens – and in construction – since. Yet few have approached the elegant sophistication of its spectacular super-wide-span lightweight structure. The free-flowing curved timber gridshell spanning up to 60 metres and reaching up to 20 metres in height was the result of years of research by Frei Otto and one achieved without the need for complex foundations. Whilst the structural efficiency of the gridshell won over engineers, the public were equally captivated by its transparency.

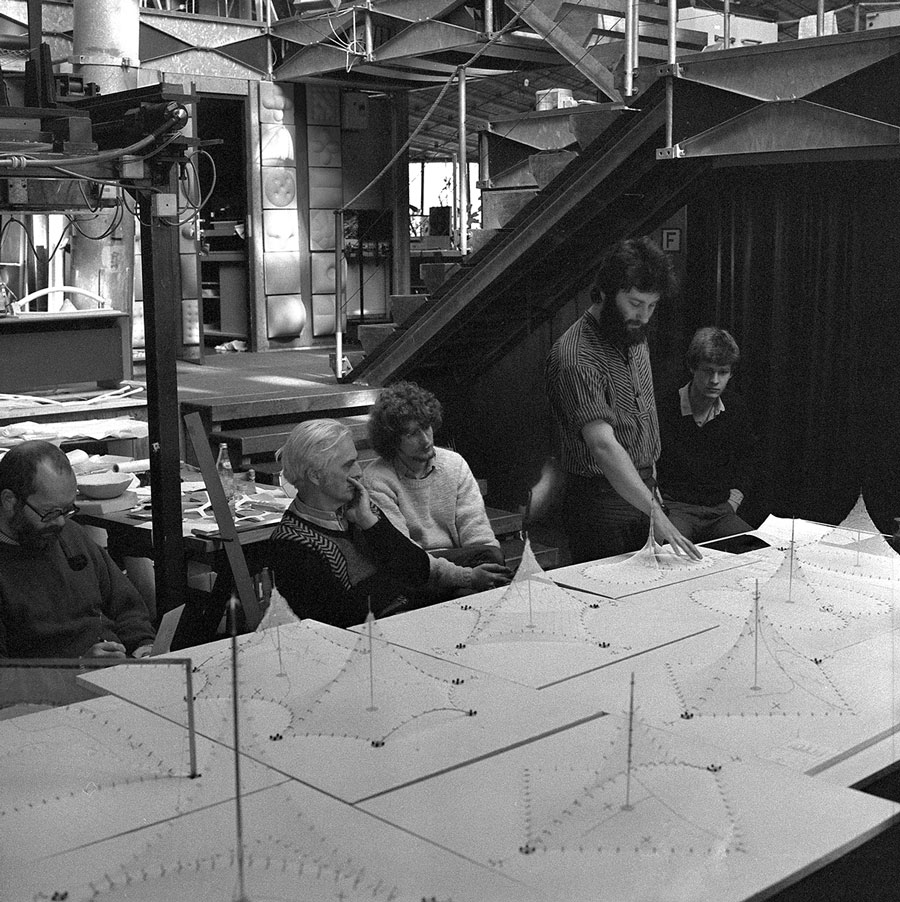

In addition, the material-saving and sustainable construction techniques that it pioneered are themes that are even more topical today. A number of elaborate physical models were made in order to define the form of the building’s shell. In particular, Frei Otto had a large model built at a scale of 1:98.5, using the inversion principle used by Antoni Gaudi in his design for the Sagrada Família. Otto’s assistants constructed the hanging net of this model by hand from 15 millimetre-long wire rods linked by hooks to 2.5 millimetre-diameter wire rings. This was then photogrammetrically measured and the data fed into a CDC 6600 – the “mainframe” computer of its day – generating an initial spatial, digital model, which was then outputted on a so-called “plotter” at 1:125 scale: producing CAD drawings that were among the first examples in the history of architecture.

![]()

All images: the Multihalle in 1975. (All photos: Heinrich Klotz, courtesy of DAM and Heinrich-Klotz-Bildarchiv, HfG Karlsruhe)

-

Christiane Weber is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Architectural History and Theory at the Leopold-Franzens University in Innsbruck, Austria and currently holds the Feodor Lynen Fellowship awarded by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. She studied architecture at the University of Karlsruhe and at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture in Paris-Belleville, as well as, in parallel, architectural history and theory at the University of Karlsruhe and the University of Strasbourg. Her research has included studies into the experimental models of Frei Otto.

Finally, after all these model tests, in the winter of 1974, forklift trucks began hoisting the two-ply lattice shell sections into place. And on January 30, 1975 the structure passed the load testing of its innovative construction, when 205 rubbish containers filled with water were hung from its gridshell.

However the years have taken their toll on a structure that was only ever intended to be temporary. Its transparent, PVC-coated polyester fabric covering was replaced with a white Teflon membrane after seven years, but this has since sustained damage, necessitating closure in 2011. There has been talk of demolishing the building over the years due to high energy costs, but after being designated a cultural landmark in 1998, in 2012 the city of Mannheim declared its intention to preserve the Multihalle for posterity. Multi-halle-uja.![]() (Christiane Weber)

(Christiane Weber) -

![]()

Frei association: bionics, parametrics, morphogenics and more…

By Sophie Lovell

-

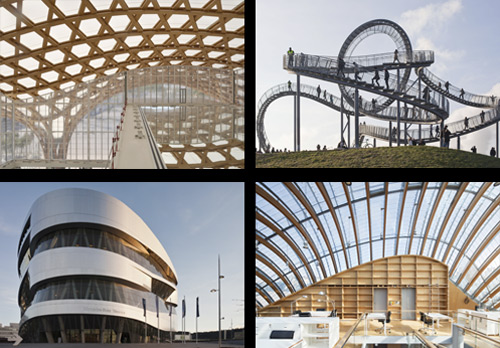

The Centre Pompidou-Metz, Paris (2008), Tiger and Turtles - Magic Mountain, Duisburg (2011), The Mercedes Benz Museum, Stuttgart (2005), The Pathé Foundation Headquarters‚ Paris (2014).

The architect Arnold Walz was born in Stuttgart in 1953. He studied at the University of Stuttgart in the 1970s and early 1980s and taught at the Institute of Computational Design there (founded in 2009) from 2009-11. Walz was a pioneer in the use of CAD parametric models for construction planning and has designed structural elements for a number of significant buildings, including the double-helix-formed Mercedes Benz Museum in Stuttgart, designed by UN Studio and the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, designed by Renzo Piano. He is a partner in the firm designtoproduction.

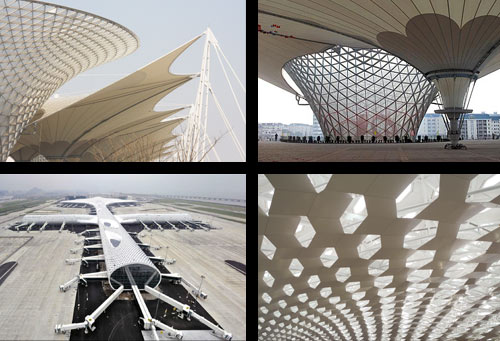

Shenzen Airport (2013) and the Shanghai Expo axis (2010).

Jan Knippers was born in Düsseldorf in 1962 and studied engineering at the Technical University in Berlin during the 1980s. Afterwards he worked for Schlaich Bergermann and Partner in Stuttgart until 2000, when he became Head of the Institute of Building Structures and Structural Design, or ITKE, at the University of Stuttgart. He is a bionics specialist and speaker at the Collaborative Research Center for Biological Design and Integrative Structures there too. Every year since 2010, his students have collaborated with those of Achim Menges at the Institute for Computational Design (ICD), pooling their interdisciplinary talents to create full-sized “research pavilions” on the university campus that blend bionics with computer-aided manufacturing.

Knippers is also partner in the firm Knippers Helbig Advanced Engineering and has worked on projects such as the façade of Shenzhen Airport, the membrane megastructures in the main boulevard of the Shanghai Expo 2010 and the façade of the Palais Quarter in Frankfurt.

knippershelbig.com

Housing prototypes H16 (2006) and R128 (2000).

The architect and engineer Werner Sobek took over from Frei Otto as head of the Institute for Lightweight Structures (IL) in 1994 and in 2000 followed his mentor, the engineer Jörg Schlaich, as Head of the Institute for Construction and Design as well. He then merged the two institutes into a single one: the Institute for Lightweight Structures and Conceptual Design (ILEK), which he still heads up today.

Sobek was born in Aalen, Germany in 1953 and studied architecture and structural engineering in parallel at Stuttgart University between 1980 and 1986. He is a strong advocate of sustainability and is best-known for his experimental self-sufficient housing prototypes such as R128 and H16. He also has his own company with some 200 employees designing in a broad range of materials and structural-types.

wernersobek.com

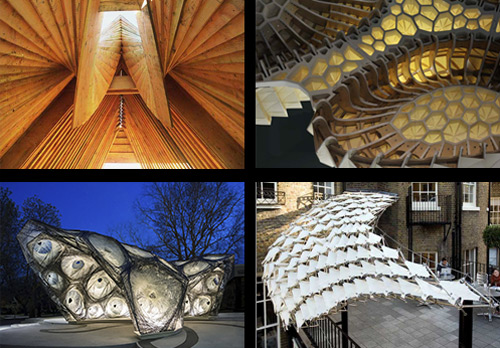

Patagonia Shelter (2007), HygroSkin: Meteorosensitive Morphology (2012), ICD/ITKE Research Pavilion (2014), AA Component Membrane (2007).

Architect Achim Menges was born in 1975 and is a graduate of the AA School of Architecture in London. He taught there and at the HfG Offenbach School of Architecture and Design before going on to found and head up the Institute for Computational Design (ICD) at the University of Stuttgart in 2008. Menges’ practice and research focuses on the development of integral design processes at the intersection of morphogenetic design computation, biomimetic engineering and computer-aided manufacturing. Each year, since 2010, his students have collaborated with those of Jan Knippers’ Institute of Building Structures and Structural Design (ITKE), pooling their interdisciplinary talents to to create full-sized “research pavilions” on the university campus that blend bionics with computer-aided manufacturing.

achimmenges.net

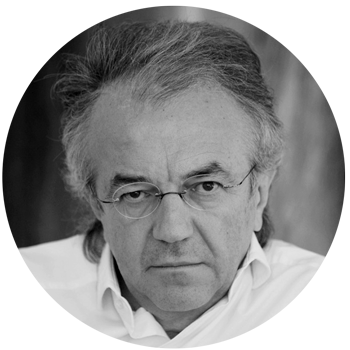

In 1964, the pioneering structural engineer and Head of the Institute for Concrete Structure, Fritz Leonhardt, lured Frei Otto to the University of Stuttgart to be professor of a new research department. Otto followed an illustrious roll call of pioneering structural engineers there – but as an architect, his arrival marked an extraordinary flowering of new interdisciplinary research-driven innovation. Sophie Lovell spoke to four of Stuttgart University’s leading engineering and architecture professors about Frei Otto’s impact there, on how his symbiosis of architecture and engineering has continued to develop since – and where it’s headed next…

Previous page: Leichtbau BW installation, produced by the University of Stuttgart’s Institute for Computational Design (ICD) and the Institute for Building Structures and Structural Design (ITKE) for 2014’s Hanover Fair. (Photo: courtesy Achim Menges/ICD)

-

Deep Surface Prototype: a project by Boyan Mihaylov, Viktoriya Nicolova, Achim Menges and Sean Ahlquist at the ICD. (Photo courtesy Achim Menges/ICD)

-

Frei days at Stuttgart

Stuttgart is famous for being in Germany’s engineering heartland: the cradle of the automobile industry and other precision engineered manufacturing, like Daimler, Porsche and Bosch. The University is renowned as a centre for automotive and aerospace engineering – areas where “lightweight” was already of primary concern. As an investigative architect Otto brought his interdisciplinary thinking into an environment ripe for pushing boundaries.

During Frei Otto’s time at Stuttgart, heading up the Institute for Lightweight Structures between 1964 and 1991, there were a number of influential professors there, besides himself, who contributed to a climate of future-oriented research thinking in the early years and a strong cross-over between architecture and engineering. Werner Sobek, Jan Knippers and Arnold Walz all studied there during this period. As architect Arnold Walz recalls: “Two people at Stuttgart had a great influence on me: Frei Otto, and Horst Rittel – who was in charge of the Planning Institute, taught at Berkeley and had been the last Rector at the HfG Ulm. What Otto and Rittel had in common was their fundamental attitude. They weren’t interested in details but in basic understanding. For Otto it was the relationship between form, materials and construction. While Rittel was a very radical thinker: he taught me to think and not to be afraid of doubt. With these basics you can go a long way and are more likely to create something new.”

Jan Knippers, like Otto, first studied engineering at the Technical University in Berlin, and found it frustratingly conventional. He moved to Stuttgart to work with Jörg Schlaich – one of Germany’s most important engineers – and immediately encountered a totally different spirit: “At Stuttgart, engineering was very much embedded in a cultural, societal and scientific context – much more advanced and more open, with the relationship to architecture much stronger”, he recalls. The proximity for these architects and engineers to the automotive and other local engineering industries meant they were in an environment where inventiveness and economy of materials were common practice.

Werner Sobek, who studied both engineering and architecture at Stuttgart, is head of ILEK: a merging of Frei Otto’s IL Institute and Jörg Schlaich’s Institute for Construction and Design, both professorships of which he inherited from his predecessors and mentors. -

“We were very lucky”, he says, “that in Stuttgart in the early 1960s there were a few professors in the Departments of Architecture and Engineering who were looking for closer cooperation. From then on there was what we now call ‘the Second Stuttgart School’, which blossomed between 1960 and about 1980. The influences emanating from this school were very important: it bridged the gap between architecture and engineering and widened the focus out into aircraft design, car body design, textiles and more.”

Fire and Water

It may have been a bonding moment between architecture and engineering, but this was not without its frictions. Not least between “architect” Otto and “engineer” Jörg Schlaich. “They appreciated each other, but nonetheless each had their distinctive field of research, which sometimes seemed like fire and water”, says Sobek. It seems the main trigger for the differences between these two research institute heads was when they both worked on the 1972 Olympic stadium project – Otto as consultant to the architect Günter Behnisch, and Schleich as chief engineer working for the company of another legendary Stuttgart professor, Fritz Leonhardt. According to Arnold Walz, Otto was more interested in exploring the boundaries of lightweight and elasticity with the roof: “But Schlaich couldn’t deal with this. I’m not sure if it was just his way of thinking or the building regulations you had to follow at the time. He wanted to make the structure as stiff as possible, like a concrete structure. Therefore all the parts grew in size and diameter. Maybe this is the reason the roof is still there. If Otto had been allowed to do the optimisations he wanted to, perhaps corrosion or other little things might have already destroyed the structure.”Otto frei Stuttgart

Jan Knippers says he had never heard of Frei Otto whilst he was studying engineering in Berlin. “But in Stuttgart I realised how important he was, because of his impact on the interface between architecture and engineering. He was someone who had a lot of charisma, and a lot of ideas that were then taken up and worked on by others. I soon realised that many of the things that were later being worked on at the ITKE institute, came originally from Otto’s ideas: membranes, lightweight building, rope nets, grid shells and so on.”![]()

-

![]()

Photo: Detail of the robotically wound carbon and glass fibre strcuture of the 2012 ICD/ITKE research pavilion. Video: footage of the winding robot in action. (Photo courtesy ITKE; Video: courtesy ICD)

-

Experimental structure R129, designed under the supervision of Werner Sobek by his then doctoral student, Dr Lucio Blandini, between 2002-05. (Photo courtesy ILEK)

-

“He was not an architect, but a thinker”, says Sobek, “and the only lifelong professor in the entire university who did not have to teach: he was totally free of that… He’d often surprised everyone by arriving with some biologists from Berlin, for example, to compare mussel shells with concrete shells, or human bones with steel columns. This permanent jumping over fences, or even not accepting that there was a fence between disciplines, was very important at the time. He did not just jump the fence, he tore it down.”

Achim Menges, who did not move to Stuttgart until 2008, says the effects of Otto’s presence there are still felt: “I think the main impact of his work on our approach is that he really questioned established models of design. His radical revision of the design process through what he called ‘form-finding methods’ is really something we’re trying to extend into the computational realm.”![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Slideshow illustrating the development and construction of the ICD/ITKE’s 2011 research pavilion, a wooden structure inspired by the biological form of a sea urchin’s plate skeleton. (Photos: courtesy ITKE)

Otto’s Influence

“Although he built little, Frei Otto had an incredible influence on architecture”, says Jan Knippers, “because he developed a whole new approach to the idea of design. Form and structure are not defined by architects, but arise through physical structural principles. And this is what we’re continuing now – but on another level. Structures and forms are now performance-driven. As in biology, there is no longer the hierarchical differentiation between structure and material.”

Achim Menges marvels at how Otto managed to extend his methodology, “of trying to find a kind of equilibrium between external boundary conditions and internal force distribution”, towards a kind of construction technology, like the Multihalle in Mannheim, “where the form-finding actually took place on site in a construction process that employed the elasticity of the material to find a particular form: a radical rethinking of what construction and fabrication could be.”

-

Detail of the 2011 research pavilion’s wooden “skeleton plates” made of sheets of plywood 6.5 mm thin. (Photo: courtesy ITKE)

-

Stuttgart today

Since succeeding Otto, Werner Sobek has developed ILEK further, particularly in terms of its multidisciplinarity: its 35-strong team now comprises architects, engineers, aircraft engineers, structural engineers, ceramic engineers and biologists. ILEK is still focused on making buildings lighter, but on energy-related issues and areas such as urban planning too. “We’ve dramatically widened the scope” Sobek says.

Beyond lightweight

Another visionary thinker, also fixated on the lightweight, was Buckminster Fuller who regularly asked architects: “How much does your building weigh?” But now in a new century this question no longer addresses the complexity of the issues involved. Concrete for example, has evolved in quantum leaps: some ultra high strength concretes now have an extraordinary strength-to-weight capacity closer to that of high quality steel or titanium. Werner Sobek now divides lightweight in construction into three main fields: material lightness, structural lightness and a third: “the energetic part”. It is this latter area that has dramatically superseded the levels of the second half of the twentieth century.“Nobody talked about energy then”, says Sobek, “or if they did, it was energy consumption over the lifetime of the building, not embodied energy or grey energy, which means the energy you need for the production and transport of the materials involved. For example in a newly finished residential building, this embodied energy has already added up to between twenty-five and thirty-five times the future annual energy consumption of the building for heating, cooling and cooking etc.” In talking about “lightweight” today, architects and engineers, need to consider not just structure and materials but the whole holistic minimising of embodied energy emissions.

This thinking permeates all the research at ILEK and other institutes at Stuttgart. Research is going on into such things as adding “artificial muscles” with sensors to structures, enabling them to adapt to varying loads and other environmental conditions. Other investigations are into lightweight, multi-layered textile façades capable of “harvesting” and storing energy, and into new forms of superlight concrete structural elements “foamed” inside in places – just like bones. -

![]()

New goals, new roles

So where is engineering and architecture going next at Stuttgart? What can we expect for the future?

Sobek points out that purely practically, with an expanding world population in a time of growing material shortages, the focus has to be on recyclability: “This is a topic I’ve been teaching since 1992, when there was nobody out there talking about recyclability. This puts us in the pole position with worldwide research, because we’ve been doing it for twenty years. That’s why Harvard, MIT, Chicago, Moscow and Singapore universities are knocking at our door asking for co-operations.”

Walz believes strongly there is no point just playing around experimenting if you don’t know where you’re heading: “The problem generally is that the steamboat of conventional architecture chugs stubbornly on, immune to change. Productivity in the building industry hasn’t changed for the last twenty-five years. We build now more or less as we did 100 years ago with just a sprinkling of the digital here and there. Frei Otto indicated new ways, but apart from a few things like rope nets, grid shells and tents, none have had an impact on everyday architecture. What’s missing is a goal. Society has to start defining common goals again. Where do we want to go?”

Menges agrees, seeing the pivotal role of production in the future, facilitating a high level of differentiation – formally less limited and achieving high levels of adaptation – as in nature. This means no beginning or end to a building, but a constant state of growth and adaptation.

“The distinction between the digital and the physical has been eroded with their gradual integration allowing new ways to address how things are made. This will have a profound impact on architecture. Design and process will ultimately converge, meaning buildings will never reach a final stage of conclusion.” I -

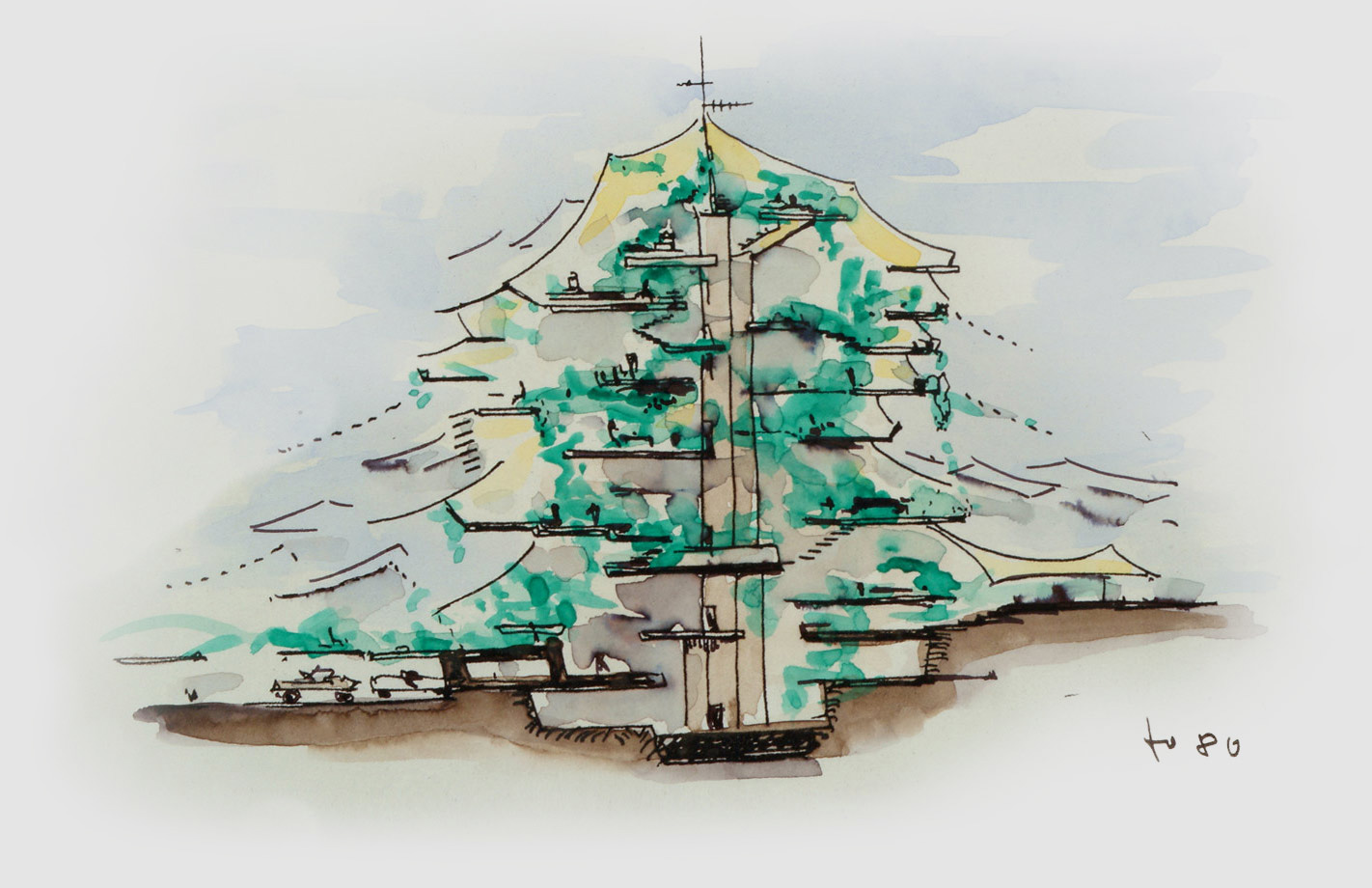

![]()

PaperweightJapanese Pavilion, Expo 2000,

Hanover, Germany

2000 (now demolished)

Shigeru Ban, Frei Otto, Buro Happold![]()

Photo: © Adam Wilson, courtesy Buro Happold

-

When Japanese architect Shigeru Ban asked Frei Otto to collaborate on the design of the Japanese Pavilion for the Hanover Expo 2000, it was with an unusual request: to design a recyclable paper structure reflecting the Expo’s environmental theme. The design they came up with, developed with British engineering firm Buro Happold, used cardboard tubes 12.5 centimetres in diameter and up to 40 metres long, to form a grid shell, whose rippled tunnel-like shape was developed to better withstand lateral loading.

The foundations were primarily formed from boxes of sand rather than concrete, while joints were initially proposed to be taped for flexibility, with a roof covering of a waterproof paper membrane, originally developed for delivery bags. However while paper had been approved as a building material in Japan, unfortunately German building regulations could not approve it as the sole superstructure, and an additional timber inner structure had to be developed, while timber and metal replaced taped joints and a PVC membrane was added over the paper one, because of fire safety concerns.

But at 73.8m long, 25m wide, and 15.9m high, the resulting 3,600 square metre roof structure was still an incredible building when it opened, both structurally and experientially: a lightweight structure with an even lighter footprint.![]() (rgw)

(rgw)![]()

Photo: Hiroyuki Hirai, CC by 2.0

-

![]()

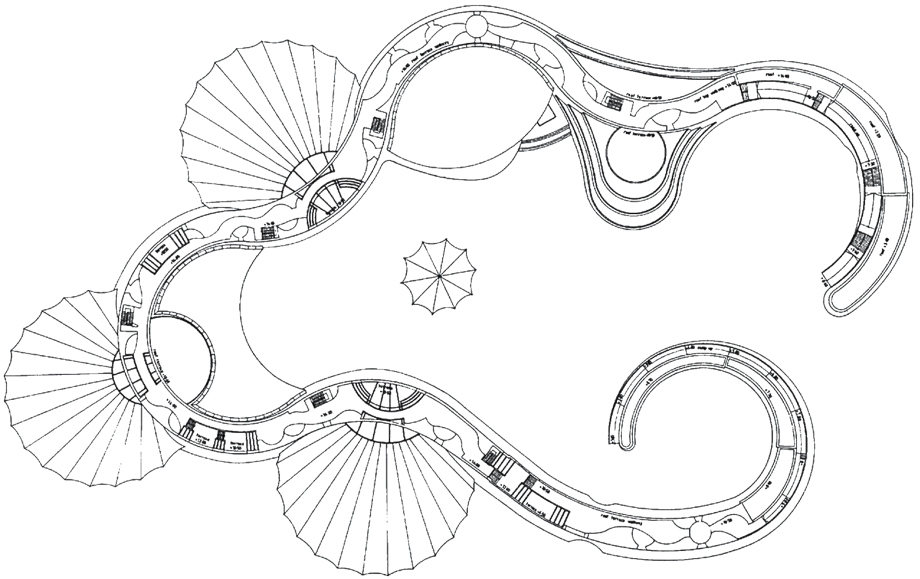

Heart of LightnessDiplomatic Club

Wadi Hadifeh, Saudi Arabia 1985

Omrania Associates, Frei Otto, Buro Happold![]()

Aerial view of the Tuwaiq Palace, formally the Diplomatic Club. (All photos courtesy Aga Khan Trust for Culture)

-

![]()

In 1981 Frei Otto was invited by the Saudi Arabian Government to work with local Saudi architects, Omrania Associates and Buro Happold engineers to design a diplomatic complex in the desert. Sited on a rocky plateau in Wadi Hadifeh, the Diplomatic Club, known today as the Tuwaiq Palace, is an impressive architectural response to the harsh desert climate – merging local architectural heritage with new developments in structural design, some of which emanated from Otto’s Institute for Lightweight Structures.

The building is composed of two main form types. The first is a curvilinear limestone wall surrounding an inner garden. Made from local stone, this thick hollow wall functions as a thermal barrier, protecting the inner vegetation from the severe heat, as well as housing guest rooms and public lounges. The other form type consists of three tent structures spanning out from the surface of the massive wall, charmingly resembling the way desert roses cling onto rocks.

At the centre of the inner courtyard, in a lush oasis garden, lies the “Heart Tent”, an umbrella-like structure, whose glass roof tiles were hand-painted by Bettina Otto, Frei Otto’s daughter. Creating an impression of a second paradise, this open tent serves as a haven for the diplomatic guests and visitors. The palace’s remarkable design earned it the prestigious Aga Khan Architecture Award in 1998. p (sf)

![]()

Interior views of the southern multi-purpose hall and the “Heart Tent”.

-

Ever the tireless inventor, Frei Otto designed vehicles for all kinds of conditions: air, water, snow and road. As early as 1952 he published a design for a motorised sledge. Tracked vehicles already existed, but his sledge was based on a new propulsion system intended to facilitate, with the help of a foldout windmill, manoeuvrability in the Arctic.

Otto also analysed wind power for a revolutionary sailing boat concept: here he proposed sails made from thin plywood, rather than fabric and devised steerable runners in the water for the catamaran-like construction to skate across the water surface. This “superboat” incorporated state-of-the-art aerodynamics – and the forward-thinking it embodied is borne out today by the use of rigid sails now used by the world’s fastest racing boats.

Otto’s “superboat” was followed by a “supercar” in the early 1960s. Commissioned by the Indian National Design Institute, Otto came up with a convertible with a sliding roof, an enormous windscreen and a streamlined front. The interior, however, revealed a roomy family car, fully equipped with camping gear and a refrigerator. In combination with a tent – also designed by Otto – the car could also transform into a mobile home. I (Franziska Stein)

-

![]()

A conversation with Jean-Philippe Vassal

Interview by Georg Vrachliotis

Photography by Jean-Philippe Vassal -

Jean-Philippe Vassal, one half of the French architecture duo Lacaton & Vassal, is a huge Frei Otto fan and particularly influenced by his 1980s “Eco-houses” in Berlin. Architecture Theory Professor Georg Vrachliotis talked to him for uncube about designing open systems in architecture and ensuring maximum freedom for residents.

The work of Frei Otto has typically been analysed in two ways: from an architectural perspective focusing on form finding, and an engineering perspective exploring material, construction and structure. In what way did you first approach Otto’s work?

