-

The rise of the Polish urban movements

By Igor Stokfiszewski

-

Igor Stokfiszewski, a journalist and activist of the independent socio-political organisation Political Critique, looks at why the recent successes of Polish urban movements seem to indicate that that people are ready for a different way of practising democracy.

Poland’s local elections that took place in November 2014 followed the usual pattern, with the ruling coalition of the Civic Platform and Polish People’s Party retaining their control over all the major cities. But there was one political surprise in the final results. The urban movement, known in Poland under the umbrella term Ruchów Miejskich (Urban Movements), which ran for the first time in elections as a nationwide coalition of city activists, won the mayor’s seat in Gorzów Wielkopolski in western Poland, and a number of city council seats in big cities like Warsaw, Poznań and Toruń.

Although a newcomer to the electoral race, the Urban Movement dictated the direction of most election campaigns. Their demands ended up in the electoral programmes of mainstream political parties, which scrambled to attract grassroots activists to their lists in an attempt to capture the young leftist vote.

So what is this new political force, and could it permanently transform Polish local and state politics?

Local initiatives

In late 2007, a group of residents of the Rataje district in Poznań, western Poland, organised to defend their right to have a say in the planning of their neighbourhood. The mayor of Poznań and the city council had proposed to transform the derelict post-industrial zone of the neighbourhood into a new residential and commercial area. Local residents, on the other hand, insisted on building a park and a recreational area.All images courtesy Galeria Urban Forms

-

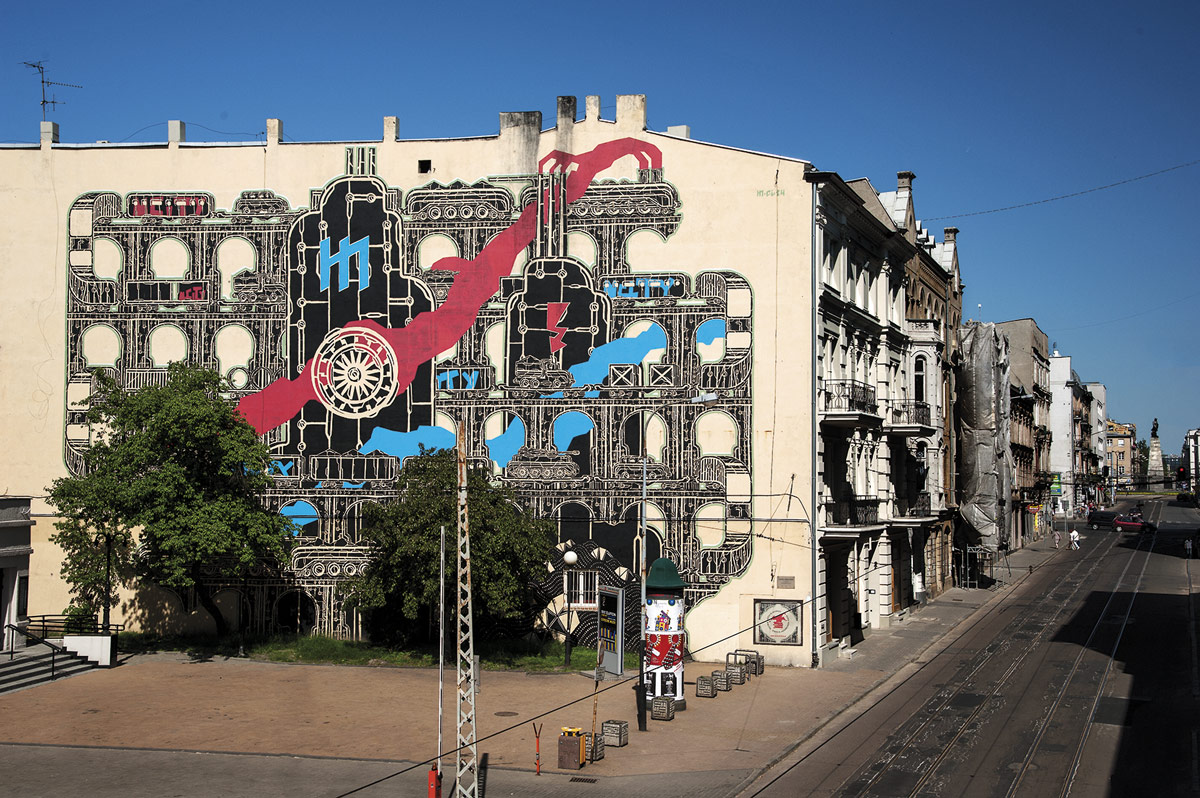

In 2009 actress Teresa Latuszewska–Syrda founded an independent, non-governmental organisation, later to become known as the “Urban Forms Foundation” (FUF), to “change the city space” of Łódź by “raising its quality and aesthetics”. Art historian Michał Bieżyński also becamed involved at the end of that year.

-

FUF raised funds to create giant urban artworks on tenement housing walls throughout the city by invited street artists, stating: “We want to promote ‘living’ culture and art, direct them towards people and make it possible for them to take an active part in organised events. We propagate every activity that aims at revitalising our city and county as well as the whole country through artistic creativity.”

