-

Photo: Leena Cho & Matthew Jull

Magazine No. 05

Apocalypse soon!

-

No. 05 - Apocalypse Soon!

-

page 02

cover

-

page 03

Apocalypse Soon!

-

page 04 - 13

Fighting Nature With Nature

Creating resilient urban environments against natural catastrophes

-

page 14

Little Apocalypse

-

page 15

Safety Blast

-

page 16 - 21

In the Photo Booth with...

Geoff Manaugh

-

page 22

Zombie Proof

-

page 23 - 29

We Deserve it

Through the lens of Petrochemical America

-

page 30

Ends of the Earth

Land Art to 1974

-

page 31 - 42

Under Tomorrow's Sky

The speculative futures of Liam Young

-

page 43 - 46

Virtual Memorials

History in 3D

-

page 47

Escape to Space!

-

page 48 - 52

Arctic Paradox

Apocalypse or Eden?

-

page 53 - 54

Bookmarked

-

page 55

Next

Perspectives on Design

-

-

The Mayan calendar predicts that the end of the Fourth World and start of the Fifth will fall on 21 December, 2012: an apocalypse followed by a brand new age – scary, perhaps, but also... exciting.

uncube has taken the occasion of an impending new era to focus on the architecture of catastrophe, the conditions of failure, and the design solutions that prepare us for the end – and of course, what comes after. We hope you savor this issue – you may only have a week to read it!

The Editors

![]()

Cover Photo: Iwan Baan

-

Fighting Nature

Creating resilient urban

environments against natural

catastrophesText: Susannah Drake

With Nature

Damage caused by a fire at Breezy Point in Queens, New York City after Hurricane Sandy. (Photo: Fox News)

-

In the wake of the deaths and terrible devastation to private property and public infrastructure from Hurricane Sandy, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced recently that he would seek 43 billion dollars in federal relief funds to help the New York metropolitan region rebuild in the hurricane’s wake. In the weeks following the storm, many ideas and options have been raised about what to do now, and in the future, to help those in need. It is time for a radical rethinking of urban life to address the realities of climate change on coastal cities.

In the aftermath of the Hurricane Sandy there has been a great deal of speculation about the use of flood gates. Designers and public officials often look to the Dutch for examples of water management technology. This seems sensible given that the Netherlands, a country with around 25 percent of its land area below sea level, employs many innovative strategies such as dykes, dams, and polders to manage seawater intrusion.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Cars are partially submerged in water following heavy flooding by Hurricane Sandy in Belmar, New Jersey, November 1, 2012. (Photo: Michael Reynolds)The fire in Breezy Point destroyed between 80 and 100 houses in the flooded neighborhood. (Photo: Fox News)

-

![]()

![]()

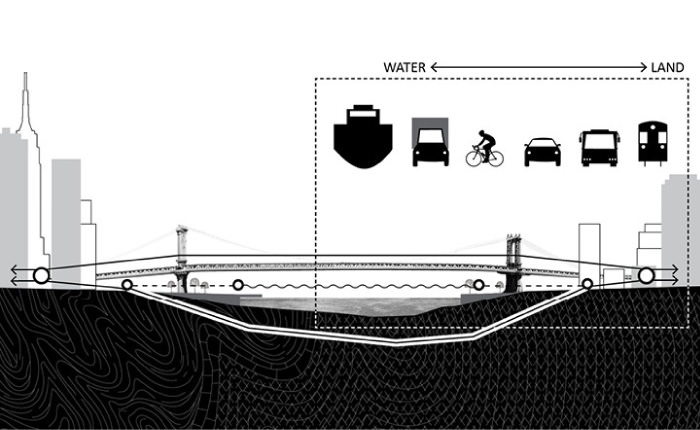

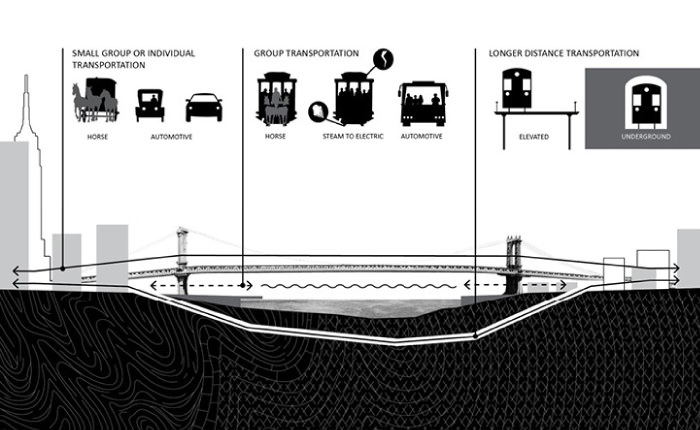

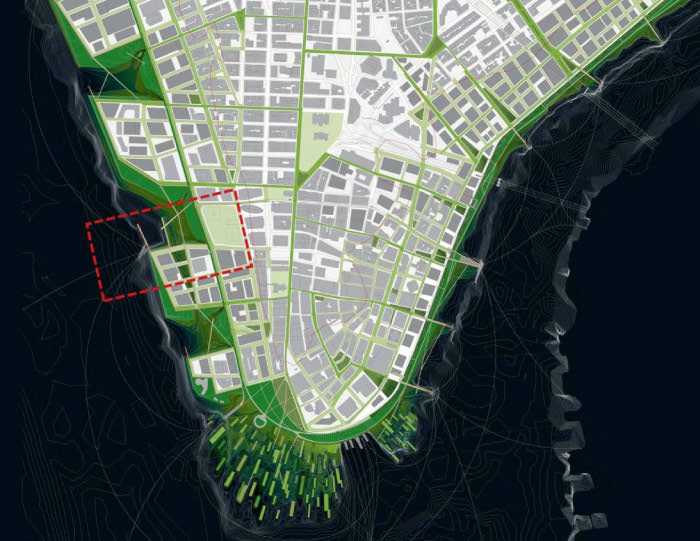

Analysis diagrams by dlandstudio for the exhibition “Glimpses of New York and Amsterdam in 2040,” in which Susannah Drake showed ideas for a Hybrid Urban Base, a new intermodal civic and transportation system. (Image courtesy dlandstudio)

The Dutch strategy of planning for 10,000 years into the future is necessary to protect not only their built environment but also their GDP, 68 percent of which is derived from land that is below sea level. Given the value of physical property in the Northeastern United States and perhaps the even greater value of keeping one of the largest economic engines in the world running, New York needs to radically rethink its approach to protecting its resources. Flood gates, similar to those forming part of the MOSE scheme being constructed in protect Venice, are a simple but expensive solution that the general public may understand and approve of, but their use could trigger a set of extraordinary ecological and socioeconomic impacts down the line. Volatile Infrastructure The term “infrastructure” developed in the World War II era in reference to military logistical operations. In today’s cities, our infrastructure facilitates, enables, and distributes the exchange of goods and services. Advances in technology in the aftermath of the industrial revolution such as the pure engineered solutions of large concrete structures, including storm culverts and sea walls, were seen as superior to the “softer” historical precedent. As was visible in the aftermath of Hurricanes Katrina, Irene, and now Sandy, these inflexible, engineered systems can fail with catastrophic consequences as the severity, frequency, and intensity of storm events increases.

-

It is time to rethink twentieth-century engineering and consider options that can again work in concert with the natural environment.

Understanding how physical geography, ecology, and climate function is critical to the development of new types of infrastructure that are more responsive to the forces of nature. The idea of using natural systems to provide public amenity and health benefit is not new. For example, Frederick Law Olmsted used tidal flows to reduce pestilence and pollution in the Back Bay Fens of Boston in the nineteenth century. Yet Olmsted did not rely solely on plants and fauna to achieve his goals; he employed highly engineered systems, hidden from public view, which improved the effectiveness of his designs without detracting from their beauty.

Olmsted’s strategies, however, could only go so far to manage increased waste. When English plumber Thomas Crapper refined and promoted the flush toilet, he surely had no idea his work would trigger a cascade of events that would lead to the degradation of waterways across the globe some 150 years later. Rapid urbanization in the US in the latter half of the nineteenth century created the need for collective management of sanitary waste in cities. In search of innovation, the US looked to France and Germany, where a new form of infrastructure – the combined sewer – was already being used to manage increased sanitary waste resulting from the ubiquity of the flush toilet. Combined Sewer Outfalls (CSOs) release a combination of surface water runoff and sanitary sewage into our waterways when there is too much effluent for the treatment plants to manage.

New York City, like 772 cities across the US, has a combined sewer system. In New York’s case, in even a light rain, sanitary and storm wastes combine and flow into New York Harbor. Virtually all US cities with combined sewer systems are in violation of the federal Clean Water Act, whose rules,![]() Downtown Manhattan underwater. (Photo: Susannah Drake)

Downtown Manhattan underwater. (Photo: Susannah Drake)»To find solutions to the problems of storm surge and antiquated, inadequate, and unprotected infrastructure, political leaders, planners, and designers need to look to nature for part of the answer.«

-

Flooded Chelsea on Monday night after Hurricane Sandy. (Photo: Susan Hamaker / japanculture-NYC)

-

enforced by the US Environmental Protection Agency and state regulatory bodies, are forcing cities to develop strategies to clean and process storm water runoff. Unlike Hurricane Irene in 2011, Hurricane Sandy was not a small storm.

At the height of the hurricane, the region was flooded by exceptionally high tides and storm surges, putting tremendous pressure on the combined sewers and flushing contaminated waste water — from toilets, storm drains, streets, and factories — into New York Harbor. Even small waterways, like Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal, overflowed their banks, spreading water contaminated with both bacteria and toxic chemicals across residential streets, sidewalks, yards, and into houses and businesses.

Nature is (part of) the answer

In the US we need to look further into the future, taking advantage of the great opportunity to develop new innovations based on our

![]()

![]()

Proposed protective wetlands around the tip of Lower Manhattan from the “Rising Currents: A New Urban Ground” exhibition at MoMA. (Images: dlandstudio)

-

geographic diversity. In New York, highways, train yards, and public housing are often located in flood plains along the post-industrial waterfront, where the land was cheap, available, and in some cases already publicly owned. To find solutions to the problems of storm surge and antiquated, inadequate, and unprotected infrastructure, political leaders, planners, and designers need to look to nature for part of the answer.

The function of barrier reefs, salt marshes, and cypress swamps, depending on the climate of an area, can inspire new models for ecosystem management. Gradual buffered waterfront edges and barrier islands can weaken wave energy, contain saltwater flooding, and make healthier habitats that also help store carbon. Planning for the periodic swells of rivers and streams could well force the relocation of homes, roads, and businesses unless we adapt the architecture (buildings) and landscape architecture (infrastructure and outdoor space) by rethinking how the landscape absorbs water, the materials of construction, the relocation of mechanical systems, and access. Zoning jurisdiction should consider topography so that buildings and infrastructure in flood plains have specialized design. Roads built of porous materials can soak up water, and highway trenches can be covered with parks that clean the air and provide recreation space, and our shorelines could be re-designed with an alternating combination of hard edges to facilitate commerce and softer edges to protect valuable upland real estate. Critical infrastructure below grade should be protected from inundation by saltwater. Whenever and wherever possible, other infrastructure should be relocated above the highest potential flood levels.

As we develop the means and methods for managing increased and more frequent storm impacts, we have a tremendous opportunity, some 40 years after the Clean Water Act became law, to manage the day-to-day loads and the exceptional circumstances with holistic new gray/green»We’ve got to rethink where you build houses, where you build schools, where you build highways and how you build them. We have to redefine our flood plains.«

-

engineered approaches. The USEPA estimates that $94.9 billion will be needed for storm water management and CSO mitigation, to bring cities into compliance with the law. At the same time, over 50 billion dollars is the projected sum needed to rebuild New York City alone. Resources to address these issues should be combined. Need for immediate action to help people displaced by the storm is important, but as we move forward it is critical to assess whether certain sites are suitable for development. Vulnerable areas should be designated as ineligible for mortgages and insurance.

Aggressive long-term planning

We can’t contain nature to the extent believed in the last century; long-term, large-scale planning and actions that reduce our impact on the land, work in concert with natural systems, and enable new types of ecological and socioeconomic exchange are necessary if we are to lessen the impacts of nature’s force. The very survival of this city and all cities that exist at sea level around the

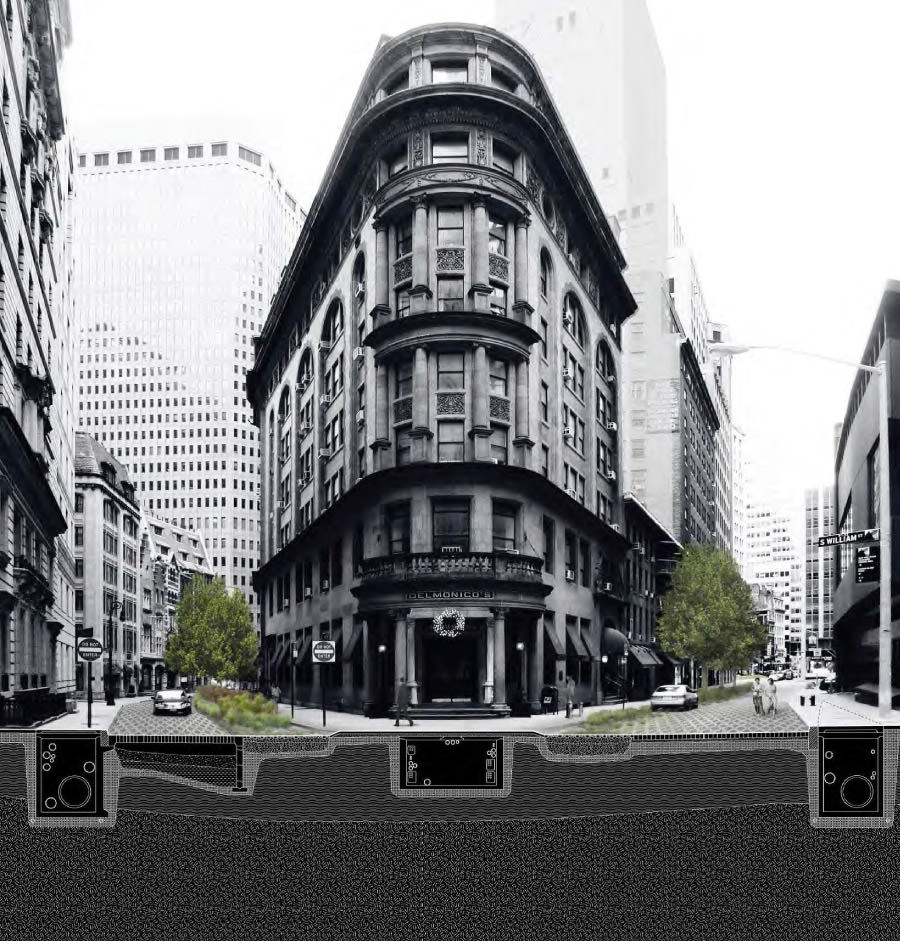

![]() Adapted infrastructure with private and public infrastructure moved under sidewalks, freeing up street surfaces – 28 percent of the city by land area – to be water-permeable surfaces. (Image: dlandstudio)

Adapted infrastructure with private and public infrastructure moved under sidewalks, freeing up street surfaces – 28 percent of the city by land area – to be water-permeable surfaces. (Image: dlandstudio) -

Lower Manhattan in the dark after the Hurricane. (Photo: Iwan Baan)

-

world depends on their becoming resilient to climate change and increasingly numerous and powerful storms. Urban resilience requires an aggressive, multifaceted approach to both the adaptation of existing infrastructures and the development of radical new systems. Moving forward, we must employ a hybrid methodology that manages the force of saltwater storm surges by expanding both engineered and natural softening of select waterfront edges while also expanding our approaches to upland fresh stormwater management.

Mayor Bloomberg and Governor Cuomo have spoken with urgency about our mission. Peter Shumlin, Governor of Vermont, which was devastated by last year’s Tropical Storm Irene, said, “Any objective scientist will tell you that as a result of climate change, we’re going to get more intense storms in New England. We’ve got to rethink where you build houses, where you build schools, where you build highways and how you build them. We have to redefine our flood plains.” We must act now to aggressively design and build pilot projects, test materials, challenge assumptions. We need to create a new natural urbanity.

![]()

![]() Photo: Iwan Baan

Photo: Iwan Baan -

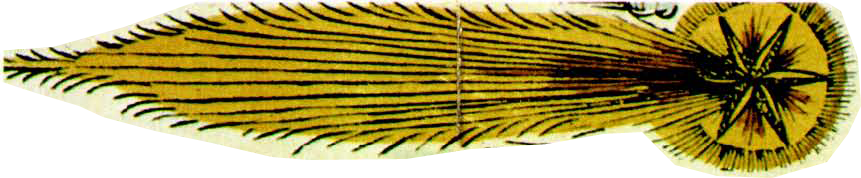

Little Apocalypse

While “little apocalypse” might sound a bit cute, it is the name of an event that certainly wasn’t cute at all. Kiyamet-i sugra was what the giant, devastating earthquake was called, that hit Istanbul in 1509, killing about ten percent of the inhabitants and leaving many more homeless. It is said that the “Big One” will hit Istanbul every 500 years, as the city lies only 10 kilometers from the North Anatolian Fault. At the same time, the region is growing enormously, land prices are high, and thousands of residential buildings have been built too tall, too fast, and too cheaply. Recent studies have indicated that three million houses could collapse and about 300,000 people would die if the “little apocalypse” happens again.

City officials came up with a giant plan to demolish large parts of the most endangered (small-scale, cheap, old) city quarters and rebuild them to be earthquake-safe. Self-demolition before devastation? This might sound like a bold, sensible idea, but most of all the urban renewal schemes bring higher rents, forcing poor people into the distant suburbs. So maybe this is just an excuse for a quick profit before the Big One?![]()

Illustration (details): Hand-colored woodcut of the Istanbul earthquake on 10 May, 1509. The Hagia Sofia and other buildings were heavily damaged, with many fatalities. A comet sighted on 5 March, 1556 remained visible for 12 days. (Printed by Herman Gall in Nuremburg, 1556. Private collection.)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

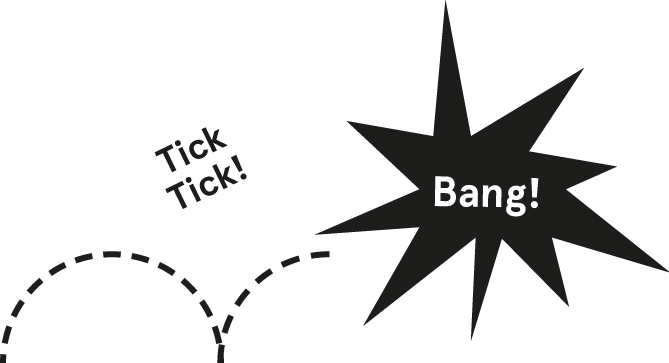

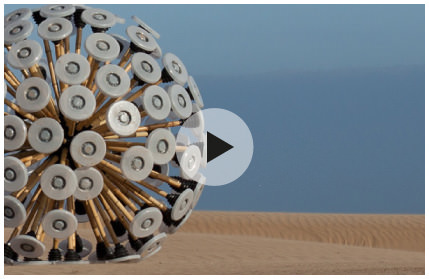

Safety Blast

Growing up in Afghanistan, Massoud Hassani and his friends used to build their own small toys – but every once in a while the wind would carry a toy off to where it couldn’t be retrieved, due to the 10 million landmines spread across the country. Hassani fled Afghanistan at 14, and via Pakistan and Russia reached the Netherlands, where he later started his graduate studies at the Design Academy Eindhoven. Reflecting on his childhood experiences, he invented the Mine Kafon. This beautiful lightweight device is made of 70 bamboo sticks with biodegradable plastic feet that trigger hidden landmines when it rolls over them. It can be rolled around by the wind, and it can also be controlled remotely with the aid of an integrated GPS chip. The project is currently looking for partners to start production.

![]()

![]()

Photo and video: Massoud Hassani.

-

Geoff Manaugh is the author of BLDGBLOG and The BLDGBLOG Book, former senior editor of Dwell magazine and a contributing editor at Wired UK. In addition to lecturing on a broad range of architectural topics at museums and design schools around the world, and freelancing for such publications as The New York Times, Domus, and Abitare, Manaugh has taught at Columbia University, USC, the Pratt Institute, and the University of Technology, Sydney. In August 2011, he became co-director of Studio-X New York.

In the Photo Booth with...

Geoff Manaugh

Who could we invite into our photo booth when the topic is nothing less than the apocalypse? Of course: Geoff Manaugh, one of the most prolific and broad-minded thinkers in the field of architecture – with a special interest in apocalyptic spaces.

Interview by Florian Heilmeyer

![]()

-

Apocalypse isn't only catastrophic destruction. The Greek word also means revelation, epiphany – a new beginning. What would you like to see destroyed before we can start something new?

Well, you’ve caught me on a bad day! Right now, I would say nearly everything should be torn asunder and replaced in a great flash with something new. The world is full of places and people – even new technologies – whose sudden absence would not trouble me.

Of course I don’t spend too much time wishing for a specific building or piece of infrastructure to disappear; I tend to think even the worst of the built environment can be absorbed in some fashion, even if only in a J.G. Ballard-type way, where terrible landscapes – shopping malls, corporate office parks – are recuperated, albeit through a kind of willful psychosis. These landscapes, if examined from the right perspective, can inspire a new, very alien way of thinking – a kind of apocalypse of thought – in which humans encounter something very definitely non-human. Or that was human but has become something else. -

Have you ever been to a place or building that you would call »apocalyptic«?

Straightforwardly: yes, many times, parts of Berlin in the late 1990s, parts of north Philadelphia today, and many abandoned sites and facilities around the world. Just two weeks ago I was at a derelict rocket-fuel production complex in the middle of the Everglades in Florida. It was like Angkor Wat, surrounded by overgrown canals with large subtropical birds in the marshes nearby.

Moreover, I think every site, place, or landscape can be apocalyptic. Like you said: apocalypse means both something that is ending and something new that will be revealed. In this literal sense, a forest on the verge of spring growth is apocalyptic; even animal bodies in the chrysalis stage, or as an embryo, are going through a kind of anatomical apocalypse. -

If we look at recent catastrophes such as the tsunamis in Japan or Chile, or the hurricanes in New York and New Orleans: can design save the world?

A different type of catastrophe comes to mind, actually: the much slower, invisible catastrophe of nuclear waste. I am fascinated – and deeply troubled – by the problem of radioactive waste, although radiation often lacks the instantly compelling media images we see from earthquakes or tsunamis. Nonetheless, it will outlive human civilization by hundreds of thousands, even millions, of years. How to design around this fact is just an extraordinary challenge: something more ambitious than a pharaoh’s tomb, but using insights from materials science. Your project – a kind of cemetery for atoms – needs to outlast entire mountain ranges: architecture designed on the timescale not of cities but of a planet. There are projects being built to avoid or postpone future catastrophes, designed on a scale so vast they can justifiably be called mythological.

I had the surreal pleasure of visiting such a site last summer. My wife and I went down – literally underground – into a specially built salt mine outside Carlsbad, New Mexico. There, the U.S. Department of Energy has been burying low-level nuclear waste, using the geological formation of the salt bed itself, as a permanent repository that should in theory, last hundreds of millions of years. A very sobering place to visit. -

If the world ends on December 21, 2012 where would you like to be for the end-times, either as a safe place or simply a nice final resting place?

It depends how the world will end. The older I get, the more I think I just want to be with my wife somewhere when it happens – maybe ideally in Los Angeles or out in the desert somewhere.

![]()

-

The project description of the Safe House by Polish office KWK Promes doesn’t explicitly mention zombies, but this house is exactly where we’d like to be in the event of a zombie apocalypse – or any kind of major disaster.

On the outskirts of Warsaw, this two-story residence looks normal during the day – but at night (or in the event of an invasion), it can be completely closed up via a mechanical system of moveable cement-bonded wall components. This protects the residents and actually safes energy.

![]()

(...and for those truly terrified of zombie invasion, the 2013 Zombie Safe House Competition will be accepting submissions soon...)

Zombie

![]()

PROOF

-

We Deserve It

![]()

Through the lens of

Petrochemical AmericaPhotographs: Richard Misrach

Text: Jessica BridgerHoly Rosary Cemetery and Dow Chemical Corporation (Union Carbide Complex), Taft, Louisiana, 1998. (All photos: © Richard Misrach)

-

![]()

Cypress Swamp, Alligator Bayou, Prairieville, Louisiana, 1998.

![]()

Swamp and Pipeline, Geismar, Louisiana, 1998.

Sometimes we aren’t very good at seeing the swamp for the marsh grass. Or the gigantic petrochemical industrial network for our Tupperware and cheap gasoline. In Richard Misrach and Kate Orff’s recent book Petrochemical America we are given ample evidence of our deeply embedded love affair with oil. From cancer to imperialistic actions, these horrifying landscapes wrought in the carnage of this relationship have dire implications.

Yes, horrifying in Petrochemical America, Misrach’s moving photographs of “Cancer Alley” along the lower Mississippi in Louisiana are accompanied by Orff’s complex graphics and essays that provide a key to the depth of what we’re really seeing in the still images. It is clear that the “why” behind the images is the stuff of nightmares. At the same time it is hard not to feel like we’re cogs in a fantastic petroleum machine that we tipped into motion, relentlessly polluting, swallowing, and desecrating environments to an unprecedented degree.

It becomes very clear in this book that our moralistic valuation of virgin nature over human development obfuscates responsibility. We’re beyond that binary and into a totalized built environment, a construction of many layers and great complexity – all of our making. -

Any positing that a neutral, pristine condition still exists distracts us from the totalizing scale of the problems. We have fundamentally changed our environment for better or worse, and this book records some of the darker side of this human marvel. After reading Petrochemical America it is hard not to feel like some accountability is in order, that it’s time we accept the larger implications of our relationship with oil.

