Sophie Krier is on a permanent field trip. A designer and educator based for many years in Rotterdam, she is currently at a year-long Cité des Arts residency in Paris in order to develop her ongoing publication called Field Essays. Published by Onomatopee, Field Essays is a unique experiment in bringing practitioners across disciplines into a conversation circulating around design. But the aim of the project is not “interdisciplinarity” as such – it utilises the publishing platform as an autodidactic tool for broad exploration, letting the “what” of learning dictate the “how”, as Krier puts it. In the spirit of a journey without a fixed destination, uncube put on a backpack and started a conversation with her about education, publishing and design without a roadmap.

On the surface your education in textile design doesn’t directly relate to the work you do today. How did it inform your practice?

That question is at the core of what I’m doing at the Cité des Arts residency in Paris this year. I’m here to reflect on the past 15 years and see if there are connecting threads. In my case, those connections may not feel so logical at the time, but afterwards they usually do. For instance, during my design education, I felt I was missing out on learning about the social dimension of design practice. But what I was learning, weaving, a way of working very related to textiles, is about connecting things, making a pattern from nothing, starting with the structure of the weft and weaving through it to build a narrative. During my education I knew that I was interested in narratives, that I liked language, and had good drawing skills – but I had to invent my own role, which is something I’ve always enjoyed doing even though it’s scary at the time.

So in a way your education was successful in that it forced you to take your own position.

I’m sceptical about making judgments on my educational experience, because my perspective is different now from then. While maybe my experience was a bit confined to a practical approach, the whole idea that designers can also be researchers hadn’t really emerged yet. I studied between 1995 and 1999 – and graduated without computers!

After graduating I opened my practice in Amsterdam in 2000, firstly joint with a colleague and from 2001 as my own studio. At the beginning the work was based on my graduation project – a set of fictive props for a film – and I was working on scenographies for exhibitions. Then that shifted to curating events and symposia, and somehow the public space and social element came into it too.

Once I finished my education, I was able to reconnect the skills I’d learned with my actual interests. I don’t know if that connection is really possible within the education context. Maybe I’m super classic in thinking this, but I think Bachelors is for the basics, to really lay down the foundation of a profession, a craftmanship, an attitude or way of working, and then the Masters and PhD allow you to build on that.

So you’re not against the formalised system of moving through various degrees?

No. I think by the time you get to Masters you should really have your own research topic that you try to develop within those two years. Not every Masters programme makes this possible. The Temporary Masters at Sandberg, for instance, is great because it does – students pick a topic and then work on it for two years in a protected research studio, without the financial risk and all the other factors associated with real practice. The beautiful thing about education is that you’re allowed to make mistakes. You have peer review, and time is free; a teacher isn’t going to charge you for speaking with you half an hour longer! But personally, I think I used my practice as a Masters. I had to be my own critic and peer review.

Is that where Field Essays comes in? As a publication it definitely deals with questions of being “in the field” as in learning from the profession, using your career as an ad-hoc Masters programme, and turning the process of learning into a product.

The title Field Essays says it all. It contains the two reasons I’m still in design: the field is the moving outwards, doing fieldwork, being on-site, seeing how things work in reality; the essay refers to Montaigne’s idea of reflection – not necessarily a theoretical reflection, but a personal kind. Essay also has the French word essai in it, which means “attempt”. So I really like the meaning of those two words, the moving out and then the moving in to reflect on what you’re doing. This movement is very important to nurture, and every person has a different rhythm. Some people are more into the reflecting part, and some people are real makers and need other people to reflect on them. I happen to be a person who loves both.

How did you arrive at the idea for Field Essays?

It’s a bit enigmatic, but I can trace it back to 2006 when I joined a research group called the Professorship of Art and Public Space at the Rietveld Academy, which was for teachers, artists, designers – anyone wanting to conduct “fundamental research”, as they called it. They meant that the research should not be project- or commission-related, but rather have its own timeline and weave itself into projects over time. For me joining the group was like “whoa” – for the first time I was asked what I was really interested in and how I wanted to contribute to the world, which is very different from completing a brief or reacting to a specific situation.

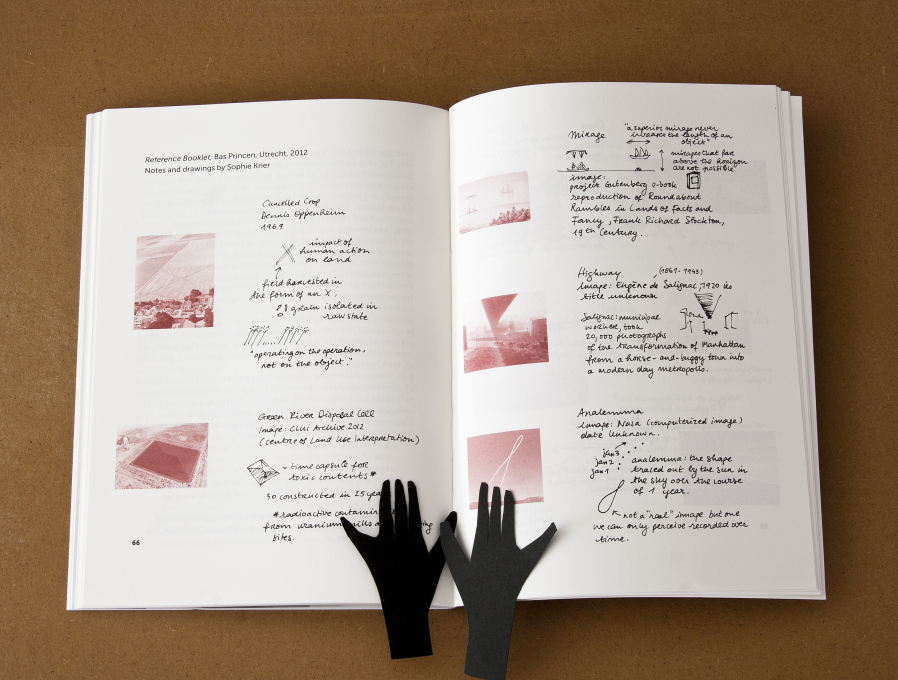

In the beginning I focused on collaborations between two or three designers, because when you work with another person your mental process becomes verbal or sketched out – explicit. I realised I was interested in the way that design choices are made, and the consequences of those choices, however miniscule they might be, for ethics. I had planned to make a documentary and to write essays on the topic, but then I realised I needed a format to frame this research. I needed something that would provide evaluation moments, like in education. That turned into the idea of publishing a series of books.

And now you are working on the third issue in the series. How has the process informed each iteration?

So far the process remains incredibly intuitive. I choose the protagonists on instinct. Their work grips me, either because I don’t understand it or find it super strange, and see something in their work that I haven’t seen elsewhere.

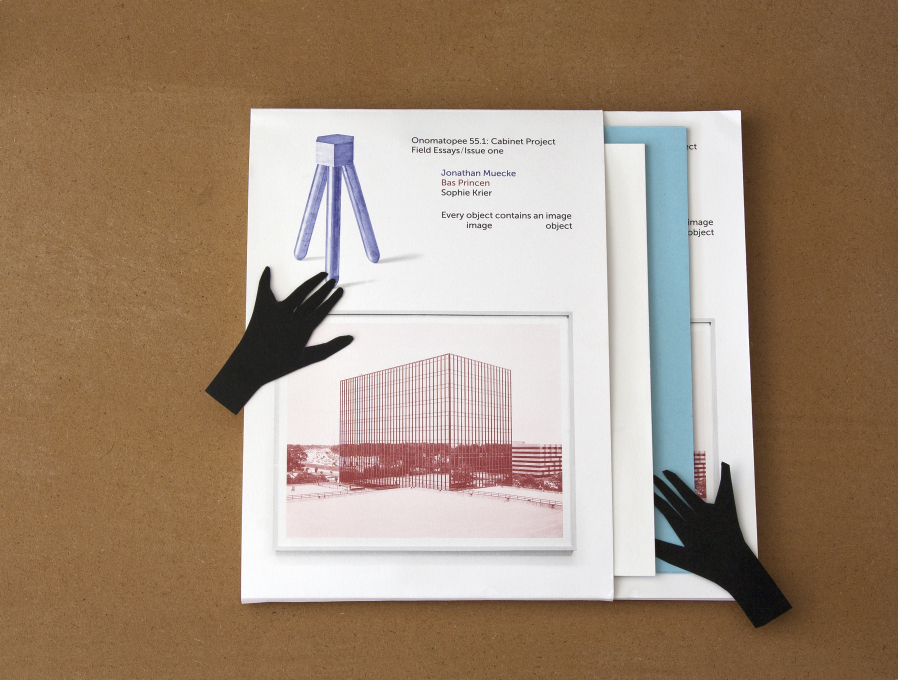

The first issue, where I connected the design duo Lucyandbart with the philosopher Marek Popropski, was a kind of classic 1.0 version: you have a designer and you look for the theoretical framework that can inform what’s happening in the design process. But the second issue was much more experimental. I met designer Jonathan Muecke in his studio, where he had an 8-metre-long stick. I asked him what it was and he said, “I don’t know how long it is, but I made it to measure the world with.” That was the the sentence that hooked me.

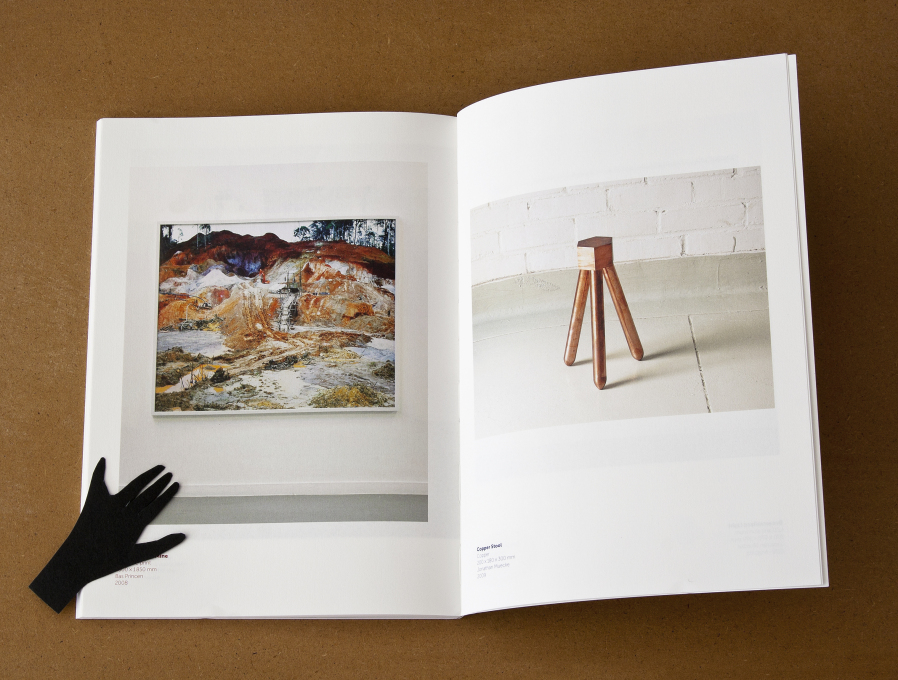

The connection between him and the photographer Bas Princen was made mainly visually. Jonathan had made this copper stool object, and I remembered an image by Bas of a copper mine. I had the feeling that the two pieces could have been one work. Eventually I managed to bring them together in real life, which didn’t happen in the first issue, and I had been right: there is a kind of chemistry between the two.

The current issue with the designer Brynjar Sigudarson is again very different. I’m reconsidering my own voice in the publication; I will not actually write about him this time. My voice is only present in the editing of the material, and the other choices – we’re producing a vinyl record to go with this one!

It sounds like the publication format originally allowed you to frame and condense your ideas, but is now providing a platform to launch from.

Right. And if I compare it to building a website or something, I really like that the two finished issues of Field Essays are just that: finished. Even if I want to change some words now, I can’t, because they’re printed and circulating in the world for people to react to or not. It’s true that we are adding more, such as the audio dimension, but it’s good to have some things you can’t undo. What I like is that there is no external time pressure; on average it takes two years for an issue.

Until recently it was like a reflection tool on the side of my practice, but the decision to come to Paris for a year was to see if I could put Field Essays at the centre. It might even lead to creating a Masters program around Field Essays.

You’ve worked extensively as an educator – how did it change your ideas about being a student?

I led the DesignLAB department at Rietveld between 2005 and 2009, and had the time of my life – I think the students did as well! The great thing there is that I had a lot of autonomy and could construct my dream education. We started with what I called “Process Sessions”, where teachers would present their interests and then the students would enter into dialogue with them to decide what to work on over the year. That’s different from the usual situation in which the topics are laid out for everyone in advance and at some point might intersect within the framework of the set assignment.

Projects like the Travelling Academy that I worked on there were born from thinking about internationalisation in the school system. Rietveld is known to be very international, but that refers to 60% of international students coming in to the school, not the Rietveld itself travelling. So we imagined the model of the Travelling Academy, based on the notion that your education is like a backpack, which can be very light.

There’s a beautiful quote by Louis Kahn, where he says something like: “education started with a man standing under a tree who did not know he was a teacher, discussing his realisation with a few sitting around him who did not know they were students”. Meaning that in the beginning education was not about all these roles, about the school building or the structure around it: it was about transmission of insights.

So did this teaching experience highlight the importance of the interdisciplinary approach that you’ve worked with in Field Essays?

Yes, it highlighted the importance of it, but I also understood that before going into the “field” you need to prepare your ground first. The danger of interdisciplinarity is when you don’t know where you’re coming from. It’s great if it makes sense with the topic you’re working on, but even then it should never be the first aim in education. It’s like putting the method before the content. I still think that what is being learned comes before how you learn it. The “how” helps the “what,” but the “how” should never go first. The question is what kind of knowledge you produce. Now you should ask me what kind of knowledge I want to produce with Field Essays!

Let me take a guess: if the aim isn’t interdisciplinarity, it’s about following trails of content and seeing where they lead.

Yes. And I’m even coming back to the idea of the textile. Maybe it just took me this long to figure out what I want to do with my education – and what I’m able to do with what I was taught. There’s that incubation time you have to think about when you assess education.

I need to study the practice of others to understand my own practice. That’s what Field Essays has given me: seeing what others do and understanding what choices they make allows me to ask what I would have done.

- Elvia Wilk

Sophie Krier is a designer based in Rotterdam and Paris who explores the peripheries of the design field through field work in the public domain. She has recently been nominated for the Dutch Design Awards for her project “Hunnie” with Henriëtte Waal. www.sophiekrier.com

Further reading:

School’s Out: uncube issue no. 26

An Ecology of Technologies: Interview with Hitoshi Abe

Building both as Verb and Noun: Interview with Yung Ho Chang