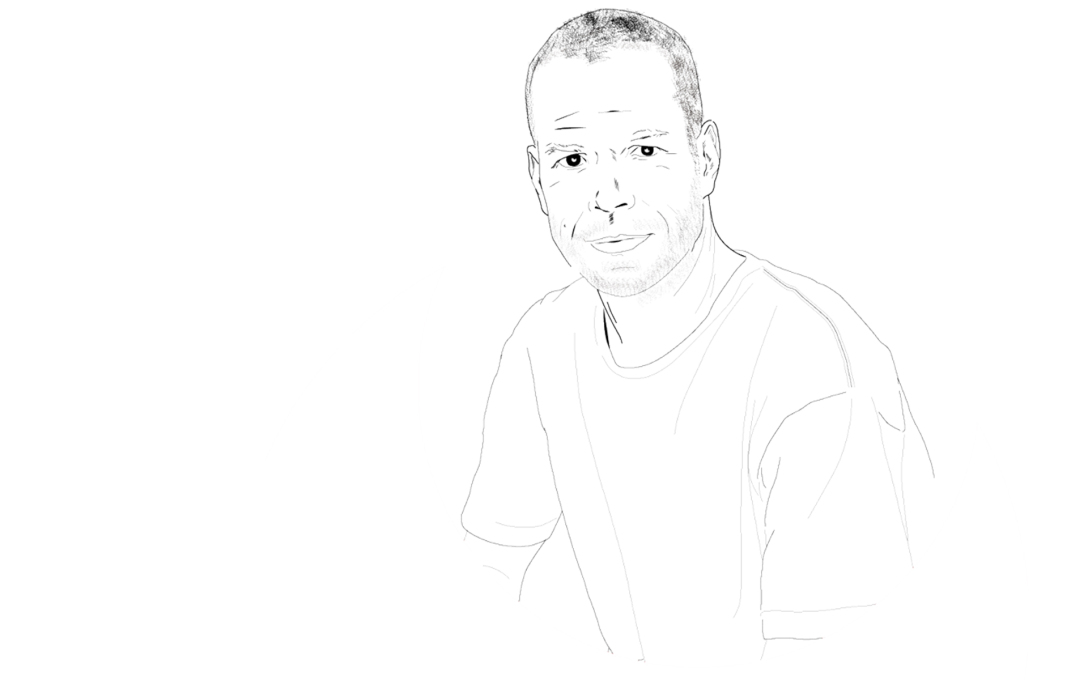

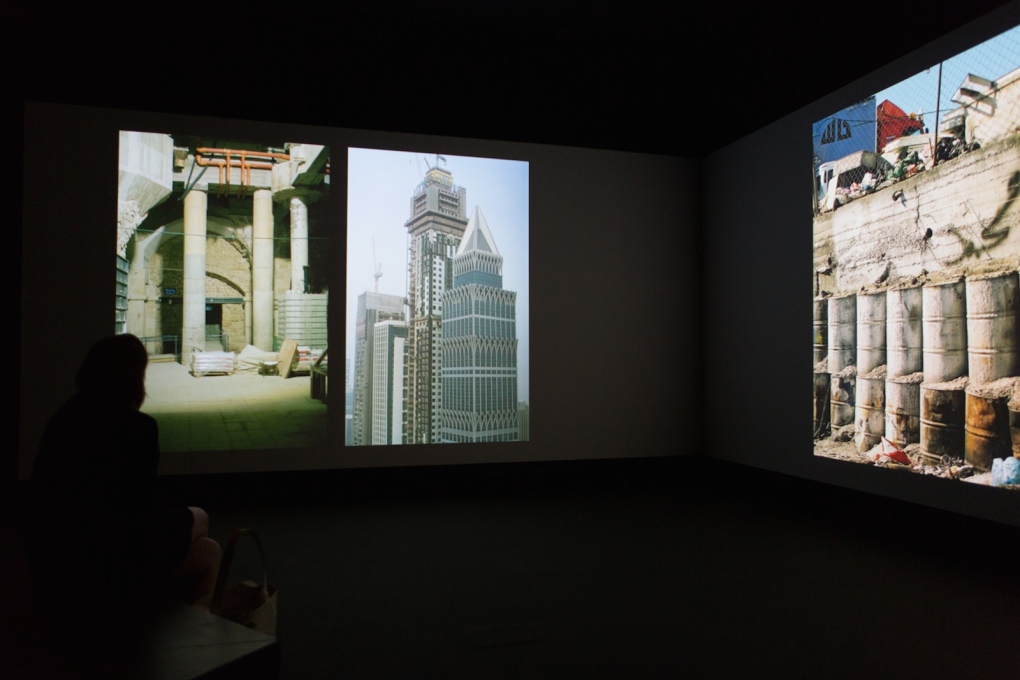

One unexpected addition to Rem Koolhaas’ dissection of architecture in his “Elements” exhibition in the Venice Architecture Biennale, is a gallery dedicated not to “Floor”, “Ceiling”, “Door”, “Corridor” but to “Tillmans”: the work of artist Wolfgang Tillmans. His installation Book for Architects is a two channel video installation, juxtaposing still images of buildings, cities and rooms across two perpendicular walls – from iconic skylines to back corridors, hotel lobbies to emergency housing. Rob Wilson talked to Tillmans about the work and his ongoing relationship with architecture.

It was interesting to see your name as one of the contributors to Elements, that part of the Biennale most closely curated by Rem Koolhaas. Indeed yours is the only name assigned to a single gallery: a “Tillmans” on the Central Pavilion plan amid all the “Wall”, “Escalator”, “Door” and “Balcony” galleries. Did Koolhaas give you a particular brief?

We met first in 2000 when I took his portrait for Index magazine, and he was keen to keep in dialogue, although we have only actually met a few times since.

Originally I was asked to contribute to the catalogue, but when Rem saw my proposal, he said he’d like it in the exhibition. These pictures were not taken for the Biennale, they are part of a long term project – one I’ve been working on for at least seven years – Book for Architects: expressing a desire to communicate and be in a dialogue with architects.

Is this the first showing of Book for Architects?

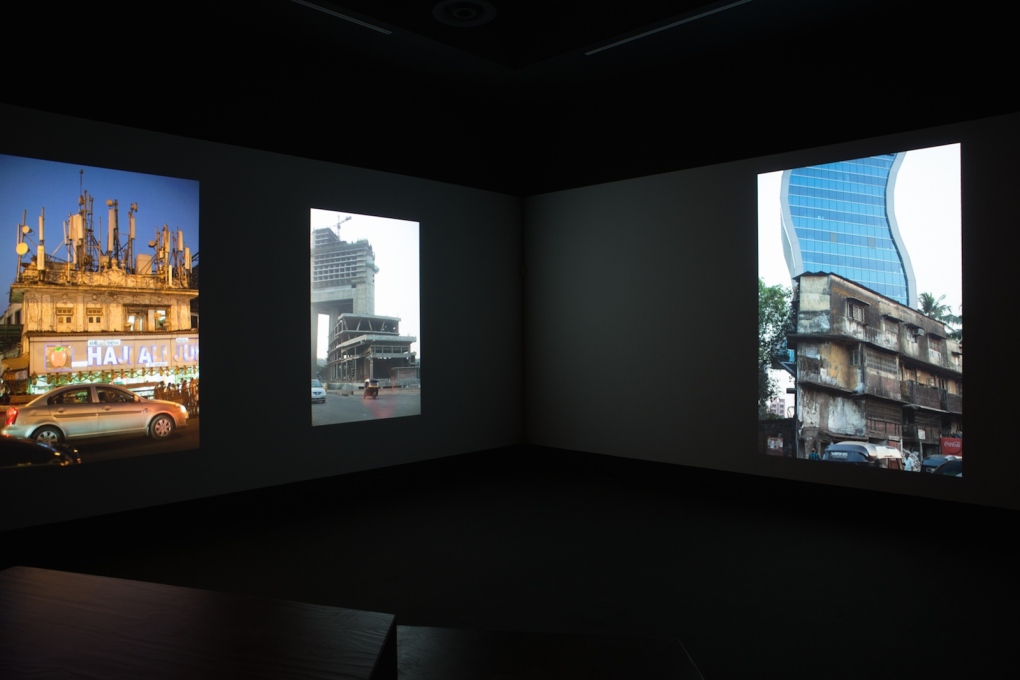

Yes. It is such an in depth collection of pictures that I was never able to show them as part of a general exhibition, because it would tilt the whole show towards architecture. This being the Architecture Biennale finally allowed me to go full throttle on architecture, with 450 pictures. I don’t know whether it will become an actual book, or whether it remains just a nice name for a film of still images. Because it’s not meant to be useable like an encyclopedia, and since I’ve been working on the project, I became aware of the insane amount of architecture books around: the super high specific-ness of them: Concrete Kitchens, for example, devoted only to that! These books are ideas providers, for architects and their clients. This made me think about the role of architecture books. So perhaps it remains a book as an idea, so as not to nail it down.

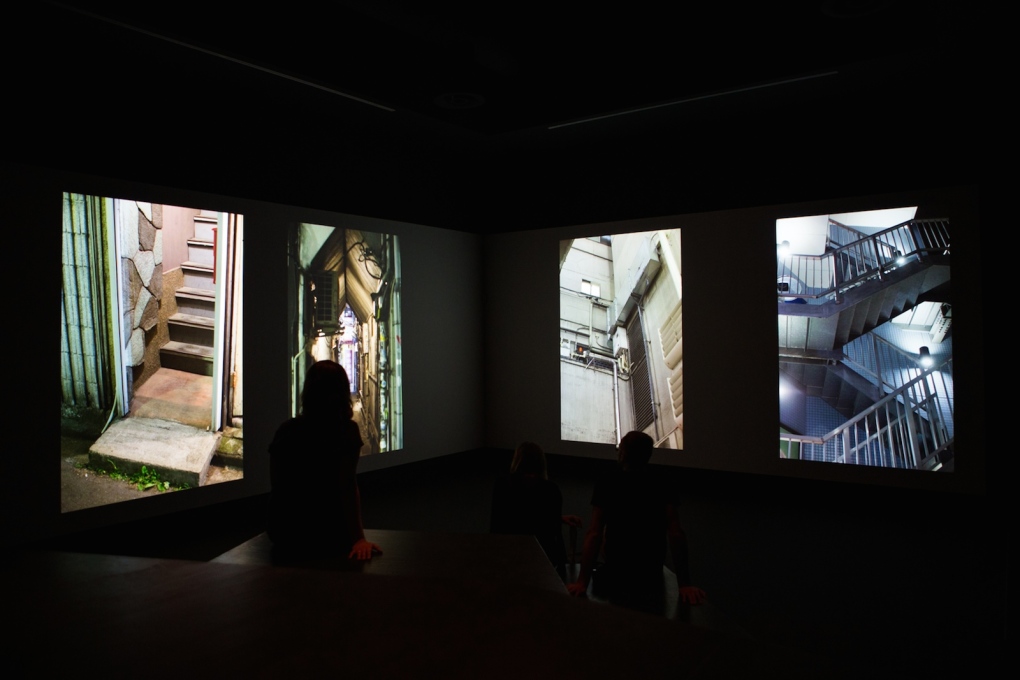

The piece is a two channel still video installation, juxtaposing images across two perpendicular walls. Did you always see the focus of these images as “architecture” or are they more of a continuum with your other work?

There has been architecture in my work all along. For example in 2001, my first touring museum show was called “View from Above”, Aufsicht in German: a group of pictures of cities from above, from towers, planes, different vantage points. These gave the title to the show but were also a category within my work, coming from a particular interest in architecture – how millions of individual decisions shape the overall design of a city. That is my fascination with architecture: all these uncoordinated activities that are not part of a master plan, each an expression of lived reality, each extracting itself from control, from design.

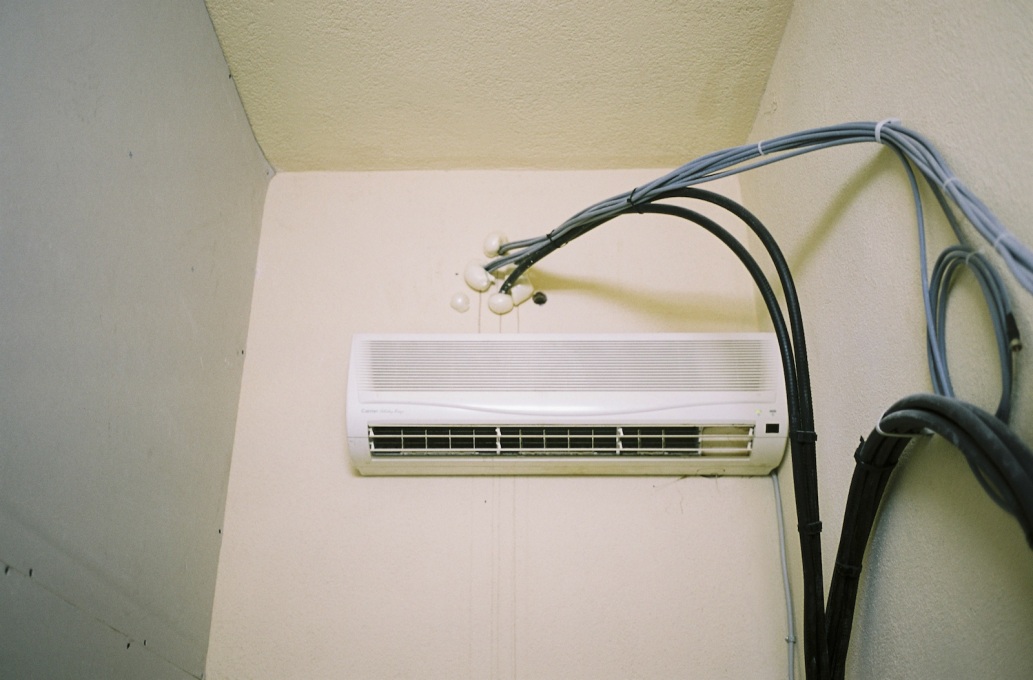

That does come through in your work: it often shows the small adaptations, ad hoc, retrofitted, servicing, knocked together – showing the hands of all the people who’ve come after the architect, and made the building fit for purpose. How in a way a building beds down in reality.

Yes and I guess that reflects one of the biggest interests in my work, one of the driving forces: this fascination for and negotiation of chance and control. How on the one hand, I want to, and have to, control my life as much as I can, and on the other hand, I need to know when to stop, when to let go: to admit chance. If we all lived in equilibrium with these forces the world would be a much better place.

And this is an issue with architecture. Architects are sometimes very vain and have harsh ideas that are driven through and into people’s lives, really impacting them. Or developers who don’t take on board how their commercial single mindedness is reducing quality of life, both in the details and in the larger picture.

The idea of Book for Architects comes from the realisation that given the scale of the impact, there really isn’t much public discussion about this. For instance in London, in the 1990s: what were all these spray-on balconies, and cheap wood façades that looked absolutely shit after three years? Architecture is a long-term project, yet is often thought about in a very short-term way – just for visual effect.

Do you think these issues have become more extreme – with for instance all the “icon” architecture around? – particularly when you compare now to, say, the 1960s?

Extravagant buildings are not particularly new, take the Sydney Opera House. I can still entertain them as expressions of extreme architecture. What I find more politically problematic is what goes on in normal buildings and public places.

Architecture in the post-war period was in the main designed to serve people, to make life somehow better, though not of course with any ultimate wisdom: always with the failings of each period and generation. But there was an idea that we can have housing for all, we can make things better.

I was born in 1968 and grew up with examples of that, and somehow feel connected to it. I was happy to hear Rem Koolhaas saying in his press conference that the fundamental change in architecture since Reagan and Thatcher has been that towards market forces. Architects until then, somehow, were part of public services, connected to the authorities, building buildings for the greater good. Now they are only connected to the market – working either for individuals or corporations.

That is 100% how I see it and how I observe it. I photograph things I like and I photograph things that I do not so much like, and somehow things that are built with a little bit more effort and with a little bit more cost, making the building last longer… I really love that.

And when I see this sort of cheap architecture which is just like cladding on an IKEA shelf – it just breaks my heart. When you travel around the world it’s really incredible how this is everywhere now, and there is no care for how it lasts or how it is maintained…

You present the work as a juxtaposition of images. Why?

The main feeling I want to get across is this sense of the simultaneity of stuff going on, set against the isolation which usually signifies a piece of architecture. You can show a building, but really there are all these different aspects that are happening at the same time: in the detail, the interaction with neighbouring buildings, how it sits in the whole city plan.

The overall arc of the work, of the world you show, seems to be one of places of passage, of moving through, a quite transitory feel. In general the images appear perhaps less personal than those you’ve became known for: there are not so many of people in their homes, of day-to-day living spaces.

Well maybe this reflects what I observed on the extensive trips I took for my Neue Welt project from 2009 onwards. Before that I was mostly travelling for exhibitions in Europe, the US and Japan. An overarching impression I got from travelling the world was the huge number of people in transit and commuting. It takes up a huge part of what one can call global life time. Seen from that point of view my pictures dwelling on this are not superficial but actually show the reality.

But there are interior spaces shown that I have a close relationship with, my parents home for example. A whole sequence of details showing what I grew up with: like the red colour of the bathroom tiles I looked at for twenty years! Obviously in 450 pictures, you can’t cover everything, but I’ve included some interior spaces which I feel I have a different emotional authority to speak about.

I also deliberately cut down on the amount of hotel rooms, hotel lobbies, airports: they come up occasionally, because they are important spaces for all of us now. And there are things like the Flat Iron Building or the new skyline of London. I like to look at the ordinary and the extraordinary: the famous and the unknown, because they are all relevant. You can’t discard one or the other…

You have a distinctive way of showing your work: using the whole space of the gallery: its architecture. Has this always been important to you?

My interest to use the whole room and its potential dates from my first show in 1993 with Daniel Buchholz. I’ve always seen exhibitions as spatial experiences. Because photographs basically sit very comfortably in books, on the printed page: so I never quite understood why they would always have to be only shown in line on a wall. So the gallery allows me something very particular which I have always loved as a viewer myself: to feel the physical presence of the work – coming from an expanse of colour, or being drawn by an image into the corner of a room. I like to work with the supposed weaknesses of a space: the corners where there are service doors, or alarm systems.

A bit like the corners you are attracted to photograph!

Yes. I like to use them in my shows. Often people want to draw attention away from the problem zones. I would rather just stick a photograph on a door and that way occupy it and activate it, make it part of the installation.

And so I guess my relationship to architecture is really as old as my first exhibition. For important exhibitions, I always visit the gallery or museum months ahead. I build models and think a lot about the space and how I want to work it. My shows are always amongst other things a response to the rooms that they are in.

Do you find some spaces easier to work in than others? Do you see yourself also as someone coming in, adapting the original design of the architect?

Of course. The original architect’s decisions affect my own work so much. Architects see museums as particularly interesting projects, where the architecture is in a direct focus alongside the art.

You come across buildings that are very loud. For example in the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, they have these 40cm wide metal brackets at the end of every wall, like all the walls are somehow framed. It’s pure design imposing itself on the art shown on the wall. It’s like this person had this idea and is imposing it on the future, on 50 years of exhibition history. I find that so interesting.

I guess the Guggenheim Museum in New York has a lot to answer for! It is such a spectacularly amazing building: and everybody agrees that that degree of architectural excess, of expression, is justified by the result. It has become an icon for museum architecture, and I suppose people began thinking that museums should be sculptures in themselves. Even minimal architecture is not neutral: it’s super high maintenance and super artificial.

Yes, a lot of architecture is now built so precisely and minimally it seems no longer to have the built-in generosity to accommodate a change of occupation, or allow for any further human intervention, or even maintenance. Indeed it almost fights against it.

Generosity is important for me. The responsibility of the architect is to be generous. A building’s design has to be about its lifespan and not just immediate effect – because it affects so many people’s lives.

You saw this generosity in the 1970s, at least in continental Europe, when in social housing there was always a balcony. I really find both the inclusion of, and the size of, balconies are an incredible sign of the intentions behind architecture.

Often architecture now seems to reduce choice – you are not even allowed to open a window! Architecture has become so much more aggressively authoritarian in a number of ways.

I think this is a signifying sign of the times… this aggression. In my earlier work Neue Welt, which was a book and series of exhibitions, I featured quite a bit of architecture, but also car headlights: looking at how there has been this morphing from a friendlier face to the aggressive face of cars today. That is something that has become a bit of a thing for me. I really feel passionate about it: what are these people, these car designers, putting into our world? What are the desires that they are responding to?

Yes, so many cars now look so beefy, so brutal.

Shark-eyed. That is something that I am very sensitive to: superficial things are actually deeply meaningful. They are an expression of underlying societal conditions.

Whilst you are critical, you also write in the wall text of the images being taken with “a warm eye”.

Naturally we’ve talked more about the things that have changed for the worse, but it’s important to say that this really is a celebration as well: of difference, of good solutions too. And yes the pictures have been taken with a warm eye. It is even a criteria for me when I edit. When I feel a picture was taken with a cynical eye, a judgemental eye – that I was just pointing my finger at something – then I would rather take it out. Even those car headlights were taken with a sense of fascination for the weird optical sculptures that they are. It’s like: Why is this? Let’s think about this. You can’t become a taste fascist yourself.

And the same with architecture. I can’t say I want to show architects what architecture really looks like. I’m saying I have been spending time with architecture, I find it fascinating – and we all need an outside perspective at times. I see this work as a gift, a Geschenk.

– Interview by Rob Wilson

Elements of Architecture

Central Pavilion, Giardini

The 14th International Architecture Exhibition

La Biennale di Venezia

Until 23 November 2014

All installation views of “Book for Architects”, 2014, courtesy of David Zwirner, New York; Maureen Paley, London; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; Institut for Auslandsbeziehungen - ifa.