Daniel Libeskind met up with uncube’s Florian Heilmeyer and Sophie Lovell – in the highly appropriate setting of the Grand Hyatt hotel on Potsdamer Platz – to discuss how radically modern Berlin actually was in the 1960s and how he feels that today the city is in grave danger of losing both its radically progressive reputation and its identity.

Mr. Libeskind, do you consider yourself a “radically modern” architect?

I don’t think you can use that term anymore. It is already a historical term. But I think in general there are two kinds of architects: One kind is aware of history and incorporates it in their work, as they know that they are part of an ongoing dialogue. The other kind rejects history and decides to act like architects of the 19th century – or any other historic style. But even belonging to the first category doesn’t make you a “modern” architect anymore, I don’t think. The term refers too much to a history that has already passed.

Do you remember when you first visited Berlin?

Yes, I came here in 1987 when I won the competition for a housing project for the International Building Exhibition in West Berlin, which was unfortunately never built. But I already knew a lot about the city from my childhood in Poland: we were always coming across images of East Berlin in books and magazines, or in my stamp collection. The images of East Berlin were colourful and glossy, it really was an important point of reference for the entire Eastern Bloc. So when I finally came here, I was eager to visit both parts of the city. Friends and colleagues showed me both sides of the Wall, and I remember being fascinated with how similar it looked on both sides. I mean of course it was more colourful and less dangerous on one side, but both sides were imprisoned. West Berlin was obviously far better subsidised. It was full of interesting people who didn’t want to join the German army, and the art scene was incredible!

You found East and West Berlin in the ’80s to be similar?!

Well I guess my view was a bit prejudiced by being raised in a communist country. I couldn’t judge the city only by its buildings, but by the political system and the freedom they offer. I was never fooled by nice new flats. If you are not free, you remain a slave even in a pleasant environment. The fundamental difference was that in West Berlin people could write, think and say whatever they wanted. What both sides maybe had in common was a belief in the future – the future not only in terms of today and the day after, your job or the weekend, but as a much bigger idea. The future of the entire society as a better, enlightened, ideal, or even revolutionary, tomorrow.

This belief in a better future was integral to the propaganda battles between East and West since the 1950s, when each political system tried to prove their strength and outshine the other.

Yes, definitely. The devastations of the Second World War, the reconstruction that followed, the physical separation of the city and the competition between the two political systems lead to a very special climate in Berlin. The fierce competition between East and West led to many ambitious projects. Which side could reach a more enlightened future sooner than the other? Whose future was the better version?

Do you remember which buildings in Berlin you were most eager to visit when you came in 1987?

I went straight to the Neue Nationalgalerie, then over to Scharoun’s Philharmonie and the Staatsbibliothek. But I was also eager to visit private houses of Mendelsohn or the Luckhardts, I went to Siemensstadt, Gropiusstadt, Onkel Toms Hütte … and I was interested to see the big developments in the East, too, like Marzahn and Hellersdorf. I wanted to see all the many, many different kinds of Modernist structures and the traces of Modernism’s history in Berlin. That’s what makes Berlin such a great city, that it has always been a modern city since the very beginning.

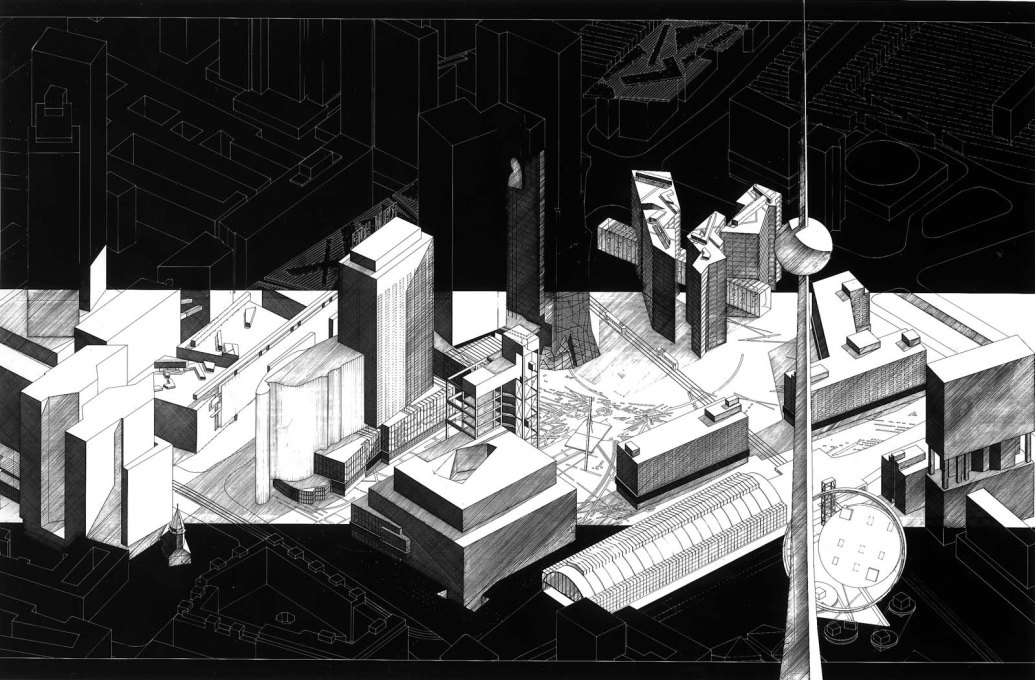

What do you think did the 1960s added specifically to this rich Berlin tradition of modern architecture? Do you think they were specifically “radical” times? Were they different on each side of the Wall, or rather similar?

I believe that many protagonists of the 1950s and ’60s on both sides of the Iron Curtain basically shared the same – maybe “radical” – ideals. They had strong connections before the war, went to the same universities, had the same teachers, read the same books. In the 1920s, the avant-garde in Europe, also in Moscow and especially Berlin, had created a very strong ferment of radical, fascinating ideas. But this avant-garde was crushed in this great black historic hole of Stalinism and the Nazi regime. Most of its members went into exile and died in poverty or oblivion, but their ideas didn’t die. In the ’50s and ’60s architects and planners started to reconnect to their radical concepts. So whether you were building a new prototype housing complex in the East or the West, you had very similar points of reference. That’s why they sometimes don’t look so different after all, especially seen in retrospect.

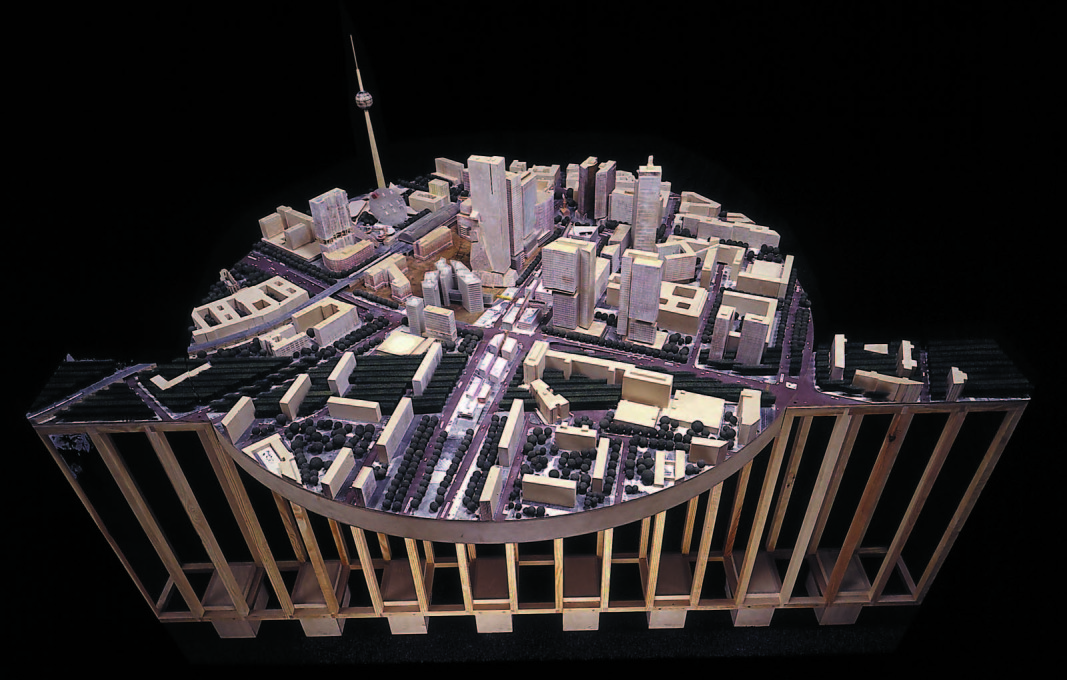

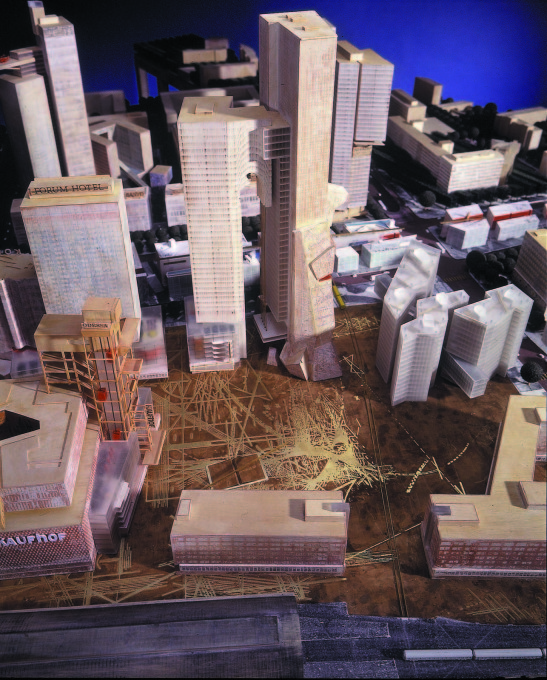

In Berlin both East and West acted in a very close relationship being physically so near to each other. Ideas and concepts were reflected, sometimes as though seen in a slightly distorted mirror. The radicalism also evolved out of the devastations of the war; the old city didn’t exist anymore and the past in general didn’t seem like a very good point of reference. Instead the 50s and 60s believed in very basic values: a healthy and good life, and moving forward, not back in time. I think that East and West Berlin, despite being in a symbolic political competition, were sometimes almost building in parallel, pushing each other further. There also were a lot of differences, of course, in the quality of the buildings for instance, also in the intended political symbolism. But the similarities outweigh the differences.

Do you think there is a false nostalgia involved when we look back and perhaps find the 1960s so much more ambitious and optimistic in terms of architecture and urban planning?

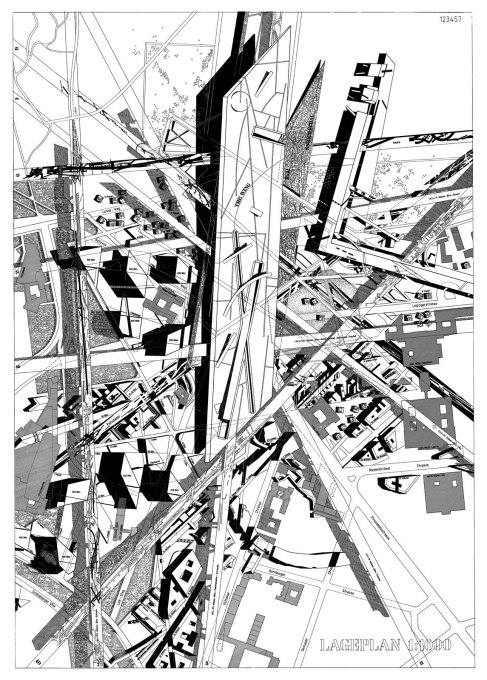

I don’t think there is any false nostalgia in looking back at those times and the built projects with some well-deserved appreciation. I remember when I participated in the competition for Alexanderplatz in 1993 the entire discussion was focused on what to tear down. Actually the basic ideas of Alexanderplatz are not so much different from, for instance, some central spaces in Rotterdam where people wanted to keep their modernist environments. But in Berlin there was such an incredible urge to get rid of the buildings from GDR times, in order to connect back to times even further back in history. If there is any nostalgia involved at all, then it might be because we look back at a period that wasn’t all about money-making, capitalism, private interests and privatisation of the public sphere.

Speaking of nostalgia: Have you seen Berlin’s new palace currently under construction?

Yes, unbelievable! It is almost done! I am sure that with Neil MacGregor as director it will be a fantastic cultural place, but it is not about that. Cities have a strange connection with the people living in them, and even one big building can change that connection profoundly. I am worried because, for me, Berlin always had this avant-garde streak and I wonder when – with a couple of buildings like this – Berlin will be finally turned into a completely different kind of city.

What do you mean?

Berlin always had an interest in experiments, in the ’20s, in the ’60s or the ’80s. Some things might not look so experimental to us anymore, but they were in their own time. In my opinion this severely changed after the unification of Germany. If Berlin wants to remain true to itself in the sense of being a homestead of avant-garde, progressive, future-oriented thinking, it will have to change some things.

I think the era of rebuilding structures of the past has now passed because going back in history has never really worked – anywhere. Conservatives argue that the old city was such a good city, that it is much safer to rebuild in that image than to move forward to something unknown. But do you really want to have the old city back with all its disadvantages that are so easily overlooked? Does this actually solve the current challenges? You need affordable housing, places for kids and families, more public places. If you just follow the old building lines and volumes, you are actually treating the city like a piece of art or a museum that has to stay the same or that was finished at some point.

You are quite passionate about the potential of this city aren’t you?

When I was at the Cooper Union in the 1960s, there was a very different idea of Berlin going around. I met with people like John Hejduk, Raimund Abraham, Peter Eisenman and Richard Meier, and all of them were constantly talking about Berlin as this progressive, forward-looking place. I really got infected with the idea of Berlin back then.

That’s interesting, since all the architects you’ve just mentioned came to build in Berlin during the ‘80s and as far as I remember they were all rather disappointed with what they finally realised here.

That’s right. Because the idea of Berlin exceeds the limits of what you can actually do here by far. [laughs heartily]

Even Le Corbusier was seriously disappointed with the Unité d’Habitation he built here. He had to drastically change his concept to meet the West Berlin social housing regulations. In the end he was so angry that he even withdrew the title “Unité” and said that the building must be always be called a “Unité d’Habitation, Typ Berlin”. Now everyone just calls it the “Corbusierhouse”, which he would probably have hated.

You know, I was very lucky to realise the Jewish Museum in Berlin at all. It was so hard to get this building done. When I met with [Berlin’s freshly appointed Director of Urban Development ] Hans Stimmann he told me that if he had been in power just one month earlier, the building would have never received building permission. He even seemed to be proud to say it! I was lucky that the competition was decided in a time of change, when the old modes of control had vanished and new ones weren’t yet established. The building found its own momentum despite many experts claiming that it could never be built, but with strong support for the project from others. I am very happy with that building. It is deeply rooted in the history of this place and couldn’t have been built anywhere else. I have no reason to call it “Typ Berlin” at all.

I guess this has also something to do with how “radical” architecture actually can be.

I once had a discussion with Jacques Derrida and he asked me how I deal with my art as an architect. As a writer, he could write some obscure and radical text on any subject he liked and could always find some independent French publisher to publish it and get it out to the people. But with any building you actually want to get built, you need so many legal permits. That is the big difference. It is about the bonds and ties and regulations of architecture.

Where do you see Berlin’s future heading?

Many places face similar discussions: how to deal with the legacy of Modernism, of obsolete political systems, of the good and bad parts of their history. Berlin is a special case though, because it has a different function in the mind of the world. It‘s not just another city that is developing. Berlin is this symbol for the rise and fall of political systems – the overcoming of evil maybe. This makes it a really unique place. The danger I see for its future development, is that if Berlin doesn’t follow its own tradition of a constantly changing, progressive, optimistically avant-garde place for new ideas, then it will not be Berlin anymore and the aura will move to another city. Berlin will become just a place like so many others. Not to break with its history of a continuously changing avant-garde is the task Berlin faces at this very special moment in time. If Berlin wants to stay Berlin, then it has to stay radically progressive and constantly changing.

– Interview by Florian Heilmeyer and Sophie Lovell

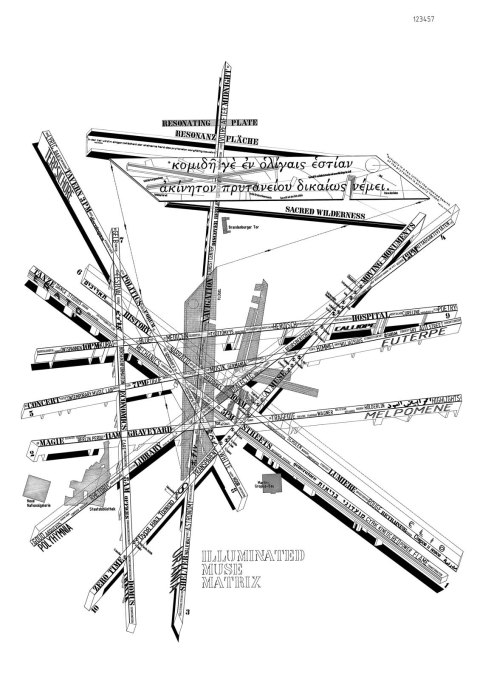

Radically Modern. Urban planning and architecture in 1960s Berlin

until October 26, 2015

Berlinische Galerie

Alte Jakobstraße 124–128

10969 Berlin

Germany

uncube are media partners of Radically Modern. Please check the related articles, including interviews with the exhibition’s curator Ursula Müller and with the radical Austrian architect Georg Kohlmaier.