Converting part of an architectural icon into a halfway house for prisoners and ex-cons is not your average brief, but one that Personal Architecture were faced with at the Exodus Cube in Rotterdam. Cristina Ampatzidou talked to the architects and assesses a tricky commission.

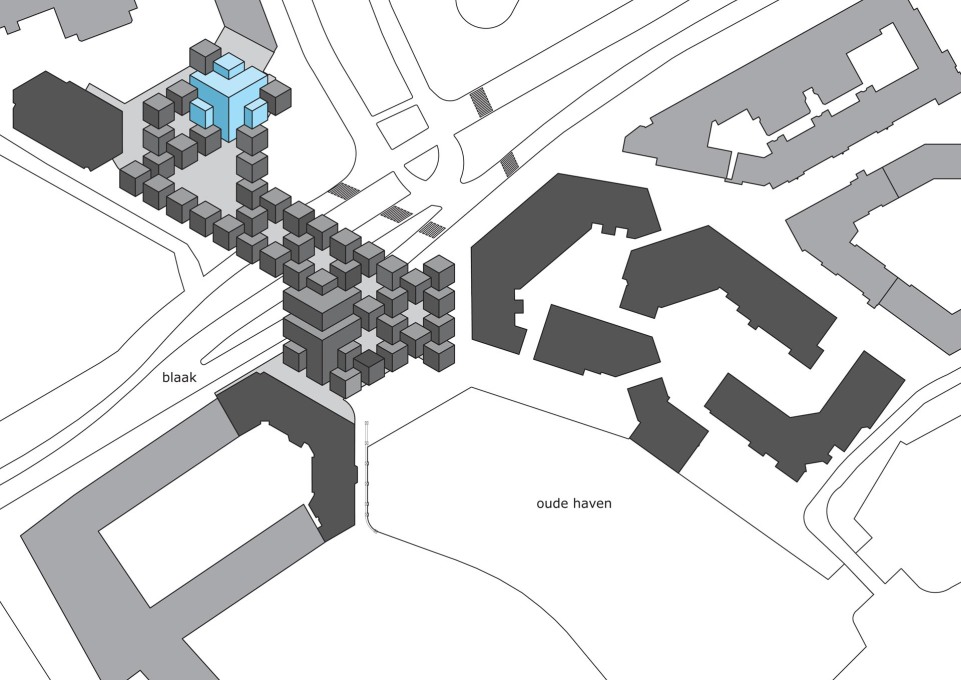

In 1974, Piet Blom was asked to design a pedestrian bridge over the Blaak, one of the main traffic arteries of the city of Rotterdam. Inspired by the Ponte Vecchio in Florence, he covered this in a forest of houses with concrete trunks and rotated cubes of living space as foliage. Completed in the early 1980s, this comprised 40 housing units, as well as three larger cubes, that were designed to host public activities. It became famous worldwide as the “Cube Houses” complex.

Of the three bigger, or “Super-”, cubes, two were used by the Architecture Academy for more than ten years, before relocating in 1998. But the third Supercube remained empty almost since it was built.

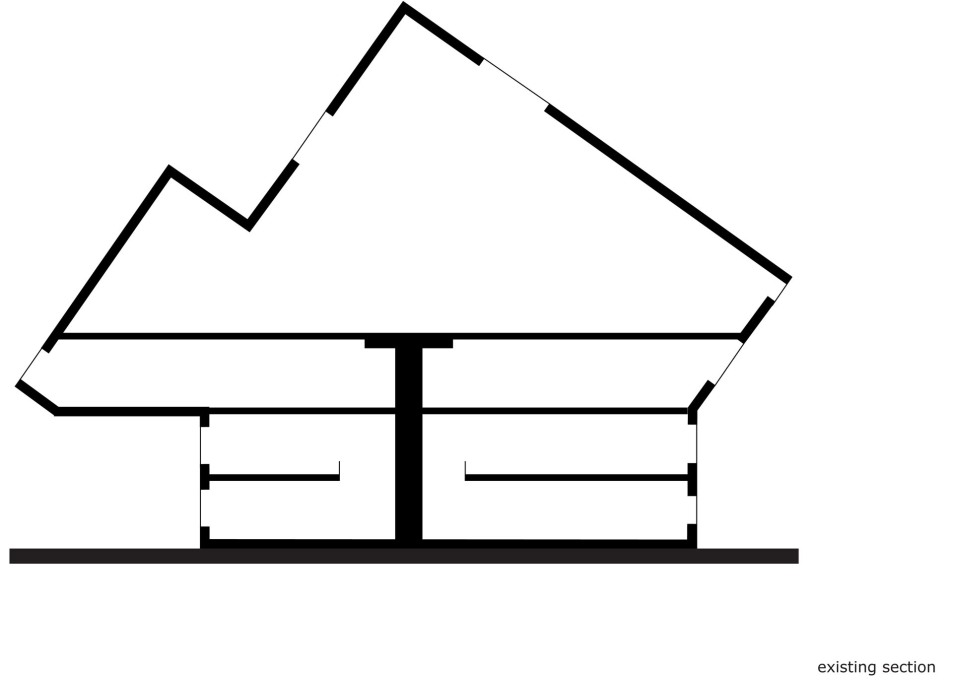

This does not surprise Personal Architecture, the firm that has been renovating all three Supercubes since 2005. Intervening in one of Rotterdam’s most iconic buildings was not something to be taken lightly: “It is an extremely difficult building to work with”, says Sander van Schaik, a partner from the firm. “We originally started working as part of a larger team on the renovation of the two left vacant by the Architecture Academy, but ended up completing that project ourselves.” For no matter how monumental or architecturally interesting, the spaces were tricky to use in their original form: their large central floors extremely dark, their stairs too narrow and too steep for any type of public function and with each floor feeling cut off from one another.

The first two cubes were converted into the 49 room Stayokay hostel, organised around a central hexagonal void with an elevator core providing vertical movement to connect onto bridges leading to the rooms. Following this project, Personal Architecture got the commission for the third cube: “This process gave us a certain amount of familiarity with the complex, which led to our commission to design the third, ‘Exodus’ Cube”.

This cube has a more interesting brief than the other two. It is designed as a residence for up to 20 people, all either prisoners, serving the last nine to 15 months of their sentences and living there to help them reintegrate into society, or ex-prisoners, needing extra help in doing so.

This is one of a series of Exodus homes run by the Exodus Foundation, a nationwide organisation with centres in 11 cities across the Netherlands. Prisoners are placed in an Exodus homes by a judge’s order, while former inmates need to apply for admission.

These centres are designed to help bridge the gap between detention and society by providing personalised guidance as well as the space and time for the inmates to get used to living with other people, whilst supporting them in finding a job and reuniting them with their families. The centres also provide a support network and structure that helps keep ex-cons away from any old acquaintances exerting a bad influence.

Interaction with the other residents is key to this process, both within the house itself and within the “neighbourhood” of the Cubic Houses complex as a whole.

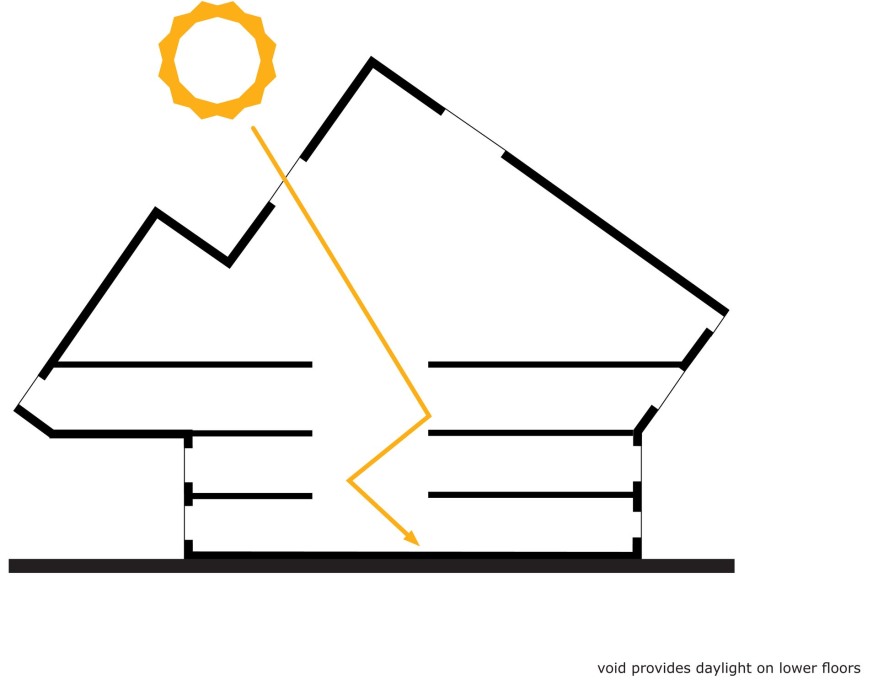

In order to encourage communication among the inmates through the design, Personal Architecture placed the reception and staff offices on the ground floor and the individual rooms on the two middle floors. Everybody has to pass through these spaces in order to reach the communal kitchen, dining room, lounge and computer station situated at the very top. In the centre of the cube, the architects have made a radical architectural gesture: opening up a three by three metre square atrium through the heart of the building: a central void that visually connects all four levels. This layout lets light flow down to the lower floors, and around it are organised the staircase and support facilities: storage spaces, kitchen, laundry, toilets and reception.

This wasn’t an easy thing to do structurally, according to Maarten Polkamp, the second partner at Personal Architecture: “The construction of the building is fairly unique, so it was not only a big gesture in a spatial sense; it was also very challenging with regards to the structural changes it required. We replaced the central column with a square steel frame with four vertical pillars resting at the lowest level on a new floor constructed of reinforced concrete, which connects back to the building’s central column. Certainly it is quite a drastic intervention but we were convinced that it was the necessary thing to do in order to create a livable building”.

This main feature really enhances the interaction among the inmates, as no one can enter the building unnoticed. According to the architects it has been a successful strategy that has positively influenced the formation of tighter bonds among the inhabitants of the Exodus Cube. Externally within the Cubic Houses complex as a whole, however, it has not been so easy for homeowners to accept this new cohabitation, and they started an unsuccessful legal fight against the housing corporation that manages the building. However things have improved since the foundation moved into its new premises and the Exodus Foundation is apparently putting a lot of effort into making the interaction with the immediate surroundings of the Exodus Cube work smoothly.

– Cristina Ampatzidou is an independent researcher, architect and urbanist based in Rotterdam.