-

A city of shadows as architectural fiction

By Elvia Wilk

-

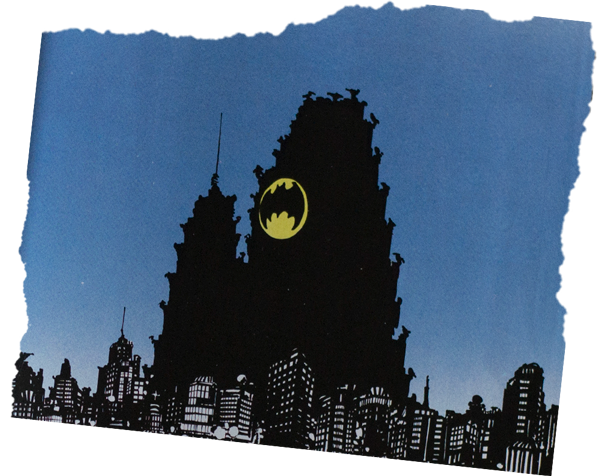

Beginning as the sum of some lines on a page, buildings usually take on a life of their own when manifest in physical form. But there are cases when whole cities manage to do that without ever having left the paper. Elvia Wilk braves the noir shadows that are the haunt of a certain nocturnally inclined caped crusader to explore a fictional city captured in ink by several generations of comic book artists. A city that very much exists in the collective memory and imaginary of millions: Gotham.

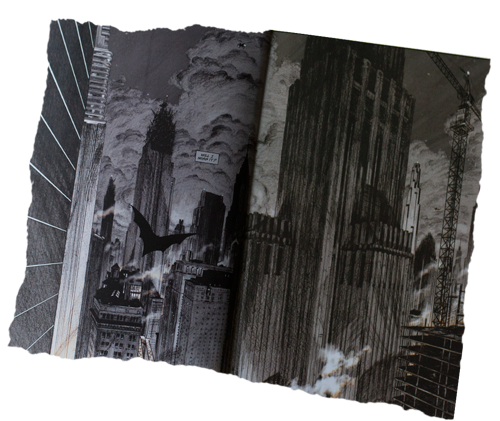

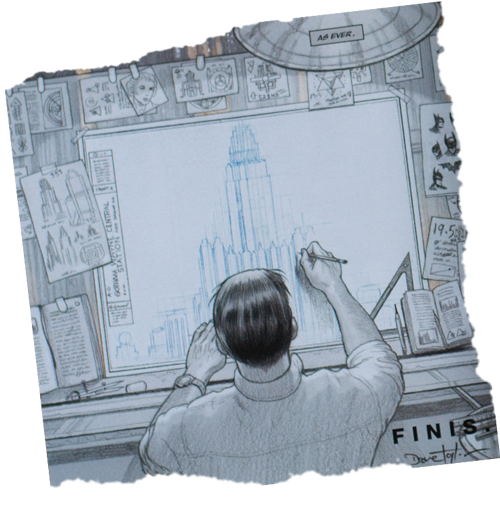

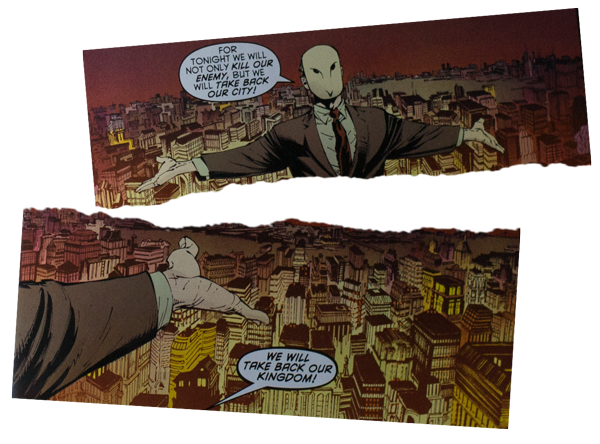

Visions of Gotham: Frank Miller, Klaus Janson and Lynn Varley (1986); Greg Capullo (2012); Chip Kidd and Dave Taylor (2012); Juan Ferreyra (2015) . Collage by Janar Siniloo.

-

In The Dark Knight, the second movie of Christopher Nolan’s high-budget Hollywood trilogy resurrecting Batman’s classic storylines, the masked hero announces during the final climactic scene: “I’m whatever Gotham needs me to be.” From Batman’s earliest comic book days in the 1940s to the multimedia DC franchise in the twenty first century, the caped crusader has been synonymous with his city. Gotham is the place he loves and protects, and it’s also the place that constantly thwarts his heroic attempts.

The nickname of “Gotham” was applied to New York City long before DC Comics picked it up. The moniker was first introduced by the American author Washington Irving, who used it jokingly in reference to a village in England of the same name, said to be inhabited by “fools”. In other words, Gotham is the fool’s New York, the city of two-faced con artists and tricksters perhaps best personified by Batman’s arch-adversary the Joker. The architecture of Gotham, as depicted by countless comic book artists, represents and relies on the sinister aspects of early Manhattanism, the shadowy side of those grand visions of what a city could and should be. As DC Comics artist Frank Miller is reputed to have said: if Metropolis (the home of Superman) is New York by day, then Gotham is New York by night.

-

Detail from “Founded on Insurance” by Hugh Ferris (c.1929). (Image courtesy the Tchoban Foundation)

-

It was the striking early twentieth century drawings of artist Hugh Ferriss that in many ways planted the seed of the collective visual imaginary of Gotham. In his artwork one can see a certain link between Batman’s city and the residues of modernism. Ferris, who originally wanted to be an architect, was disappointed by the lack of ideological purpose in the profession, and he decided to become a renderer instead, drawing his future ideals instead of dwelling on contemporary realities. In the early 1920s he moved into an artist studio and was creating not only renderings for architectural offices in his soft, blended Conté crayon style, but dramatic visions of Manhattan on oversized canvasses.

The effect of Ferriss’ aesthetic cannot be underestimated – not just on the DC Comics universe, but on urbanism itself. Rem Koolhaas went as far as to call his idea of space the “Ferrissian Void”, a phantasmagoric envelope for any design vision (or superhero storyline) to be projected upon. But Koolhaas also called Ferriss “Manhattanism’s automatic pilot”, and even “the Master of Darkness”– a blind devotee of modern architecture whose art “remains subconsciously critical”. What Ferris thought he was showing (the brilliant utopian future) was not what we see now in his work, and which has since been picked up on by generations of comic book artists: a steamy dystopian zone where covert action goes down in back alleyways, the negative spaces either misused or unaccounted for by the master planner.

-

Ferriss’ expressionistic sketches tell us what modernism was meant to feel like – monolithic, singular of vision, maximal, and unadorned – but Batman’s Gotham is no modernist city of glass and steel. It’s uneven and post-industrial, with neoclassical remnants of crested, crumbling brick façades wedged alongside gleaming skyscrapers. It is undoubtedly a city where the authorities haven’t been able to control growth, and the modernists haven’t won out against the rise and decline of industry or managed to erase the layers of architectural history. Batman’s Gotham may be highly futuristic, but it’s also deeply nostalgic.

Though Gotham is a clear expression of Manhattanism gone rogue, the question of whether Batman’s city is indeed New York is hotly contested. Some, like comic book artist Neal Adams, think Chicago is a more likely urban comparison, with its varied architecture and gangs of mobsters. Others see in the geography a clear echo of Newark, New Jersey. (Christopher Nolan shot parts of The Dark Knight Trilogy in all three of those cities.) But as most comic book aficionados understand, Gotham is both nowhere and everywhere: it is not a city or even the city as such – it is the shadow of the city. It is the metropolis that, despite all efforts, cannot be planned or accounted for. The best artists of architecture, from Piranesi to Ferriss to Lebbeus Woods, have all shown us ideals of architecture not in presence but in relief, in the shadow of the image. It is only by being shown the shadows of our possible futures that we are able to decide whether we want to build them or not. I

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Architectural interpretations accepted without reflection could obscure the search for signs of a true nature and a higher order.«

Louis Isadore Kahn

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents