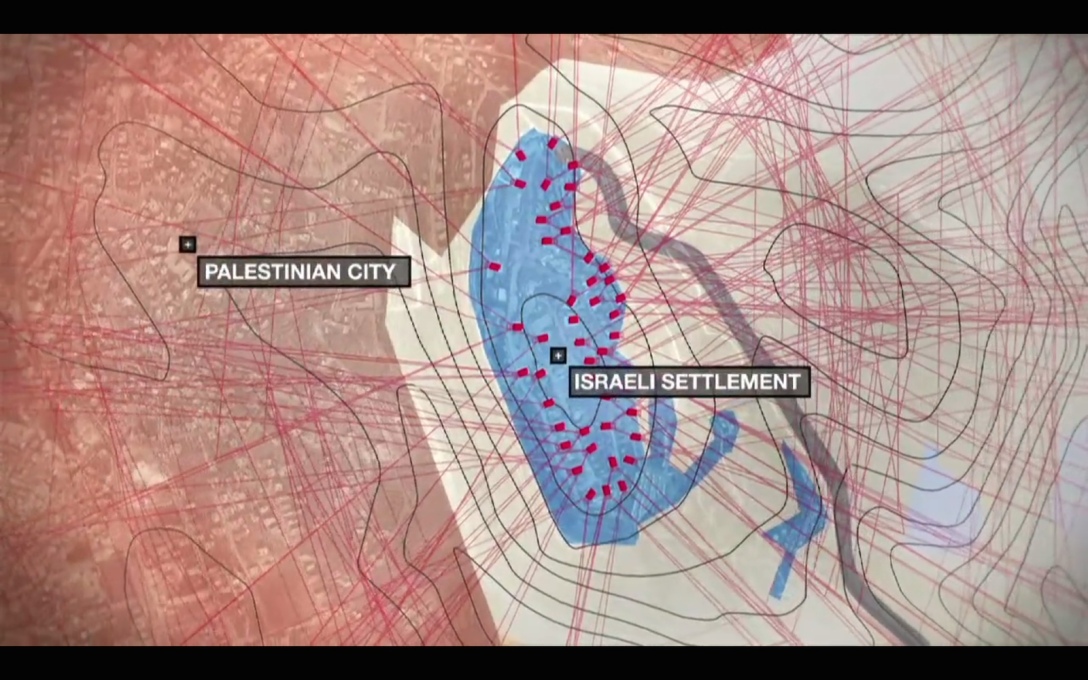

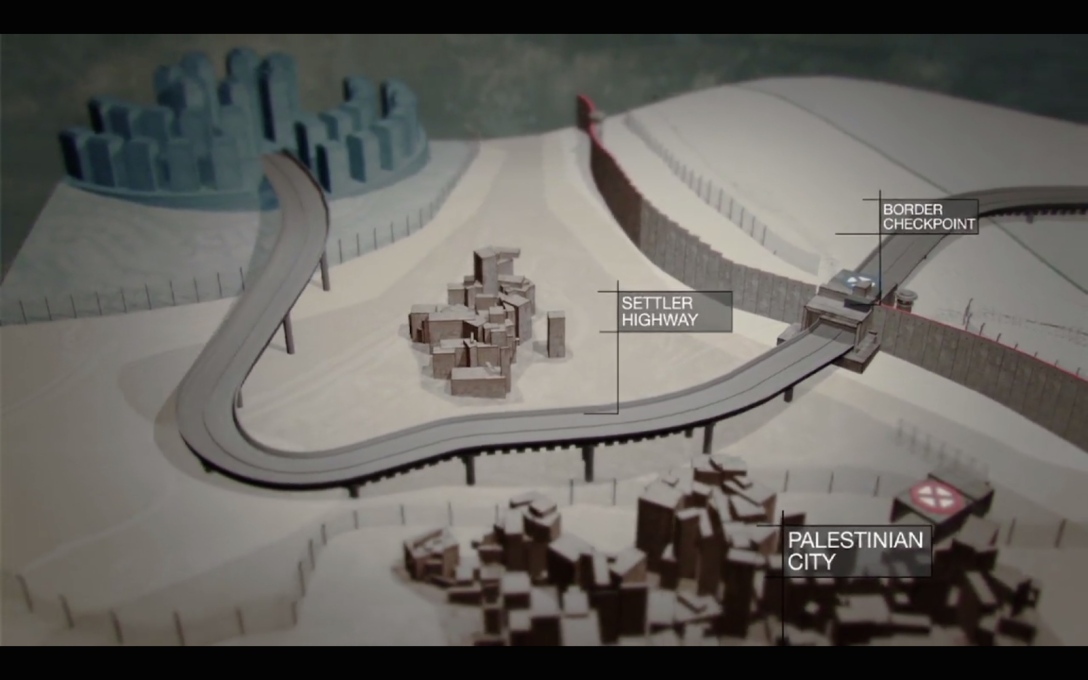

This week in our ongoing presentation of Al Jazeera’s Rebel Architecture documentary series, we’ve interviewed the subject of Episode 3: Eyal Weizman – the one architect who series producer Dan Davies told us was “a rebel on every level”. This video, directed by Ana de Sousa, focuses on Weizman’s work studying the architecture of violence on the Israeli-Palestinian