Through the book, our proximity to these negative aspects of the human project is clear. The close juxtaposition of people’s lives and polluting industry is not new imagery – it has served as a warning since the industrial revolution began, but the scale presented in Petrochemical America is startling. Using Cancer Alley as a lens, Orff efficiently illustrates that this is a small slice of something so large, so complex politically, economically, and socially that it is difficult to determine the extent of the devastation.

![]()

Dow Chemical Corporation At Night, Bonnet Carré Spillway, Louisiana, 1998.

-

![]()

Hazardous Waste Containment Site, Dow Chemical Corporation, Mississippi River, Plaquemine, Louisiana, 1998. -

![]() Sugar Cane and Refinery, Mississippi River Corridor, Louisiana,1998.

Sugar Cane and Refinery, Mississippi River Corridor, Louisiana,1998.![]() Trailer Home and Natural Gas Tanks, Good Hope Street, Norco, Louisiana, 1998.

Trailer Home and Natural Gas Tanks, Good Hope Street, Norco, Louisiana, 1998. -

Petrochemical America

Photographs by Richard Misrach

Ecological Atlas by Kate Orff

Hardcover, 240 pages (plus 24-page insert), 34.3 x 27.4cm

ApertureKate Orff is assistant professor at Columbia University and founder of SCAPE, a landscape architecture studio in Manhattan. Her work focuses on sustainable development, design for biodiversity, and community-based change. Her recent MoMA exhibition, Oyster-tecture, imagined the future of the polluted Gowanus Canal as part of a ground-up community process for an ecologically revitalized New York harbor.

Richard Misrach has a long-standing personal connection with New Orleans and the surrounding region. Destroy This Memory, his latest published monograph, shows a record of hurricane-inspired graffiti left on houses and cars in New Orleans in the wake of Katrina, which won the award for Best Photobook of the Year, 2011 at PhotoEspaña. Other books include On the Beach and Violent Legacies.

That a swamp completely contaminated by Shell Oil can look so lush and beautiful is a shock. Misrach and Orff seem to want to lure us in with this terrible beauty, tracing the lines of how we got to where we are now.

Yet there is a central question that readers must answer: why? Is the information a call to arms? Is the book a toolbox for action, an index of possibility? In feeling the guilt and disgust about what we’ve done do we then feel like we’ve atoned through emotional gymnastics? In that case the book is effective. But after seeing what we’ve done, it is difficult to rouse anything resembling a call to arms: “the humans are coming, the humans are coming!” Shame on us for what we’ve done, we deserve what’s coming next. It’s up to you to do something about it.

![]()

![]() Night Fishing, near Bonnet Carré Spillway, Louisiana, 1998.

Night Fishing, near Bonnet Carré Spillway, Louisiana, 1998. -

Exhibition: “Ends of the Earth. Land Art to 1974”

11 October 2012 to 20 January 2013

Haus der Kunst, Prinzregentenstrasse 1, 80538 Munich

www.hausderkunst.deCatalogue: Ends of the Earth. Land Art to 1974, edited by Philipp Kaiser and Miwon Kwon, 264 pages, Prestel Publishers 2012, 49,95 Euro

www.randomhouse.de

ENDS OF THE EARTH

Land Art to 1974

Text: Sandra Hofmeister

There was a time when artists created lightning fields and giant stone spirals, placed oversized installations and massive structures in salt lakes and deserts. But it is Hans Haacke’s Grass Grows from 1969, a small hillock of meadow, that is at the entrance to the Haus der Kunst in Munich and begins the exhibition Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974. With nearly 200 works by more than 100 artists, the show curated by Philipp Kaiser, is a comprehensive overview of an artistic position that rejected the institutional limits of the art system. From the mid-1970s onwards, the common ground of Land Art began to diverge in distinct movements such as conceptual art, happenings, performances, and Arte Povera. Whether experimenting with earth or stones, investigating regional landscapes or the globe itself, artists like Richard Long and the neo avant-garde group Superstudio understood the planet as their medium and made their work part of it. Photographs and models, installations and videos produced by the artists are all displayed in the exhibition. The most astonishing aspect of the curators’ view is the plurality of locations and mindsets. Thus the show makes evident that Land Art was not only a North American but an international phenomenon, with protagonists all over the world.

![]()

Heinz Mack: “Tele-Mack”, film still, 1968. (Image courtesy Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland GmbH and Mack Archive, © 2012 Artists Rights Society, New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn)

-

![]()

![]()

U n d e r

Tomorrow's

SkyThe

speculative

futures of Liam YoungText: Julia Albani

Kate Davis and Liam Young, leaders of the Unknown Fields Division, standing on a rooftop in Chernobyl. (Photo: Johnathan Gales)

-

In 1979, Kenneth Gatland and David Jefferis published the Usborne Book of the Future – A Trip in time to the year 2000 and beyond, a chronicle of the future with flying cars, space ships, moon beams, robots. The visions within were readings of the culture and time in which they were written rather than prophetic images of tomorrow, creating a surprisingly encyclopedic insight into the dreams and anxieties of the 1970s and 80s.

In the same year that the book came out, Liam Young was born in Australia. Usborne would later become his favorite book, and today, conjecturing yesterday’s futures likewise defines his agenda. Prediction of the future is only one side effect of science fiction, says Young, since it’s really a mode of exploring the present. Young imagines future worlds as a means to understand the present anew. To him, the future is constantly being created. It’s a verb, not a noun.

![]()

![]()

Unknown Fields is a nomadic studio organizing annual expeditions “to the ends of the earth exploring forgotten landscapes, alien terrains and obsolete ecologies.” In 2011 they explored the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. (Photos: Neil Berret)

-

![]() This picture sees the Unknown Fields Division one kilometer below the ground exploring an Australian gold mine in 2010. (Photo: Oliviu Lugojan-Ghenciu)

This picture sees the Unknown Fields Division one kilometer below the ground exploring an Australian gold mine in 2010. (Photo: Oliviu Lugojan-Ghenciu) -

...and in the winter of 2011, Young, Davis and their students travelled to the Arctic Ocean in Alaska, inspired by a Kurt Vonnegut quote: “I want to stay as close to the edge as I can without going over. Out on the edge you see all kinds of things you can't see from the center.” (Photo: Christina Seely)

-

Trained as an architect, Young worked for a number of high-profile offices including Zaha Hadid Architects and LAB Architecture Studio, before escaping the system to become an independent urbanist, futurist, designer, critic, and curator. In 2008 he founded the think-tank Tomorrow’s Thoughts Today. He is based in London, when not on expeditions exploring unreal and forgotten landscapes, alien terrains, and obsolete ecologies. He fights against the torrent of professional conservatism in the urban and regeneration industries and seeks to revive dormant ideas as new sources of inspiration from para-disciplinary fields. These pursuits often lead to reappraisals of dysfunctional systems, engaging aspects of pop, pulp and the vulgar.

