After forty-five years of service in training Sweden’s architects-to-be, the infamous KTH Royal Institute of Technology School of Architecture has been vacated, making way for a second life as creative incubator. Ugly is now rebranded as bold, while brutalist is sold as authentic. But what is a school without its pedagogy? Björn Ehrlemark, curator of a 2015 exhibition on the old KTH-A as a permanent work-in-progress, delivers a eulogy on a structure full of character that was as much student and teacher as it was a classroom.

The majority of architects practicing in Sweden today passed through here. This is where they learnt their profession, at the old KTH School of Architecture building on Östermalmsgatan in Stockholm.

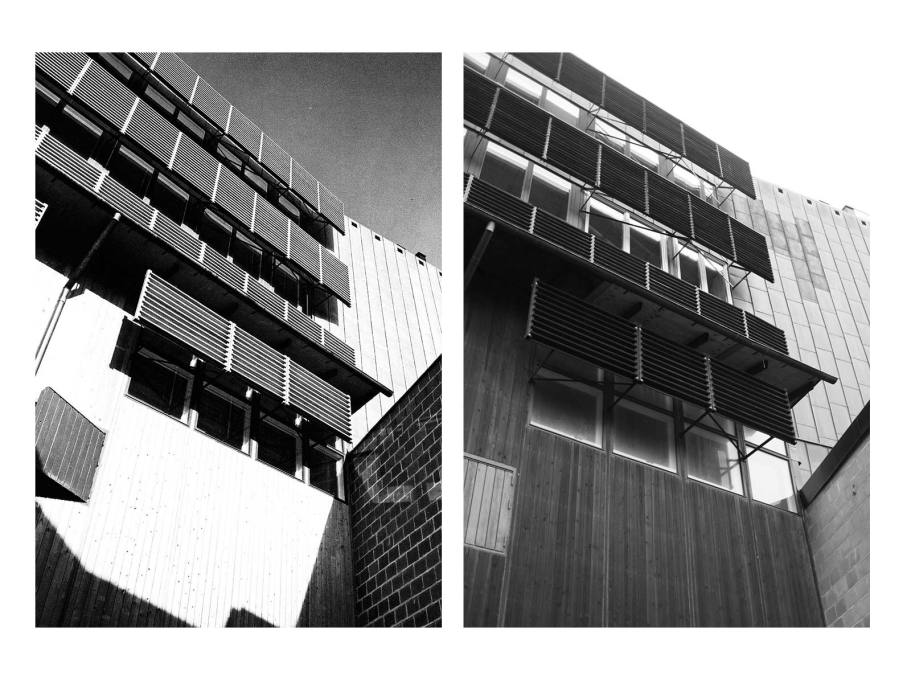

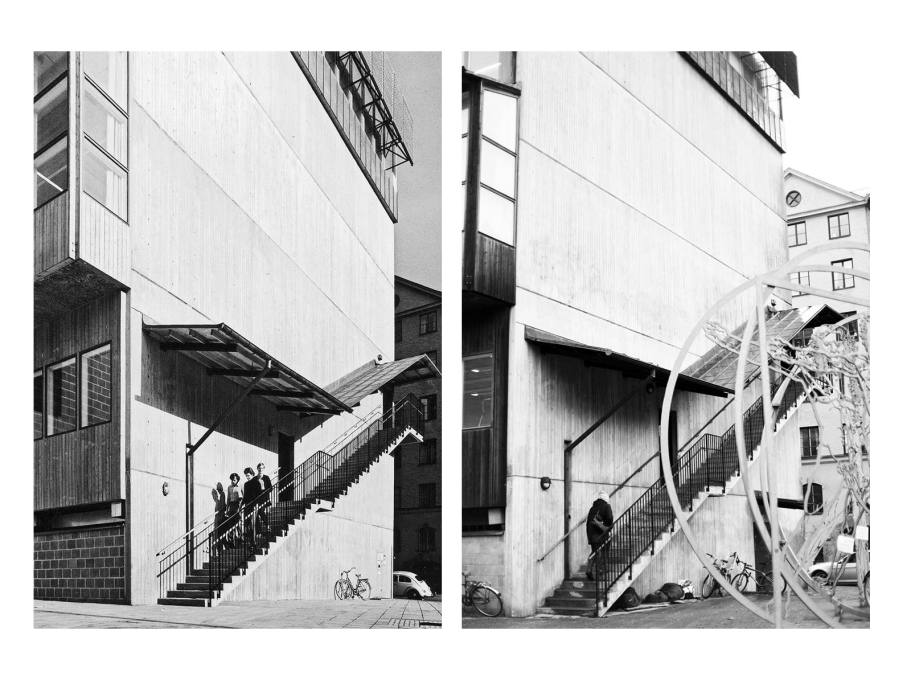

Many Stockholmers already know it. It is notorious for being named the ugliest building in the city several times over by popular vote. Sure, the unapologetic concrete face does not exactly flirt with its pastel-rendered neighbours and the picturesque ivy intended to cover the street façade never took hold. But the epithet is also likely seasoned with added malice both for its contents (“look at the architects in their bunker!”) and its location, the upscale residential neighbourhood of Östermalm. Ten years ago Stockholm’s municipal commissioner for urban planning wanted to see it torn down. But even brutalist bastions become ripe for rebranding with time. The school of architecture has recently moved out to the main KTH campus and the state-owned property company have started to execute their plans to turn the old building into a creative incubator and gastro-foodcourt.

But most non-architects have never seen its insides. Even when it was used as a 1980s bureaucratic backdrop in the Nordic Noir thriller The Fourth Man, it passed widely unnoticed. That is no coincidence. A last-minute concession to a road tunnel that was planned to pass under the site (it never happened) meant the underground parking garage ended up on street level instead. Each of the building’s main entrances are therefore reached via a flight of stairs, giving it the air of a sealed-off medieval castle. So it has been deemed an ugly thing by its critics and praised as a late-modernist gem by New Brutalist connoisseurs for almost half a century now. The truth is of course, that it always has been both, and so much more: workplace, production facility, library, garage, lunch room, garbage dump, courtyard hang-out, storage space, party venue, and too some degree, a second home.

The building was inaugurated in 1970 and was the last to be designed by the university’s in-house architecture office, led by architect and professor Gunnar Henriksson and architect and artist John Olsson. At a time when prefab and standardisation was becoming the norm, the design team worked more or less in isolation on this final project for two years straight. All components – even doors, tables, and light switches – are custom-designed by the architects. And all are drawn up after the same principles as the overall scheme: robust, clean, versatile, discreet.