border, where he decodes the history of domination and destruction through spatial clues. Elvia Wilk spoke to him about his many projects concerned with the ethical implications and possibilities of the built environment.

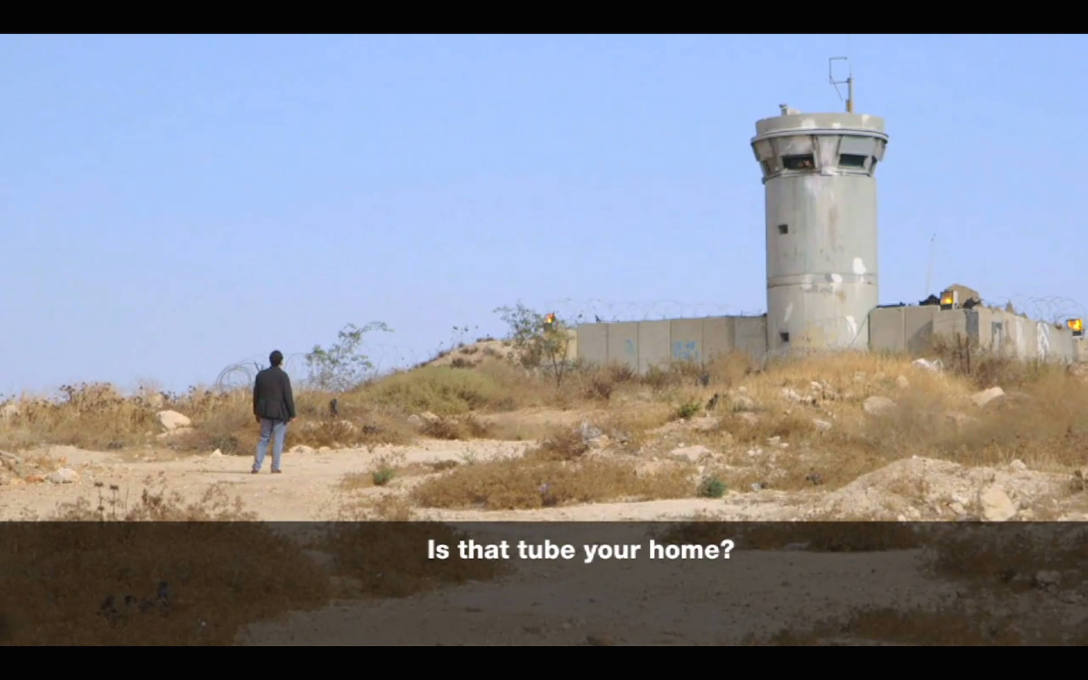

The documentary opens with a scene of you shouting at an Israeli soldier up in a tower at Oush Grab military base: “We used to have a project there before you took over!” Which project was this?

Oush Grab, or the “Crow’s Nest”, is a military base blocking the eastern edge of the town of Beit Sahour in Palestine. In 2006 it was unexpectedly evacuated. One reason is that it’s almost unusable during bird migration time each year, as it sits on the route of millions of birds travelling through Palestine to Africa. Together with my partners Alessandro Petti and Sandi Hilal, I run a programme called the Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency, and during the time the military was away from Oush Grab we worked there, teaching, holding meetings, and building a children’s playground. Then a few years ago the military returned, kicked everyone out of the area, and established the fortress you see in the video.

The practice of forensic architecture, in which you reconstruct a scene from architectural evidence, is necessarily after-the-fact; it’s a reconstructive exercise. That begs the question: what about before the fact? What can architects do as a pre-emptive measure?

In Forensic Architecture we are working as pathologists and archaeologists of the present, in order to intervene in future-oriented political processes, such as this current horrific, gut-wrenching destruction in Gaza. In order for the international community to make sure this level of destruction is not allowed to repeat itself, we must be able to demonstrate that a crime has occurred, in order to regulate or at least moderate future Israeli aggression. Forensics is always an intervention in the future; it’s a presentation of public facts that may be a part of the recent past but are aimed at transforming the abilities of militaries and states from now on.

But is this more a job for litigators than architects?

The forensic agency we’ve established relies on architectural intelligence and methodologies, with architects doing the analysis. We want to wrench forensics from its normal scientific base, and to claim that as architects we’ve a lot to say – especially as most war today is happening in cities. When we established our forensic agency we had very few commissions at the beginning, but now interest is rapidly growing: we’re conducting more than 20 investigations, preparing legal prosecution files for cases in places including Ukraine, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Somalia, Yemen and Guatemala. We’re able to use architecture to open up political processes in all these places.

So yes, I would say this is architecture. But if you’re asking whether it is design – building something up – absolutely! In order to engage in forensics we need to construct and build forums for that kind of evidence to be debated and presented. These are sometimes social and sometimes physical spaces. In one case we converted a former German concentration camp in Belgrade into a public forum. With DAAR we’ve also proposed how to convert former settlements, military bases, and other more “traditional” architectural interventions. But research and practice do not connect in a linear way; it’s not that you do research, you learn something, and then you build there. Sometimes the architecture becomes a way of mobilising research, a site for research to be heard in.

One concept that ties together ideas of research-based design, legal presentations, and speculative proposals is storytelling. A lot of your work is collecting stories from people who were in buildings at specific times, because their story or testimony corroborates the spatial evidence.

Yes, but there is a false distinction between testimony and evidence. Evidence does not present itself in court; witnesses present evidence. They present memories of history saturated with and embedded within objects. Evidence is an entanglement of human memory, human speech, and formal properties.