Together with the designer, writer, and educator Kate Davies, Young navigates as The Unknown Fields Division, a nomadic design studio that maps complex and contradictory realities of the present as a site of strange and extraordinary futures, either through physical expeditions or the design of speculative projects. Young has witnessed the climate change catastrophes of Alaska to the arctic circle to the oil fields of the Amazon. He’s led an expedition from Chernobyl Exclusion Zone through the Ukraine and the oil fields of Azerbaijan to the rocket launch pad of Kazakhstan’s Baikonur Cosmodrone. In the shadows of nuclear disaster, he surveyed the irradiated wilderness and bore witness to a sobering apocalyptic vision of the past.

By the end of this year, Young and his students will make it to the Mayan ruins to await the end of the world. In this expedition, he will ponder the rise and fall of cities and civilizations, investigating the cultural and technological infrastructures that underpin their prosperity and collapse. Though admittedly seduced by the sensationalism of the apocalypse, he is sure that 21 December, 2012 will be just another day. What he finds interesting about the apocalypse is the way that its myths have been engineered by![]() Under Tomorrow’s Sky is a “speculative” city model developed by Liam Young together with a think-tank of scientists, technologists, authors, and illustrators.

Under Tomorrow’s Sky is a “speculative” city model developed by Liam Young together with a think-tank of scientists, technologists, authors, and illustrators. -

![]()

Early in the design process, artist Hovig Alahaidoyan translated fragments of the think-tank’s discussions into a set of sketches: here, he depicted how the city’s inhabitants scavenge on the mudflats in the shadow of heavy industry.

-

![]()

Under Tomorrow’s Sky ranges from utopia to dystopia. This picture is part of a series by artist Daniel Dociu’s series ‘Urban Tectonic’ where he shows his visions of this future city.

-

media apparatuses – hyped up, for example, to support the promotion of the John Cusack movie 2012. The way cultural fictions are designed is fascinating and relevant for speculative architects. Although fabrications, these fictions have real effects.

Young, who was named in 2010 by Blueprint magazine one of 25 people who will change architecture and design, explores fantastic, perverse and underrated architectures by inviting mad scientists, literate astronauts, digital poets, speculative gamers, mavericks, and luminaries to collectively develop imaginary places and narratives. This spring, as part of his program Under Tomorrow’s Sky, he initiated a design project for a speculative city with a group of scientists, technologists, authors, and illustrators like Bruce Sterling, Rachel Armstrong, Geoff Manaugh, and Nicola Twilley. The exhibition featured a room-sized model along with behind-the-scenes work from the think-tank. In online and live discussions held over several

months, the invited practitioners came together to design this future city and discuss the possibilities of emerging biologies and technologies. The result was not familiar dystopian visions of the future, but one of post-capitalist urbanity filled with optimism and joy. The model was used as a backdrop for animated films and a stage set for a collection of stories and illustrations, and audiences could contribute their own narratives to the city through a series of workshops.

Under Tomorrow’s Sky gave birth to a work called Electronic Countermeasures, which expresses the fact that today we are often closer to our virtual communities than we are to our real neighbors. Young designed and manufactured a flock of modified quadrocopters that form their own place specific, local, wi-fi community and pirated file-sharing network. As part of Eindhoven’s GLOW Festival 2011, the fleet of drones performed a balletic aerial choreography as they waited for passers-by to interact with them.

![]() Electronic Countermeasures in 2011, saw a fleet of interactive drones hovering around Eindhoven in the Netherlands.

Electronic Countermeasures in 2011, saw a fleet of interactive drones hovering around Eindhoven in the Netherlands.![]()

-

The more people interacted with the drones the more excited and illuminated the flock became, like living mobile infrastructures with endearing behaviors. For Young, technology and nature are not in opposition to one another; and he invites us to rethink default conservationist positions and to explore design strategies for a new kind of technological wilderness.

In his recent Singing Sentinels exhibition and the accompanying performance “Silent Spring: A Climate Change Acceleration,” Young released 80 live canaries into the New Order exhibition space at the Mediamatic Gallery in Amsterdam. As a “pollution DJ,” he flooded the gallery with CO2, altering the air mixture to replicate predicted atmospheric changes of the next 100 years. The birds became an ecological warning system, living in the space and providing audible feedback on the state of the atmosphere. One could hear the canary song subtly shift and eventually silence, as the birds sang an elegy

![]() If you like animals maybe you shouldn’t read this: the exhibition/performance “Singing Sentinels” in Amsterdam featured 80 live canaries and a gas cylinder...

If you like animals maybe you shouldn’t read this: the exhibition/performance “Singing Sentinels” in Amsterdam featured 80 live canaries and a gas cylinder... -

![]()

Liam Young, wearing a gas mask and calling himself a “pollution DJ”, flooded the space with more and more CO2, creating the atmospheric conditions that are predicted for Earth in 2100. Watch the video.

-

for our changing planet. With Geoff Manaugh and Tim Maly, Young published the book A Field Guide to Singing Sentinels: A Birdwatcher’s Companion, with illustrations from comic illustrator Paul Duffield.

Writing the future’s history, Young’s contribution as an explorer and visionary is not through predictions but through critical engagement of contemporary issues at stake. To him, architecture is the link between the cultural, environmental, political, and technological, synthesizing complex factors to stage brave new scenarios today. We can only speculate as to what he’ll come back with from Central America after the apocalypse. Most probably it will be something we haven’t seen before.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The rising CO2 level in the exhibition turns the canaries into an ecological warning system: “We hear the canary song subtly shift, as they sing an elegy for a changing planet”. With binoculars and the “Birdwatcher’s Guidebook to Singing Sentinels”, visitors were able to spot and identify these Specimens of Unnatural History. (Illustrations: Paul Duffield)

-

Virtual Memorials

History in 3D

Text: Elvia Wilk

-

It doesn’t take an apocalypse to wipe out a building. Demolition happens all the time as demographics shift, economic tides ebb and flow, and varying political agendas come to the fore. Removal is often a more emphatic political tool than construction is, and demolition can be a divisive and painful process, striking at the nerve centers of cultural heritage, community unity, and spatial ownership. Whether loss results from human action or natural catastrophe, preserving the memory of a place is a complex endeavor. “History for everyone has become reduced to the evidence of a photograph,” wrote geographer David Harvey in 1989. Today, history’s representation is fleshed out far beyond the flat image – it’s become a multi-dimensional, virtual construction. Does use of digital renderings, virtual reality, and hi-tech mapping systems enrich historical memory or reduce it further? Temporary Memorial Project for Jobbers’ Canyon In 1989, 24 buildings in a district of downtown Omaha, Nebraska known as Jobbers’ Canyon were demolished to make way for ConAgra’s sprawling new executive headquarters. Occupying six city blocks along the Missouri River, the masonry and timber-frame architecture epitomized early-1900s midwestern Renaissance Revival style (yet to Charles Harper, the chief executive of ConAgra at the time, they just looked like “some big, ugly red brick buildings"). Despite protests from citizen’s groups and historic organizations, Jobbers’ Canyon was flattened in the name of economic progress –the largest site in the US National Register of Historic Places ever lost. Artist Nicholas O’Brien has digitally re-composed ten of the district’s buildings using products manufactured by ConAgra Foods. In a series of simulated, slow-motion explosions, each building is re-demolished. O’Brien’s project, A Temporary Memorial Project for Jobbers’ Canyon built with ConAgra Products, questions the role of the memorial, hovering between historical

![]()

![]()

Artist Nicholas O’Brien digitally reconstructed ten demolished buildings in Omaha, Nebraska, from ConAgra products - the company that tore down the buildings. In this animation, a turn-of-the-century warehouse building by architect Thomas Rogers Kimball is rebuilt using “Crunch ’n Munch”, a ConAgra brand of caramel-coated popcorn and peanuts. (Video: Turbulance.org )

-

re-creation and prescient contemporary interpretation. As the result of a recent buyout in November 2012, the ConAgra corporation is poised to become the largest packaged food business in the US. Watching O’Brien’s cereal-box buildings collapse again and again is like watching the past collapse into the present. Press replay: the repercussions continue to cascade down. WeltraumpalastA more recent, prominent case of demolition with great political ramifications was the 2008 removal of Berlin’s iconic Palast der Republik (Palace of the Republic). The former parliamentary house of the GDR was itself built atop the bombed-out ruins of the Berlin City Palace, the former seat of the Prussian Monarchy. A symbol of socialism mounted atop a flattened symbol of imperialism, the palace’s destruction in the name of aesthetic progress and unity could not have been more heavily-laden.

For the project Weltraumpalast, Prof. Stefanie Bürkle (in collaboration with the German Aerospace Center) used an Eyescan panoramic camera to scan the interior space of the palace before its destruction, creating a 360-degree virtual footprint to outlast the architecture. In conjunction with the stereo imaging, an image of the building’s façade was printed as a pattern wallpaper, replicating the building’s exterior “skin” to be applied on any surface in the city.

In 2008, Berlin’s Bundestag claimed that the palace was too much of an eyesore and a symbol of political division to remain a worthwhile piece of architecture. In 1989, ConAgra officials argued that the economic revitalization the company would bring to Omaha trumped the importance of historic preservation. What is preservation really worth? What is lost along with a place?![]()

-

![]()

Tuvalu Visualization Project Tuvalu is the fourth-smallest country in the world, with a population just over 10,000. Due to accelerating climate change, its land mass is slowly sinking into the Pacific Ocean – in the next 100 years, it may submerge too far to be habitable. Tuvalu Visualization Project, a joint research project of NPO Tuvalu Overview and Hidenori Watanave Loboratory at Tokyo Metropolitan University, has since 2008 attempted to document both the island’s diminishing geography and its endangered population.

The Tuvalu Visualization project archives snapshots of Tuvalu’s residents and geography, wich are tagged to Google Earth markers to provide a virtual tour of the island. Via a dialogue box, users can read about each resident and transmit messages to them online. The work is in some sense a preemptive memorial, a documentation in real-time that anticipates the island’s loss while providing a dynamic exchange with its present. By illustrating the intrinsic cultural links between the people of Tuvalu and their landscape, the visualization also connects the ever-more isolated Tuvaluans with the rest of the world, forging empathic links between remote populations through virtual means. Rather than typical news channels that foreground disastrous events on a quantitative scale, this aims for a different type of accuracy: that of human experience.

History is a creation of the present – a photograph is no less a simulacrum than a 3D rendering is. Memory is not about factual accuracy, it’s about the ability to situate oneself in the present through identification with the past. Approaches such as the Temporary Memorial Project for Jobbers’ Canyon, Weltraumpalast, and Tuvalu Visualization construct imagined, virtual connections in tandem with physical exactitude, visualizing the invisible architectures of political implications and human relationships for a complete and nuanced memorial of the lost.![]() (ew)

(ew)![]()

The Tuvalu Visualization Project archives the disappearing island of Tuvalu and its 10,000 inhabitants through photographic portraits of both people and places attached to GPS markers on Google Earth. (Video: NPO Tuvalu Overview + Hidenori Watanave Lab at Tokyo Metropolitan University, supported by Photon, Inc.)

-

Escape to

Space!Why bother about any apocalypse when we can just escape to space? This is “Spaceport America,” the world’s first commercial, private spaceport. Unfortunatly Spaceport has just postponed the launch of their first space flight for wealthy privateers and wannabe-spacetourists until 2013. Depending on how this Mayan prediction turns out in the end, that could be just a bit too late…

![]()

(Photo: Nigel Young / Foster + Partners) -

![Arctic Paradox Arctic Paradox]()

Apocalypse or Eden?

Text: Leena Cho & Matthew Jull

All photos by Leena Cho & Matthew Jull in Barrow, Alaska.

-

![]()

![]()

The transformation occurring in the Arctic is a highly insidious, slow-moving shift caused by a progressive modification of global temperatures. Such changes in the arctic implicate fundamental re-configurations not only at a local scale but that of the continental and geologic. For instance, the rise of sea levels due to melting ice caps and glaciers; the re-orientation of global weather patterns; the release of methane gas due to thawing permafrost; receding coastlines; and extraordinary migration and extinction of species are only a few examples of the changes that have already begun accelerating. The chronic and profound nature of this change is beyond the parameters of human control. Accordingly, we are faced with fear, uncertainty, and awe of the unknown – perhaps even a return to something resembling the Middle Ages – all permeate through the deep soils of our political, economic, cultural, and spiritual conscience. The significance of human influence upon the earth’s ecosystem in recent centuries has further constituted a new geological era for its lithosphere: the Anthropocene. Combined with insatiable technological advancement and mystical prophesies, the world we live in has become a site of speculation about planetary apocalypse, where ordinary lives collide with ever-increasing dimensions of natural forces and the ghostly traces of our own artifacts.

-

![]()

-

Yet perhaps one man’s apocalypse is another man’s Eden. As one person preparing for doomsday said: “When (sh)it hits the fan, my family’s plan is not to survive but to sur-thrive.” For many, the Arctic is the new frontier – a realm of eternal sunsets, magical aurora and untouched landscapes, now finally becoming unlocked from the grip of deep freeze. Polar romanticism and adventures are resurging, as evidenced by rising eco-tourism. And yet no arctic species will profit from the unfrozen north as much as the one causing it to melt: humans. As the tundra retreats northwards, large areas of the Arctic will become suitable for agriculture; plant growth will increase, significantly prompted by early arctic spring; precious minerals such as gold, zinc and iron will be mined; exploration licenses for oil and gas are already being issued across the region; global shipping routes are gravitating towards the melting, navigable Arctic Ocean; and this consequence of climate change will even allow more hydrocarbons to be extracted and burned. To this end, the “cold rush” of the twenty-first century is on its way to maturation, creating an unprecedented new stratum of opportunities, wealth and human experience.

To an apocalyptic disciple, this arctic paradox – death and re-birth, the misery and the ecstasy of the north – could be one of the obvious symptoms of the end of the world. Forget the Middle Eastern conflict: the Polar War involving eight arctic states might be nearing. The latitude of the Arctic Circle (66° 33′ 44″) might be the new contested border for immigration and patrol. Regardless of where one stands, the transformation of the north is one that is radical and irreversible. Its fate is a schizophrenic uncertainty.![]()

![]()

-

The White Review

Current Issue: No. 5

Edited by Benjamin Eastham and Jacques Testard

188 pages, Softcover, 240 x 165mm, EnglishSan Rocco

Issue 05: Scary Architects

Edited by Matteo Ghidoni

176 pages, Softcover, 230 x 170mm, English

![]()

![]()

If your definition of an architecture magazine is that it should deliver the latest, glossy, hi-res images of the latest crazy buildings around the world, San Rocco is definitely not for you. This one is about heavy thinking and theory and San Rocco unashamedly celebrates this fact: in strict black and white, without almost any imagery at all, your mind can focus on the texts – which is necessary, because contributions range from the straightforward to the very complex and back again. Published twice a year with topics like “Mistakes,” “Scary Architects,” and “Innocence,” its 200 pages ensure you’ll hardly be finished with one issue before the next one comes out... and thanks to its handy size you can always carry the latest San Rocco around with you – for whenever your brain gets hungry. (FH)

The White Review is a quarterly arts publication printed on the highest-quality paper possible. And the content – for once – matches the presentation: great writing meets a diverse range of styles and subjects inside. With a team of pragmatic young editors, a heavy-hitting editorial board, and a deep commitment to print journalism TWR, now in its fifth edition, continues to deliver insightful coverage of urbanism, poetry, photography, fiction – and all the small beautiful and terrible things that make life as complex and rich as the custom marbling of its endpapers. Limited editions of 1000. (JB)

![]()

-

CLOG: RENDERING

August 2012

Edited by Kyle May, Julia van den Hout, Jacob Reidel, Archie Lee Coates IV, Jeff Franklin

160 pages, Softcover, 215 x 140mm, English

![]()

For those of us who see more sexy architecture online than in person, renderings of buildings have become a standard form of architectural documentation alongside the photograph. The catch, of course, is that the rendered image often documents the building before it is built, or serves as a stand-in for something that never will be. In the always-impressive CLOG magazine’s August 2012 issue “Rendering,” the title topic is rendered in full and from every angle: from pre-computer “renderings” like Mies van der Rohe’s drawings of his unbuilt Friedrichstrasse skyscraper, to an interview with renowned renderers at Luxigon and MIR, CLOG’s multifaceted take on the rendered image unfolds in a beautifully-planned issue of bite-size texts punctuated by fascinating infographics and, of course, plenty of renderings. (EW)

![]()

![]()

-

Next Issue

Perspectives on Design

uncube will be back in January (fingers crossed) with Issue No. 06: Perspectives on Design. We’ll meet the British interior designer Sevil Peach to learn about an appropriate space for tea, and architect Michael Maltzan will talk about his hometown, Levittown, and his new home, Los Angeles. Vitra’s chairman Rolf Fehlbaum discusses his close working relationship with Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec brothers and we’ll drag MoMA’s architecture curator Pedro Gadanho into a New York photo booth to talk about his recent 9+1 exhibition. We can’t wait to see you back in January 2013 ...

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Architecture starts when you carefully put two bricks together. There it begins.«

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents

Downtown Manhattan underwater. (Photo: Susannah Drake)

Downtown Manhattan underwater. (Photo: Susannah Drake)

Adapted infrastructure with private and public infrastructure moved under sidewalks, freeing up street surfaces – 28 percent of the city by land area – to be water-permeable surfaces. (Image: dlandstudio)

Adapted infrastructure with private and public infrastructure moved under sidewalks, freeing up street surfaces – 28 percent of the city by land area – to be water-permeable surfaces. (Image: dlandstudio) Photo: Iwan Baan

Photo: Iwan Baan

Sugar Cane and Refinery, Mississippi River Corridor, Louisiana,1998.

Sugar Cane and Refinery, Mississippi River Corridor, Louisiana,1998. Trailer Home and Natural Gas Tanks, Good Hope Street, Norco, Louisiana, 1998.

Trailer Home and Natural Gas Tanks, Good Hope Street, Norco, Louisiana, 1998. Night Fishing, near Bonnet Carré Spillway, Louisiana, 1998.

Night Fishing, near Bonnet Carré Spillway, Louisiana, 1998.

This picture sees the Unknown Fields Division one kilometer below the ground exploring an Australian gold mine in 2010. (Photo: Oliviu Lugojan-Ghenciu)

This picture sees the Unknown Fields Division one kilometer below the ground exploring an Australian gold mine in 2010. (Photo: Oliviu Lugojan-Ghenciu) Under Tomorrow’s Sky is a “speculative” city model developed by Liam Young together with a think-tank of scientists, technologists, authors, and illustrators.

Under Tomorrow’s Sky is a “speculative” city model developed by Liam Young together with a think-tank of scientists, technologists, authors, and illustrators.

Electronic Countermeasures in 2011, saw a fleet of interactive drones hovering around Eindhoven in the Netherlands.

Electronic Countermeasures in 2011, saw a fleet of interactive drones hovering around Eindhoven in the Netherlands.

If you like animals maybe you shouldn’t read this: the exhibition/performance “Singing Sentinels” in Amsterdam featured 80 live canaries and a gas cylinder...

If you like animals maybe you shouldn’t read this: the exhibition/performance “Singing Sentinels” in Amsterdam featured 80 live canaries and a gas cylinder...