Following hot on the heels of our story on the Richard Wagner Museum extension by Staab Architects, here is another tale of an invisible architecture and extraordinary museum building that also hides its light under a bushel, but in a most spectacular way. Slovenian architect Boštjan Vuga visited the Gallo-Roman Museum of Lyon in France for uncube and found a 1970s building, designed by Bernard Zehrfuss, that is still highly avant garde in its approach.

The Gallo-Roman Museum of Lyon opened in November 1975 after nine years of planning and construction. 40 years on, it is still an exceptionally contemporary and inspiring museum. Upon my visit in February 2016 the museum happened to be hosting a temporary retrospective exhibition about its own architect, Bernard Zehrfuss, one of the major figures of twentieth-century French architecture. Thus my experience was split three ways, between the museum space itself, the museum collection and the temporary exhibition about the architect’s works intertwined with its permanent archaeological collection.

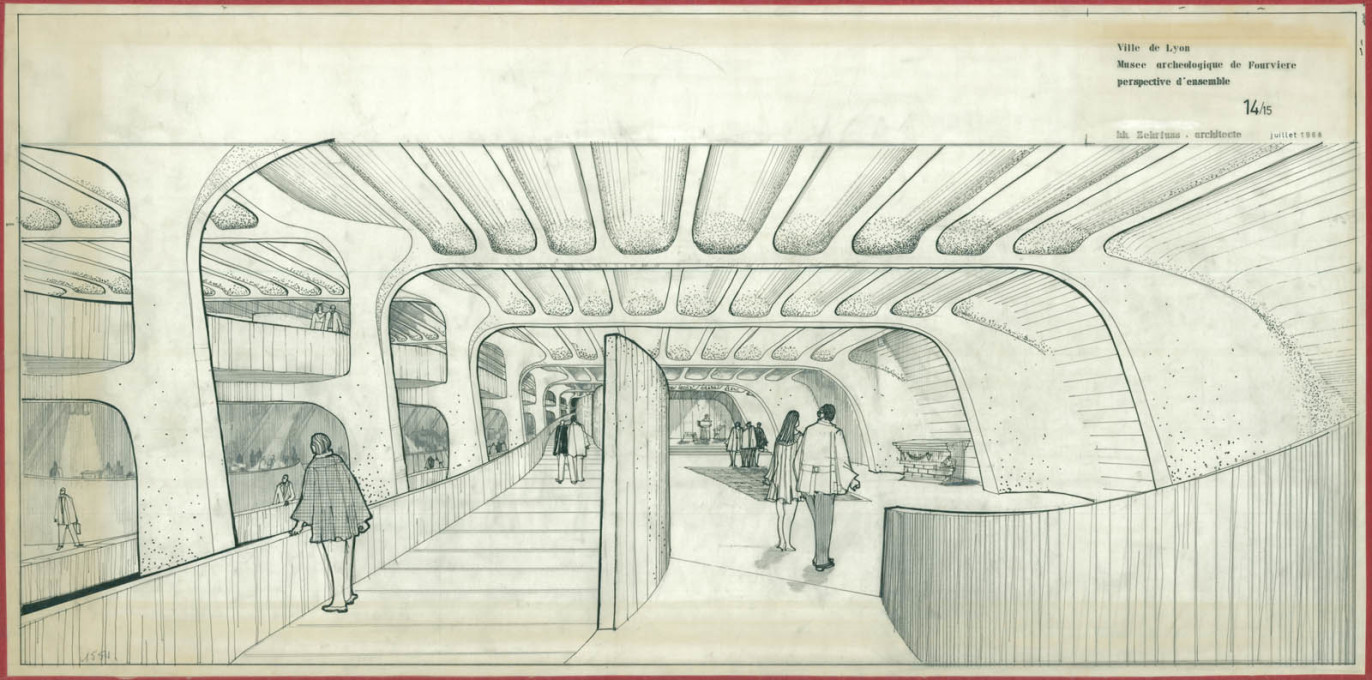

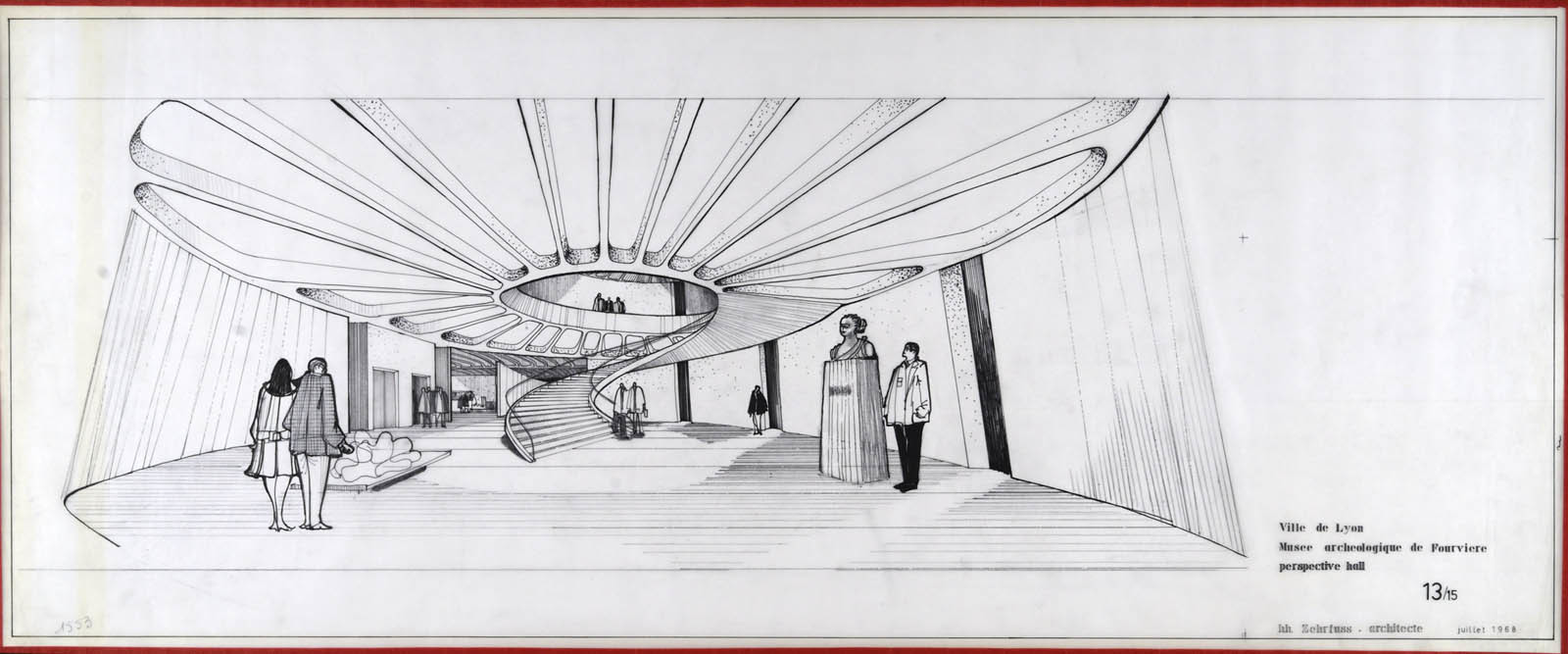

The actual promenade spatiale through the museum begins at street level, where one enters a low, discreet concrete building and then continues past the reception and boutique to a spiral staircase, which acts as a well penetrated with light. The visitor can then choose to begin their experience of the space and exhibits – including Zehrfuss’ architectural models and sketches – either via a rapid descent along the building’s central ramp, or, rather more slowly, by descending a spiral staircase which connects the “chapters”, or thematic display rooms, with the archaeological exhibits.

The ceiling above resembles daisy petals, radiating outwards like an asymmetrical sun. As we descend further, we reach the main space of the collection: 18 metres high, 312 metres deep and 6 metres wide, comprising three, smoothly connected descending levels.

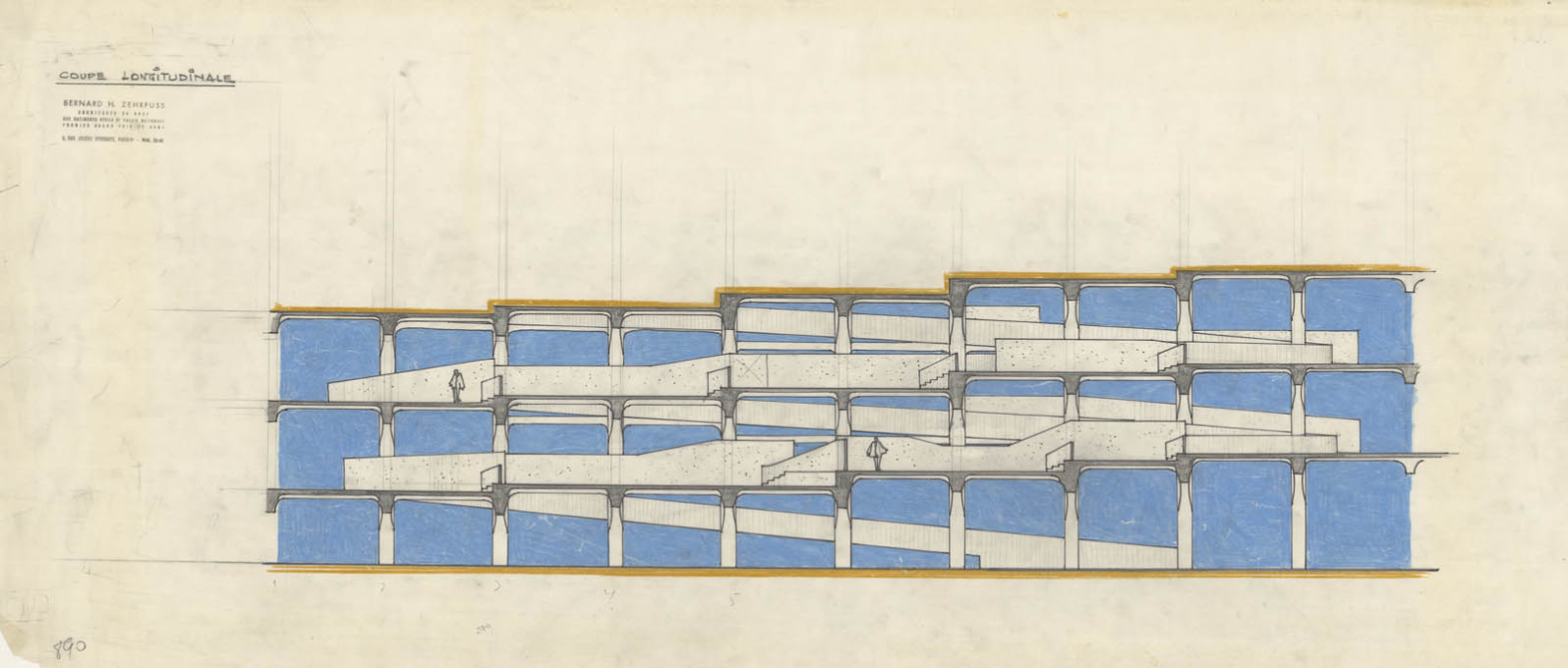

Eleven porticos support the ceiling and the prefabricated concrete level slabs. Each of the porticos consists of three pillars and beams joining them. The heights of the pillars vary, so that we experience exhibition display rooms of different heights as a result. The pillars are not parallel to one another: the inner one is parallel to the diaphragm wall; the outer one to the broken line of the façade; and the central one leans against the construction at an optimal angle. The pillars are split in the middle to integrate service and technical elements.

The resulting porticos represent the basic skeleton of the museum which function cinematically, generating long, short and framed views into the spaces with varying atmospheres and characters. The sloping ramp, which winds from the central pillars, presenting the fast route through the museum, gives views into the rooms from different angles. If the horizontal view from the ramp reveals the timeline of sequential exhibition departments, then the view downward allows views onto the storage, service and maintenance rooms – those spaces which are usually concealed from public view. Many of the exhibited items of Roman archaeology within the museum are heavy and difficult to move, thus the ramp serves not only for public circulation but also, very practically, to allow service circulation. I find this fusion of the exposed and presentable with the stored but visible to be daring and seductive. Whilst visiting, it becomes obvious that the development of the museum’s interior space and the installation of the heavy museum collection were carried out simultaneously.

Passing through the museum reveals the scenographic approach taken by the architect – the display is integrated into the architecture itself. For example, viewing shafts penetrate the floor level and frame a view of mosaics laid out below. Similarly, specific lighting was developed for particular items of the exhibited collection as well as the space itself: the shafts and partitioning between the thematic display rooms function in a way that triggers our inclination to move downwards and continue exploring. The museum’s space is far from neutral. It is not a simple container where exhibits are presented, but an experience machine where the interior and the collection are in symbiosis with one another.

Halfway down the ramp and at the end of the tour, two light tunnels create a visual connection to the outside. This creates the perfect osmotic gradient between the archaeological site of the two Roman amphitheatres outside and the interior. Only at this point does it become clear that the porticos actually form the structure of an artificial hillside, which contains the museum. The museum is an invisible structure, buried in the Fourvière Hill, blending into its immediate environment and not obstructing, but rather, emphasising the importance of the archaeological site it shares.

This “underground concrete cathedral” was created by cutting into a natural hill, opening up an underground space, then the skeleton with its ramp and floor was implemented before burying the whole thing once again with soil and landscaping. Viewed from the Roman amphitheatres, only the two square-ish tunnels – like two eyes – give any clue that something is going on within the hillside greenery.

My visit to Zehfuss’ Gallo-Roman Museum left a strong impression on me as a practicing architect. The fact that the building is hidden – invisible even – buried in the hill, lends it a proper sustainable character with constant atmospheric conditions inside. There is Zehfuss’ dry pragmatism with the non-mediated and the non-hidden – service and exhibition space in one volume. There is a strong sense of the museum’s function and awareness of the fact that all of the exhibits are so heavy – you can actually sense their weight in the layout of the space. And finally there is the way that the visitors’ movements and perception in the interior space, as well as their relation to the archeological site, is orchestrated and constructed. All of this makes this forty-year-old museum so contemporary and inspiring: so antimonumental.

– Boštjan Vuga is a cofounder and partner of the architectural office SADAR+VUGA. He studied at the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Ljubljana and at the AA School of Architecture in London. Boštjan was a guest professor at the Münster School of Architecture, TU Berlin and Berlage Institute. Recently he taught at the Confluence Institute for innovation and creative strategies in architecture in Lyon.

Further reading: For another sneakily hidden museum, have a read of Florian Heilmeyer’s review of the new Richard Wagner Museum extension by Staab Architects in Bayreuth: Taking a Staab at Wagner.