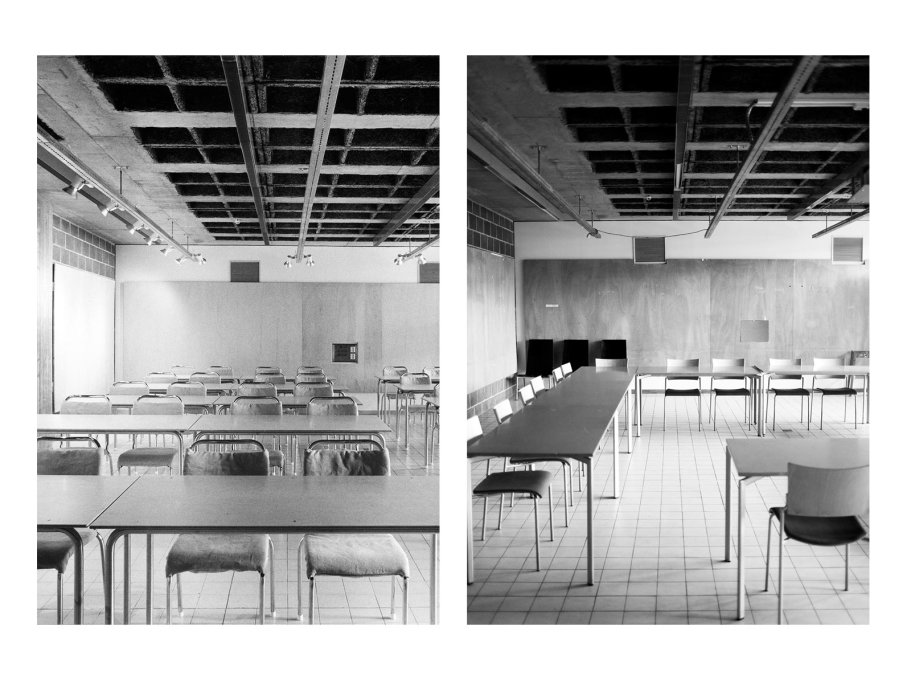

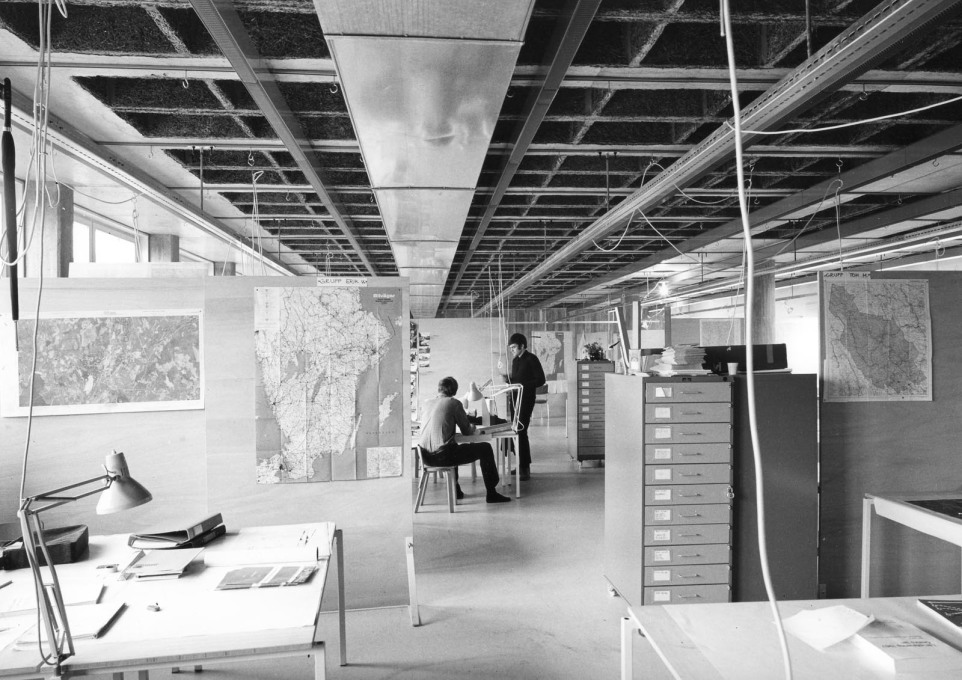

Its expression is that of raw and exposed construction. Columns, floor plates and sheer walls in cast concrete; partition walls made up of stacked ash-grey cinder blocks meticulously fit between the pillars; the lighter courtyard pavilions assembled from I-section steel beams and corrugated plates. It is stripped bare, with a frankness balancing on asceticism. Yet, its lasting impression is one of generosity. The more time you spent here, the more it gave.

For one, it is a pedagogical tool. Building elements are exposed and laid out like an anatomical chart. No, not the simplified tectonics of columns and beams playing in the light, while pipes and ducts hide behind the corner. This is architecture without shortcuts. In the ceilings the electrical gutters – also designed by the architects – are on display, running overhead through corridors and studios. Steel components are a weird reddish orange or bright turquoise, the tints of off-the-shelf anti-corrosion paint. And the original scheme even had the exposed ventilation shafts color-coded blue and red for exhaust and intake in accordance with the conventions of technical drawing at the time.

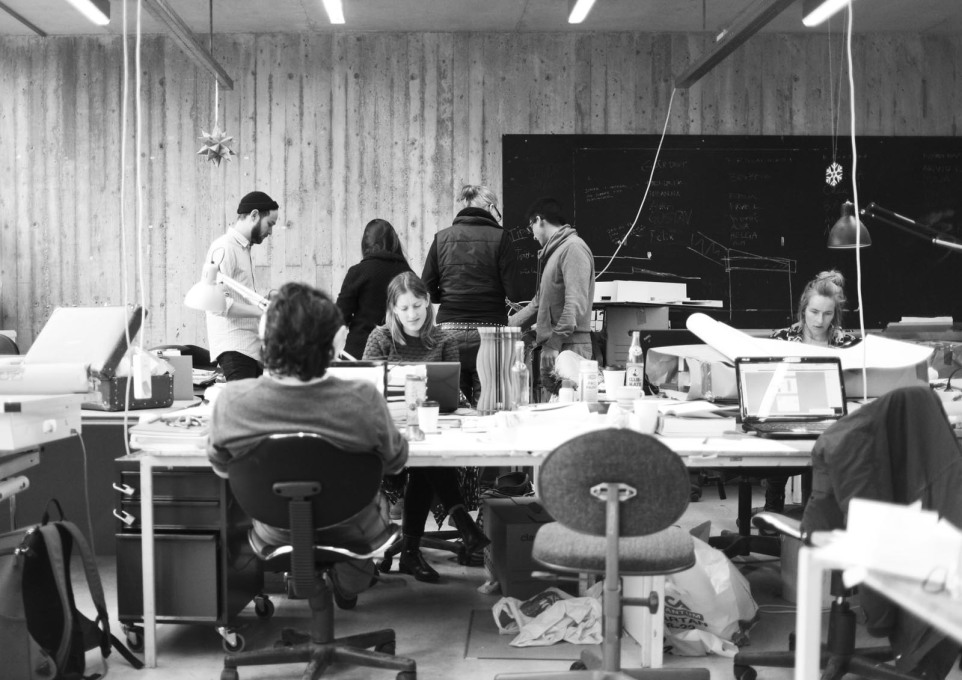

As a piece of institutional architecture, another of its notable features is how it does away with corridors. Faculty offices, facing the street, open directly into the students’ studio spaces, which face the courtyard. The area in-between became a space for students and teachers to have chance encounters and engage in informal conversation. A radical architectural idea wedged into the social order of late 1960s academia, but one that would pass unnoticed for a first-time visitor.

The feature most distinctly illustrative of the ideology of the design also requires inhabitation to be appreciated. In the ceiling of the studio spaces, interlaced with rows of minimalist tube light armatures – designed by the architects – is a grid of hooks. The ceiling system is filled with them, alongside plenty of electrical sockets. You probably do not event notice them until the day you look up from your studio project, desperate for something to hang your model from or to connect your lamp to. Most likely, there is a hook right where you need it.

This is an architecture left raw as an invitation for addition and alteration. Much of the curriculum, for which the building was tailor-made, was replaced in time for its opening. That soon left it with a set of extra spaces – an acoustic chamber, a daylight laboratory, a full-scale construction hall with a massive mobile crane – which served as a spatial resource for unexpected activities. Some of it came in handy when the school introduced a computer lab, others when a fire destroyed the model workshop in 2011. But a loose fit in general also meant there was room for messy, bulky and awkward ideas – the kinds of things that happen at an architectural school all the time, and especially when their spaces encourage these opportunities and ideas to arise. The building was intentionally set out to be permanently unfinished, to be completed again and again by those passing through, each in their own way. It will now be spared from the mess and the noise, but will it then degenerate into a state of restlessness? It seems to need the friction.

Although this building was designed to take a beating, few could have imagined how much of a beating it would actually take. The first generation of students, in the early 70s, complained about a lack of cosiness and added flowery curtains. In the 80s and 90s, it became a venue for clandestine parties. By the 2000s, institutional downsizing meant one of the wings was rented out as office space. In 2011 the fire destroyed the courtyard pavilions, which were replaced by temporary structures and container barracks. And throughout, during 45 years of service to architectural learning, it got pounded on, smoked in, spray-painted, bumped into, glued to, hammer-drilled and had coffee spilt all over. And each semester, as a new generation of architects-to-be came through the door, it was ready for another round.

Björn Ehrlemark is an architect and editor, and co-founder of Neighbours of Architecture. He directed the public programme of the KTH School of Architecture between 2013 and 2016, and curated the exhibition Ugly Duckling about the old KTH-A, on display during the school’s final semester in the building.

Further reading: For more brutalist bastions under threat head to #SOSBrutalism, a database of mid-century concrete structures around the world powered by uncube.