During an annual festival, new images are added to the city’s streets. There are now some 38 murals in place from artists including Os Gemeos, Inti, Aryz, M-City, Etam Crew, Otecki, Sepe and Chazme.

-

They mobilised the community, organised protests, wrote petitions and publicised the issue in the media. The resulting negative publicity made the situation uncomfortable enough for local officials to concede to public pressure and withdraw their commercial development proposal. This was the first sign that a new social force was emerging with the potential to affect urban policies in Poland through civic engagement.

Grassroots activities began to surface in other Polish cities around that time. Activists from Sopot in northern Poland started calling for participatory budgeting following a model set by the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre in the early 1990s.

In Łódź, central Poland, an informal group of active citizens organised themselves around the issue of cleanliness of public spaces. Gradually, these groups merged into a movement calling for citizen participation in the transformation of the post-industrial area of the city, just like in Poznań. Łódź was an important industrial centre up until 1989, when its textile industry collapsed and many industrial buildings lay abandoned and derelict.

In Warsaw, urban activists organised demonstrations for the preservation of green areas in the centre of the Polish capital, against hikes in public transport fees and against privatisation of municipal buildings.

In the last few years, groups like Right to the City, Inhabitants’ Forum, and the Housing Movement have emerged in almost every Polish town, bringing together individuals of various ages, social, and cultural backgrounds. These groups were involved in a variety of campaigns to re-assert residents’ rights to their neighbourhoods and towns: from writing petitions to organising protests, from pickets and demonstrations to occupying vacant buildings, setting up squats and blocking evictions. Their political appetite grew with time. In 2010, Poznan activists formed “We, the Inhabitants of Poznan” (My-Poznaniacy), a social electoral committee to contest local elections. They received almost 10 percent of the votes, but with an electoral law favouring big political parties, they failed to get a seat on the council.

Formulating the urban commons

This electoral experience facilitated the 2011 launch of an informal coalition – the Urban Movements Congress (Kongres Ruchów Miejskich) – comprising urban activist groups from all over Poland. -

The congress was tasked with formulating a programme to provide a common foundation around which urban activists would build their campaigns in local communities. The programme was focused on three main pillars: policies to stem and reverse the growth of socio-economic inequalities and exclusion; sustainable environment-conscious urban development in the interest of all residents; and promotion of direct democracy practices such as social consultations, participatory budgeting and referendums.

On the national level, the congress managed to pressure the Ministry of Regional Development to include some of its policies in its 2012 National Urban Policy (NUP) programme. On the local level, urban activists also managed to reap a number of victories.»With the 2015 elections approaching, the Urban Movement hopes to have an even larger political impact«

In 2011 the mayor of Sopot agreed to implement participatory budgeting in the city. Residents now can decide how to spend 5 million złotys (about 1.2 million euros), or one percent of the municipal budget. Other mayors soon followed suit.

In Łódź, residents decide on how to spend 40 million złotys (about 10 million euros). The mayor of Łódź also invited local activists to advise the city council’s Revitalisation Bureau on specific policies for the socio-economic development of the city. The reason that Łódź became more accepting of the urban movement’s demands was because its previous mayor, Jerzy Kropiwnicki, was removed in a popular referendum in January 2010. The mayors of Częstochowa, Olsztyn, Elbląg, Bytom and Ostróda were also removed in the same manner for introducing policies regarding privatisation and commercial development that went against the will of their electorates.

-

The FUF encourages local interaction and discussion about the murals – raising awareness and interest and encouraging civic pride and engagement within the community. The initiative has made the post-industrial city of Łódź, dubbed the “Manchester of Poland”, one of the most important centres of street art in the world

-

Igor Stokfiszewski is a journalist and activist of Political Critique, an independent sociopolitical organisation operating within Poland and Ukraine.

politicalcritique.org

A slightly longer version of this article first appeared on Aljazeera.com on December 9, 2014 under the title: The Rise of Poland’s Urban Movement. Republished courtesy of Al Jazeera.

The project has now attracted local business and local government investment. Visitors come from all over the world to tour the city streets – because of the street art. But they also stay to learn more about one of Poland’s most striking former nineteenth century industrial centres.

Grassroots victories

The same fate threatened the mayor of Warsaw, Hanna Gronkiewicz-Waltz, but a low turnout at the referendum saved her and she later quickly implemented some of the urban movement’s demands. But the most spectacular achievement of the Polish urban movement in recent months was putting Kraków’s candidacy to host the 2022 Winter Olympic Games to a referendum. To the displeasure of the local authorities, some 36 percent of Kraków’s citizens voted and 70 percent of those said “no” to the games.The Kraków victory incited the formation of a nationwide coalition of 12 socio-political entities affiliated with the Urban Movements Congress to contest the 2014 local elections. The results of the election demonstrated that the movement can translate its grassroots support into electoral victories. With the 2015 parliamentary and presidential elections approaching, the coalition is hopeful that it will have an even larger political impact.

The urban movement has a long way to go in order to occupy a permanent place on Poland’s political map. But its public presence, successful campaigns and increasing social support show that there is a definite shift in Polish people’s socio-political attitudes. There is clearly growing support for sustainable and environmentally conscious development, which aims to level out inequalities and exclusion and usher in effective practices of direct democracy. I

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Less is a bore.«

Robert Venturi

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents