-

Magazine No. 31

Poland

-

No. 31 - Poland

-

page 02

Cover

Poland

-

page 03

Editorial

-

page 04 - 05

Teatr Szekspirowski

Gdańsk

-

page 06 - 07

Muzeum Śląskie

Katowice

-

page 09 - 18

Bread and Circuses

Iconic architecture in post-communist Poland

-

page 20

Light Relief

Warsaw's neon heritage

-

page 21 - 27

Shipyard

Michał Szlaga's loving, melancholic portrait of Gdańsk

-

page 28

Mountains for Warsaw

Imaginative urban waste re-use

-

page 29 - 30

Filharmonia Szczecin

Szczecin

-

page 31 - 32

Akademia Sztuk Pięknych

Wrocław

-

page 33

Manhattan on the Odra

Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak’s flats in Wrocław

-

page 34 - 41

We, the Citizens

The rise of the Polish urban movements

-

page 42 - 43

Muzeum Sztuki i Techniki Japońskiej Manggha

Kraków

-

page 44 - 45

Stadion Miejski

Wrocław

-

page 46 - 53

The Eighth Sister

Warsaw’s Palace of Culture and Science: white elephant or national treasure?

-

page 54

Billboard Brutal

The longest billboard in Poland

-

page 55 - 59

Studio Rygalik’s

Focus on Polish design

-

page 60

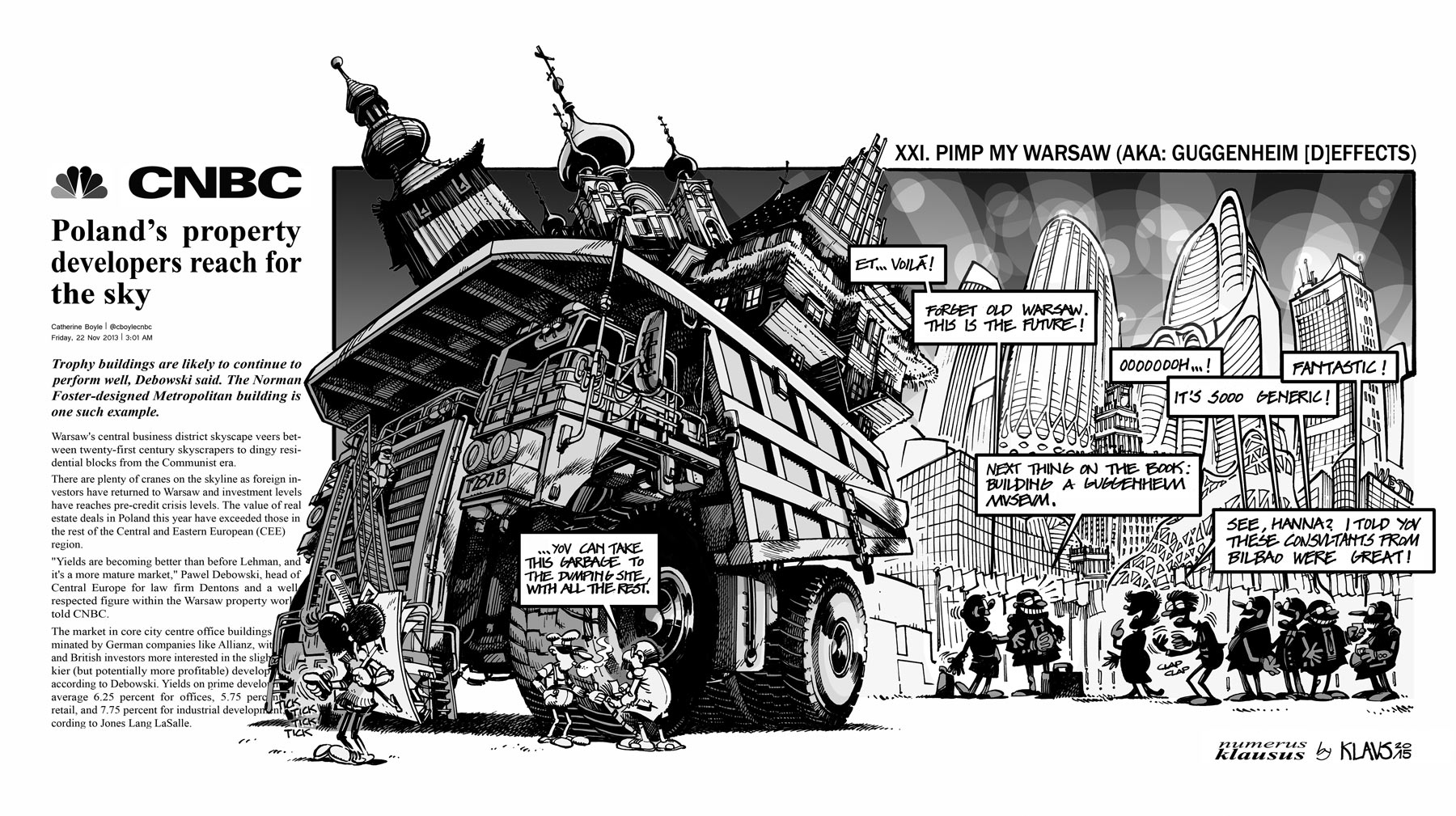

Klaustoon

XXI. Pimp my Warsaw

-

page 61

Next

Expotecture

-

-

uncube's editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer, Rob Wilson and Elvia Wilk; editorial assistance: Fiona Shipwright; graphic design: Lena Giavanazzi, graphic assistance Madalena Guerra. uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online portal covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

![P]() ost-War, post-industrial and post-communist, Polska has certainly had its fair share of struggles and identity issues. But the past decade has seen a land best known for its industrial powerhouses turning instead to the production of cultural capital as a huge wave of investment in cultural infrastructure hits almost every Polish city.

ost-War, post-industrial and post-communist, Polska has certainly had its fair share of struggles and identity issues. But the past decade has seen a land best known for its industrial powerhouses turning instead to the production of cultural capital as a huge wave of investment in cultural infrastructure hits almost every Polish city.

So this month uncube hitched a ride east on the Berlin-Warszawa-Express to travel a land where grassroots activists are challenging mainstream politics and developers are vying with EU funding to create a whole new architectural landscape – one on which opinion in the country is sharply divided.Special thanks to Polnisches Institut Berlin for their support.

Front cover illustration: Damian Nowak, Parastudio*

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Teatr

SzekspirowskiArchitect: Renato Rizzi, Venice

Local Architect: Q-Arch, Gdańsk

Location: Gdańsk

Client: Gdański Teatr Szekspirowski

Opening date: 19 September 2014Photo: Rafal Malko

-

Renato Rizzi was born in Rovereto (Italy) in 1951. He graduated from the IUAV in Venice in 1977 and worked with Peter Eisenman from 1984-1992 (projects included Romeo and Juliette for the Venice Architecture Biennale, La Villette in Paris, the Tokyo Opera House, and the City of Fame in his birthplace Rovereto). Returning to Venice he dedicated himself to research and theory of architecture, teaching at the IUAV ever since. He has continued to contribute to international competitions.

![]()

![]()

Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, English actors regularly visited the prospering harbour city of Gdańsk to stage plays, including dramas by a certain William Shakespeare. In the 1630s the city even built a theatre school to host them. Yet the tradition ended and the building was lost.

In the 1990s these traditions were resurrected, and in 2005 an international competition was held for a new Shakespeare theatre on the old site, by then a parking lot, in a project backed by 70 percent EU funding.. Outside, the new building is a grim and dark fortress of culture surrounded by its own city wall: windowless and almost six metres high, with only two gates granting access. Even the security cameras are painted black.

Yet inside a warm composition of rooms, white colours, stone handrails and lots of wood welcomes the audience. It’s a perfect theatre machine with moveable lighting, platforms and seating, able to accommodate almost every kind of play or event: a “Fun Palace”, surrounded by wooden galleries, and with a roof that can be spectacularly opened in two giant flaps. Even Prince Charles attended the opening, though what he thought of the design by Italian architect Renato Rizzi is not recorded. I (fh)Gif: model by Renato Rizzi; Pro.Tec.O, Pool Engineering; panorama photo: Rafal Malko. Interior and exterior photos: Jakub Certowicz

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Muzeum Śląskie

KatowiceArchitect: Riegler Riewe Architekten

Location: Katowice

Client: Muzeum Slaskie Katowice

Completion date: 2014Photos: Paolo Rosselli

-

Riegler Riewe Architekten, was originally founded in 1987 in Graz, Austria by Florian Riegler and Roger Riewe, and have since opened offices in Katowice and Berlin. Buildings have included the Trade Fair Hall Graz (2008) and the Museum im Palais, Graz (2011), and the practice is currently working on projects in Austria, Switzerland, Italy and Germany, including the Med. Campus Graz and the adaption and renovation of the St Agnes Cultural Centre in Berlin.

rieglerriewe.co.at

![]()

The new Silesian Museum in Katowice, southern Poland, is designed to reflect the complex history of the Upper Silesia region. Due to open in June 2015‚ it also represents the final stage in a set of cultural projects initiated by the local authorities that help bridge a major six-lane highway that splits the city in two. Seen from Katowice’s centre the museum appears as a series of frosted glass cubes, separated by greenery with an old brick mine behind.

According to the Museum’s architects – Graz-based studio Riegler Riewe Architekten – retaining views to the existing mine was a key factor in the design of the new building, which places a large part of its facilities underground. This move also nicely references the fact for visitors that for centuries the fortunes of Upper Silesia have been mainly based underground – in its coal mines. Here the sunken spaces are topped with the cubes that provide daylight, ventilation and access, whilst the largest contains the museum’s offices and administration. I (Roman Rutkowski)

-

![]()

Iconic architecture in post-communist Poland

Text by Agata Pyzik, illustrations by Dagmara Berska, Parastudio*

-

Polish critic and author Agata Pyzik questions the value of current prestige projects in Poland and says that by looking West, the country is searching in the wrong direction for its architectural future.

![]()

Among the countries of the former Soviet Bloc, Poland emerged as relatively privileged and successful following the fall of communist rule, with no civil wars or major ethnic conflicts, and a national unemployment rate that may have been high but was certainly not catastrophic – especially compared to the various republics from the erstwhile USSR. In fact, Poland always belonged to the elite of post-communist countries, rewarded for its fervent anti-communism and willingness to embrace western standards, evidenced by its early membership not only of NATO, but also of central-European associations such as the so-called Visegrad Group (together with Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary). In line with this trajectory, it was among the first wave of formerly communist states to join the European Union in 2004.

Even today, as Europe finds itself in one of its greatest financial crises, Poland still looks in comparatively good shape, thanks both to the national debt cancellation of the early 1990s but also to an unexpectedly privileged position. For while any monetary problems are kept at bay with no small assistance from EU subsidies, the country still remains outside the increasingly shaky Eurozone.A new wave of cultural icons

One clearly visible aspect of Poland’s post-communist success is a huge wave of newly built infrastructure and architecture. These include a much-vaunted new network of highways (the building of which has been at the expense of a slower, rather less-successful renovation of the rail system) and the tendency to view modernisation as straightforwardly proportionate to the number of new “iconic” buildings.

![]()

-

![]()

-

This has led to a huge boom of new museums. In the last decade Warsaw alone saw the opening of three new buildings: the controversial Museum of the Warsaw Uprising by architect Wojciech Obtułowicz in 2004, glorifying a failed uprising bloodily defeated by the Nazis; the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, designed by Finnish architect Rainer Mahlamäki, which was finally completed in 2013; and the Copernicus Science Centre in Warsaw by RAr2 Architecture Laboratory in 2010. Add this to a slew of other cultural buildings from Kraków to Toruń to Gdańsk and beyond.

The boom, which started during the reign of a nationalist right wing party Law & Justice, had a lot to do with former President Lech Kaczyński’s initiative to build new cultural institutions. Despite the ideological war between the right wing and liberals that emerged with new intensity around that time, he equally supported initiatives unconnected with the line of his party.»such prestige projects are a late hiccup of the bilbao effect«

![]()

But beyond public cultural buildings, recent aspirational architecture in Poland has also taken the form of investor buildings such as office towers and luxury flats, including a cluster hailed as the “Canary Wharf” of Warsaw and various high-rises in Gdynia and Wrocław, along with dozens of other private residences and private museums belonging to millionaires. These include the European Krzysztof Penderecki Centre for Music (DDJM Architects, 2013) in rural Lusławice, and the Stary Browar art and shopping centre in Poznań (Studio ADS, 2003), property of the richest woman in Poland, Grażyna Kulczyk.

Such prestige projects are a late hiccup of the Bilbao Effect, whereby a little-known town pins its hopes for international fame, increased tourism and measurable financial results on a flashy new architectural object. -

![]()

-

![]()

Both Łódź and Warsaw have each been heralded as the “new Berlin” from certain quarters. But this is at a time when that the economic power of the creative class, as hailed by urban studies theory svengali Richard Florida, appears to be in decline. In the face of arts budget cuts across Europe, even the strongest players, like Berlin, are struggling to play that card these days.

Nevertheless, Poland is reluctant to give up on its dream of westernisation; in fact, quite the contrary. In the last few years many of the pioneering projects conceived in this spirit have been completed and the goal of eradicating as much of the former communist architecture and infrastructure as possible is still enthusiastically pursued by a largely anti-communist and Catholic establishment. Poland’s politicians, especially at the local level, cannot and do not want to stop the neoliberal processes of privatisation and outsourcing. This has left many of their voters feeling increasingly unequal and angry with an ostensibly populist building mania that is little more than bread and circuses.

Social neglect

Real social functions seldom feature in contemporary Polish architecture. This was neatly summed up by a recent exhibition held at the temporary Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (October 2014 to January 2015) in collaboration with the major Polish architecture monthly Architektura-murator, which aimed to sum up “25 years of freedom” through models of 25 major building projects. And what was there to see? A handful of public buildings, a few district halls, one or two local community cultural houses, and some stadiums designed for the European Championship in 2012. There were almost no hospitals or schools and zero social housing. Instead the selecting jury lauded millionaires’ private institutions, several “experimental” private residencies and one “low-cost” block estate.

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

This selection was made in a national building climate where one of the greatest problems is the lack of public or affordable housing and with dodgy sales of public properties to private owners leaving many tenants threatened with eviction.

One such scandalous situation is to be found in the post-industrial city of Łódź. The very foundation of the town’s existence and its core architectural identity – factories – became shells for a massive “urban renewal”, which involved revitalising several old textile mills. This revitalisation was in fact a conversion into an enormous shopping mall complex ironically called “Manufacture”, leaving the rest of the impoverished city to rot. Some of Łódź’s most interesting developments are now happening in the remaining former factories, where the call has shifted away from vacuous new-builds towards new concepts applied to old infrastructure, which is happening elsewhere in the country as well. Sometimes the result is dispiriting, like Warsaw’s “creative cluster”, the Soho Factory, parachuted into a disused engineering works and standing in awkward contrast to the surrounding dilapidated neighbourhood. On the other hand, the Warsaw Museum of Modern Art, temporarily housed in a beautiful 1960s modernist former furniture store, has a wide audience and rich programme, and is doing very well without an expensive new building. Nevertheless, by 2020, one is scheduled to be built, next to the Palace of Culture and Science, designed by American architect Thomas Phifer.

-

![]()

-

Agata Pyzik is a writer contributing to many art, architecture and design-oriented magazines, such as Frieze, Icon and The Guardian. Her book Poor but Sexy. Culture Clashes in Europe East and West (Zero Books) was published in the UK in 2014. She often focuses on Eastern European issues.

nuitssansnuit.blogspot.comParastudio* is a functional graphics, art and design studio established by Grzegorz Podsiadlik and Maja Krysiak in Kraków in 2006. It values visual quality, identity of projects, simplicity and functionalism. Parastudio* has since attracted a lot of talented graphic designers to its team – from a country renowned for their excellent graphic design tradition. The Parastudio* project team consists of highly qualified people with broad experience – designers, artists, web and mobile developers. It has been frequently awarded and honoured in design contests, including a silver medal in the European Design Award. The illustrations for this story were drawn by Dagmara Berska and our cover illustration for this issue is by Damian Nowak.

parastudio.pl

![]()

»Polish architecture that strives to be iconic reveals our inferiority complexes and pretensions about becoming part of Europe«

Embrace the past

In contrast to the desired effect, Polish architecture that strives to be iconic tends to reveal our inferiority complexes and pretensions about becoming a part of Europe – even if we were always nominally in it anyway – hence the pushy Europeanisation of most of the new centres’ names. This strategy often displays a cynical and uneven pseudo-modernisation, associating progress and modernity only with superficial and shallow investments, neglecting any real, deeper associations with the place: its culture, history or social fabric.

One solution, albeit still utopian, could be an embracing of Poland’s peripherality, both in the geographical sense and in the feeling of isolation embedded in cultural memory, instead of pushing us as far as possible into western Europe. Visitors to Warsaw or Wrocław are not attracted because these places are like any other European city. A really bold move would be to embrace all episodes of Poland’s history and make people fall in love with Stalinist palaces and modernist pavilions alike, for the future of Polish iconic architecture might well turn out to be its past. I -

The visual spectacle of a cityscape illuminated by neon signage is most commonly associated with vistas of Western capitalism, so it may come as a surprise to learn it is also a crucial part of Warsaw’s pre 1989 heritage, and one of the few remnants of the Communist era that commands a sense of affection from many of its residents.

Intended to inform and decorate rather than advertise, the neon designs were often the results of collaboration between artists, architects and city planners.

The post-communist era has seen much neon space turn into billboard space, though in recent years things have looked a little brighter – photographer Ilona Karwińska founded the Neon Museum in 2012 to preserve displaced glass tube artworks, and in 2014 filmmaker Eric Bednarski produced a documentary about the history of the city’s fascination with illuminated gas, entitled Neon. I (fs)

neonmuzeum.org

culture.pl

![]()

Photo: © Neon Museum‚ Warsaw; video: Eric Bednarski

-

Shipyard

Photography and text by Michał Szlaga -

Photographer Michał Szlaga mourns a lost opportunity of gargantuan proportions at the former Gdańsk shipyards – the birthplace of Solidarity.

In 1999 I was allowed access to photograph the then inaccessible Gdańsk Shipyard premises. I saw production still in progress, dozens of extraordinary buildings, amazing shipbuilding facilities, kilometres of rail tracks, overhead structures and pipelines feeding the huge industrial organism. It was a fairytale world whose glorious past, which dates back more than 150 years, gradually permeated my daily life, mainly thanks to the shipyard workers, my guides to that unique place.

In 2002, with several dozen others, I moved into the Colony of Artists established by the former shipyard’s new owners and became a permanent resident. Over the years the number of artists increased; taking over abandoned buildings as the shipyard production gradually moved to Ostrów Island. This permanent presence of artists eventually caused a change in how the shipyard was perceived, namely, as a symbol of industrial decline, and we, although acting in good faith, became a propaganda tool of the investors.

In my naïvety back then, I believed that everything would work out perfectly: that the shipyard would be reborn elsewhere and that the local decision-makers, who were descended from the Solidarność (Solidarity) movement after all, and enjoying the support of trusted, excellent architects, scientists and planners, would create something special. I believed that the new owners would turn this heritage site into a valuable asset for the city. I believed that the principle underlying the entire urban design for the new district would be to preserve as many shipyard buildings, roads, facilities and local natural features as possible. I believed that the Polish State would protect these assets and that the officials, conservators and politicians responsible would do their job well.

In 2003 a barbaric local development plan was adopted after all kinds of important initiatives had been ignored, including the chance to add the entire shipyard to the UNESCO World Heritage List. -

![]()

No comprehensive research was conducted to determine its possible historical value or to make the inventory publicly available. Moreover, the development proposal included an unfortunate traffic plan, which cut through the new district in such a way that much of its historic integrity would be destroyed. All the while, those in power continued to pretend that they had the best of intentions.

The site currently has several owners who, rather than adopt a common urban development policy for the entire area, have chosen to limit their designs to their own properties. The municipal authorities who authorised the plan can now only be passive observers of what is happening to the cultural heritage of the district.

The fate of the former shipyards architecture in Gdańsk is not unique: the Fakora radiator factory in Łódź, with its pioneering eight-bay concrete factory floor from before World War: demolished; the non-ferrous metal works in Szopienice (formerly Uthemann Mill, dating from 1834): demolished; and the early twentieth century Gottwald Coal Mine in Katowice: also demolished...

In Poland we have witnessed the dismantling of many industries. It has been a painful lesson; we have inflicted punishment on ourselves but why on earth should we punish ourselves again by erasing such important historic indicators of the past, the unique resources of our cultural heritage?![]()

-

»It was a fairytale world whose glorious past gradually permeated my daily life«

-

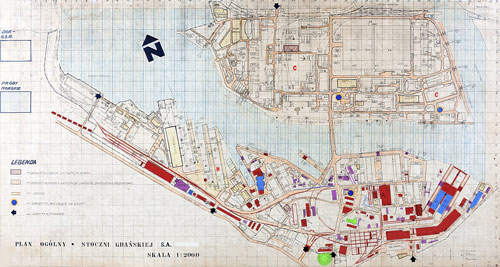

Using a plan originally used by shipyard firefighters‚ Michał Szlaga has been mapping the disappearance of the site’s architecture‚ building by building. Those already demolished are marked in red. Those marked green are protected by the city conservator. The purple buildings are currently standing but their future remains uncertain. In an update to the version which appeared in his book, blue markings indicate the buildings demolished since its publication in 2013.

Michał Szlaga graduated in 2003 from the Department of Photography at the Gdańsk Academy of Fine Arts with a final degree project called Disappearing Occupations 2003 (a series of portraits of shipyard workers), and has since become well known for his documentary photography and his work as a photojournalist.

His practice is primarily preoccupied with Polish subjects, and has included the series Polska–Rzeczywistość/Poland–Reality, which looks at contemporary Polish society. His most widely acclaimed project is Stocznia/Shipyard, a monumental documentation of the demolition of the historic shipyard in Gdańsk. In 2013, he published a book based on photographic material that he had gathered for this project since 1999.

szlaga.blogspot.de

-

More provocation than proposal, this idea by geographer Marek Pieniążek, architect and critic Gzregorz Piątek and artist Jan Dziaczkowski, is to use the rubbish and construction rubble from Warsaw to pile up a new range of Tatra-type mountains around the city. It would, say its authors, simultaneously solve urban sprawl, recycle city waste, attract tourists, raise property values and create attractive local recreational opportunities. Mountains for Warsaw is one of the Ekspektatywa series of speculations on future scenarios – each commissioned from an interdisciplinary team of artists, architects and scientists by the cultural Foundation Bęc Zmiana.

Using the hyped language of Futurist manifestos – “a grand project – sublime and beautiful as the Pyramids” – this proposal not only cleverly critiques the rudderless urban planning of Warsaw, but also provides an interesting inversion of the modern mania to build “icons” in cities as focuses for regeneration. Instead of a prominent new cultural building in the centre, here it’s a dramatic natural feature at the periphery that is proposed. p (rgw)

Image/Collage: © Janek Dziaczkowski, courtesy Fundacja Bęc Zmiana

-

![]()

![]()

Filharmonia

SzczecinArchitect: Barozzi / Veiga, Barcelona

Local Architect: Studio A4, Sczeczin

Location: Szczecin

Client: City of Szczecin

Date: 2014All photos: Jakub Certowicz

-

Based in Barcelona, Barozzi / Veiga was established in 2004 by Fabrizio Barozzi (*1976 in Rovereto, Italy) and Alberto Veiga (*1973 in Santiago de Compostela, Spain). Over the past 11 years the office has won several competitions and prizes, working on projects on all scales in Europe and abroad, creating an impressive portfolio with the Headquarters of the Ribera de Duero in Roa, the Concert Hall in Aguilas (both Spain, 2011), and the Filharmonia Sczeczin (one of five finalists for the 2015 Mies van der Rohe Award) among their internationally most well-known designs. Currently they are working on the extension of the Graubünden Museum of Fine Arts, a New Museum of Fine Arts in Lausanne, the Tanzhaus in Zürich and a School of Music in Brunico (Italy), all of which they’ve won through competition.

www.barozziveiga.com

![]()

![]()

![]()

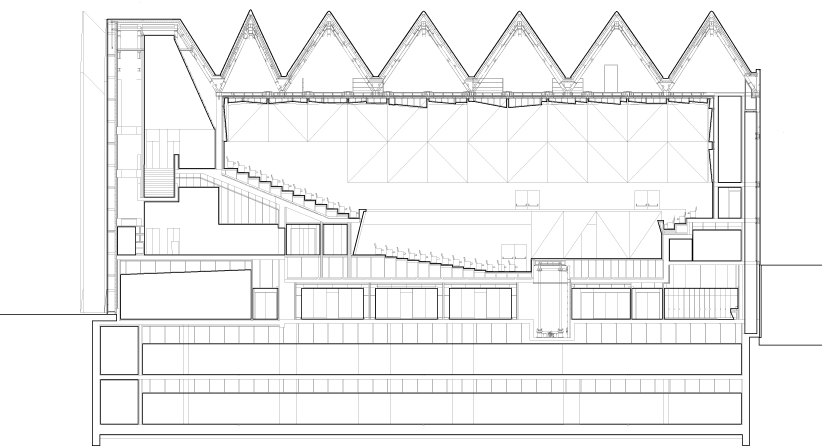

In Poland’s north-western corner where the River Oder flows into the Baltic Sea, the city of Szczecin is reinventing itself. According to the city development plan entitled “Floating Gardens 2050”, new districts are cropping up along the riverbanks and on the Oder islands. A crucial part of this plan involves new cultural institutions, the most iconic of which is the Filharmonia Szczecin – which has been realised in record time. Plans were initiated in 2005; an international architecture competition held in 2007; construction began in 2011; and the new building was opened on September 5, 2014, with a declaration by the Polish president that it served as “a symbol of our freedom”.

Designed by Barcelona-based architects Barozzi/Veiga and acoustics engineer Hirini Arau, the building is breathtaking – yet not in the bombastic-Bilbao sense of the word. While its form has popularly been compared to an iceberg, a cream pie or a building block in underwear, the architect states that the roofscape references both the cranes of the nearby shipyards and the pitched roofs of the historic houses and towers of Szczecin. Inside, beyond surprisingly generous foyers, which are lit brightly from above by large skylights, lie two concert halls, both with splendid acoustics according to the musicians who have played there so far. I (fh) -

![]()

![]()

Akademia Sztuk

PięknychArchitect: Pracownia Architektury Głowacki

Location: Wrocław

Client: Academy of Fine Arts Wrocław

Date: 2012Wrocław’s architectural past and present meet in the new Academy of Fine Arts. (Photos: Jakub Certowicz)

-

Pracownia Architektury Głowacki PAG was established in 2005 by architect Tomasz Głowacki in Wrocław. Głowacki is a lecturer at the Faculty of Architecture of Wrocław Technical University, and studied at the AA School of Architecture in London, the Technical University of Wrocław and holds a PhD from Wrocław’s University of Technology. The practice is also known for its design of private houses including House + (2005) in Wrocław, and Broken Barn House (2009) in Bielany Wrocławskie.

paglowacki.pl

![]()

![]()

In Wrocław – a city that saw 80 percent of its buildings destroyed during World War II – one can easily trace the areas where the most heavy and concentrated destruction took place. One of these, the Spoleczny Square, has been a void in the city since the war, and since the 1970s its dedicated purpose has been to serve as an oversized road junction. The new Academy of Fine Arts is the first contemporary building to face the void. It follows the line of the street, enclosing an existing housing block. Its glass skin, covered with white screen-printed dots, wraps the concrete structure, creating compelling views from inside the building, whether out towards the neighbouring expressionist post office or a small park on the east side. When its interior is lit, the building allows passers-by a glimpse into the Academy’s various workshops.

In contrast to many of the entries that were submitted by architects for the original design competition for the Academy, Tomasz Glowacki’s winning design of 2007 prizes simplicity and clarity above all – its double-height studios allow a great amount of natural light in and its wide corridors are perfect for the staging of exhibitions. At night, its sleek façade is to be the future site of a large-scale LED screen. I (Łukasz Wojciechowski) -

This clutch of high-rise residential blocks towering over the otherwise relatively low-rise heart of Wrocław acquired the nickname “Manhattan” when completed in the mid-1970s. Designed by architect Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak, their distinctive woven concrete façades hold echoes of the work of the Japanese Metabolists, with each interlocking concrete armature forming a balcony. Above, the flats incorporate roof terraces, whilst below, there are public spaces and shops. The adjacent square, Plac Grunewaldski, with its bus and tram stations, was not the result of modernist tabula rasa planning but of the tragic history of the city in the dying days of the Second World War. Wrocław, then Breslau, strategically situated on the River Odra, was besieged by Soviet troops for over 80 days and the site was razed by its Germans defenders to create a landing strip for supply planes. Today the whole area remains a key example of urban regeneration achieved not through a vanity cultural project, but by creating an integrated chunk of city for people to live in. p (rgw)

jakubcertowicz.pl

![]()

![]()

Jakub Certowicz’s “Ponad dachami Wrocławia / Over the Rooftops of Wrocław”, taken from the exhibition curated by Jednostka Architektury.

-

![]()

The rise of the Polish urban movements

By Igor Stokfiszewski

-

Igor Stokfiszewski, a journalist and activist of the independent socio-political organisation Political Critique, looks at why the recent successes of Polish urban movements seem to indicate that that people are ready for a different way of practising democracy.

Poland’s local elections that took place in November 2014 followed the usual pattern, with the ruling coalition of the Civic Platform and Polish People’s Party retaining their control over all the major cities. But there was one political surprise in the final results. The urban movement, known in Poland under the umbrella term Ruchów Miejskich (Urban Movements), which ran for the first time in elections as a nationwide coalition of city activists, won the mayor’s seat in Gorzów Wielkopolski in western Poland, and a number of city council seats in big cities like Warsaw, Poznań and Toruń.

Although a newcomer to the electoral race, the Urban Movement dictated the direction of most election campaigns. Their demands ended up in the electoral programmes of mainstream political parties, which scrambled to attract grassroots activists to their lists in an attempt to capture the young leftist vote.

So what is this new political force, and could it permanently transform Polish local and state politics?

Local initiatives

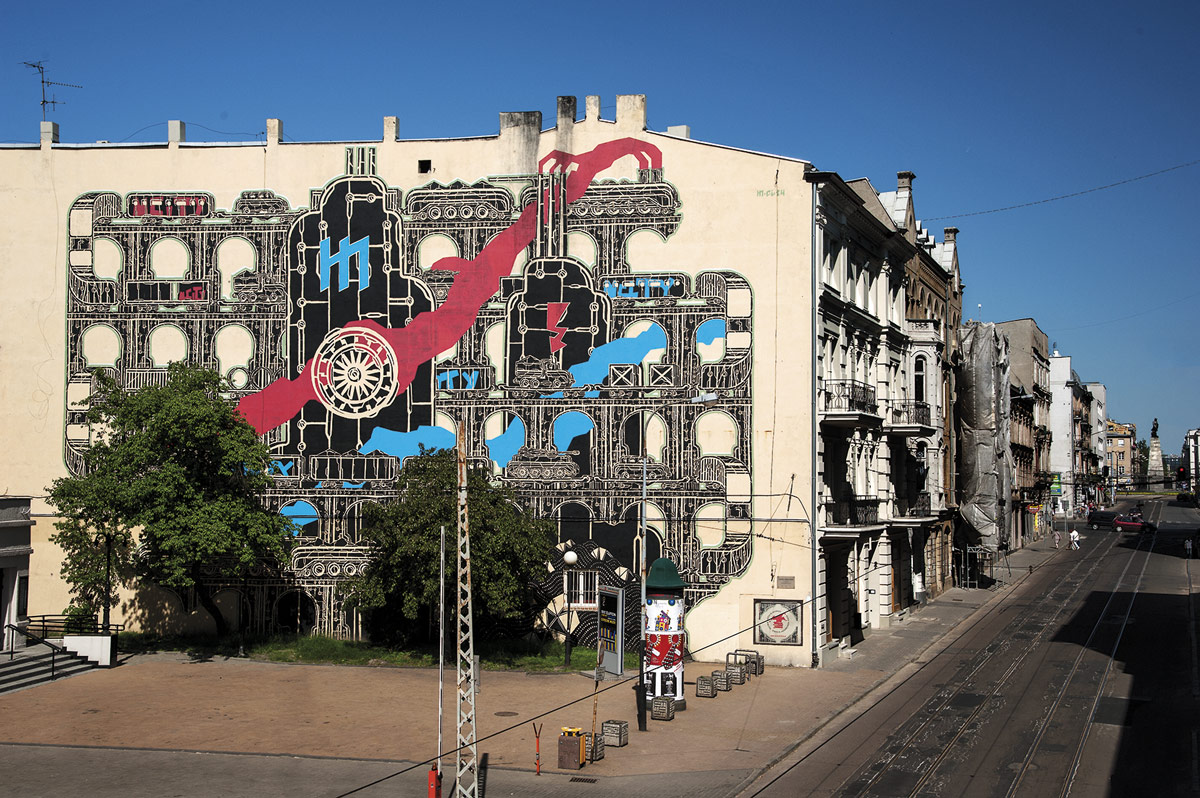

In late 2007, a group of residents of the Rataje district in Poznań, western Poland, organised to defend their right to have a say in the planning of their neighbourhood. The mayor of Poznań and the city council had proposed to transform the derelict post-industrial zone of the neighbourhood into a new residential and commercial area. Local residents, on the other hand, insisted on building a park and a recreational area.All images courtesy Galeria Urban Forms

-

![]()

In 2009 actress Teresa Latuszewska–Syrda founded an independent, non-governmental organisation, later to become known as the “Urban Forms Foundation” (FUF), to “change the city space” of Łódź by “raising its quality and aesthetics”. Art historian Michał Bieżyński also becamed involved at the end of that year.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

FUF raised funds to create giant urban artworks on tenement housing walls throughout the city by invited street artists, stating: “We want to promote ‘living’ culture and art, direct them towards people and make it possible for them to take an active part in organised events. We propagate every activity that aims at revitalising our city and county as well as the whole country through artistic creativity.”

During an annual festival, new images are added to the city’s streets. There are now some 38 murals in place from artists including Os Gemeos, Inti, Aryz, M-City, Etam Crew, Otecki, Sepe and Chazme.

-

They mobilised the community, organised protests, wrote petitions and publicised the issue in the media. The resulting negative publicity made the situation uncomfortable enough for local officials to concede to public pressure and withdraw their commercial development proposal. This was the first sign that a new social force was emerging with the potential to affect urban policies in Poland through civic engagement.

Grassroots activities began to surface in other Polish cities around that time. Activists from Sopot in northern Poland started calling for participatory budgeting following a model set by the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre in the early 1990s.

In Łódź, central Poland, an informal group of active citizens organised themselves around the issue of cleanliness of public spaces. Gradually, these groups merged into a movement calling for citizen participation in the transformation of the post-industrial area of the city, just like in Poznań. Łódź was an important industrial centre up until 1989, when its textile industry collapsed and many industrial buildings lay abandoned and derelict.

In Warsaw, urban activists organised demonstrations for the preservation of green areas in the centre of the Polish capital, against hikes in public transport fees and against privatisation of municipal buildings.

In the last few years, groups like Right to the City, Inhabitants’ Forum, and the Housing Movement have emerged in almost every Polish town, bringing together individuals of various ages, social, and cultural backgrounds. These groups were involved in a variety of campaigns to re-assert residents’ rights to their neighbourhoods and towns: from writing petitions to organising protests, from pickets and demonstrations to occupying vacant buildings, setting up squats and blocking evictions. Their political appetite grew with time. In 2010, Poznan activists formed “We, the Inhabitants of Poznan” (My-Poznaniacy), a social electoral committee to contest local elections. They received almost 10 percent of the votes, but with an electoral law favouring big political parties, they failed to get a seat on the council.

Formulating the urban commons

This electoral experience facilitated the 2011 launch of an informal coalition – the Urban Movements Congress (Kongres Ruchów Miejskich) – comprising urban activist groups from all over Poland. -

The congress was tasked with formulating a programme to provide a common foundation around which urban activists would build their campaigns in local communities. The programme was focused on three main pillars: policies to stem and reverse the growth of socio-economic inequalities and exclusion; sustainable environment-conscious urban development in the interest of all residents; and promotion of direct democracy practices such as social consultations, participatory budgeting and referendums.

On the national level, the congress managed to pressure the Ministry of Regional Development to include some of its policies in its 2012 National Urban Policy (NUP) programme. On the local level, urban activists also managed to reap a number of victories.»With the 2015 elections approaching, the Urban Movement hopes to have an even larger political impact«

In 2011 the mayor of Sopot agreed to implement participatory budgeting in the city. Residents now can decide how to spend 5 million złotys (about 1.2 million euros), or one percent of the municipal budget. Other mayors soon followed suit.

In Łódź, residents decide on how to spend 40 million złotys (about 10 million euros). The mayor of Łódź also invited local activists to advise the city council’s Revitalisation Bureau on specific policies for the socio-economic development of the city. The reason that Łódź became more accepting of the urban movement’s demands was because its previous mayor, Jerzy Kropiwnicki, was removed in a popular referendum in January 2010. The mayors of Częstochowa, Olsztyn, Elbląg, Bytom and Ostróda were also removed in the same manner for introducing policies regarding privatisation and commercial development that went against the will of their electorates.

-

The FUF encourages local interaction and discussion about the murals – raising awareness and interest and encouraging civic pride and engagement within the community. The initiative has made the post-industrial city of Łódź, dubbed the “Manchester of Poland”, one of the most important centres of street art in the world

-

Igor Stokfiszewski is a journalist and activist of Political Critique, an independent sociopolitical organisation operating within Poland and Ukraine.

politicalcritique.org

A slightly longer version of this article first appeared on Aljazeera.com on December 9, 2014 under the title: The Rise of Poland’s Urban Movement. Republished courtesy of Al Jazeera.

![]()

The project has now attracted local business and local government investment. Visitors come from all over the world to tour the city streets – because of the street art. But they also stay to learn more about one of Poland’s most striking former nineteenth century industrial centres.

![]()

Grassroots victories

The same fate threatened the mayor of Warsaw, Hanna Gronkiewicz-Waltz, but a low turnout at the referendum saved her and she later quickly implemented some of the urban movement’s demands. But the most spectacular achievement of the Polish urban movement in recent months was putting Kraków’s candidacy to host the 2022 Winter Olympic Games to a referendum. To the displeasure of the local authorities, some 36 percent of Kraków’s citizens voted and 70 percent of those said “no” to the games.The Kraków victory incited the formation of a nationwide coalition of 12 socio-political entities affiliated with the Urban Movements Congress to contest the 2014 local elections. The results of the election demonstrated that the movement can translate its grassroots support into electoral victories. With the 2015 parliamentary and presidential elections approaching, the coalition is hopeful that it will have an even larger political impact.

The urban movement has a long way to go in order to occupy a permanent place on Poland’s political map. But its public presence, successful campaigns and increasing social support show that there is a definite shift in Polish people’s socio-political attitudes. There is clearly growing support for sustainable and environmentally conscious development, which aims to level out inequalities and exclusion and usher in effective practices of direct democracy. I -

![]()

![]()

Photos courtesy Krzysztof Ingarden

Muzeum Sztuki i

Techniki Japońskiej

Manggha w KrakowieArchitect: Arata Isozaki / Arata Isozaki & Associates

Collaboration : Krzysztof Ingarden / Jet Atelier

Location: Krakow

Client: Kyoto-Krakow Foundation

Andrzej Wajda and Krystyna Zachwatowicz

Date: 1994 -

Arata Isozaki is an architect from Ōita in Japan. He graduated from the University of Tokyo in 1954 and worked for Kenzo Tange before establishing his own firm in 1963. His early projects, such as Oita Medical Hall, 1959-1960, exhibited a style Reyner Banham called: “a mix of New Brutalism and Metabolist Architecture”. He then developed a more eclectic style with buildings such as: Fujimi Country Club (1973–74) and Kitakyushu Central Library (1973–74), which later became more modernist in feel with buildings such as the Art Tower of Mito (1986–90) and Domus-Casa del Hombre (1991-1995).

www.isozaki.co.jp

manggha.pl

![]()

Krakow’s Japanese Centre of Art and Technology, or “Manggha” for short, houses the collection of Felix Jasieński (pen name Manggha), a Polish art critic and collector who travelled extensively through Europe and the Far East in the nineteenth century. The Centre was initiated by another of Poland’s most famous citizens, the Oscar-winning film director Andrzej Wajda who, as a recipient of the Japanese Kyoto Prize was so keen to forge links to Japanese culture in his native country that he donated his prize money for this towards the Centre’s construction.

Fittingly therefore the building was designed by Japanese architect Arata Isozaki, who famously meshes eastern and western influences in his projects. The Manggha Centre remains the architect’s only building in Poland and its conception and completion in the early 1990s was a landmark, if initially controversial, project for the country. The building’s galleries blend the wood and brick, prominent in traditional Japanese interiors, with Polish sandstone, whilst the undulating roof is intended to echo the form of a wave, a reference to both a key subject in Japanese woodblock prints, as well as the site’s location perched directly on the Vistula river. I (fs) -

![]()

![]()

Stadion Miejski

Architect: J.S.K Architekci

Location: Wrocław

Client: Wrocław 2012

Date: 2011 -

J.S.K Architekci, founded by its directors Zbigniew Pszczulnego and Mariusz Rutz, has an international team working primarily on projects in Germany and Poland. The practice has designed office buildings, retail and residential projects but specialises is the design of airports and rail terminals, sports stadiums and arenas. Projects have included: the Daimler HQ in Warsaw and the Legia Warsaw football stadium as well as two stadiums for the UEFA EURO 2012 tournament: the Wrocław Municipal Stadium and Warsaw National Stadium. Current projects include the expansion of the Wrocław Starachowice International Airport and the Lech Walesa Airport in Gdansk.

![]()

Driving the new highway ring on the west side of Wrocław allows one to catch a glimpse of an intriguing building. Come after twilight and you see what appears to be a giant lantern of changing colours, whereas during daylight hours you are greeted by a vast, translucent white oval membrane. The structure in question is the Wrocław Municipal Stadium, built as one of the venues for the UEFA Euro 2012 football competition in Poland and Ukraine.

The competition to design the stadium, with a capacity of 45,000, was won in 2007 by Warsaw architects J.S.K Architekci. Its neighbour on one side is a distinctive Zaha-Hadid-style reinforced concrete tram stop by local architecture office Mackow Pracownia Projektowa. But on the other side a void has been left, after preparations for building a shopping centre were abandoned by a private developer.

The stadium’s most spectacular feature, its façade of translucent fibreglass mesh covered with Teflon, is also a reminder of just how much the stadium cost: a not immodest 170 million euros. And although this expensive building was intended to hold live music, festivals and various sporting events after the games, it has proved difficult to fill it to capacity since. I (Łukasz Wojciechowski)Photos: Jakub Certowicz

-

![]()

Warsaw’s Palace of Culture and Science: white elephant or national treasure?

Text by Agnieszka Rasmus-Zgorzelska

Photography by Jacek Fota -

![]()

Daniel Libeskind’s Złota 44‚ seen here on the left during its construction‚ is one of several recent‚ towering additions to Warsaw's skyline. (Photo this page only: Lara Eurdolian)

With the new wave of representative cultural buildings popping up all over Poland, Warsaw-based Agnieszka Rasmus-Zgorzelska takes a close look at the city’s most prominent cultural icon: the huge Palace of Culture and Science, a “contaminated gift” in the 1950s from Stalinist Russia to the young communist People’s Republic of Poland.

-

Even today the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw remains both a symbol of sinister Stalinist domination and a beloved icon for those of us who live in the city. Whole urban districts dating from the nineteenth century, largely damaged during the war, were devoured to make place for its gargantuan body and imposing parade ground. It is disconnected from the city centre and yet sits at its very heart. Before its vast expanse, we are either paralysed and powerless – or seduced. 2015 marks the 60th anniversary of the Palace and a series of publications and events are coming up. Will they break the spell this building still holds over our city and citizens?

Conceived as “a gift from the Russian people to the Polish nation”, the Palace was almost fully financed by the USSR, designed by Soviet architect Lew Rudniew, and built between 1952-55 by an army of 3,500 Russian builders. Modelled on the Stalinist “Seven Sisters” skyscrapers defining the 1953 Moscow skyline (themselves inspired by American architecture), it was nicknamed the “Eighth Sister”. With its functional programme it was clear that culture would take precedence over badly needed housing – and the form of the building took centre stage: The intention was to be “socialist in content, national in form”, yet, with a rather vague notion of the “national”, details were borrowed from historical monuments from various Polish towns. Perverse as it was for a poor post-war country, the interiors were fitted out by the best Polish craftsmen who made elaborate glass and ceramic lamps, wood panelling and custom designed furniture.After 1989 the Palace continued, as before, to be home to popular theatres, museums, a cinema, auditorium, swimming pool and viewing platform – supplemented by commercial offices and space for rent. With the newly regained economic freedom the surrounding Parade Square proved a convenient site for provisional stalls, later replaced with temporary covered markets. However, their ugliness was so incongruous with the ambitions of a city defining itself anew that they were finally pulled down, to make way for a “more civilised” use, which turned out to be a series of guerrilla coach stops for buses shuttling to satellite towns, and a vast parking lot in a dishearteningly dilapidated space. This is the current state of the Square in 2015.

-

![]()

Władysław - shoemaker at the “Dramatyczny” theatre

![]()

Celina - a cat keeper inside the “Cat Paradise”

![]()

The stage at the Sala Kongresowa (Congress Hall)

-

»a gift from the Russian people to the Polish nation«

Backstage during a production of the play “Młody Stalin” at Dramatyczny theatre.

-

At least three versions of a plan were made for the Palace and its surroundings in post-communist Warsaw. The first, from 1992, comprised several alternative propositions, the main one had a “Warsaw Crown” of towers arranged in a circle. Focused on a high-rise vision, the plan aimed at diminishing the Palace’s domination, yet accepted it by adjusting the whole symmetrical composition around its centrality. It evoked fierce public discussion but in the end no action was taken. In an atmosphere of general inertia the architects dropped the project. Then there was a political change in the city government and new energy appeared. Another plan was made, this time encompassing low-rise buildings, an agora and included a new Museum of Modern Art: an open, contemporary building as a new symbol of Warsaw.

As it turned out, during an unsuccessful attempt at realising this museum with a design by Christian Kerez, the city had not solved the fundamental problem of land ownership. Following the Bierut Decree from 1945, all Warsaw properties were nationalised. Yet with the return of capitalism, the Parade Square returned to being a chessboard of smaller plots, many of which remain stuck in the process of reprivatisation to this day. Another plan was approved in 2010, basically a compilation of numerous former versions, allowing again for high-rise building, higher density and a more versatile functional programme. However, apart from the Museum of Modern Art, which is now to be designed by American architect Thomas Phifer in the north-eastern corner of the square, the current city government does not seem to be undertaking any further action. Is there a psychological barrier that has made it so difficult to tackle the space in the Palace’s shadow? Ever since its completion, the building has evoked such strong emotions that its demolition has been proposed several times since 1989. Yet these tended to be rather isolated calls, and its entire destruction was officially never seriously considered, indeed in 2007, the Palace was finally listed. -

While the palace is undergoing slow but consistent refurbishment inside, it offers, as ever, a vivid and varied cultural and social programme, with its two theatres, the best puppet theatre in town, one museum for technology and one for evolution, as well as a cinema to name just the main elements. The Palace of Youth, which shares the north-western wing with a swimming pool, complete with a diving platform, has become home to numerous highly popular and accessible extracurricular courses.

![]()

In the meantime, to the west of the square and next to the central train station, Warszawa Centralna, a cluster of skyscrapers has been added to Warsaw’s financial district. Their designers include big international firms like SOM, Helmut Jahn and Daniel Libeskind (building for the first time in the country of his birth). Libeskind’s residential tower was allegedly consciously designed to outshine the palace. In the event it has proved even uglier than the renderings promised, and its interior remains unfinished since the developer went bankrupt.

Marianna – a rhythmic gymnastics student inside a gymnasium at the Pałac Młodzieży (Palace of Youth).

-

Agnieszka Rasmus-Zgorzelska is an independent, Warsaw-based architectural author, editor and curator. She is also co-founder of the Centrum Architektury in Warsaw.

centrumarchitektury.orgPhotographer Jacek Fota graduated with a masters degree from the University of Utah, USA before returning to his native Poland and getting involved with documentray photography. He received a scholarship from the city of Warsaw to develop a new book, PKiN, which will be published in June 2015.

jacekfota.com

Quite obviously, none of the new skyscrapers have the quality to seriously threaten the craftsmanship that was put in the façades and public interiors of the Palace. Also, since no serious masterplan for Warsaw’s city centre exists, it becomes apparent that all these big buildings don’t create a new, interesting collective but remain egocentric entities, each one only interested in itself. The Palace, a product of Stalinist ideology, has now simply been joined in the city centre by some products of capitalism. Will they ever start talking to each other, one wonders, turning the dead void of Warsaw’s most important square into lively, democratic chaos? I

Gymnasium at the Pałac Młodzieży (Palace of Youth).

-

Because of its oft monumental scale, Soviet-era architecture has lent itself to the purpose of mega-advertising with surprising ease. Take, for example, the former Hotel Forum in Kraków, located on the south bank of the Vistula. Designed by Janusz Ingarden, construction began in 1978 and it took more than a decade to complete. When it opened, it was regarded as one of the city’s most modern buildings. Sadly, this bulding’s glory days seem firmly behind it – the hotel has long vacated the building, which now supports the rather less glamorous function of being Poland’s longest billboard. In 2013, Miasto Moje a w Nim (“My City and In It”), a group who campaign to reduce the high visibility of billboard advertising across the country, awarded the hotel-turned-billboard the dubious honour of “most ugly example of advertising that ignores the local context”. p (fs)

Radoslaw Ziomber / CC-SA 3.0

Radoslaw Ziomber / CC-SA 3.0

Photo: Simon Kirwan

-

![]()

Focus on Polish Design

![]()

After completing his studies at the Pratt Institute in New York and the RCA in London, product designer Tomek Rygalik returned to his hometown of Łódź in 2006 and to the nascent Polish contemporary design scene. He is one of Poland’s most internationally renowned contemporary designers and as such has been instrumental in raising the profile of his country’s design and furniture industry, as well as investing time and effort in helping the next generation of young Polish designers develop their own voice and qualities.

In 2012 he joined forces with his wife, the food designer Gosia Rygalik, and together they run their Studio Rygalik from Warsaw. For our Poland issue, uncube asked the Rygaliks to focus on four key organisations, institutions or companies who, in their view, are pioneers in the contemporary Polish design landscape.Photo courtesy Studio Rygalik

-

The Adam Mickiewicz Institute

—

The Adam Mickiewicz Institute, also known as Culture.pl, actively promotes Polish culture abroad in many ways: by organising and co-funding exhibitions and cultural events worldwide, as well as by supporting things like publications and film productions. Design, along with other artistic and creative disciplines such as film, music, theatre and photography, is one of their main areas of focus. One of their biggest design related initiatives in 2014 was the launch of our own curatorial project: NASZ Collection at WantedDesign in New York.

![]()

Studio Regalik objects for the NASZ collection. (Photo: Ernest Winczyk, courtesy Studio Rygalik)

-

![]()

VZOR

—

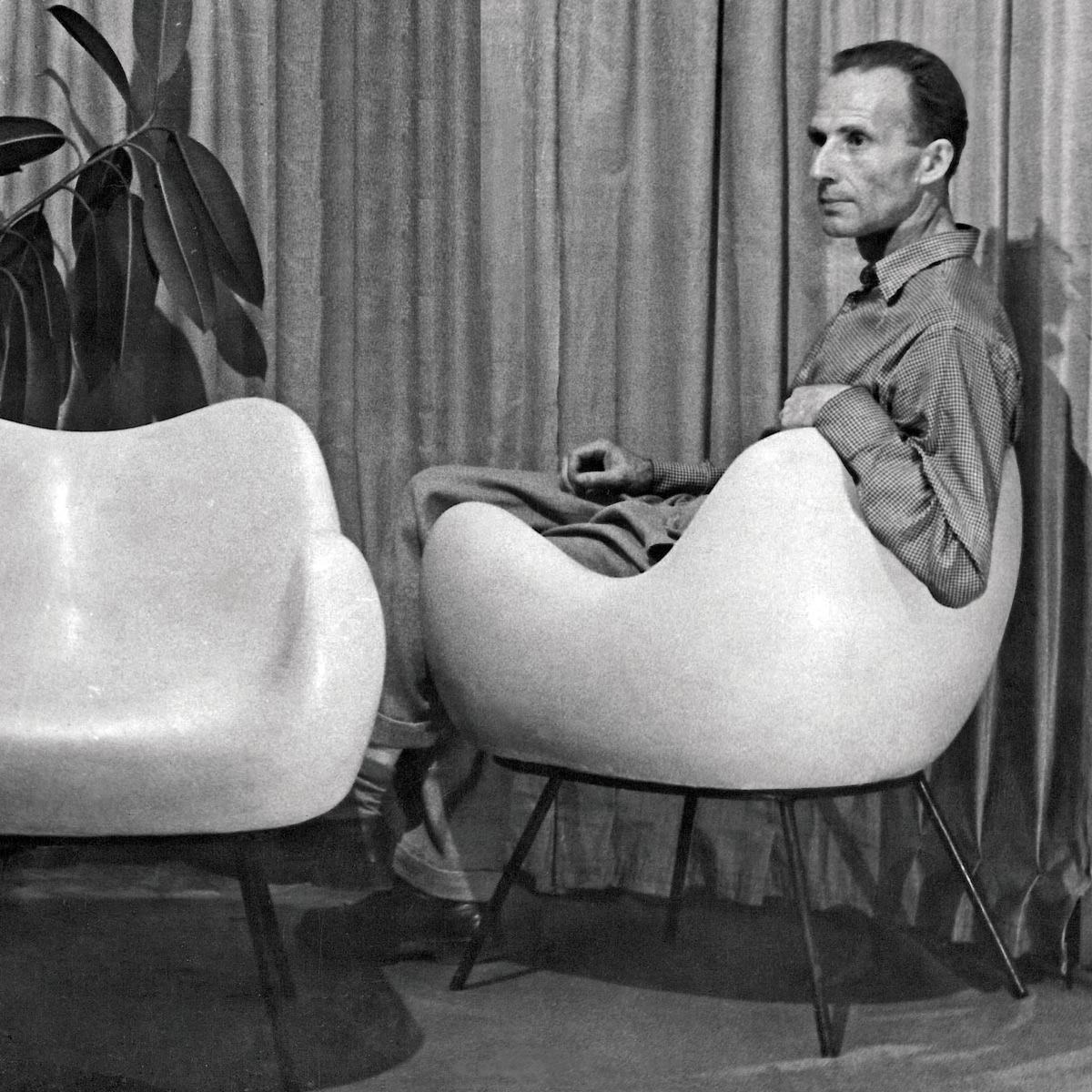

Polish design history has many icons that in the past could never be produced, because of the political situation. They just didn’t fit into the communist ethos. Vzor is a furniture brand that was established in 2012 in order to reissue iconic Polish furniture designs. They began by introducing the cult RM58 armchair, designed in 1958 by Roman Modzelewski. The brand’s aim is to bring fantastic designs from the fifties and sixties to the market – adapting them to serial production and reinterpreting them with modern technologies.

![]()

Roman Modzelewski and his original RM58 armchair and the Vzor re-issue. (Photos courtesy VZOR)

-

![]()

Łódź Design Festival

—

For some reason, Poland’s main design event doesn’t take place in either the capital city, or alongside any major trade fairs. In 2007 an annual design festival was founded in the culturally vibrant city of Łódź. Since then the event has grow continuously and gained importance both in Poland, and internationally. The programme is always based on a specific theme with curated exhibitions and an open-call exhibition complemented by a diverse range of events, including lectures and parties.

Tabanda’s “Strefa Testów/Test Zone” shown in Łódź, 2014. (Photo courtesy Łódź Design Festival)

-

![]()

furniture manufacturers turned furniture brands

—

Not many people know that Poland is one of the biggest manufacturers of furniture in the world. This leading position, however, is one of sheer volume of export (calculated in kilograms), not turnover. Polish companies produce for brands all over the world, including Ikea and Vitra. A few pioneering manufacturers are realising that they need to shift from OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) to OBMs (original brand manufacturers) to keep in step with Poland's economic growth. Three of these brands are: the upholstered furniture manufacturer Comforty, the office furniture makers Profim and the contract seating manufacturer Paged. Studio Rygalik has designed furniture for all of them.

Paged “K2” family designed by Tomek Rygalik. (Photo courtesy Paged)

-

![]()

-

![]()

Issue No. 32:

March 26th 2015The UK Pavilion under construction at the Shanghai World Expo 2010. (Photo: Daniele Mattioli‚ courtesy Heatherwick Studio)

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Intelligence starts with improvisation.«

Yona Friedman

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents

ost-War, post-industrial and post-communist, Polska has certainly had its fair share of struggles and identity issues. But the past decade has seen a land best known for its industrial powerhouses turning instead to the production of cultural capital as a huge wave of investment in cultural infrastructure hits almost every Polish city.

ost-War, post-industrial and post-communist, Polska has certainly had its fair share of struggles and identity issues. But the past decade has seen a land best known for its industrial powerhouses turning instead to the production of cultural capital as a huge wave of investment in cultural infrastructure hits almost every Polish city.