In uncube issue no. 42: Walk The Line we pay homage to the practice of drawing and its role in the representation of place and space. Drifting into the world of psychogeography we found the work of Larissa Fassler, whose consciously subjective depictions of urban space are so extensive, thorough and just plain stunning that we decided to give them a little more space for you to enjoy. Here we show the full range of her documentation of Berlin’s Kotbusser Tor where, as Fiona Shipwright explains, Fassler’s technique thrives on the everyday dynamism surrounding this most unique roundabout.

“The map is not the territory,” wrote scientist and philosopher Alfred Korzybski in 1931. Korzybski was making a point about semantics but the question of cartographic uncertainty still stands: what are the implications of confining a cityscape within the 2D margins of a map?

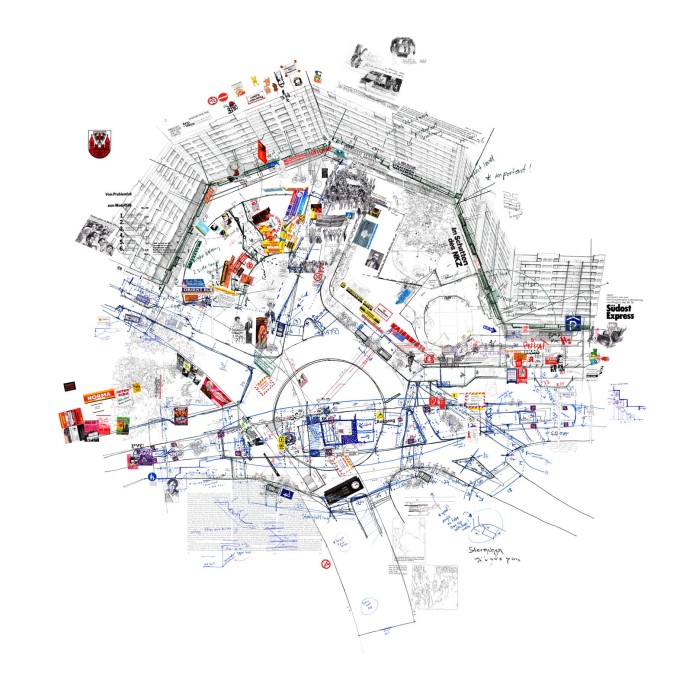

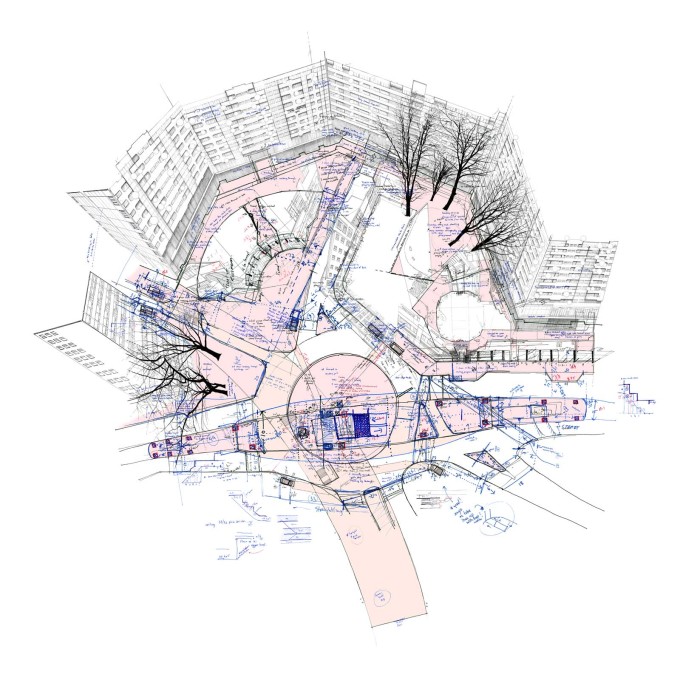

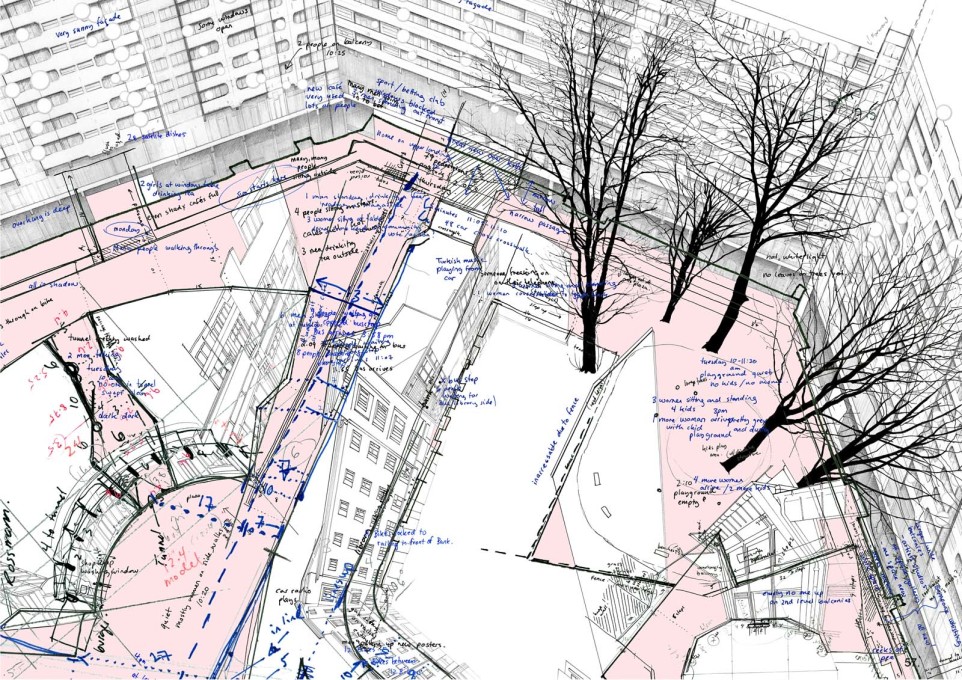

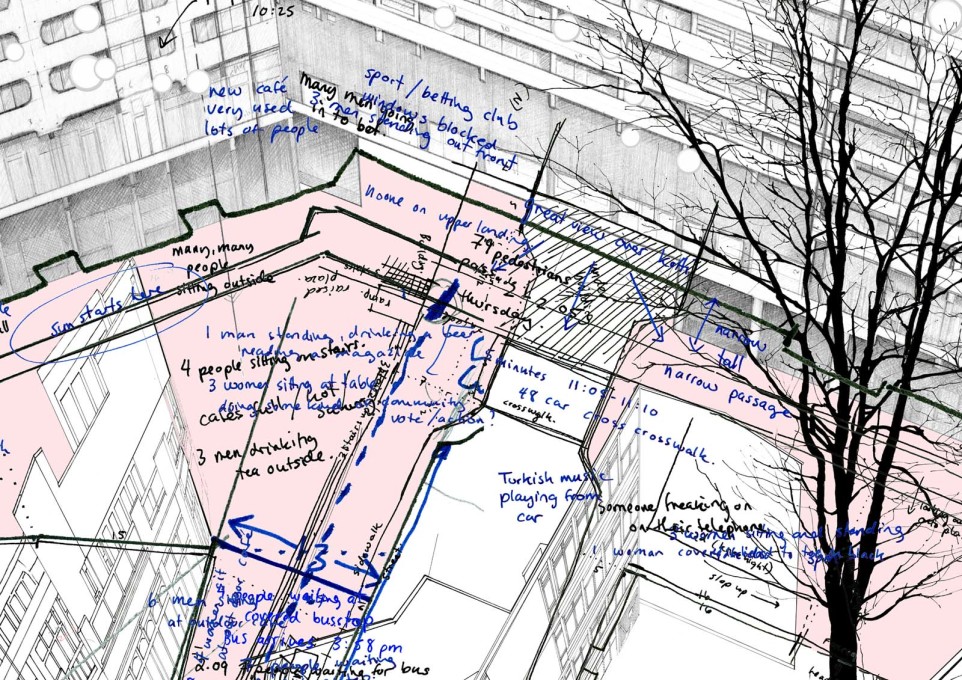

In her use of mapping as a tool for documentation, Canadian/French artist Larissa Fassler deals not just with the geography of space but also the ethnography of place. Spending days at a time sketching and writing on site, Fassler traces by hand all that she sees, superimposing these temporal notations onto paper maps complete with axonometric drawings of the architecture found there.

The work brings to mind the approach of French anthropologist Marc Augé in developing his theories of “non-places” and in particular his own ethnographical investigation of the Paris metro published as a book entitled Un ethnologue dans le métro (1986). In seeking to understand the city of Paris, Augé chose to focus on the infrastructures (both social and built) that lie below the city, the spaces and activities that are often out of sight and mind (for tourists and architects alike). Fassler’s work operates in a similar fashion and in her documenting of Berlin, the sites she has chosen are notable for the fact they have all been contested in one way or another.

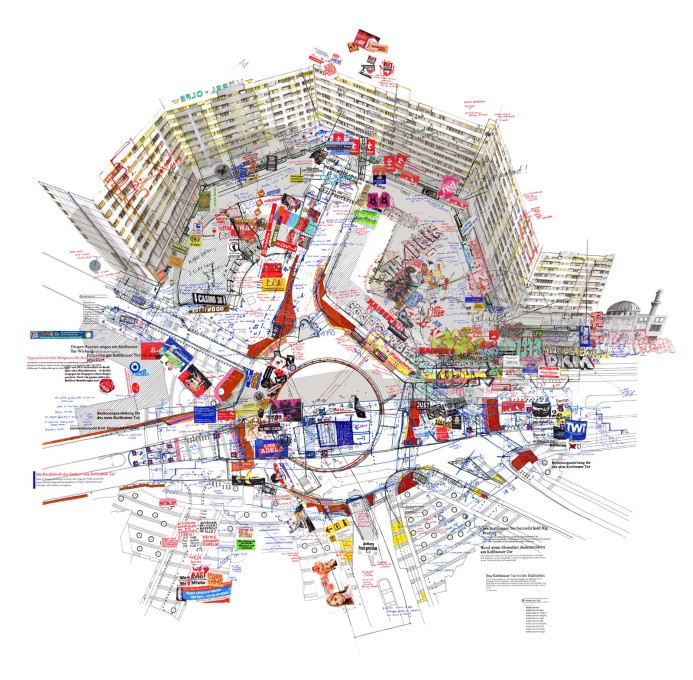

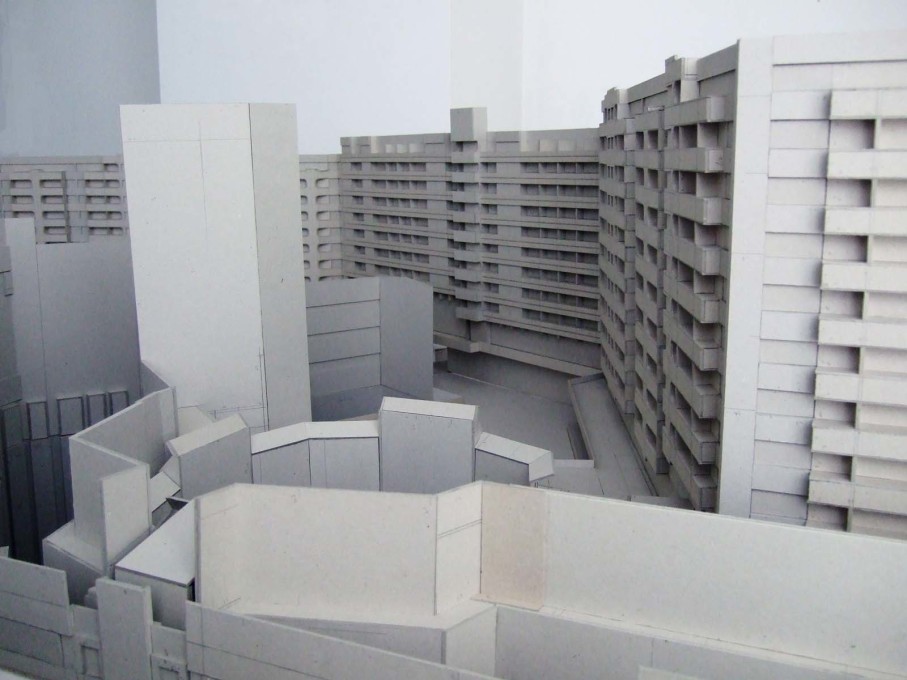

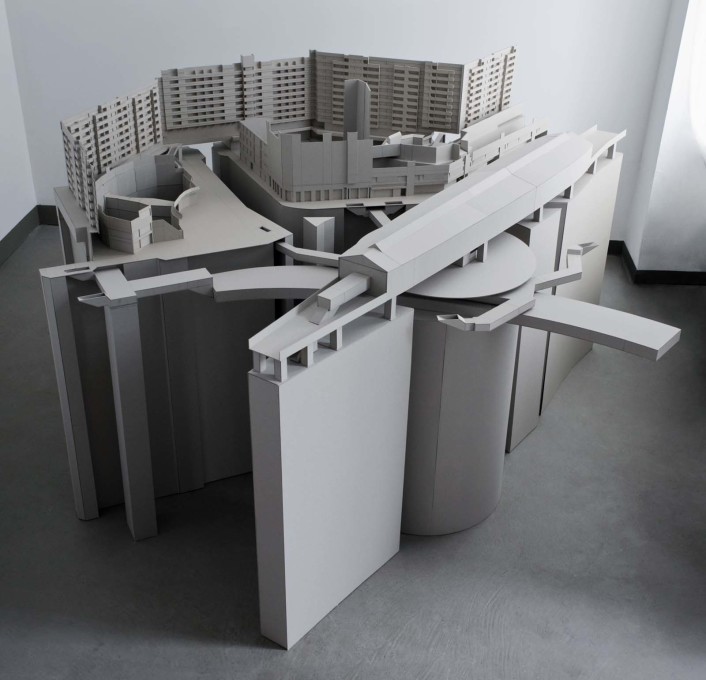

One such site is Kottbuser Tor, a transport hub formed by the meeting of several main roads in Kreuzberg that is dominated by a monolithic building: the Neues Kreuzberger Zentrum (NKZ). Built between 1969-1974, its architect Johannes Uhl had intended it to be the centrepiece of a larger regeneration plan for the area which would have seen a motorway pass just north of the NKZ. Uhl had envisioned a wide provision of communal amenities to accompany his housing scheme, but the comprehensive version of the proposal never came to fruition.

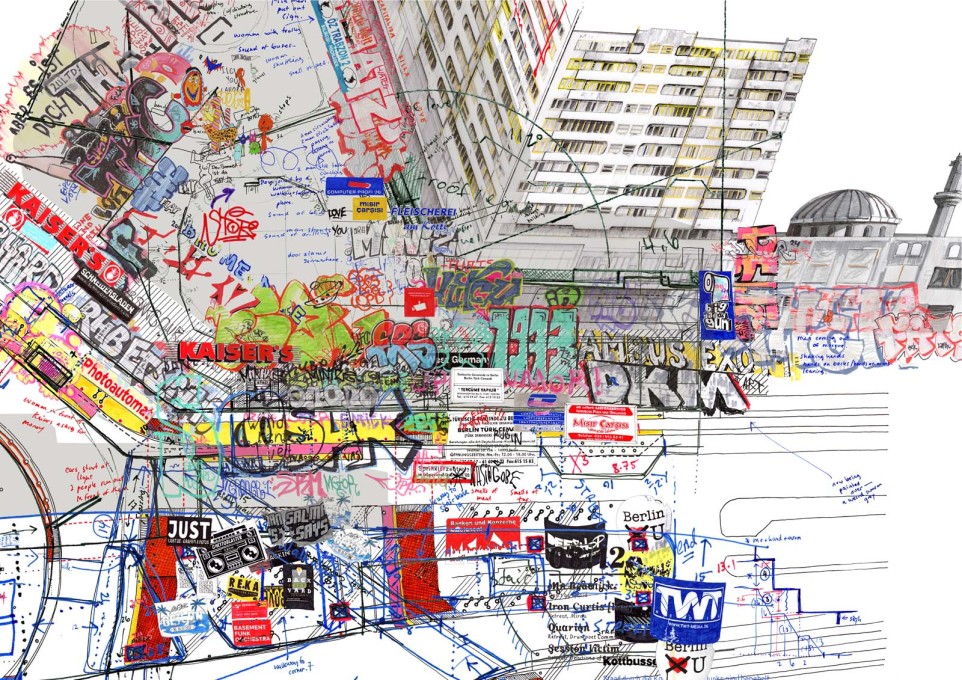

Fassler’s mappings of this area affectionately known as “Kotti”, which have spanned a period of nearly ten years, explore not only the gaps left behind by these ideas never realised but also the negative space created by those which were built. They may appear as voids on an architectural drawing but Fassler reveals them to be anything but empty. Instead, her notations collect together appropriations of and interventions in space by the community that live there. Where redevelopment has failed, repurposing has triumphed: ceilings have been lowered, windows have been blacked out or newly installed, spaces intended as passageways to pass through have instead become meeting places to spend time in.

But Fassler’s practice extends far beyond just encounter with static architecture.

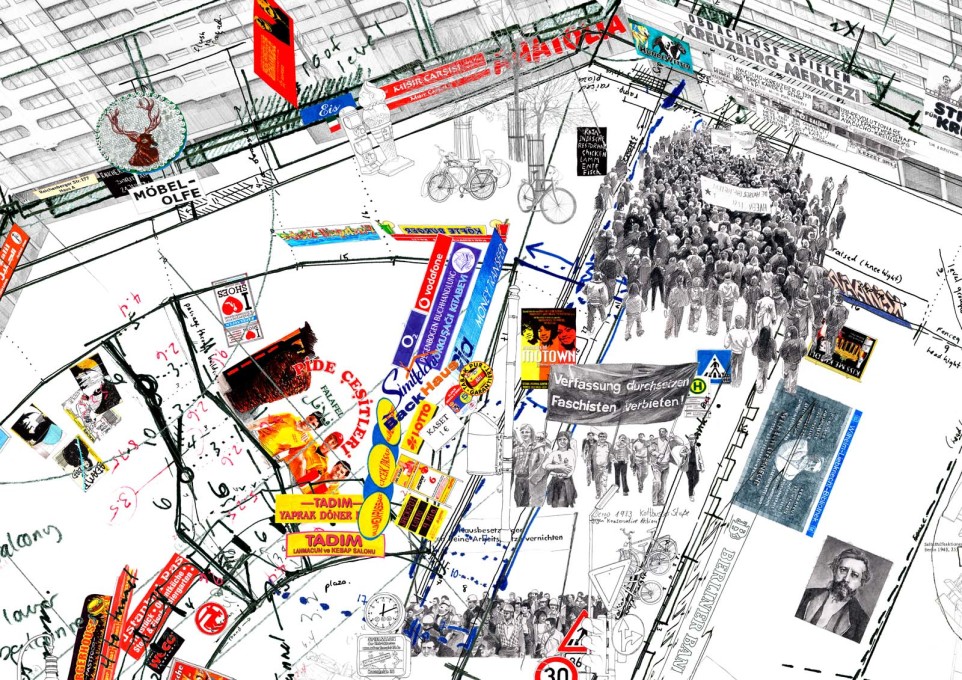

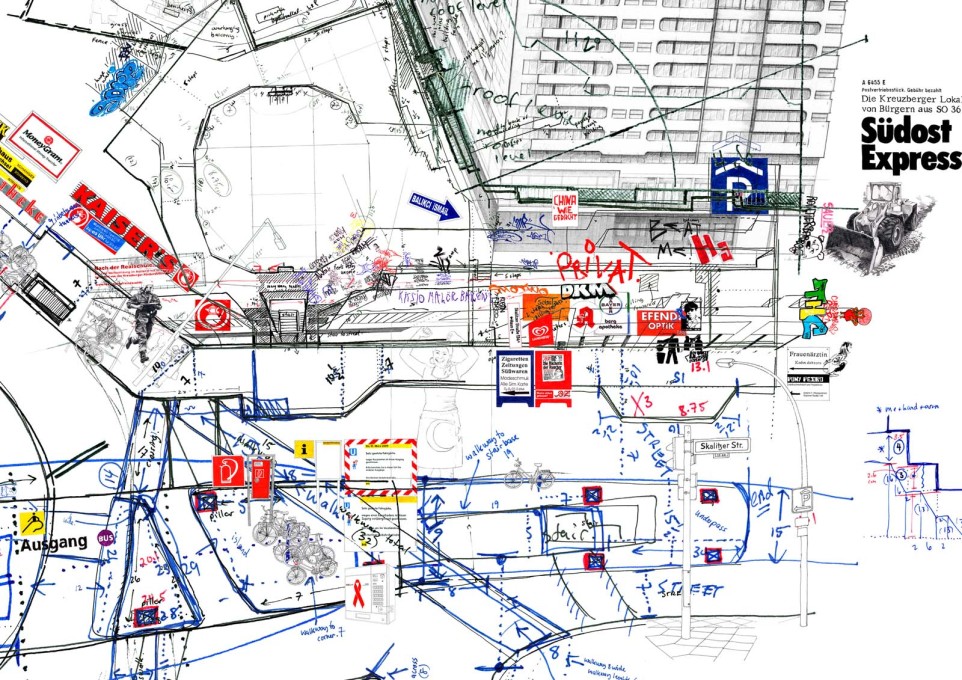

This psychogeographical method also records the literal practice of everyday life. Seen together, her mappings of the site in 2008, 2010 and 2014 evidence a continuing chain of “everydays”, showing what most architectural plans tend to omit (or, worse, misjudge): the way people actually interact with and use their built environment. And all minus hyper real renderings of shiny happy people holding lattes.

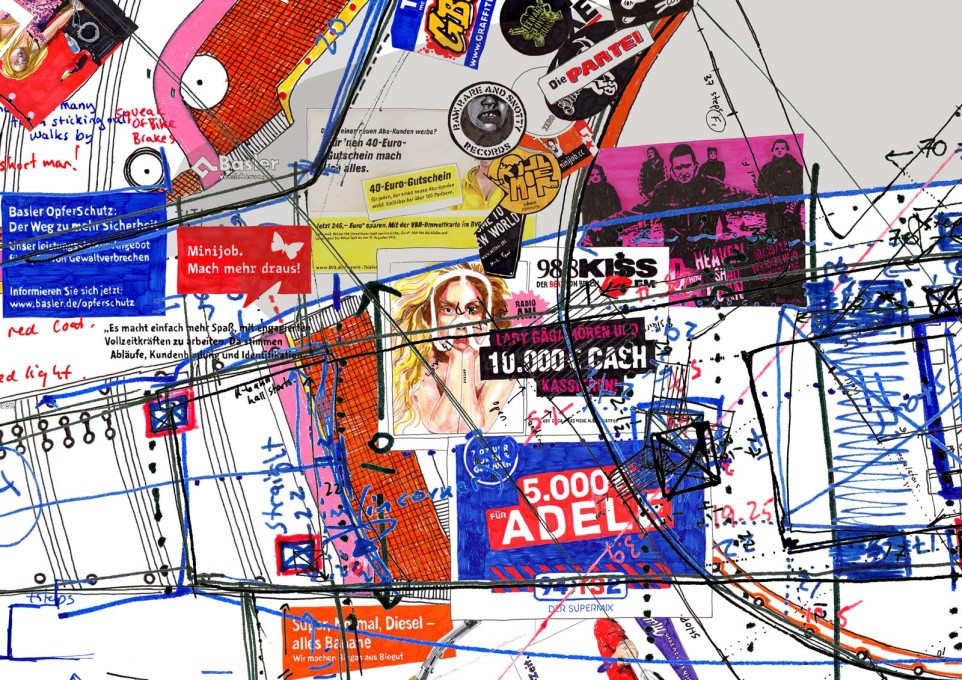

Instead, an explosion of graffiti, shop logos and stickers is overlaid with imagery that includes crowds and riot police, posters and placards, extracts from newspapers and information signs about U-Bahn upgrade works. Often the notations that appear alongside them pertain to a human scale reading of the city: the height of a stairwell being “my height + an arm” or a roof height that equals “me + 1 ½ metres”. Then there are the ephemeral elements which static visuals will always fail to capture: the temperature of the breezes than run through building passageways; the corners upon which the sound of squealing bike brakes is a particularly frequent occurrence; the smell of freshly butchered meat from a shop meeting the smell of newly mixed tar from the road works just outside.

Other processes that can be equally elusive to grasp as they unfold in real time also become visible in this way; gentrification being a perfect example, best signified by the appearance of certain fonts, not to mention the shift from German to English or Turkish seen across many of the signs.

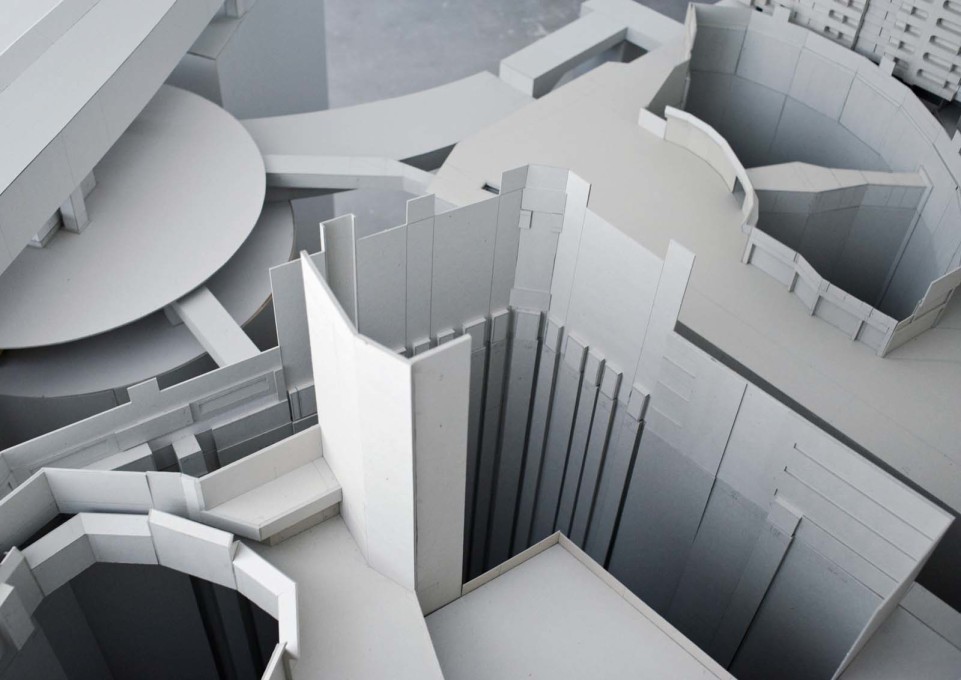

The information contained is undoubtedly disorientating if taken all at once. But by zooming on specific sections, one is able to see where the overlaps happen and how these at-first-sight dissonant elements actually accommodate – even compliment – one other. The effect is a perfect mirror of what is it to actually experience the place in person: this is the noise of Kotti, the sound and vision of a place and its politics. In short, all the stuff that came after the architecture. As if to underline the effect, Fassler has also produced carboard models of the site (scale: 1 footstep = 3cm cardboard) which show these publicly accessible areas minus their public; the contrast with their cartographical counterparts could not be more stark.

Korzybski’s famous dictum resulted from his theorising about the verb “to be” and its relationship to the concept of identity. Following his lead, there is perhaps no more appropriate method than Fassler’s psychogeographical mapping when it comes to chronicling the city famously described in 1910 by art critic Karl Scheffler as “condemned forever to becoming and never to being”.

Further reading: For more drawing – as activity, tool and just plain beautiful image – amble through uncube Issue No.42: Walk the Line.