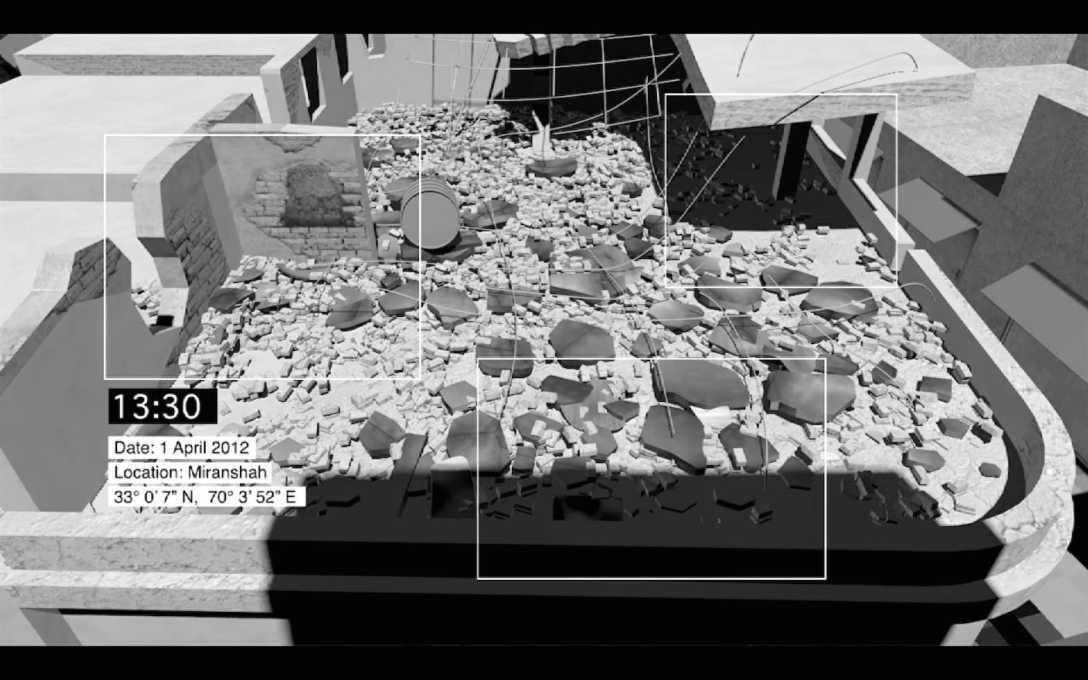

A lot of our work with Forensic Architecture is allowing witnesses – survivors – to reconstruct what has been the worst day of their lives, the day when loved ones, relatives, or friends were killed in proximity to them. The trauma they are asked to present has erased a lot of what is most relevant in their testimony. In order to access that memory, we construct a spatial model of that day, and in the process of adjusting it, a memory slowly comes back. The relationship between architecture and memory is incredibly potent, and so architecture becomes a means of narration.

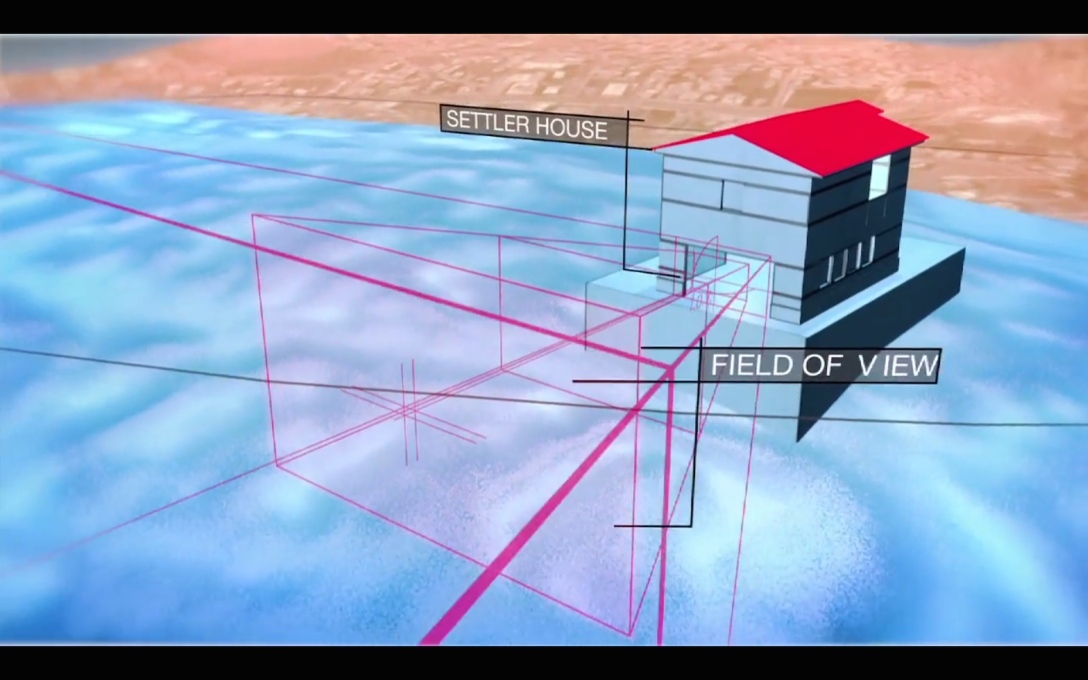

And yet despite the fact that all evidence is transmitted via human perception and filtered by trauma, the threshold of “proof” required in court for something to be rendered “true” has been raised. Images and videos aren’t necessarily enough anymore – why is architectural evidence such as 3D renderings and simulations now so important?

Truth has become a function of bandwidth and resolution. Today we see the very complex assemblage or entanglement between technologies, objects, memories and people in constructing truth. We need to be able to navigate that: if you draw a distinction between testimony and evidence, between the human voice and technological fact, you’re denying testimony its truth value. All truth is constructed or harvested out of the infinite information that exists, in order to make a political or juridical point. We’re swimming in data, and you need to weave the relations between things very carefully.

Thinking of architecture as an interface between reality and truth – at your recent Forensic Architecture exhibition in Berlin, you framed architecture as a “new media” interface. How can architecture be considered a type of media?

Basically, media has the ability to be inscribed with information, store it, and then transmit it. If you accept that materials react to environmental forces – like climatic conditions, temperature, or the consequence of political acts, like a blast – then the materiality of architecture registers that change. Form becomes information. Knowing how to read that change is one thing, but knowing how to mobilise it convincingly, to convert it into truth, is what turns things into media. All material surfaces are sensors in a similar way to a negative in a camera, which translates differentiation in wavelengths into an image. A marble surface can do that, a building façade can do that. The information is stored, and you can read, interpret, mobilise, and claim it, just like with photography.

The series producer of Rebel Architecture told us that the uniting factor between the six of you portrayed in the series is that you are all architects confronting socio-political issues. Does that make you a rebel?

Inasmuch as one understands that rebellion in architecture is an inversion of the normal flow from state and capital to project brief; an inversion of architecture as the physical articulation of the forces of capital; an inversion of the forensic gaze; an inversion of the process through which architecture speaks back through that flow diagramme.

It’s a very hard thing to do with architecture, because its means of construction are land and capital, which are governed by the state and those with money. But if the architect assumes there’s always another client – a “ghost client”, so to speak – not the paying client, but one who is a stakeholder, there is already an intervention within that system, call it rebellion or not.

Our next issue of the magazine is on education, and we’re exploring new architecture education programmes focusing on ethical practice, theoretical understanding, and learning from other disciplines. You started The Centre for Research Architecture programme at Goldsmiths College in London in 2011, fulfilling many of these aims. How did you conceive the need for this?

Goldsmiths is famous for its art and humanities programmes, and it’s incredibly politically committed and experimental. When the school wanted to start an architecture programme, we wanted to keep it away from the regulating bodies of design and turn the gaze back onto society. So we needed to invert the teaching diagramme as well and started with the idea of a peer-to-peer PhD programme, looking at architecture as a documentary form and as a resource for activism. This led us to focus on the Forensic Architecture project, actively producing ourselves as an architectural detective agency – something that almost began as a joke – and have been able to intervene into various processes in the world simultaneously with re-thinking education.

We thought that architecture research, which has a long history, needed a certain bite. It’s not enough to create a map and make some photographic reproductions. Instead – to state it in an intentionally aggressive way – we wanted to weaponise architecture research, to give it teeth and rip open certain dead-end situations. And we’ve been able to intervene in many ways. A lot of the problems in the world now lend themselves to architectural analysis.

– Interview by Elvia Wilk

Eyal Weizman is an Israeli architect, writer and activist. He directs the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths as well as the European Research Council funded project Forensic Architecture.

Al Jazeera airs a new episode each Monday at 23.30 (CET) from 18 August - 22 September 2014. For details please visit Rebel Architecture or subscribe to the uncube newsletter. Watch the full Episode 3: “The Architecture of Violence”, directed by Ana de Sousa, below: