-

All illustrations by Klaus.

-

-

First things first: You're an architect, aren't you? Or at least you studied architecture at some point.

Yes, I've been a registered architect for about 15 years now. I'm getting over it, though.

I'm well aware that there are very elastic boundaries between architecture and (let’s say) beyond, but how does cartooning fit into your practice?

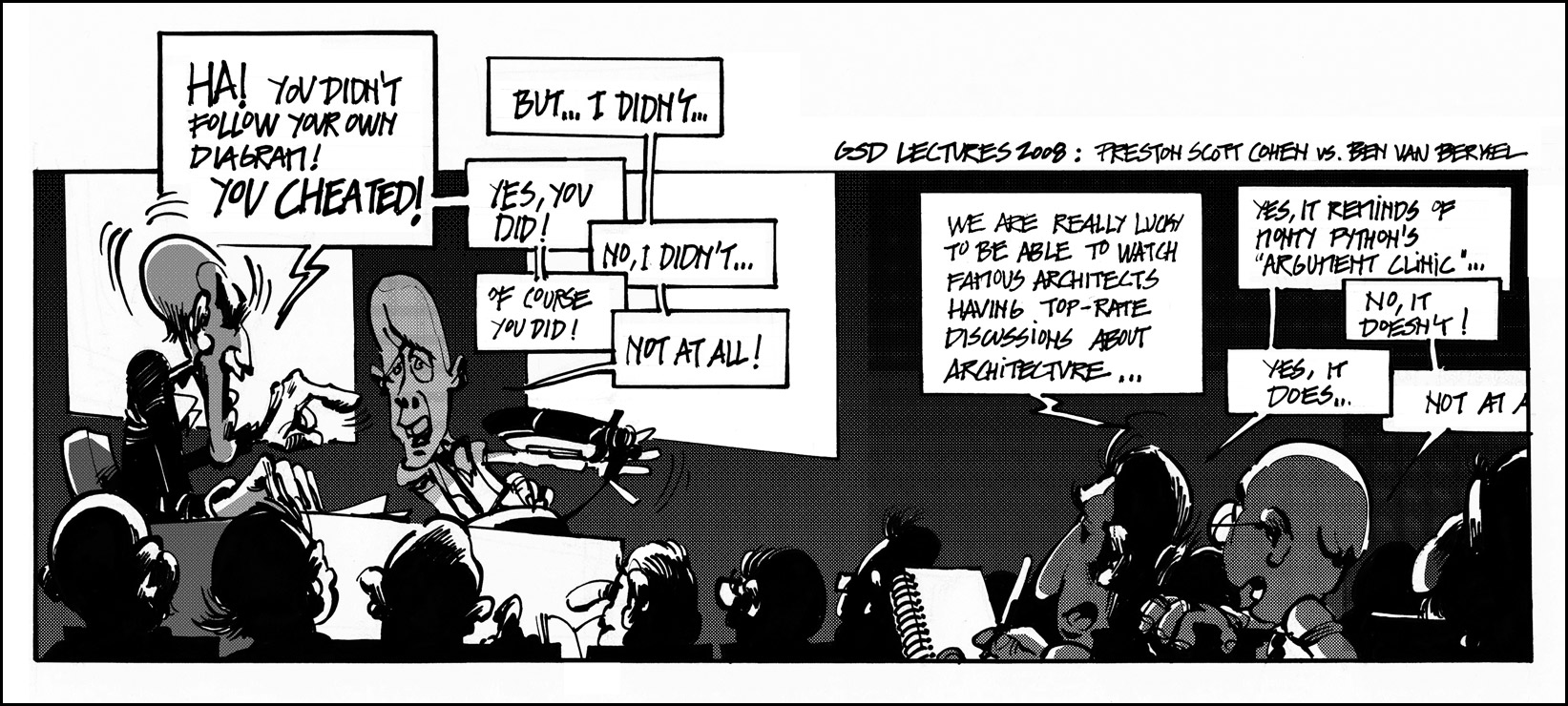

It started when I was at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD). I was about to start my PhD dissertation, which meant I was desperately looking for excuses that kept me away from it, and the GSD was a great provider of those: you had all these vedettes walking around, lots of stressed students living in their pods, loads of models piling up... it was eminently cartoon-isable. Then, one day Preston Scott Cohen had a hilarious conversation/argument with Ben Van Berkel, and I thought: “ok, I have to make a cartoon of this”. And that was that. Thanks, Preston. But, going back to the elasticity you pointed out: yes, there is definitely a lot of disciplinary promiscuity nowadays, due to the decrease in “traditional architect” work. However, I think that the 2008 crisis exposed something that has always been there. Historically, if you had drawing skills and were good at maths, you were often automatically directed towards architecture, so over time, many learnt to vent their artistic urges through architectural design... sometimes more successfully than others. I think that nowadays, many people with an architectural background are just exploring the intersections between architecture and passions they sublimated through architecture, or some other ones they discovered at architecture school.

What does it mean to be an architect, then?

Many things. Many different things, that's the point. And you don't necessarily have to be all of them. In fact, you cannot be all of them. Whenever someone brings in that idyllic metaphor of “the architect as an orchestra conductor”, I feel the urge to ask the speaker to point me towards all these orchestras waiting to be conducted. The profession – and even the discipline – is changing and we need architects specialised in different fields, or people with an architectural background in other professions.

Is that the reason why starchitecture is usually the target of your satire? Because it represents this malign understanding of the architect?

Well, yes, but also because it’s so easy to make fun of. Egocentric characters have great comedic potential, and architecture education teaches you about narcissism. Also, we love trashing those who are more successful than us at – what we’ve been told is – our own game.

-

-

So you believe in the idea of the architect as critical thinker or provocateur?

There are cases we all know where the simple ability to think would be asking too much. But yes, I do believe in the architect as an intellectual. The main problem is that we are usually taught to work with evocations: architects are great at appropriating concepts, images, strategies from other disciplines and turning them into form or discourse. This is an attitude that many of us take into whatever we do, so our approach to everything tends to be very superficial: just a hint at the surface and we begin to extrapolate. That’s why architects usually make mediocre poets and terrible philosophers (I think I'm making many friends today).

I remember listening to Peter Eisenman ranting once about the lack of “close attention” paid by today’s students; however, I think that’s something endemic to the profession. Derrida himself thought that Eisenman’s approach to deconstruction had nothing to do his own understanding of the concept. I like architects thinking out loud, but most of the time they’re just posturing, and bleating the same archibabble – or recombinations of it – again and again.

What you do in your role as a cartoonist, or caricaturist, is a quite blatant form of criticism, so are you not just hoisting yourself with your own petard?

There’s a critical attitude behind it, that’s obvious. However, I’m not trying to provide constructive criticism. I’m not even trying to be fair. There is no consistent attitude, or overall unifying discourse: I’ll criticise one thing and then its opposite. It’s all about having fun. I think you mentioned the word “jester”, at some point, which is pretty accurate, because jesters’ humour can be self-deprecating, if needed, and they are also great pranksters.

So, anything goes in your view including offence, if necessary?

Sure, although I think my cartoons are very tame, usually. Of course, I come up with much harsher stuff, but I don’t have the time anymore. My current collaborations take up most of my spare time, so I have to choose. And, believe me, you wouldn’t want to publish the things that creep inside my head. So, there: I sold out. I’ve always been very partial to money.

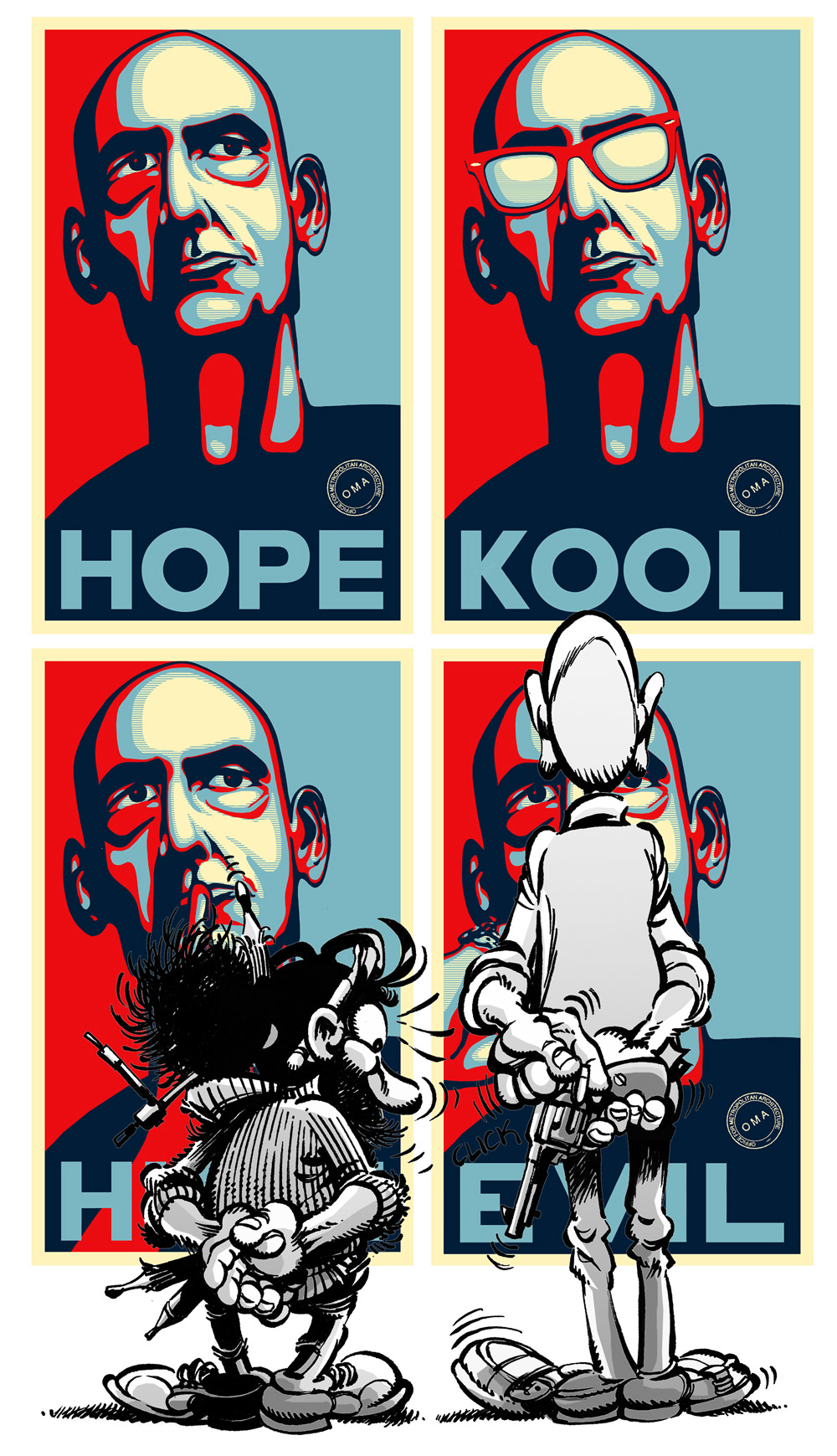

The “Kunst Haas” series, made just after the US presidential election of 2009. “Shepard Fairey hasn't sued so far” says Klaus, and hopefully Mr Koolhaas has a good sense of humour.

-

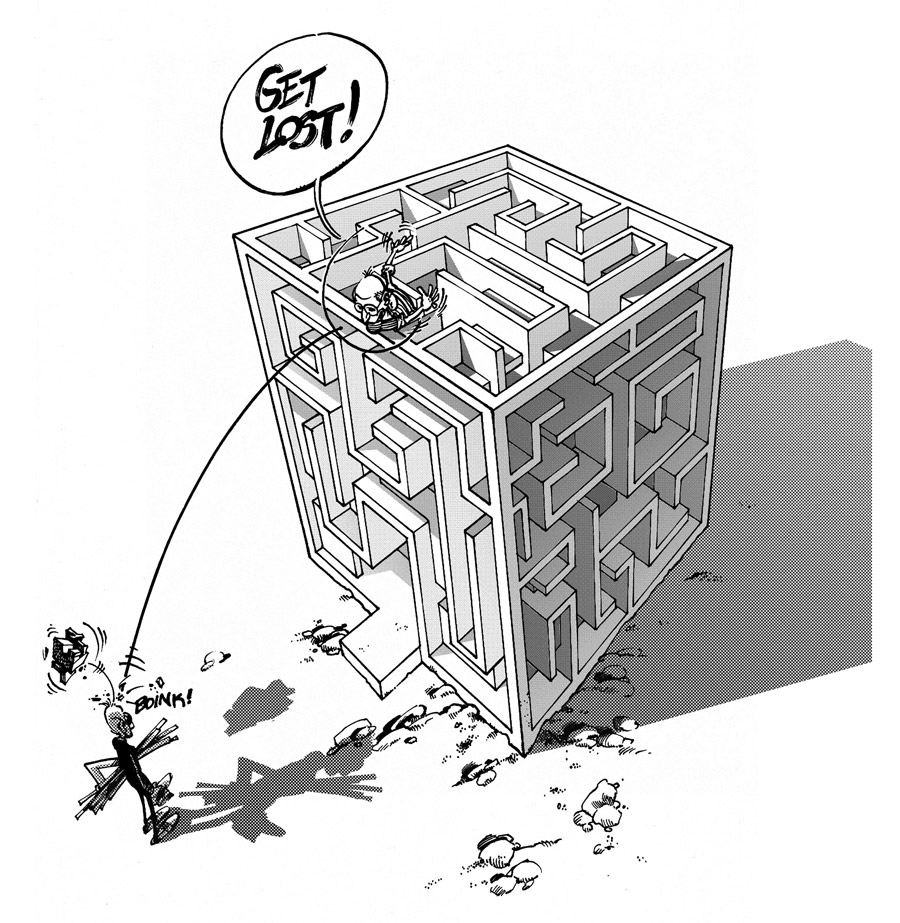

“Eisenmania, or the Corruption of the Modern” (February, 2010). One of Klaus’ many takes on Peter Eisenman and his trademark obsessions.

A colleague of yours, Jimenez Lai, said that humour, parody and exaggeration can also be very productive as form-givers, that one can tread new paths through exaggeration.

Oh, absolutely. We are not born as abstract thinkers, so we obviously learn through imitation, by copying. Some people may have abstract minds, but most of us rely on reactive mental processes, so we react to what we are shown either by copying it, negating it, twisting it (that's when caricature enters the equation). What’s interesting to me is that, if you copy something sufficiently poorly, or you take exaggeration too far, it becomes something different. Double meanings work very in much the same way: humour is mostly based on twisting words, or looking at things from a deliberately twisted angle, which may provide new, interesting perspectives that you would not come upon through realistic, or fair thinking.

I see: the hyperbolic distortion machine, architectural caricature and distortion as a design force. You’ve spoken elsewhere about the “suspended reality of the cartoon” as a freeing design environment. You certainly have a penchant for fantastic architecture/architecture of fantasy. In contrast, in your architect persona, do you experience designing actual buildings as a straight jacket?

Not a straight jacket so much as a task that requires too much effort in my case. Designing on a paper or with models and actually building something are related but they’re not the same thing and you have to be willing to invest a lot of energy. I’m less and less interested in it as time passes. However, built architecture can compensate for all the things you lose when working in the free rein of theoretical design. That said, unbuilt, or even unbuildable architecture, paper architecture, visionary architecture, whatever you want to call it, does encapsulate a inexhaustible capability for fascination. Many of us have a penchant for the visionary (not utopian, please) proposals of the 1960s, and the megastructural scene, in general. And, of course, it has to do with the fact that it was never (supposed to be) built. Almost 20 years ago I remember drooling over Zaha Hadid's book The Complete Buildings and Projects. Each of those crowded drawings suggested so many possibilities... Then she started building, then AutoCad entered her office, and that was that. Except for her stadium in Qatar – that was excellent cartoon fodder.

-

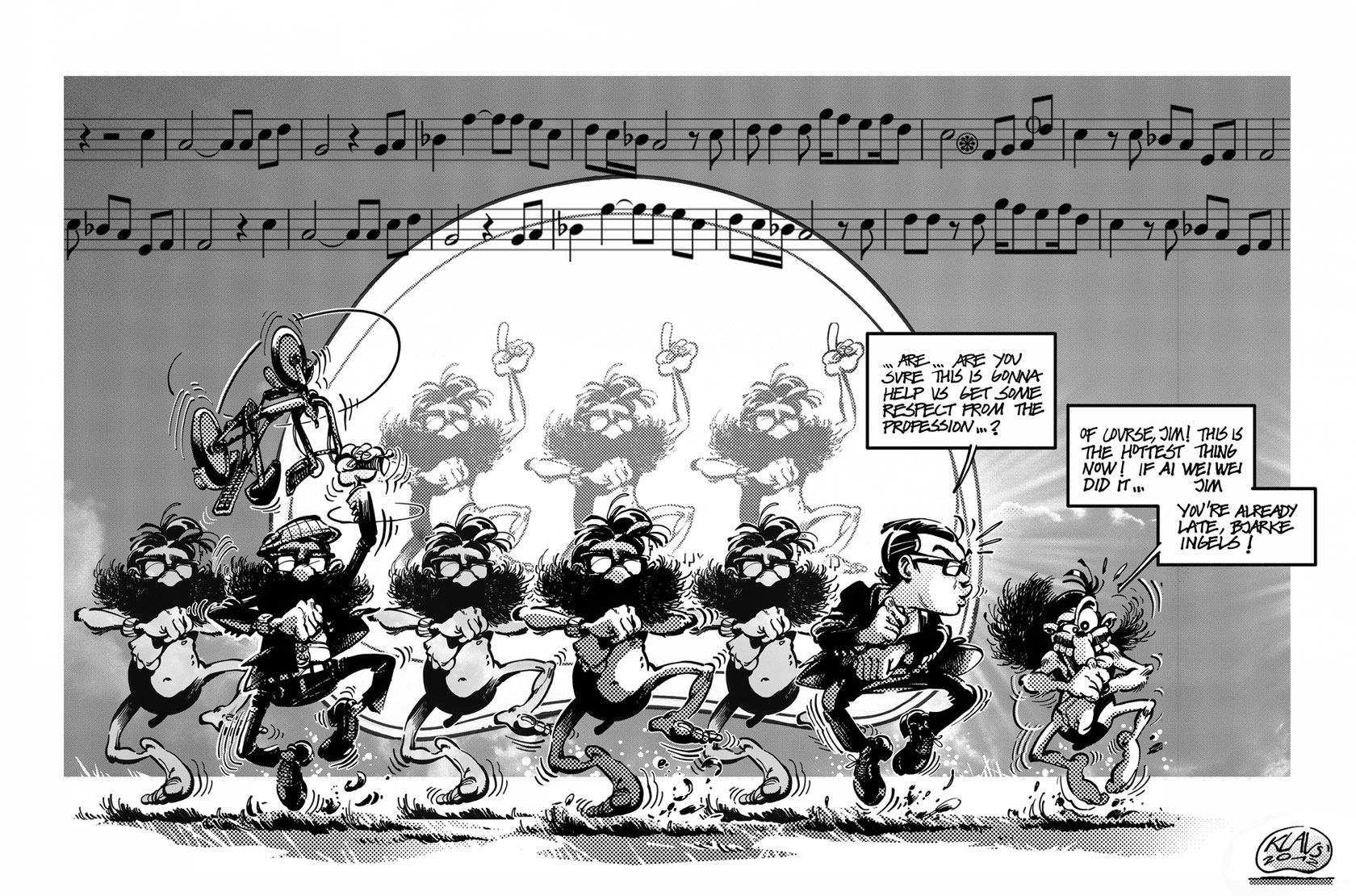

Klaus and Jimenez Lai (also featured in this issue) dance along with a bunch of Reyner Banham clones in front of the Environment-Bubble, another recurring image in Klaus’ cartoons. ('Banham Style', 2012)

-

Does being a great draughtsman make you a better architect?

No, I don’t think it does necessarily. Obviously, you need certain graphic skills to represent architecture. Also, sketching is a great way to organise and visualise your thoughts. However, having impressive graphic abilities doesn’t guarantee an equal capacity to design impressive architecture. Being too enthusiastic about drawing can even be counter-productive: a beautiful plan does not necessarily produce a good building, and if you’re too focused on making the drawing look good you may take decisions that work well for the plan as a drawing, but not for the building itself.

-

Klaus is a frustrated cartoonist who lives in an old castle in Europe, intermittently uploading his cartoons in Klaustoon’s Blog since 2009. Much to his surprise, his work has been featured in architectural publications such as A10, Arquine, The Architectural review, Clog, Harvard Design Magazine, MAS Context and Volume, among – he stresses – many others. It has also been exhibited in places such as Barcelona, Cambridge, Chicago, London, Naples, New York, Portimao, or, most rejoicingly, OMA’s canteen. He has been the in-house cartoonist of uncube since issue 7.

In his other life, he is also an architect, architectural scholar and university professor. His work, mostly focused on the unbuilt and the history of the image of the future, has found publishing within the same established media he mocks.

He is not Rem Koolhaas.

(Photo © Simone Florena)

You have been drawing under the Klaus moniker for about 12 years now. Why the pen name? Does anonymity simply give you freedom to be more critical? Or is it a way to keep different jobs in different boxes?

Both, actually. “Klaus” is an anagram of my given name. When I started publishing comic strips in an local architecture magazine, I thought it would be a good way to avoid compromising my real name with less-than-serious stuff, because I was also starting to produce academic work. Years later, when I took it up again and went online, people started contacting me as Klaus, and I started writing under the Klaus persona. I enjoyed the freedom it gave me, but also the fact that it had a very distinct voice from my official, academic fare. So I kept both personalities. We get on pretty well, as a matter of fact. And it provides nice threesomes, too.

What does Klaus’ “old castle in Europe”, where he lives, look like?

Oh, when the crisis struck, the bank took it from me. I think they’re selling it to install an Apple store.

One last question: Are you Rem Koolhaas?

No. He’s much taller. I

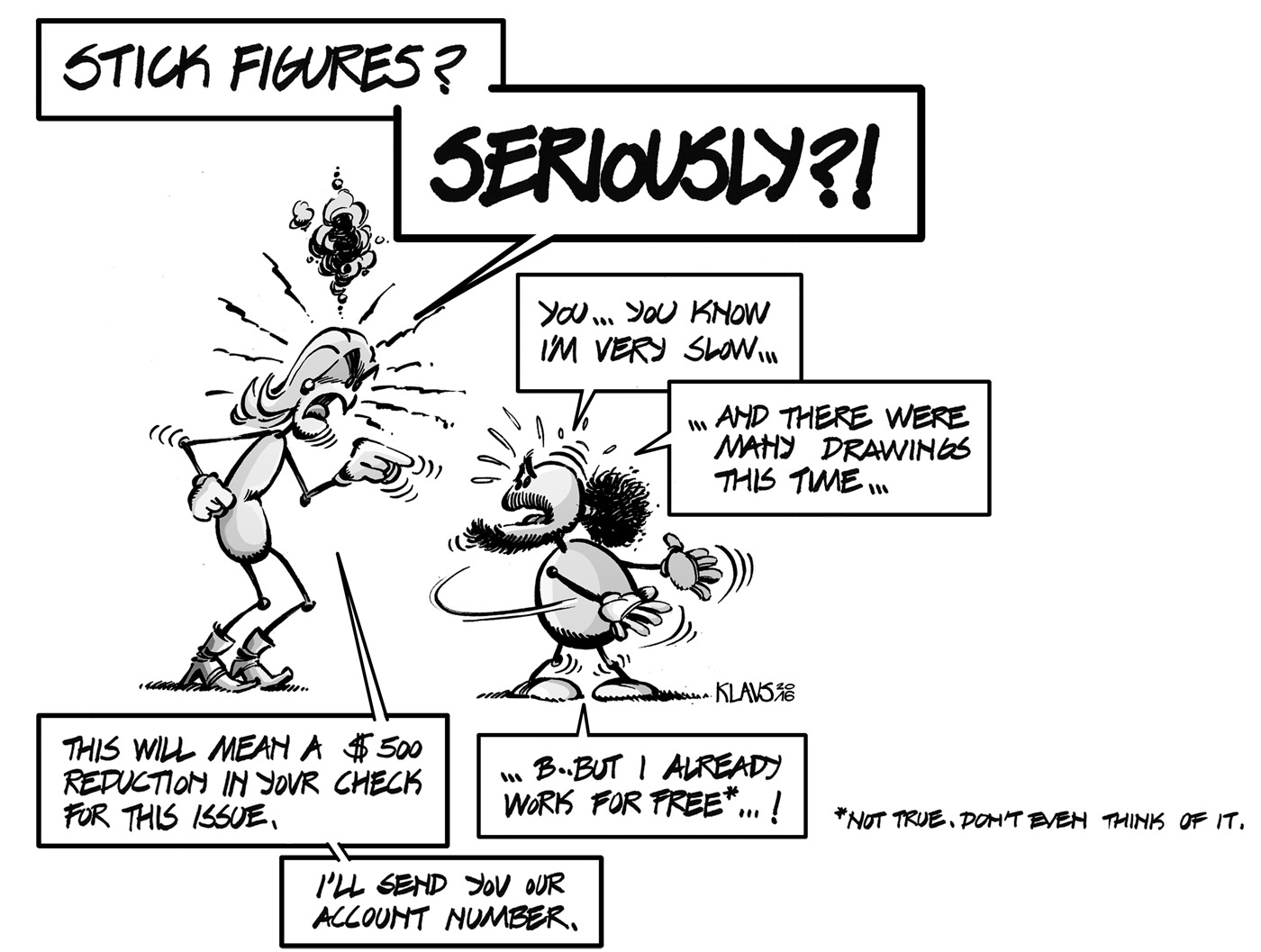

Klaus takes advantage of the liberties of the jester to the full even when it comes to biting the hand that feeds [ed.].

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Don‘t fight forces, use them.«

Richard Buckminster Fuller

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents