It’s exactly half a century since ground was broken on Berlin's most recognisable symbol, the radically modern structure–as-gesture of the Fernsehturm, or TV Tower, on Alexanderplatz. To celebrate this, we feature some remarkable pictures of its construction taken by Karl-Heinz Kraemer, while Fiona Shipwright considers how well the futuristic spirit of this “Tower of Signals” – despite being a relic of socialist might and a Soviet Bloc long since passed into history – compares today to some of the historical navel-gazing going on in the present-day city.

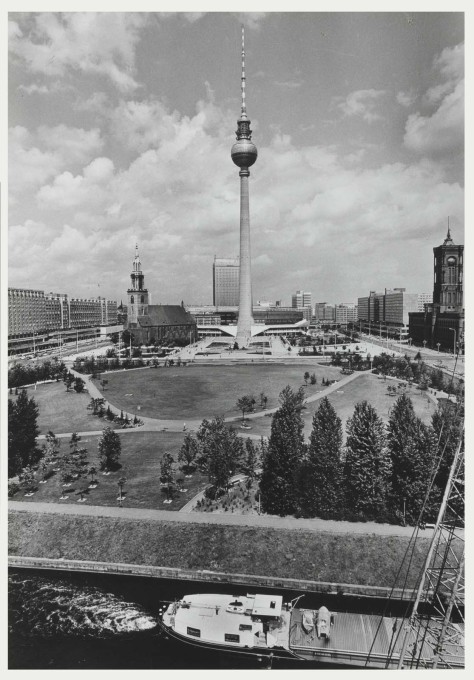

On August 4, 1965, construction began on, what has become the definitive architectural icon of Berlin, perhaps even of Germany as a whole, signifying the restored capital of the reunited country. Its ubiquitous presence, not just on the skyline, but across the spectrum of the city’s visual paraphenalia – from tourist key rings to health insurance advertisements, from graffiti to manhole covers – makes clear its status: tower as signifier, a symbol of the city.

This was never the intention of its designers and builders, or at least not in relation to the Berlin that we know now. At the time of construction there were two Germanys, and rather than sited at the centre of a unified city, the tower sat not far from – and offered a view over – the physical barrier of the Berlin Wall, that divided East from West for 28 years.

At 365 metres high, the Berliner Fernsehturm, or TV Tower, was, following the radically modern planning of the time, the tallest structure in Germany on completion – and remains so. Its hyperbolic stature was intended to represent the efforts and achievements of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the communist political system which had brought it into being (even if things didn’t always feel quite so progressive on the ground). In seizing the empty sky above the still relatively low-rise city, the East German regime was able to control the cityscape with a physical embodiment of their endeavours that quite literally towered over – as well as put one big finger up – to the West.

It is no accident that when East Berlin’s head architect Herman Henselmann entered the original design for a tower in the 1958 competition “Ideenwettbewerb zur sozialistischen Umgestaltung des Zentrums der Hauptstadt der DDR, Berlin” (Competition for the Socialist Re-design of the Centre of the Capital of the GDR, Berlin) he called his proposal “Turm der Signale” (Tower of Signals). The communicative function of this tower was to extend far beyond broadcasting radio or television waves, the TV Tower’s very structure, joining a family of other soaring, technoid structures rising above cities throughout the Soviet Bloc, embodied the two socio-political narratives which defined that era: the Cold War and the Space Race.

In August 1964, when ground was broken for the tower, the USSR’s star was (quite literally) in the ascendant. Sputnik had become the first man-made satellite to send signals back from space and the Soviets had put the first dog, man and woman into orbit (even if only two out of three came back alive), in an on-going battle of interstellar egos with NASA, who had managed some planetary flybys by then. And fuelled with a sense of space age bravado, so the story goes, the GDR pushed ahead with a futurist, Sputnik-emulating design for the tower in Alexanderplatz, to head up the grand Socialist boulevard of Stalinallee (today Karl-Marx-Allee) at the centre of their capital. The project was scheduled for completion by October 3, 1969 – the 20th anniversary of the GDR’s founding. But in the event, this anniversary was a bit upstaged by NASA’s landing of (American) human beings on the moon on 20 July earlier that same year.

However, pleasingly neat as this story arc is, both the siting and space age form of the structure were more down to chance and pragmatism rather than destiny. Originally a signature governmental high-rise building was planned for East Berlin’s city centre, but on a different site at the Marx-Engels Forum, while the city’s broadcast tower was intended to be built far out on a range of hills in its south-eastern outskirts, the Müggelberge. But the Marx-Engels Forum site proved too marshy for a high-rise, while simultaneously it was realised that the Müggelberge site for a broadcast tower would interfere with the flight path to nearby Schönefeld Airport, so both plans were abandoned. But then, the GDR State Council revived Henselmann’s 1958 proposal, seeing in it an opportunity to salvage the best ideas from both projects and create a single stronger one: a symbolic “Tower of Signals” at the heart of the GDR capital. While it was Henslemann who had initially conceived the idea, in the event, the actual structure’s design was the work of two architects: its concrete shaft designed by Günter Franke, its crowning sphere by Fritz Dieter.

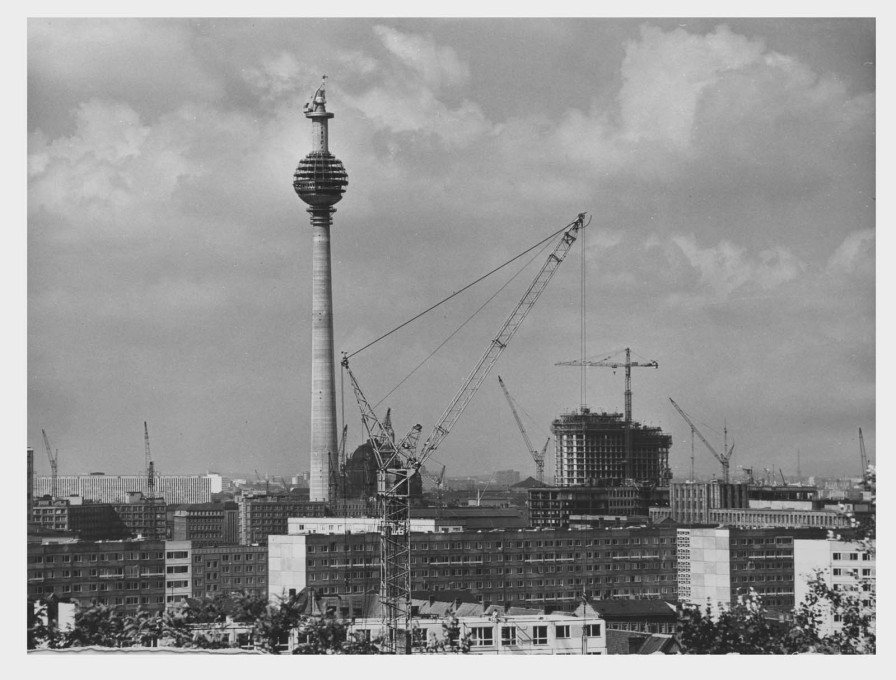

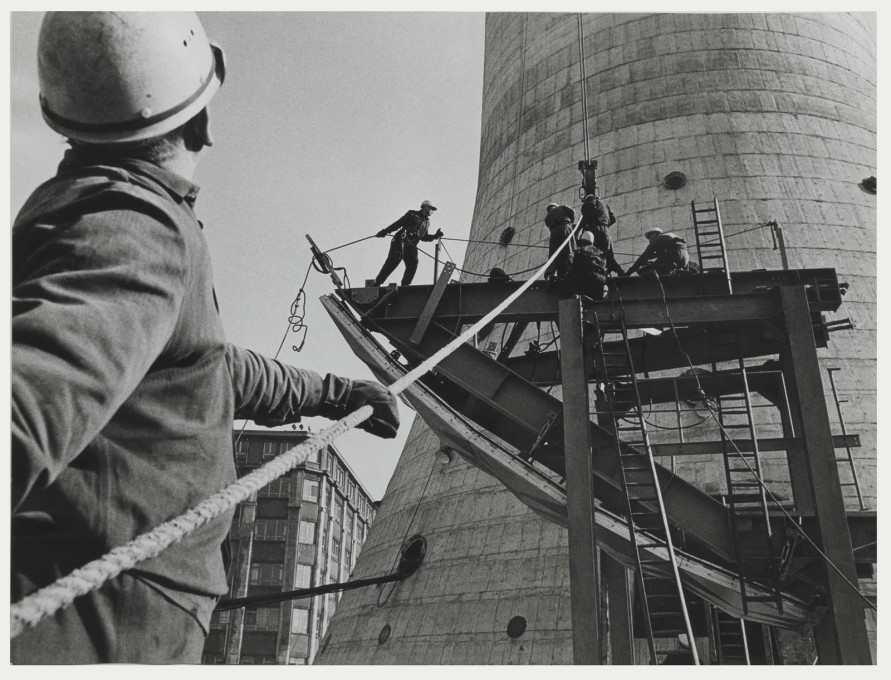

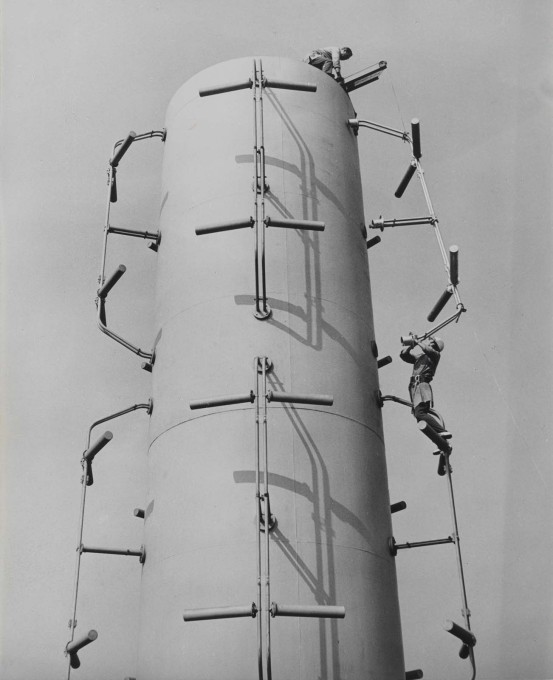

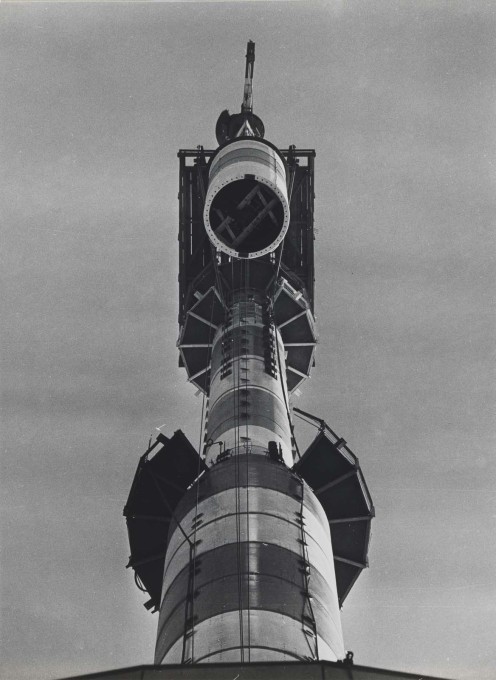

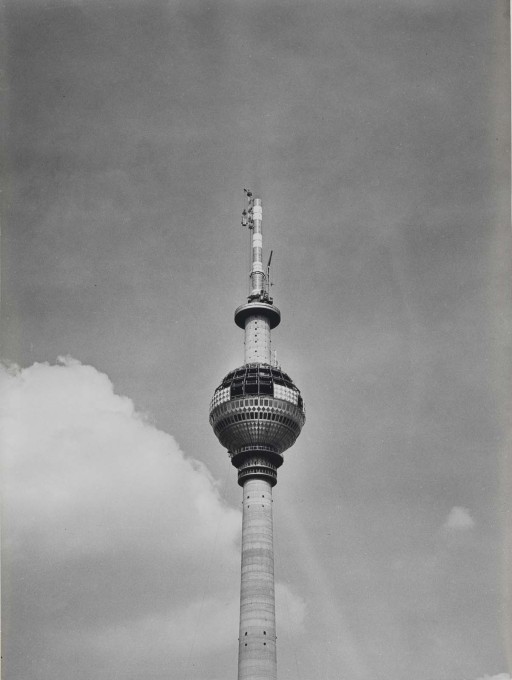

As Karl-Heinz Kraemer’s extraordinary photos show, the tower’s construction was also fittingly radical in its execution. As a former industrial powerhouse, Berlin’s skyline is even today dotted with chimneys, but this new shaft just didn’t stop growing, edging skywards between 1965 to 1969, its steel interior frame, faced by concrete bricks, tapering from a base diameter of 16 metres to 9 metres at its peak.

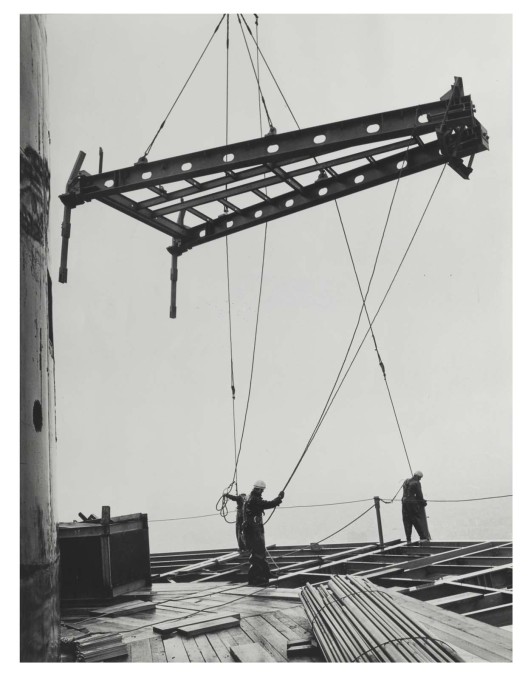

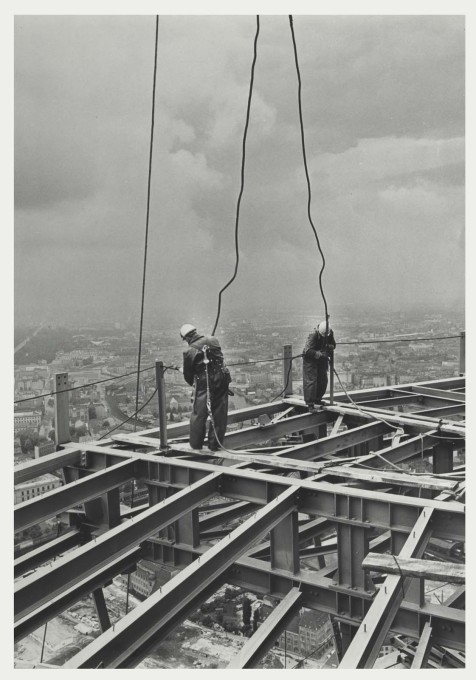

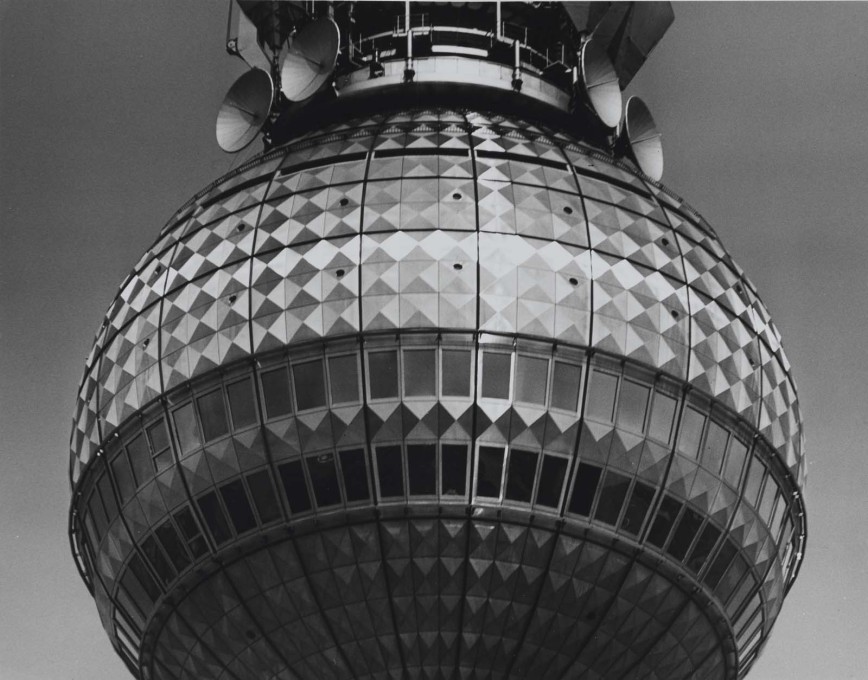

In 1967, the skeleton frame of the crowning sphere was test assembled on the ground and then dismantled and lifted up, segment by segment – 120 in all – by a lone crane which had been built in situ 250 metres above the ground. The 140 pre-fabricated steel exterior panels, which lend the sphere its space-age aesthetic, were also hoisted up into place and slotted in one by one, like a giant, futuristic jigsaw puzzle in the sky.

Space symbolism and political posturing aside, the architectural signals transmitted by the tower are similarly overt, if perhaps a little confused, employing a curious fusion of other mega-structures which encapsulated visions of a city-of-the-future – albeit under the rather different moniker of the “Democracity”: the Trylon and Perisphere of the New York World's Fair of 1939-40. Also, once built, it was realised that when the sun hit the futuristic, golden diamond-pattern motif of the sphere’s exterior panels, it caused an unplanned phenomena: the so-called “Pope’s Revenge” – producing a cross that beamed out over the communist capital of the GDR, no doubt to the authorities’ chagrin.

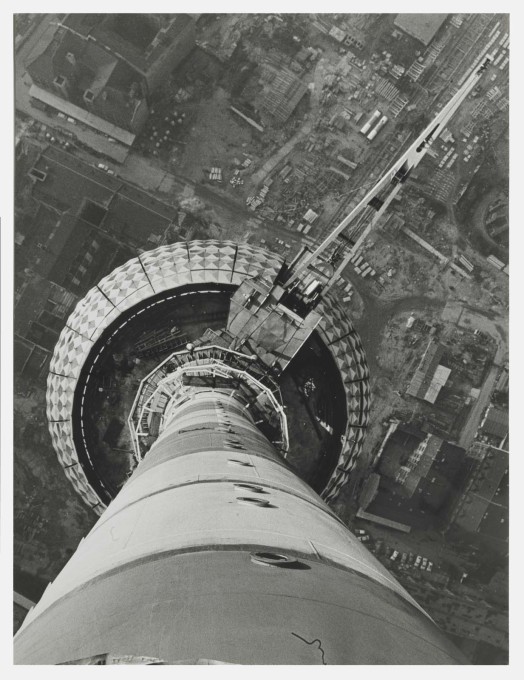

Perhaps one of the most revealing aspects of Kraemer’s photographs – and which only adds to the tower’s radically modern appearance – is not the building under construction but what lies behind: the Berlin of the 1960s, newly divided with the Wall and still pockmarked by the scars and voids from the aerial bombing of the Second World War.

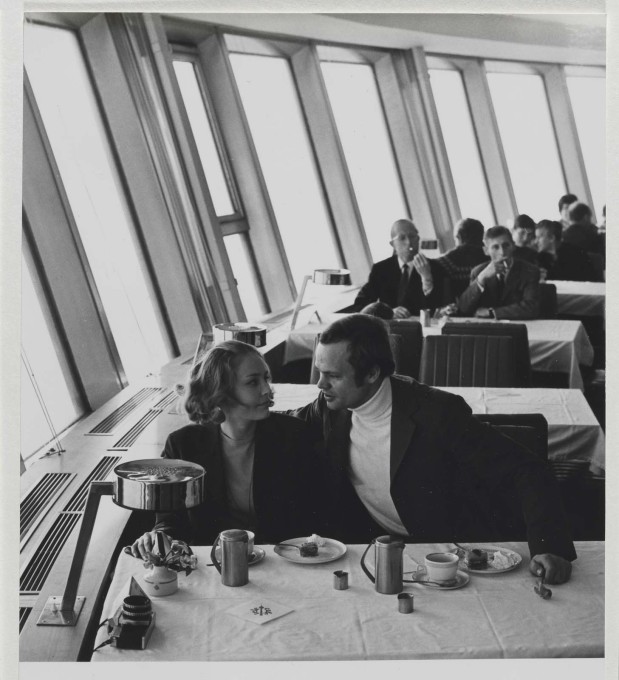

But what about the TV Tower 50 years on? The space race may be over but touches of cosmonaut chic pleasingly remain in the interior decor of the viewing deck and restaurant. And the cosmic focus on motion remains, with the restaurant still revolving, although now, following a renovation in the 90s, travelling twice as fast as it did under the communist system. This sense of historical residue extends all the way up to the calm, red pulsing of the light at the pinnicle of the tower, visible for miles. While this seems just a universally standard anti-collision light for aircraft, it has been in place since constuction, and its pinpoint of glowing scarlet can be read as a little socialist reminder of long lost might of the Soviet Bloc, still proudly blinking atop its Sputnik beacon.

The view from the top today looks down on another structure which also represents the complex layering of Berlin’s history, as well as being another architectural relic – if an ersatz one – of a lost political system: the Berliner Stadtschloss (City Palace), currently being rebuilt. This reconstruction, on the site of its original Prussian incarnation – torn down and replaced by the the GDR Palast der Republik, itself demolished in 2008 – shows how different the approach today is to reimagining the city centre, as process that seems to be looking to the past not the future.

Post 1989, there were calls to tear it down the TV Tower too, but it has not just endured, but become deeply embedded within both the urban fabric and consciousness of the city. Seen within its shadow, the rebuilding of an imperial palace seems an even more radically unmodern thing to do.

Radio signals, space signals, architecture signals and political signals: Henselmann’s concept certainly lived up to its name, but becoming today an undisputed signifier of German unity.

– Fiona Shipwright

Radically Modern. Urban planning and architecture in 1960s Berlin

until October 26, 2015

Berlinische Galerie

Alte Jakobstraße 124–128

10969 Berlin

Germany

uncube are media partners of Radically Modern. Please check the related articles, including interviews with the exhibition’s curator Ursula Müller, radical Austrian architect Georg Kohlmaier and Daniel Libeskind.