It was through a small book, Cómo construye la otra mitad (How to build the other half), published in Spain over 20 years ago, part of the series: Fisuras de la cultura contemporánea (Fissures of contemporary culture). Although it was not the first time I’d engaged with Otto’s work, this book was very important for me. In it he speaks of his own experience, particularly the back and forth process in the design and construction of the “Ökohäuser” or “Eco-houses” in Berlin’s Tiergarten. I didn’t know the project before and was fascinated by the way he’d designed the structures. I started to use the project as a major reference for my own office’s work, and also later when teaching classes at the Technical University Berlin. The Ökohäuser were part of the IBA – the Internationale Bauausstellung (International Building Exhibition) Berlin 1984/87. I heard that the relationship between Frei Otto and Paul Kleihues (the director of the IBA at the time) was quite difficult and challenging back then, and that there were a lot of issues concerning site and the experimental nature of the project.

All photos: Jean-Philippe Vassal.

-

![]()

Video: Dreaming of a Treehouse, a documentary about the Ökohäuser. (Video courtesy of Beate Lendt, x!mage).

-

Frei Otto actually planned a similar version of the Ökohäuser for New York’s Central Park in 1959, almost 20 years earlier: the so-called “Baumhäuser”, or Tree Houses. We have a wonderful model of them in the saai archive. Do you know the project?

No, but their structure seems comparable to the Habitat 67 project by Moshe Safdie. At Lacaton & Vassal we took a lot of inspiration from Ökohäuser, particularly when designing the Nantes School of Architecture, completed in 2009. The main concept for that project was to create a structure with huge capacity. That’s the reasoning behind the platforms. With a minimal budget we were able to generate the maximum possible space, more than doubling the project’s usable floor area from around 12,500 to 26,000 square metres.Can you explain more about the platforms?

The platforms are a sort of building system comparable to both Le Corbusier’s 1914 Domino open floor plan and John Habraken’s concepts of “support” and “infill”, as published in his 1962 book Supports, an Alternative to Mass Housing. Herman Hertzberger is also a key influence. Using platforms means first building a very simple three-dimensional structure and then generating the programme. In developing platforms we want to create the spatial conditions and open qualities of a loft, giving inhabitants a meaningful role in the process of adapting the space.

Are such projects comparable to the structures of Yona Friedman? In 1957 to 1958, he and Frei Otto initiated the Groupe d’étude d’architecture mobile (G.E.A.M.) to promote concepts of mobile and adaptable architecture.Of course. The influence of Friedman also plays a central role in our work. His building systems and theory of mobile architecture in particular have affected our own thinking about systems. I actually discussed Otto’s Berlin project with him.

You discussed Frei Otto’s Ökohäuser with Yona Friedman?

Yes. Just like me, Friedman was very interested in Frei Otto’s concept of adaptation. -

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

Nevertheless, he said that he found the Ökohäuser’s structure too small. The residents immediately filled it up, leaving no open free-space remaining. Friedman also said he felt the system didn’t have enough flexibility for its residents. However, I think it’s a really fantastic project, especially given its location in the heart of Berlin, next to the Tiergarten. In fact, I’ve photographically documented every spatial condition and garden of the Ökohäuser, along with the living spaces of the residents. Did you know that Frei Otto didn’t cut down any trees to build the project? I think, in terms of current architectural discourse, this project is a very important one.

Do you still believe in flexibility in architecture?

Yes, I firmly believe in the idea that people should have freedom in their individual living space. No doubt being Greek, you’re familiar with the idea of the Polykatikia housing system in Athens in the 1930s, and later developed in the 1950s and 1960s. I really think there are similarities with our current approach concerning the flexibility of the plan. It’s all about producing open systems!

Frei Otto was not only an innovative architect, but also an intellectual, a radical public thinker who promoted the idea of the minimal in almost all aspects of our built environment. Do you think architects should be more radical today?

Absolutely, especially when it comes to questions of economy. But of course, there are many different ways of interpreting the idea of the minimal: material, structure, construction, budget, building costs, etc. For example, after studying architecture in Bordeaux, I worked as an architect and urban planner in Niger, West Africa from 1980 to 1985. In that time I learned that in the desert everything is about producing shade, using very simple structures and minimal material. So I began analysing the temporary, mobile constructions of nomadic people to better understand the idea of what we later called open systems. I think that to build cost effectively is one of the most crucial responsibilities for architects today.

Structuralist approaches had a great influence on your work. Are you suggesting we should rethink the design strategies of 1960s?

I am certain that the 1960s are still very important for us today. One of the key aims of architecture today is to keep the spirit of that time alive. -

Georg Vrachliotis is Professor for the Theory of Architecture at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), and previously lectured and conducted research at the Institute for History and Theory of Architecture (gta) and the Institute of Technology in Architecture at ETH Zurich from 2005 to 2011. He studied architecture at the Berlin University of the Arts (UdK) and was awarded his PhD at ETH Zurich in 2009. He has since taught at the Universities of Freiburg and Bremen, as well as at the Department of Architecture of the University of California at Berkeley. Since 2014 he has been head of the Archive for Architecture and Engineering in Southwest Germany (saai).

saai.kit.edu

Jean-Phillippe Vassal (*1954) is an architect and one of the two founders, with Anne Lacaton, of the Paris-based practice, Lacaton & Vassal. Born in Casablanca, Morocco, he studied at the Ecole d’Architecture in Bordeaux, where he gained his Diploma in Architecture in 1980. Between 1980 and 1985, he practiced as an architect and town planner in Niger in West Africa, before co-founding Lacaton & Vassal in 1987. The practice won the Grand Prix National d’Architecture Jeune Talent, France in 1999, and has subsequently become well known for their work in the cultural, educational and housing fields, including projects such as: the University of Arts and Social Sciences, Grenoble, (2001); Social housing, Mulhouse, (2005); the Nantes School of Architecture (2009); Social housing, Trignac, Saint-Nazaire, (2010); conversion of the Tour Bois le Prêtre housing block, Paris, (2011), Palais de Tokyo, Contemporary Department, Paris, (Phases 1 & 2, 2002 / 2012); FRAC North, Dunkirk, (2013). Vassal has taught extensively, and since 2012 has been Professor at the University of the Arts (UdK) in Berlin.

![]()

Sketch for a treehouse, by Frei Otto. (Image: © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn)

-

![]()

Featherweight

Hellabrun Zoo Aviary

Munich,Germany 1980

Jörg Gribi, Frei Otto, Buro Happold![]()

-

![]()

![]()

The gracefully draped steel net reaches a height of 18 metres at its tallest point (Photo: © Atelier Frei Otto, Warmbronn; aerial view: courtesy Hellabrun Zoo)

One of the buildings Otto was most proud of was his Hellabrun Zoo aviary, that he designed in the late 1970s in collaboration with architect Jörg Gribl and engineer Ted Happold. Something of a “little sister” to Otto’s other big Munich project, the Olympic Stadium, the aviary is also a fair few tonnes lighter as well.

The diaphanous sense of space it conveys, spanning part of a wooded landscape, is strongly reminiscent of spider webs. Indeed with this design, Otto really showed his influences from nature to their full extent. Completed in 1980, the aviary is a fine successor to another great example of tensile avian innovation: Cedric Price, Frank Newby and Anthony Armstrong-Jones’ 1964 Snowdon Aviary at London Zoo. The huge steel mesh enclosure covers some 5,000 square metres in area and reaches up to 22 metres in height, allowing its avian residents considerable freedom to stretch their wings.

Originally it was anticipated that the stainless steel mesh canopy would have a working life of around twenty years, yet thirty-five years on it still functions effectively. Remarking upon the structure’s enduring success recently, the Zoo’s Chairwoman Christine Strobl found it in fine feather, describing the enclosure as “virtually maintenance free”.

![]() (fs)

(fs)Previous page: The view from inside the seemingly gravity-defying structure of Hellabrun’s Aviary.

(Photo: © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn). -

When Frei Otto, a visiting professor at Washington University in 1958, met Buckminster Fuller, who was a teaching professor there, for the first time, their encounter began with a heated conversation about “wide-span constructions”. An unusually intense engagement for newly acquainted colleagues perhaps, but these masters of material reduction and minimal construction, already familiar with each other’s work, knew no other way. Sharing a mutual fascination with nature and biological form, the two genius designers had both dedicated their lives to realising lightweight structures embodying the notion of “building more with less”, each in their own distinctive single-minded manner. Later on, when Frei Otto moved back to Germany, they would meet again, this time at the Institute for Lightweight Structures (IL), a worthwhile journey for Fuller as the IL was were all the magic was happening at the time. Think tank, design laboratory, publishing office, lecture hall and community of like minds, it was the perfect venue for the two ex-colleagues to meet and take up from where they last left off. I (sf)

Richard Buckminster Fuller, Milan X Triennale paperboard domes before assembly in 1954. (Source: aaa-laboratory.blogspot.de)

Photo: © ILEK, Stuttgart

-

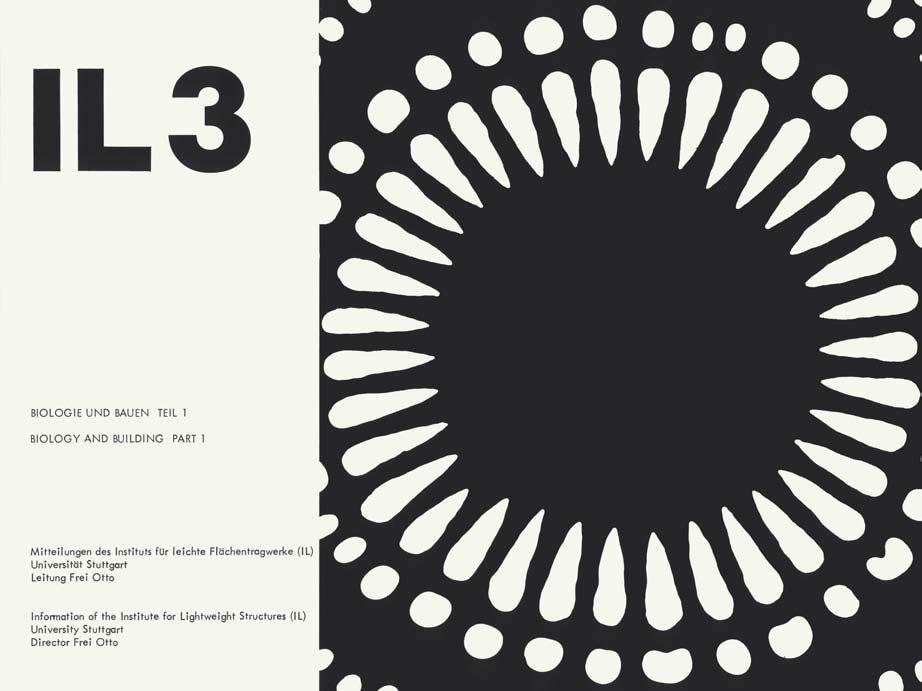

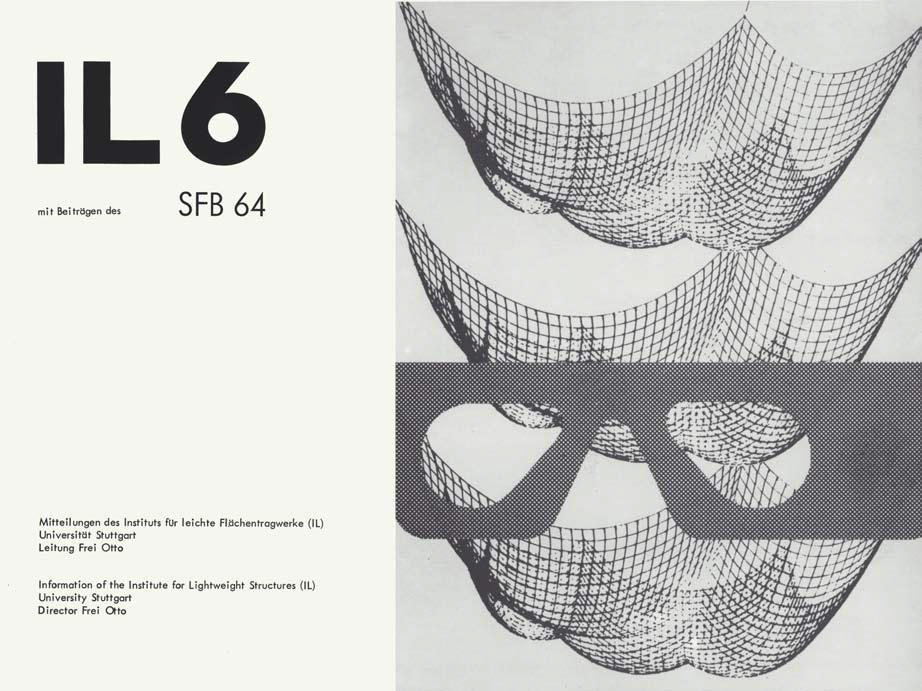

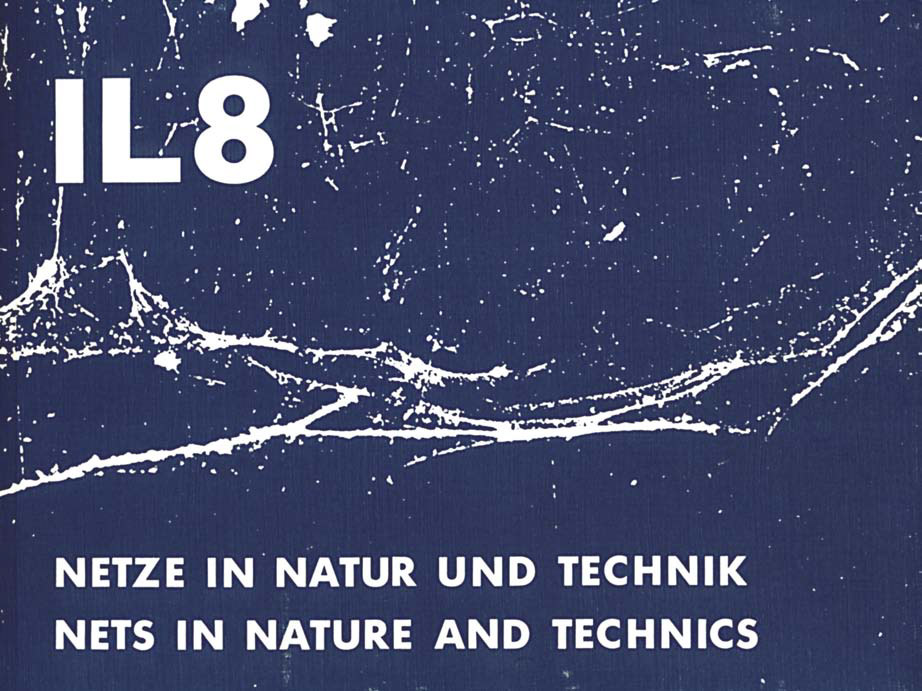

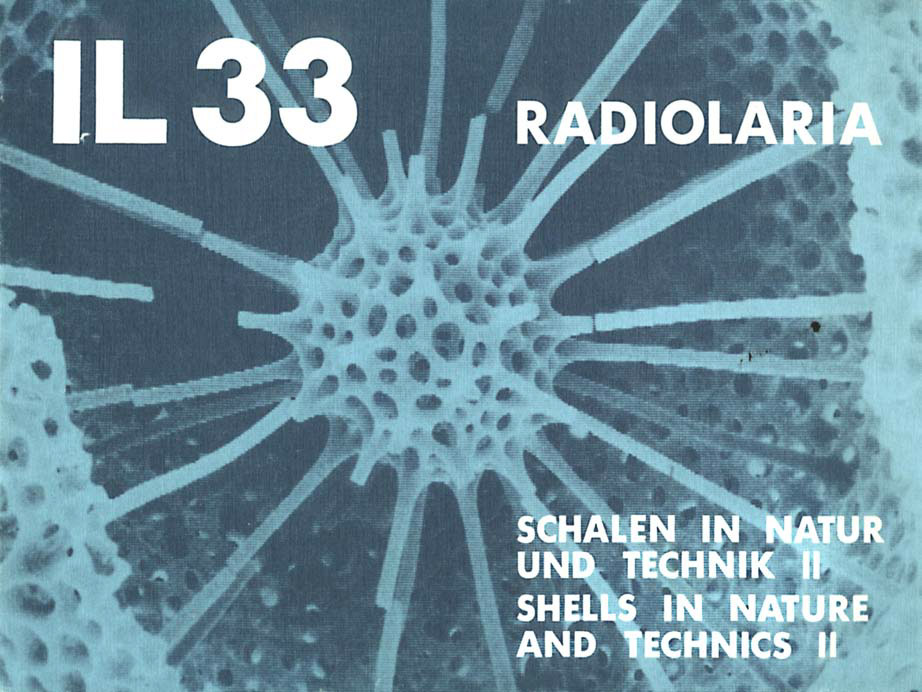

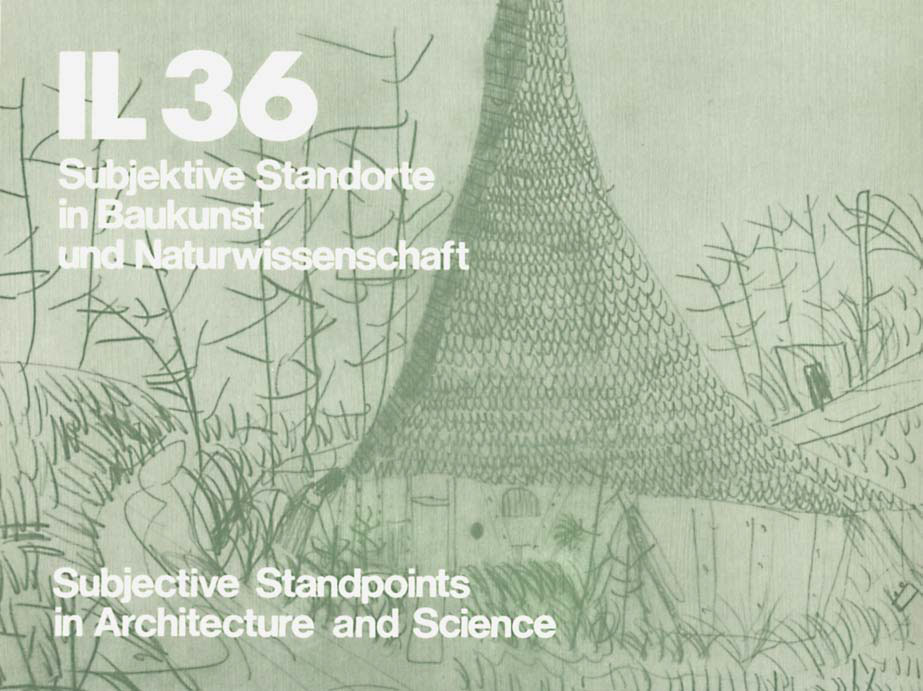

Reflections of an enquiring mind

So prolific a thinker was Frei Otto that he took to sharing his ideas and research with colleagues in published form: the IL Bulletin. uncube presents a selection from the archives, each documentating his extraordinary output of drawings and models. -

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

All images: © ILEK, Stuttgart

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

Inspired by the diversity of forms found in nature, Frei Otto analysed everything from cell structures, bones, tree trunks and spider’s webs to whirlpools, soap bubbles, termite hills and bird’s nests. To measure them he developed instruments for studying the self-organising processes of nature, tables to determine force vectors and apparatuses for determining forms of pneumatic construction. These models – a world away from architectural models in the classical sense – function less as static objects and more as dynamic ones: experiments in the processes of the environment. Thus they embody an “operative aesthetic” that oscillates between the precision of scientific instruments and imaginative artistic tools.

These experimental aesthetics gave rise to their own visual language which can be seen in the photographs, graphics, diagrammes and drawings that appeared in the forty-one IL Bulletins that Frei Otto published at his Institute for Lightweight Structures (IL) at the University of Stuttgart, between 1969 and 1995. These publications presented research projects or addressed specific issues around construction material and form. Each issue was devoted to a particular theme – such as: Minimal Nets (IL 1, 1969), City in the Arctic (IL 2, 1971), Shadow in the Desert (IL 7, 1972), Forming Bubbles (IL 18, 1988) or Bamboo (IL 31, 1986) – reflecting the huge range of Frei Otto’s research and interests. I (Georg Vrachliotis)![]()

![]()

-

When Alvar Aalto presented a brand new technique for manufacturing his timber furniture out of “wooden macaroni” in Paris in 1950, Frei Otto was fascinated. This demonstration that it was technically feasible to produce a wooden form that looked as if it had grown naturally, led him to his own ruminations on similar techniques. The following year, in an article for Bauwelt, Otto mused upon the Finnish architect’s mysterious technique, for Aalto never revealed his secret: “Aalto remains silent. No one knows how he does it. He has not revealed anything even to his friend and countryman Eero Saarinen, nor does the third of that bunch, Charles Eames, know how.”

Without access to a recipe, Otto nevertheless suggested some of his own ideas on the use of revolutionary wood compounds. A number of years later he published his designs for beds and chairs in the same magazine, showing examples of cloth and wood constructions adhering to the principles of his large-scale tensile structures. The designs were intended to be waterproof and appropriate for use outdoors, enabling the expansion of living space into the garden. The only object produced in greater numbers however was the Montreal Chair of 1967, designed for Otto’s German pavilion at the World’s Fair that same year and developed according to similar principles. I (Franziska Stein)

A prototype of the stacking chair designed by Frei Otto for the German Pavilion, Expo 67. (Source: www.architonic.com)

Some of Otto’s sketches that originally appeared in “Neue Bauwelt”, issue 20, 1951.

-

![]()

Flyweight

West German Pavilion, Expo 67

Montreal, Canada 1967

Frei Otto, Rolf Gutbrod, Fritz Leonhardt et al.![]()

![]()

The West German Pavilion at Expo 67, Montreal. (Photo: © Atelier Frei Otto Warmbronn) Film (no audio): footage of the development and construction of the Pavilion’s cable net structure. (Film produced by IL‚ 1981, courtesy ILEK, Stuttgart)

-

“Germany took six weeks to put up this tent, 1,200 years to put on the show inside. Come to Montreal and take a look. It’s some tent,” announces a poster for Expo 67 emblazoned with an image of the West German that pavilion Frei Otto designed for the event. A similar logic applied to the structure itself – the principles underpinning the tent concept had been years in the making; developed by Otto ever since he completed his doctorate in 1954, entitled: The Suspended Roof, Form and Structure.

Producing a truly iconic pavilion at Montreal was no small feat given the fact that neighbours at the site included Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome representing the United States and Moshe Safdie’s housing complex, Habitat 67. But Otto’s design eschewed the World’s Fair archetypes of the box and the sphere; instead it was a “roofscape” of such apparent lightness that it seemed on the point of taking flight.

Produced in collaboration with Otto’s friend Rolf Gutbrod, the design was intended to represent Germany’s rich heritage of industry and engineering. In fact it advanced that heritage several steps further. Making use of the “dynamic relaxation” numerical method to determine the canopy’s form, the structure’s translucent plastic skin was supported by eight steel masts and covered an area of 8,000 square metres. Underneath all that pre-stressed cable and textile membrane, visitors could view the work table used by Otto Hahn when he discovered nuclear fission in 1938, a replica of Guttenberg’s printing press and, in a nice nod to that other seminal German Expo structure, a model of Mies van der Rohe’s pavilion for the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition.

Post-Expo the tent was due to be dismantled and shipped to Germany. However, the nation it represented never got to enjoy one of the world’s first truly passive solar buildings: the pavilion passed into the ownership of the City of Montreal, who would eventually demolish the structure in 1973 to make way for – guess what – the 1976 Olympic Games. I (fs)![]()

Expo 67 visitors inside the West German Pavilion. (Photo: © Burkhardt‚ courtesy of Atelier Frei Otto, Warmbronn)

-

![]()

Focus on Frei Otto by his colleagues and peers

By Stephan Becker

![]()

Great architects are not necessarily great teachers, nor great advocates for their ideas. So what was so different about Frei Otto that his influence can be traced in the designs of the world’s most renowned architects? For him, designing wasn’t about fancy uniqueness or a sensational display of his skills, but about finding an ideal solution to a fundamental, often existential problem. He was like a researcher without the need or desire to do follow all his research through to conclusion, but with the satisfaction of seeing his seminal ideas spreading through other’s work. His dedication and work drew an illustrious collection of admirers such as Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid and Renzo Piano. Frei Otto was someone to be inspired by, not to compete with. This explains the relationship between his comparably small built oeuvre and the great number of projects by others that pick up on his ideas. He was equally influential in spatial, technological and conceptual areas, as some of his famous friends tell us here in their own words.

-

“Like Luis Kahn asked the brick, Frei Otto kept asking the air what it wanted to become. He kept thinking about how to envelop ‘air’ with the minimum of ‘material’ and power. His achievements, rather than just being his ‘works’, have become the grammar of structural design, unnoticed by many, and we are only now realising that we unconsciously base our designs on his grammar.”

At first sight, in relation to Frei Otto’s projects, some of Shigeru Ban’s designs seem to be the work of an ardent fan. But a closer look reveals his own achievement: not only the adaption of Otto’s original ideas for new materials and construction techniques, but also the marriage of different spatial paradigms. The tent and the box, together forming a new typology that allows for different uses and programmes.

Shigeru Ban. (Photo: Flickr/Valerij Ledenev, CC BY-SA 2.0)

![]()

Centre Pompidou-Metz, 2010, Paris, France. (Photo: Flickr/Martial Geoffroy, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

»Like Luis Kahn asked the brick, Frei Otto kept asking the air what it wanted to become. His achievements have become the grammar of structural design.«

Shigeru Ban

-

Even though Renzo Piano is twelve years Frei Otto’s junior, their work has to be seen more as a parallel and intertwined development than a simple following. Interestingly, their shared interest in lightness has usually led Piano to very different solutions. This is especially apparent with his projects sited in historic surroundings, where he combines constructonal efficiency with a strong sculptural presence.

Renzo Piano. (Photo © Ed Alcock)

»Frei Otto has been one of the most seminal people on my route to architecture. Exploring the movement of forces within the structure to make it visible. Celebrating lightness. And fighting against gravity.«

Renzo Piano

Biosphere, 2001, Genoa Porto Antico, Italy. (Photo: Flickr/Basilicataintir, CC BY-NC 2.0)

![]()

-

“The fluidity of Frei Otto’s work is as uplifting as it was profoundly inventive – a persuasive manifesto of nature’s logic and unity, demonstrating how architectural design and engineering can emulate nature’s morphogenesis. The more our own design research evolves, the more we learn to appreciate his pioneering works. We first met in Germany early in my career and he became a dear friend.”

Particularly in her early years, the decisively modern architecture of Frei Otto didn’t seem the most likely inspiration for Zaha Hadid – who was a major proponent of deconstructivism back then. On the other hand, her interest in Otto’s work is not just limited to technological aspects, but to the spatial effects it created. A tent, for her, is not just an efficient way to span large areas, but an actual piece of architecture to be experienced, a piece of architecture epitomising the dynamics of life. This wasn’t always one of Otto’s main concerns, perhaps, but it quite often accompanied the public perception of his projects. With very different concepts and materials, Hadid takes this approach to an entirely new level.

Zaha Hadid. (Photo © Brigitte Lacombe, courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects)

![]()

» The fluidity of Frei Otto’s work is as uplifting as it was profoundly inventive – a persuasive manifesto of nature’s logic and unity, demonstrating how architectural design and engineering can emulate nature’s morphogenesis. «

Zaha Hadid

London Aquatics Centre, 2011, UK. (Photo © Hufton + Crow, courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects)

-

“Frei Otto showed us that architecture need not be burdened by the weight of its own traditions, but could instead be free to express itself through simple but innovative sculptural forms – his was an architecture inspired by lightness. This sense of weightlessness, and of an architecture unbound by convention, was carried over into Frei’s working relationships. For me, he reinforced the point that architecture is a fundamentally collaborative exercise. His structures altered the nature of architectural form in the twentieth century and his environmentalism, intelligence and foresight have established the defining architectural mentality for the twenty-first.”

It is very easy to find formal aspects in Norman Foster’s work that bear reference to Frei Otto’s projects. But more importantly, Otto’s unique combination of technology and nature showed Foster how to move on with modern architecture amidst all the post-modern dissidence. It is not in any particular design but in Foster’s fundamental approach to practice, where Otto’s thinking becomes most apparent.Norman Foster. (Photo: Flickr/Fabian Mohr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

![]()

Buenos Aires Ciudad Casa de Gobierno, 2010, Argentina. (Photo © Foster + Partners)

»His structures altered the nature of architectural form in the twentieth century and his environmentalism, intelligence and foresight have established the defining architectural mentality for the twenty-first.«

Norman Foster

-

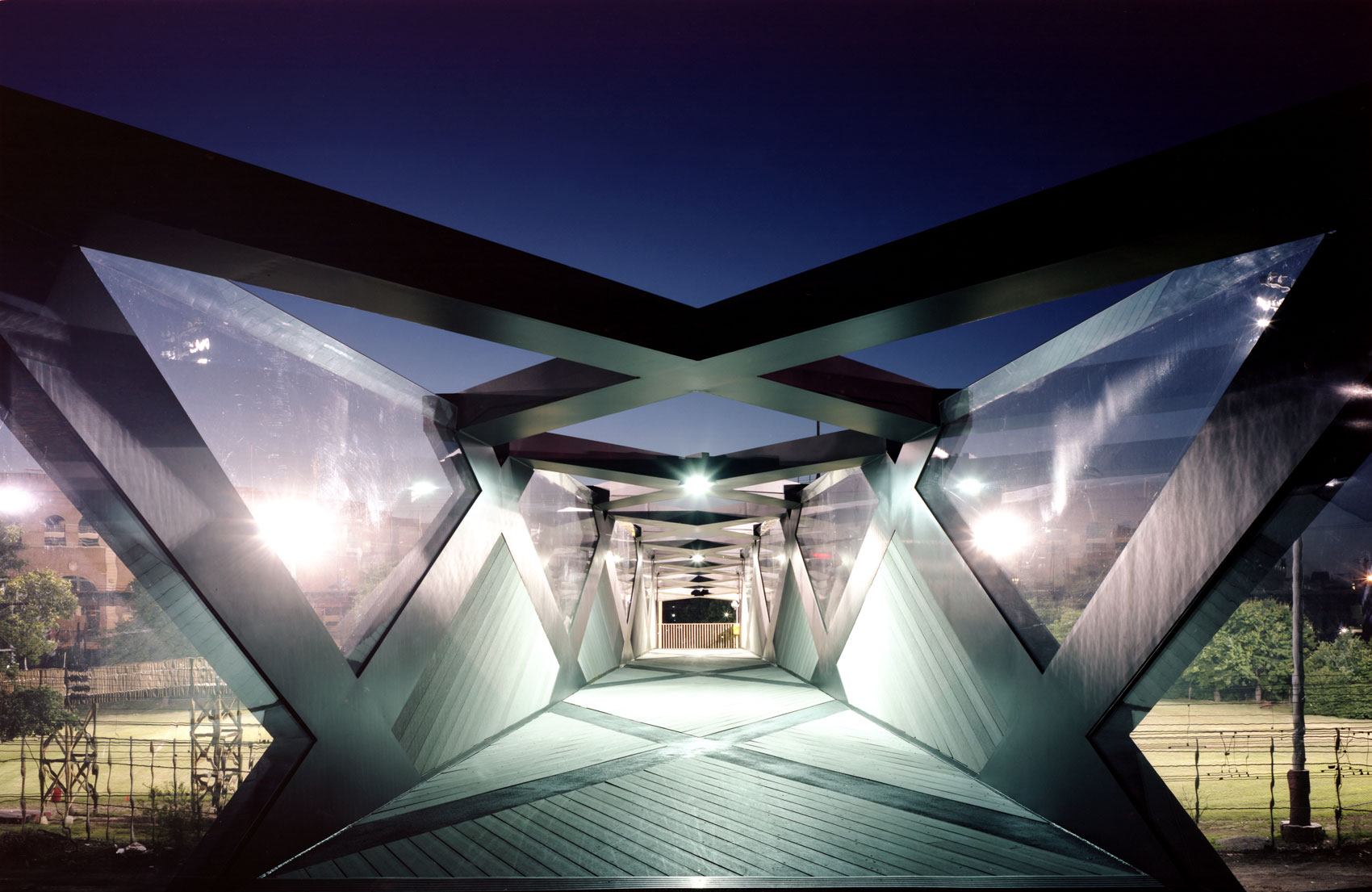

Wanting to build often means having to compromise, and that’s perhaps one of the reasons why Frei Otto so decidedly focused on research and collaboration. It allowed him to work only on pioneering projects, a rare privilege he shared with the architect and engineer Cecil Balmond (born 1943). Despite teaming up with some of the world’s most renowned practitioners, for Balmond, as it was for Otto, the true field for experimentation is his individual work. In his studio or at the university, Balmond mirrors Otto’s fundamental curiosity across every aspect of practice.

Cecil Balmond. (Photo: Olivier Hess)

»When I first saw Frei’s work I felt the rush of discovery, the images opened up and revealed minimum surface, optimisation and grace of form – he was a one-off.«

Cecil Balmond

Weave Bridge, 2009, University of Pennsylvania, USA. (Photo © Alex Fradkin)

![]()

-

Membrane structures have a very particular aesthetic, simply because they follow the fundamental laws of physics. For Michael Hopkins, on the other hand, this isn’t something to just accept. Showing a similar spirit to Frei Otto’s lifelong search for new approaches, his complex systems redefine what can be done with flexible materials. Not just tent-like structures, but any architectural form needed for a specific use.

Michael Hopkins. (Photo © Tom Miller, courtesy Hopkins Architects)

![]()

Schlumberger Cambridge Research Centre, 1992, UK. (Photo © Dave Bower)

»For me, Frei Otto was the grandfather of all our membrane structures. We discovered that membranes would not only enclose space and transfer light, but would also transfer load and stress. We owe him a great debt.«

Michael Hopkins

-

![]()

Moving MountainsOlympic Stadium

Munich, Germany 1968 –1972

Frei Otto, Günter Behnisch![]()

-

The view from the stands at the Olympic Stadium, Munich. (Photo: Flickr/Gerry Smith, CC by 2.0).

If one project propelled the work of Frei Otto into worldwide consciousness, it was the spectacularly sinuous silhouette of the roof he designed with architect Günter Behnisch for the stadium of the 1972 Munich Olympics: a pinnacle of achievement for both architects.

Formed of steel cables and acrylic glass panels, and suspended from pylons up to 80 metres high, this sweeping asymmetrical tensile structure covers a massive area of 74,800 square metres, its peaks and troughs intended to echo the Alps, just an hour’s drive away.

Designed to deliberately contrast with the heavy – literal and historical – load of the 1936 Berlin Olympics, which with its stone-built stadium had acted as a massive podium for Nazi propaganda, the roof was designed to symbolise the new open democratic – and technologically innovative – spirit of West Germany, for what were dubbed “Die Heiteren Spiele”; “the Cheerful Games”.

The Stadium was for many years after the close of the Games used primarily for football, serving as the home ground for both FC Bayern München and TSV 1860 München until the Allianz Arena opened in 2005. Today, with its capacity of 69,000 (reduced from the original 80,000), it is used for everything from papal masses to pop concerts.

Despite the memory of the Cheerful Games, being darkened by the “Munich Massacre”, when Palestinian terrorists kidnapped and killed eleven Israeli athletes, the roof still rides high as a symbol of post-war optimism and of Frei Otto’s genius. I (rgw)![]()

-

“Pneus are ugly”, Philip Johnson reportedly exclaimed when Frei Otto presented him with his pneumatic experiments. A “pneu” is an elastic surface encasing a fluid medium that can both enable growth and accommodate changing forces and stresses through its movement. The word pneu can be applied to the technical (rubber tyres) as well as the natural (biological cells).

Pneumatic structures were one of the key areas of Otto’s research into the creation of forms drawn from nature. His experiments are primarily documented in photographs that appeared in IL 12 Convertible Pneus, published in 1975, depicting entire landscapes made up of plaster models that form contours and cast shadows; wire cables, cutting into elastic surfaces and tubes, rising up and collapsing down.

The master investigator was not unaware of the sensuous aspect of pneumatic structures and published his thoughts in 1985 in the short essay Sinnliche Architektur (Sensual Architecture). The text is a call for more expressive forms in architecture which move and, when possible‚ arouse the viewer. Philip Johnson later began experimenting with pneumatics himself, to which Otto commented: “From extreme ugliness a path leads via the erotic to the aesthetic and back again”. I (Franziska Stein)

“Urpneu air fish” model (Photo: © DAM and Frei Otto)

-

![]()

Mies student and Otto disciple Conrad Roland

By Oliver Elser

-

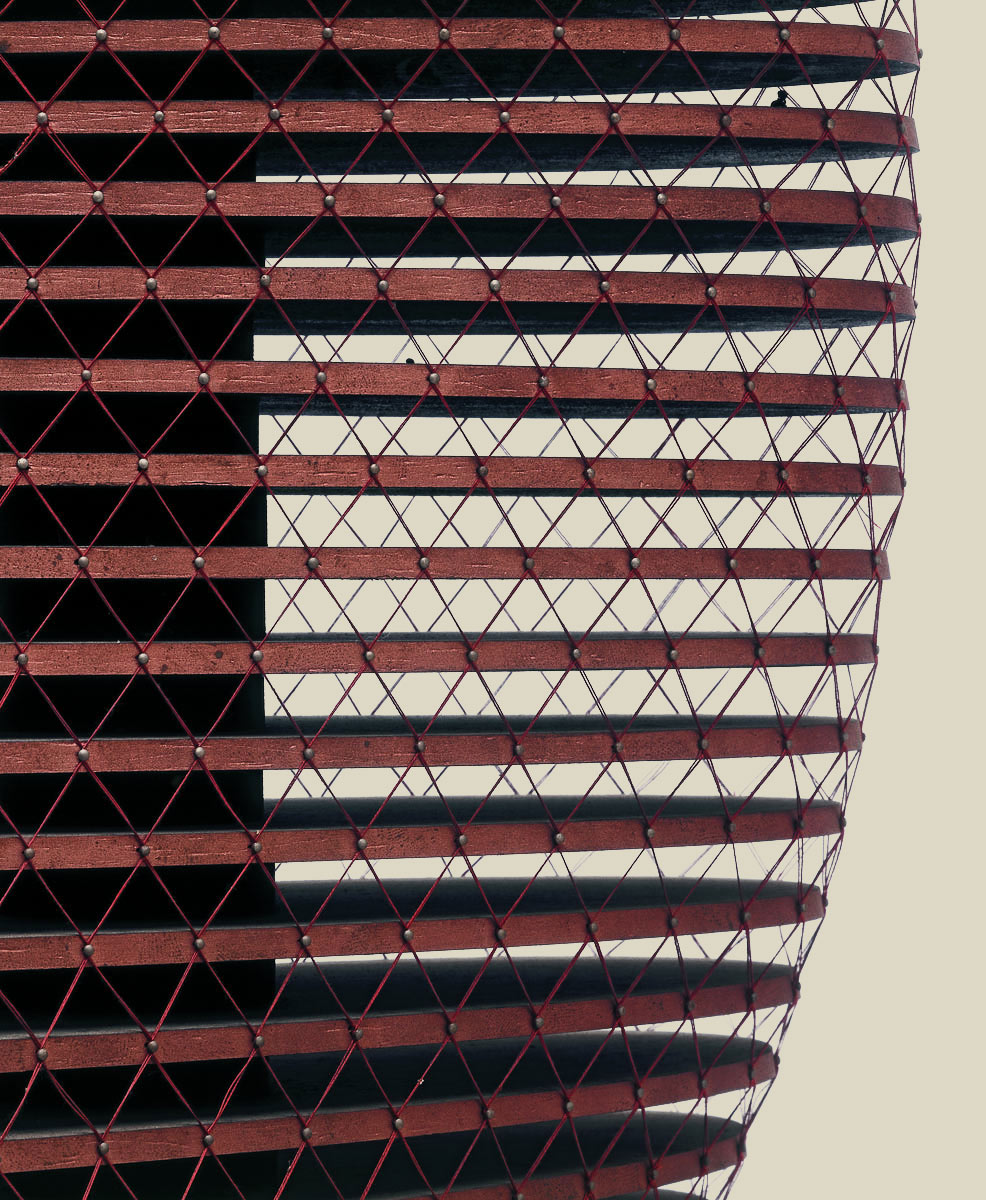

Previous page: Conrad Roland’s 1964 sketch for an exhibition hall with floating platforms. This page: Roland’s “Giant Spacenet” put to the test in Peiting swimming pool, Bavaria, 1975;

Roland’s unbuilt Abu Dhabi stadium design, a collaboration with Jörn-Peter Schmidt-Thomsen, c.1977. (Drawing and all photos courtesy Conrad Roland).The 81-year-old architect Conrad Roland, famous for his Spacenet play structures, has lived in Hawaii for the past 27 years. But before that, his eventful life took him from his birthplace in Munich to Chicago, Berlin and Tahiti. Back in the 1950s, Roland studied at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in Chicago and then worked for Mies van der Rohe before moving to Berlin to work for a while with Frei Otto. He is perhaps the only architect equally at home in the contrasting worlds of Mies and Frei. Oliver Elser talked to him about his life’s journey.

![]()

![]()

-

Otto wasn’t the only one to experiment with the idea of a tensile-structure stadium: a model of the Roland’s 1960s Abu Dhabi stadium project.

-

It is after midnight in Holualoa when the phone rings, but Conrad Roland is wide awake: “The night owl here!” he replies. Our conversation begins with me asking him how he got from the prestigious IIT in Chicago to the office of a, then unknown, architect in Berlin. “The path from Mies to Frei was very short”, he replies, “physically, only about 20 feet”.

It all started in the Institute’s famous Crown Hall, where Roland was a graduate student under professors (and former Bauhaus colleagues) Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig Hilberseimer, and Walter Peterhans. There he worked on his masters thesis between 1958 and 1959.

“Crown Hall is a large open space with only three closed-off spaces inside, called ‘cores’, which were used and abused for storage of old models and all kinds of bits and pieces”, explains Roland. “There I found a broken section of a space frame model made of toothpicks, a leftover from one of Konrad Wachsmann’s students. I became very curious and it inspired me to use a similar three-dimensional filigree lightweight structure for the wide-span roof of my thesis project for ‘An Arts Centre’ in 1959”. At the time, Roland was not yet aware of the Mero roofs built at the Interbau exhibition in Berlin in 1957, which bore membrane structures designed by the young Frei Otto. “Another trip to the Crown Hall core, perhaps looking for some model building material, resulted in a discovery that two years later changed the course of my life as a young architect”. Here Roland found one of Frei Otto’s IL bulletins, dating from 1958, entitled Mitteilung der Entwicklungsstätte für den Leichtbau Nr. 3, Eingangsbogen BUGA Köln, 1957 (Publication from the Development Centre for Lightweight Construction No. 3, Entrance Arch, BUGA [Federal Horticultural Exhibition], Cologne 1957) and was “fascinated by the totally new structure, form, and most dynamic character” of the lightweight fabric membrane it documented. After working in Mies van der Rohe’s office from 1958-61, Roland returned to Germany and headed straight to Berlin. “Needless to say, one of my first excursions there was a long bus ride to Zehlendorf to see Frei Otto at his Entwicklungsstätte für den Leichtbau (Development Centre for Lightweight Construction). It was a most inspiring meeting… with a genius! He handed me a folder with hundreds of sketches for suspended buildings using mostly cable construction. He said: ‘If you are interested, take it with you and make something of it. I am too busy with other things.’” Roland took the folder, wrote some explanatory texts to go with the material and added a few sketches of his own before publishing it as Mitteilung Nr. 8, Mehrgeschossige zugbeanspruchte Konstruktionen (Publication No. 8, Multilevel Tensile Constructions) in 1962. -

That marked the beginning of Conrad Roland’s close relationship with Frei Otto and tensile structures. However, a brief stint in Frei Otto’s office working on actual projects did not turn out too well: “because I inevitably turned out to be a ‘Mies perfectionist’, which collided at certain points with Otto’s somewhat less-than-perfect architectural detailing. We parted in peace after a few weeks, but with my enthusiasm unbroken.” In 1964 Roland began working on the first book to document the already amazing body of innovative work by Otto called: Frei Otto – Spannweiten (Frei Otto – Tension Structures) which he modestly called simply a “report”.

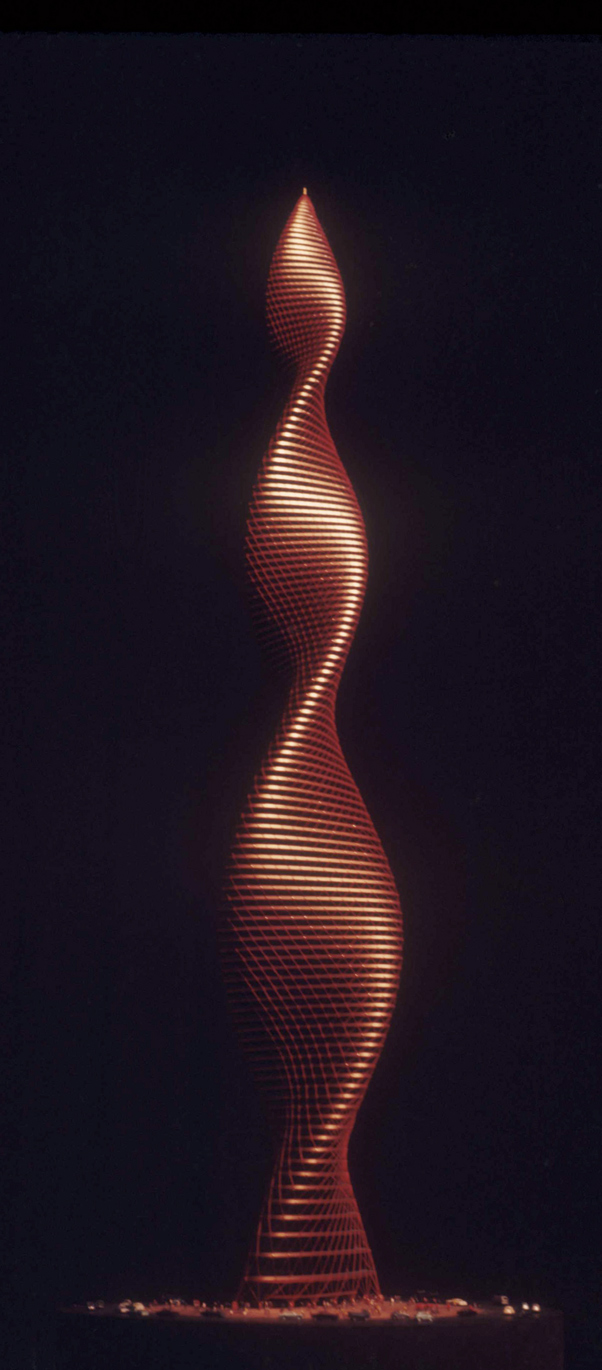

Parallel to his work on the Frei Otto book, he developed countless designs for his own tensile structures. Several skyscrapers, a community centre, apartment buildings and a studio tower. They are poetic, playful, and revolutionary, all at the same time. The most fantastic and consistently logical design he created is his “Spiral Skyscraper”, a 120-storey suspended building reaching 440 metres high, which is one of the most original, visionary skyscraper designs of the 20th century. But it was never built. In 1970, Conrad Roland began designing so-called “Play Spacenets” – three-dimensional tensile climbing nets made of rope and suspended from masts – that became a global bestseller. His company Corocord went on to produce thousands of Spacenets for playgrounds and schoolyards and today exports its products to more than 50 countries.But after 15 years, Roland says, he got bored. So he sold the company to a young Greek architect and left Germany. First for Hawaii, followed by Tahiti, and then back to Hawaii. It is here that he finally decided to build his own house with a four-mast canopy roof design that he’d carried around with him for years. But somehow the house never happened. “It’s the tragicomedy of my life,” he tells me.

![]()

This 120-storey, 440 metre high “Spiral Skyscraper” was proposed by Conrad Roland in 1964.

![]()

-

Oliver Elser is an architecture critic and a curator at the German Architecture Museum (DAM) in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany.

On the plot of land that he originally purchased for building his house, 300 metres above sea level with stunning views over the Pacific, he is now planting bananas and citrus fruits instead. And he marvels about how often spiral skyscrapers have been popping up on the internet during the last few years. But unlike the formal madness of the twisted creations designed for Malmö, Dubai or Toronto, the form of Roland’s design developed purely out of its construction. He quotes his teacher Mies: “We make architecture with the structure alone.” It’s a sentence that could have been uttered by Frei Otto as well. I

Roland’s proposal for a giant cubic space-frame in Berlin‚ filled with residential cells, 1967.

-

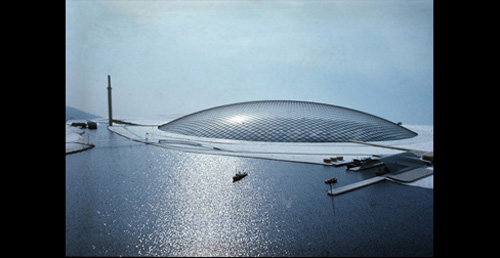

By today’s standards, colonising a portion of the Arctic by encasing a city with its very own atomic power plant – under a PVC dome with a free span of two kilometres – might not sound like the most reasonable of urban planning proposals. But in 1971 it was the future. That year, responding to a commission by a Hoechst AG, a German chemical manufacturing company, Frei Otto and Ewald Bubner at Atelier Warmbronn, together with Kenzo Tange and Ove Arup developed the Arctic City study.

Formulating the proposal’s technical and construction requirements in extensive detail, the designers considered everything from the heating of the artificial atmosphere to the cooling of the power plant’s water systems, as well as analyses of the structure’s capacity to withstand extreme winds and heavy snow loads. It was actually built in April 1971 – albeit rather smaller and within the rather warmer climes of Germany – as a still huge 1:2000 scale model. Spanned across by PVC, foil and fishnet and sited within an Arctic landscape made from foam and Plexiglas, the model even utilises a blower system to produce the appropriate internal pressure.

Drawing upon the utopian ideals of Paul Sheerbart, Hans Scharoun, Bruno Taut et al, Otto, along with Buckminster Fuller, was an enthusiastic developer of light climate hulls, believing at the time that there would be roofed cities in the Arctic by the end of the twentieth century. I (Franzsika Stein)

Photo: Fritz Dressler

Sketch for an Arctic environment by Frei Otto. (Image: © ILEK, Stuttgart)

-

![]()

-

Commune Revisited

Issue No. 34:

May 28th 2015

“A Natural Order: Rita, Cora, aiming” (Photo: Lucas Foglia)

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Less is a bore.«

Robert Venturi

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages