-

Magazine No. 08

Culture & the City

-

No. 08 - Culture & the City

-

page 02

Culture & the City

-

page 03

Editorial

-

page 04 - 19

Culture and the City

On Content and Form

-

page 20 - 21

Cathedral of Culture

Tate Modern

-

page 22 - 24

Grand Informal

Palais de Tokyo

-

page 25 - 26

A Spoonful at a Time

Detroit Soup

-

page 27 - 35

Containers Without Content

The disastrous roll-out of the Bilbao Effect across Spain

-

page 36 - 37

Pebbles in the River

The Guangzhou Opera House

-

page 38 - 41

Beacon for Learning

Parque Biblioteca España

-

page 42 - 53

The Island of Happiness

The shadowy story of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi

-

page 54 - 56

Fashion Forward

West Kowloon Cultural District Master Plan

-

page 57

Klaustoon

-

page 58 - 59

Bookmarked

-

page 60

Next

Constructing Images

-

-

uncube's editors are Elvia Wilk, Florian Heilmeyer, Jessica Bridger, and Rob Wilson. uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online magazine covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

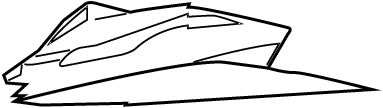

uncube No. 08 is all about the big Cs: Culture and the City, two phenomena with a chicken-and-egg relationship. In recent years – especially in the backdraft of Gehry’s Bilbao – culture has often been prescribed as a general panacea for cities, curing all ills and transforming a city’s image. But there are often unintended side effects.

This issue is a cooperation with the Akademie der Künste in Berlin and its major current exhibition, Culture:City, curated by Matthias Sauerbruch. We feature a range of very different projects, mostly taken from that exhibition, to illustrate the many ways in which culture and architecture come together in the city – for better or for worse. With Matthias Sauerbruch, William JR Curtis, and Ann Lui, we take you from the Greek polis to the Metropol Parasol, and from Venice to Gehry’s new Guggenheim in Abu Dhabi.

Welcome to uncube city..!

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Cover image: Iwan Baan

-

![]()

Culture

and the

CityOn Content

and FormText by Matthias

Sauerbruch -

Matthias Sauerbruch, curator of the Culture:City exhibition at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, explains the project’s background and the complex pas de deux of culture and the city.

![]()

Matthias Sauerbruch. (Photo: Kalle Koponen)

-

Culture is what distinguishes us from animals. Etymologically derived from the Latin verb colere – “to cultivate” or “to care for” – in its broader sense it is understood as the sum of the traces that people continuously create and leave behind in their dealings both with each other and with their physical environments. Culture refers to the collective accomplishments of civilization, and provides, first of all, the ethical and moral context in which we operate. It reveals itself, among other things, in our political and judicial systems that define the freedom of the individual and the powers of the community. The term culture also denotes the built, the human-made environment in all its aspects. Culture manifests itself in the values by which we live our lives and the forms – the things and patterns – that surround us. We also use it to designate all those activities dedicated to the further development and ongoing maintenance of the accomplishments of civilization, such as religion and philosophy, technology, science, and art: in this, culture is always anchored in the collective. It is a distillate of mindsets, manners, conventions, and moral values. The output of any given artist or author becomes culturally relevant only in dialogue and resonance with the public sphere. In addition to its various external particularities, this distillate that is culture is, in fact, the most important

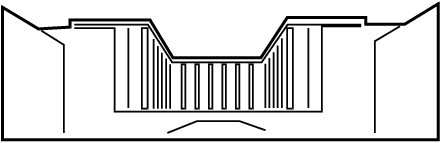

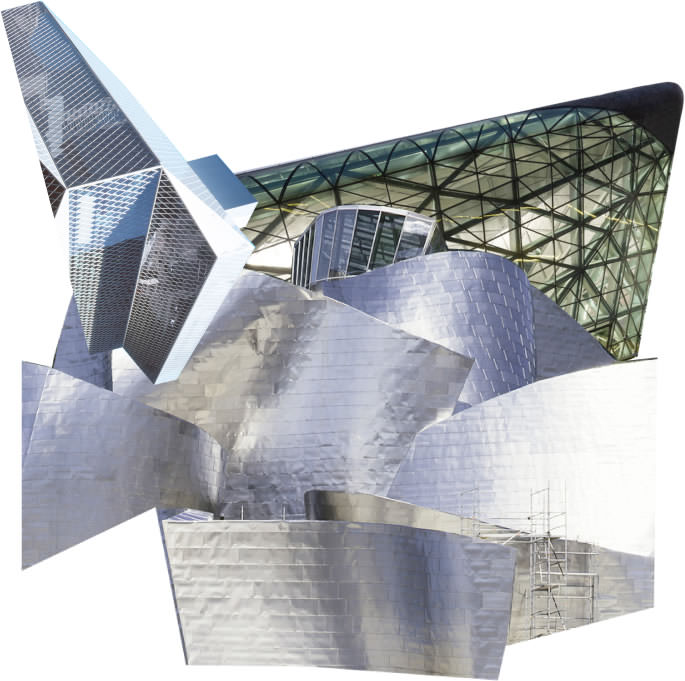

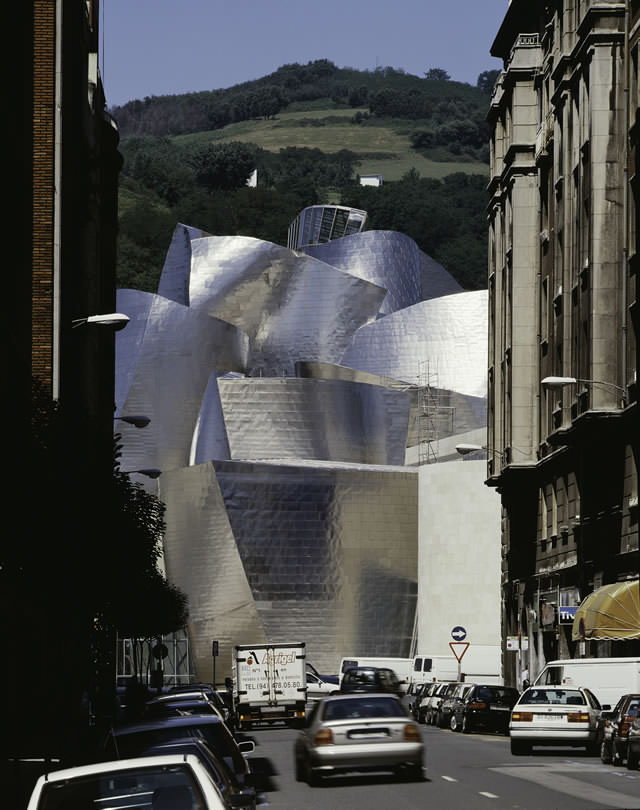

![]()

Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao: is this where it all started, this worldwide yearning for big-scale, extravagantly-formed cultural buildings? Sauerbruch says the focus of his Culture:City exhibition lies on the “post-Bilbao strategies that strive for closer integration of cultural institutions into the social structures and creative networks of a city.” (Photo: David Heald, © Solomon Guggenheim Foundation)

-

»A cultural building is no longer seen as the expression of common will, but as just one event among many, designed to fulfill some demand that may yet be generated.«

Michael Maltzan’s Inner City Arts project (the white building at the bottom of this picture) in Los Angeles could be seen as the opposite of Gehry’s Guggenheim. Carefully developedin stages over a period of thirteen years, it features no spectacular forms and integrates existing buildings. Initiated by a local grassroots initiative in one of the poorest neighborhoods of LA, it offers the young and the at-risk the opportunity to develop artistic skills. (Photo: Iwan Baan)

-

distinguishing characteristic for different ethnic groups, nations, and other forms of community. It is through participation in the ritual manifestations of their common culture that members of such groups develop their sense of affiliation and identity. On the other hand, culture also provides room for the fundamental human desire of self-expression. Independently of whether people’s sense of identity is primarily shaped by the collective, or, vice versa, communal culture comes into being through the creative work of individuals, it is clear that culture makes the space for the development of the individual as it simultaneously defines its limits.

The City and the Loss of the Public Sphere

The city is many things; most of all, it is the locus of the community, if at first only one of purpose. In both form and content the city is the most public manifestation of those aspects known as culture – it embodies our cultural memory at the same time it is the place of culture’s continuous renewal. The majority of those phenomena that we connect with the idea of culture stems from elements of the city, with which they are effectively synonymous. The polis offered the agora, the bouleuterion, the temple, the theater, the stadium, as those places where the respective community’s sense of identity was created and physically manifested.

»The city is many things; most of all, it is the locus of the community, if at first only one of purpose.«

-

Peter Cook and Colin Fournier designed Graz, Austria’s new Kunsthaus as an amorphous form that starkly contrasts with the inner city. The Berlin-based architects of realities:united conceived façcade of the spaceship-culturehouse to become a giant low-resolution screen, bridging interior with exterior. (Photo: Universalmuseum Johanneum, Christian Plach)

-

Subsequently such places became topoi that, even today, color our notions of both city and culture. These developed into architectural typologies still to be found in every city, effectively consolidating the preconception that politics happens in parliament, religion in church, and culture in the theater, concert hall, or museum. Such necessary coincidence of cultural activity with institutions was already thrown into question in the nineteenth century, but, even when the generation of 1968 – in its rejection of all forms of establishment – demanded that culture should happen in the street, it was still taken for granted that this should take place in the city.

Today, culture is still seen as being located in the public realm, but – at least since the ubiquity of television – the city and the public sphere are no longer assumed to go hand-in-hand. Culture has claimed its own rather effective space in various media: on TV and across the internet, all cultural production is widely disseminated with a previously unimaginable density and impact, and is generally independent of location. Such dissemination is known as “content” in internet jargon, and it does not in any way pass through the filter of the collective. At best it expresses swarm intelligence, disappearing without a physical trace. In this way the internet would destroy the city in the same way that Victor Hugo predicted the book would destroy the cathedral, disrupting the age-old symbiosis between collective space and culture. With the loss of this tangible public space, as Richard Sennett explains in The Fall of Public Man, the specificity of public life is characterized by an increasing focus on the individual.

![]()

M9 is a museum currently under construction in Mestre, Venice, designed by Matthias Sauerbruch and Louisa Hutton. The new building connects to parts of an old cloister and an office building from the 1960s. (Image: Sauerbruch Hutton Architects)

-

»The city and the public sphere are no longer assumed to go hand-in-hand. Culture has claimed its own rather effective space in various media.«

M9, a new museum for Mestre/Venice, to be completed by 2015. Image: Sauerbruch Hutton Architects

-

Instead of the ideas and ideals of a community, it is the mental state of the individual that demands all the attention. Sennett talks of the “tyranny of intimacy.”

These developments have lasting consequences for the city (as we used to know it). Deprived of traditional content, collective spaces begin to feel like empty shells that have difficulty relating to the random collection of vested interests by which the city seems increasingly to be defined. A new (cultural) building is no longer primarily seen as the expression of common will, but as just one event among many, designed to fulfill some demand that may yet be generated. The void left by the disappearance of active public life is filled by an ever-expanding cultural industry that endeavors to satisfy our desires for some sense of self-determination and selfexpression. Culture is no longer allowed to develop – culture is manufactured, and the commercialization of this, our need for identity, is growing unabatedly, as Richard Florida explains in The Rise of the Creative Class.

Cultural Activities and Surrogate Acts

Perhaps Venice can be used as a case study to exemplify these developments. Currently some 40,000 Venetians are responsible for the upkeep of the historic city-center’s growing infrastructure to the benefit of some 20 million visitors a year. The churches and palazzi, the impressive Arsenale – all outstanding expressions of urban culture – now stand empty and have to be filled with new commercial uses, if only to stop them from falling down. To us, of course, the protection of these historic monuments seems essential, because these buildings stand as irrefutable proof of the existence of a great culture, in which we see ourselves as participants. However, it is obvious that a short encounter – say, as part of a Mediterranean cruise or a visit to the Biennale – can never be more

-

»Essentially, the city remains the most important manifestation of culture.«

Guangzhou is China’s third-largest city. In recent years it has been trying hard to change its image from that of a booming industrial town into that of a city of ecology and culture. Part of the urban transformation along the river is its new opera house, designed by Zaha Hadid Architects. (Photo: Hufton + Crow Photographers)

-

than a surrogate act. Here culture becomes a cliché, just a selling point and marketing device, the experience of which rarely goes beyond mere consumption, and doesn’t offer any impulse to contribute much in return. For the twenty million visitors that Venice attracts every year this does not present a problem, since, in any case, they will soon return to their own homes; but for the Venetians the problem is acute as their local culture becomes fully submersed under the nostalgia of their own past; thus residents are condemned either to an existence as amateur actors restaging their own history, or to being tourists in their own city. In this way contemporary Venetian culture manifests itself, if at all, either in the form of resistance to the ruthless marketing of the island, or simply in relocating itself to other, more impartial sites, such as Mestre on the mainland.

Venice is, perhaps, an extreme case, but the culture of many other European cities also finds itself in a somewhat similar process of development. Where historic fabric still exists, it becomes the scenic backdrop for rigorous commercialization. Traditional city centers line up alongside amusement parks, shopping centers, sports facilities, and commercial zones as just one of many urban events embedded in an extensive network of infrastructure. Telecommunication and unlimited mobility have blurred the traditional territories of European cities, just as globalization and structural change have modified their economic foundations.

![]()

“In the race for the fleeting attention of the internet generation,” writes Sauerbruch, “the architectural profession has also allowed itself to be tempted into ever-increasing extravagance.” Guangzhou Opera House, main auditorium. (Photo: Hufton + Crow Photographers)

-

OMA’s library offers a system of freely accessible public space spreading over all floors of the building, culminating in a spectacular reading room with panoramic views on the top floor. Since its opening in 2004, the library has become a favorite hang-out place for youths and homeless – it has about 8,000 visitors each day. (Photo: Philippe Ruault)

-

![]()

Seattle’s public library by OMA − in collaboration with LMN, 2004 − has become an icon for public education. (Photo: Philippe Ruault)

-

The Architect as Agent

In the context of the city in metamorphosis and a culture industry that is increasingly alienated from its own roots, the Culture:City exhibition that I’ve curated at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin explores the potential provided by selected architectural interventions with cultural intent from the last thirty years. It describes the dilemma of architects and clients building for a community of consumers who participate, at best, in a critical role. Challenged to provide an appropriate spatial and architectural setting to express what people might consider to be the essence of contemporary culture, they need to invent formats for content yet to be found – risks and issues in design that the exhibition explores. Projects from recent years seem to oscillate between market-oriented gestures and a desire for authenticity, between attempts at developing inherited traditions or doing justice to new situations. By obvious virtue of their longevity, buildings can significantly strengthen the presence and continuity of culture, but in the race for the fleeting attention of the internet generation, the architectural profession has also allowed itself to be tempted into ever-increasing extravagance. The overview provided by the exhibition highlights the difficulties involved in building effective social spaces. As the community seems to have lost the impetus to adopt its role as a client, architects become its involuntary agents – a role that seems to overwhelm them in many cases.

![]()

Before the Guggenheim Bilbao, one of the world’s main reference points for large-scale cultural buildings in a historic city was the Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris 1977) by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers – though it didn’t drastically change the image of Paris. (Photo: Renzo Piano Building Workshop)

-

Matthias Sauerbruch studied at the Hochschule der Künste Berlin and the Architectural Association in London. In 1989, together with Louisa Hutton, he founded the firm Sauerbruch Hutton in London, and since 1993 the main office has been based in Berlin. Beyond his work as an architect, he has taught at the AA and been professor at the TU Berlin and the Stuttgart Akademie der Bildenden Künste. From 2006 he has been a visiting critic at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and since 2012 a visiting professor at the Universität der Künste Berlin. He is a founding member of the German Sustainable Building Council, a commissioner of the Zurich Building Council, a trustee of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, a member of the Berlin Akademie der Künste, and an Honorary Fellow of the American Institute of Architects.

Culture:City (Kultur:Stadt)

15 March - 26 May 2013

Tue-Sun 11am to 7pm

Akademie der Künste

Hanseatenweg 10

10557 Berlin

On the other hand, across a wider perpective, judicious interventions, large and small, can be shown to create a new self-awareness, helping moments of new urbanity to develop in unexpected ways.

Closing Remarks

While the projects shown in Culture:City document the rise and fall of the “Bilbao effect”, its main focus lies in those post-Bilbao strategies that strive for closer integration of cultural institutions into the social structures and creative networks of the city. These are strategies whose physical presence not only offers a landmark for effective marketing, but provides, above all, urban reservations that hold the potential for diverse cultural activities. Here culture and urban sophistication need not be manifested in the invention of ever-new experiences, but essentially in an appropriateness of how something takes place – even if it is only a banal everyday activity. In this sense cultural places can be anywhere, but they have to be created, and their inventors need intuition, empathy, courage, and endurance, as well as a certain readiness for sacrifice; because they are fighting against the inertia of habit and are under constant risk of failure. Here architects have found themselves in a strange role, serving as a kind of glue between bottom-up and top-down, working as privately funded executors of the collective interest and producing artifacts that are a tool for and an embodiment of culture, both enabler and memorializer at the same time. All this happens in the context of shrinking resources, a constantly diminishing economy of attention, and fierce competition between cities and institutions. Despite all this, the built environment, essentially the city, remains the most important manifestation of culture, and it is the tangible expression of our idea of coexistence. To maintain, protect, enrich, and refine this city is the noblest task of all of us, not just for those immediately involved in planning and building.

![]()

-

Cathedral

of Culture(Images courtesy Herzog & de Meuron)

![]()

-

In 1994, Tate Gallery, previously known for its focus on British Art, purchased the redundant Bankside power station as a new home in which to house and extend its contemporary art collection. The competition to redesign the building was won by Herzog & de Meuron with an elegantly simple proposal, keeping the existing structure largely intact. The architects were sympathetic to the building’s former use, intelligently combining old with new: so the newly constructed interiors, lined in polished concrete and untreated wood, preserved the industrial charm of the original, whilst lending themselves well to the art gallery experience.

Today, the Tate has become one of the most popular art institutions in the world – thanks to the gallery’s programme, but also perhaps to the architecture too. The reuse of this huge industrial dinosaur as a place for culture has made it an icon for London and a model for post-industrial reinvention in cities worldwide.

This success has led gallery director Nicolas Serota to commission the same architects to build an extension, due for completion in 2016. The almost archaic-looking pyramidal design cues off the original building with its brick-clad façade, yet also acts as a contrasting monumental form: in keeping yet distinctively contemporary.

![]()

![]()

Video: “Rejoice (Tate Modern).” Director/cutting: Julia Langhof, camera/cutting: Michael Grabowski. This short movie was exclusively produced by students of the Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin (DFFB) for the exhibition “Culture:City” at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin (2013).

![]()

-

Grand

Informal

(Images courtesy Palais de Tokyo)

![]()

-

Stripped down neoclassical has a grand scale and an unpretentious interior appearance – formal exterior attitudes reveal a deliciously informal interior. This is the aesthetic of the Palais de Tokyo, a space for creative work. The structure near the Seine in central Paris is impressive. Created for the 1932 Paris International Exposition, the building was transformed through minimal means – reducing superfluous interior divisions and making one small addition – by the Parisbased team of Ann Lacaton and Jean Philipe Vassal. The new raw-seeming space, easily configured to suit nearly any kind of event, houses the site de création contemporaine, a progressive institution with a freewheeling cultural program and method of engagement with the public. A garden by atelier le balto (uncube favorites) beside the building provides a respite from the hustle-bustle of other more formal outdoor spaces nearby, expanding further the flexible program possible at the Palais de Tokyo. (jb)

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

A

Spoonful

at a Time(Photos: David Lewinski)

![]()

-

Projects that are part of the popup phenomenon – where everything from medical clinics to Michelin-star quality restaurants temporarily open and provide a limited service – are often extremely short-lived. Detroit Soup, a project by artists Kate Daughdrill and Jessica Hernandez, takes a pop-up soup restaurant – $5 a bowl – and infuses it with a community flavor through using the proceeds to partially underwrite local public projects that are presented and voted on at the lunch. This is bottom up action, spooned slowly into the city. Detroit’s difficult position as a shrinking city has led to a range of creative initiatives to respond to economic blight with cultural production. Detroit Soup tries to create micro-scale interventions through something as simple as sharing a meal and ideas, adding to Detroit’s slowsimmer of rethinking challenging urbanities. (jb)

![]()

![]()

Video: “Detroit Soup.” Director/camera/cutting: Theo Solnik. This short movie was exclusively produced by students of the Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin (DFFB) for the exhibition “Culture:City” at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin (2013).

![]()

-

![]()

Containers

without

ContentThe disastrous roll-out of

the Bilbao Effect across SpainText by

William J. R. Curtis -

We have heard ad nauseam that “culture” in a post-industrial society is an essential part of the economy, a bartering device with which cities can establish a “brand” in the globalised networks of information, entertainment and tourism. Like everything else in the world of mass consumerism, from cars to supermarket food, the emphasis shifts from function and substance to packaging and image. Here the essential model is the advertising clip which may, for example, associate a brand of coffee with a well-known actor, or suggest that a scent and its shapely glass container will promise erotic conquests and delights. In the case of marketable museums and cultural centres, the image has to be instantly recognisable on the computer screen or in the airport magazine. Architecture is reduced to being a flashy container without much content to it.

»The image has to be instantly recognisable on the computer screen or in the airport magazine. Architecture is reduced to being a flashy container without much content to it.«

In Spain, no doubt under the spell of the so-called Bilbao Effect, mayors and civic authorities have stumbled over themselves to link their provincial cities to the delusory “global economy” by employing members of the international architectural star system to perform magic tricks for them without enough thought for real need and long-term cost. What the actor has done for coffee, the architect is supposed to do for the local economy by attracting attention with iconic buildings and hooking into networks of official cultural power, many of them in the dubious world of the institutionalised avant-garde, itself a commodity in the financial operations of the art market. Curators are expected to buy the latest approved products in art fairs and biennials and then distribute them in their showrooms and containers (museums and cultural centres), where the public is expected to consume them.

-

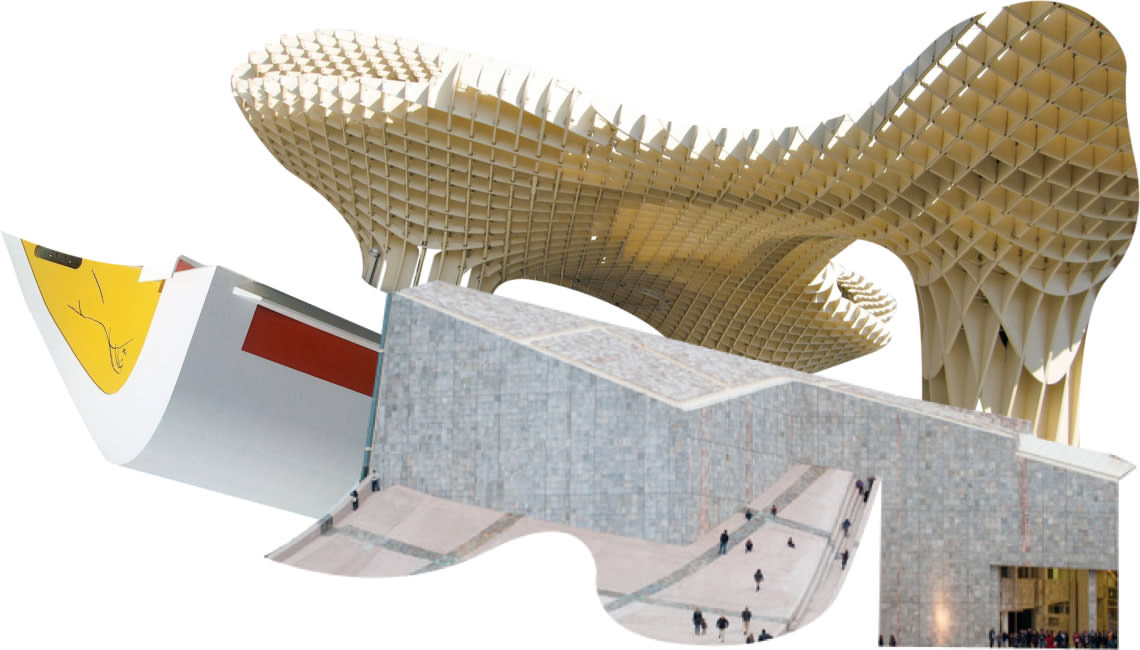

The walkways that snake across the top of Jürgen Mayer's Metropol Parasol provide panoramic views over the roof-tops of Seville. It is one of the largest and most complex wooden structures in the world, every piece of laminated timber in the waffle-grid construction unique in form, joined by steel bars and a specially-developed glue – giving it the flexibility to expand and contract in the extreme summer temperatures of the city. (Photo: David Franck)

-

All of this is supposed to be for the public good, there being the implicit suggestion that Spanish cities are without any intrinsic cultural value of their own until irrigated with this sort of investment. The architect responsible for the container is supposed to supply an attractive setting through formalistic demonstrations while the local culture is “themed” and reduced to caricature for tourist entertainment. The computerised image and fast-track production assure instant icons that are supposed somehow to give identity to this or that place, a preposterous suggestion for cities centuries old. Geometric gymnastics are the order of the day and Spanish cities are now littered with narcissistic exercises, such as the Metropol Parasol scheme designed by Jürgen Mayer for the Plaza de la Encarnación in Seville, a series of giant techno-kitsch mushrooms that effectively destroy a historic urban space while partially privatising it.

![]()

![]()

Situated in the redeveloped market square of Plaza de la Encarnación, Metropol Parasol is known locally as “Encarnación’s mushrooms.” It has four different levels: below grade a museum displaying the archaeological remains on the site; at ground level a market; above an elevated plaza; and on top of the structure, panoramic walkways, terrace and restaurant. (Left: Rafael Gomez-Moriana, criticalista.blogspot; Below: David Franck)

-

»The City of Culture of Galicia, designed by Peter Eisenman, sums up the excesses of the system with its empty rhetoric and extravagant and meaningless formalistic gestures.«

The City of Culture of Galicia project, near the ancient pilgrimage town of Santiago de Compostela, was won by Peter Eisenman in 1999 and is still unfinished. Designed to showcase the region’s artistic heritage, the six buildings on its 173-acre site include a library, archive, museum and theatre. (Photo: www.olympia-liechty.blogspot.de)

-

![]()

![]()

»All of this is supposed to be for the public good, there being the implicit suggestion that Spanish cities are without any intrinsic cultural value of their own until irrigated with this sort of investment.«

The stone-clad, contoured forms of the City of Culture were inspired, according to Eisenman, both by the surrounding landscape and the shape of a scallop shell, the traditional symbol of Santiago de Compostela. (Photos: openbuildings.com)

-

The disastrous City of Culture of Galicia outside Santiago de Compostela, designed by Peter Eisenman, sums up the excesses of the system with its empty rhetoric and extravagant and meaningless formalistic gestures. The folds of the project were sold to American academia through references to Deleuze (Le Pli), and to the gullible Galician locals through computerised transformations of the town plan of the old city of Compostela and allusions to the pilgrims of Santiago de Compostela. Far from being anchored in the local context, the project has decapitated Monte de Gaias and replaced it with a phony landscape with curves like those of a fun-fair roller coaster. These cynical intellectual manipulations cannot mask the reality of structures resembling supermarkets twisted about with algorithms and camouflaged with a thin veneer of granite (imported from Brasil!).

![]()

The 42.5-metre Museum of Galicia on the right is the tallest structure in the City of Culture. The hill-top site, offering views back to the the city of Santiago de Compostela, also allows the complex to be seen for miles around. To the left in the background is the Library of Galicia. (Photo: www.isabellaseveri.blogspot.de)

-

William J.R. Curtis (*1948) is an architectural historian and critic. His writings have focused on twentieth century architecture, and his best known books are Modern Architecture Since 1900 (Phaidon, first published in1982) and Le Corbusier: Ideas and Forms (Phaidon, 1986). His focus more recently has also been on re-assessing and broadening the modernist ‘canon’, and other books include Balkrishna Doshi: an Architecture for India (Mapin, Rizzoli 1989); and Teodoro Gonzalez de Leon: Obra Completa (Arquine, Reverte, Mexico 2004).

He studied at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London University and at Harvard University, and has taught and lectured extensively in Europe, USA, Australia, Asia and Latin America. Curtis currently lives in southwestern France.

This article first appeared in El Païs, Babelia, May 14, 2011

![]()

This megalomaniac scheme may well fit the Pharaonic ambitions of its original client Manuel Fraga, but it still remains half-finished, it is bankrupting the local economy in the building process, and it will cost a fortune to run. The ill-defined claims of mass cultural entertainment do not sit too well in a period of mass unemployment.

The Centro Niemeyer Asturias in Spain’s industrially depressed city of Avilés follows this general pattern of cultural marketing, given that no one seems to know what the architectural container is supposed to contain. The building is a curious assemblage of Niemeyer’s own architectural clichés – from an upturned flying saucer to supposedly “seductive feminine curves” – a signature building in the full sense of the word that comes close to self-caricature. Everything has been done to attract attention to the project, including linking it to actors such as Woody Allen and Brad Pitt. We learn that the building “has the potential to become a Spanish national icon,” transforming the sad city of Avilés into a world class centre of arts, culture and design. An example, then, of what Llàtzer Moix has called “miracle architecture”: just rub the lamp and the genie will appear!

![]()

![]()

The Centro Niemeyer Asturias consists of five main elements, including an auditorium, exhibition dome beyond, and above, the sight-seeing tower and restaurant. Th centre has closed and reopened twice since its inauguration in 2011, due to political and funding issues. (Left: Wikimedia Commons; Top: SurfAst / Wikimedia Commons)

-

Pebbles

in thE River(Photos: Hufton + Crow Photographers)

![]()

-

Spain is not the only country producing containers without content (as William Curtis puts it earlier in this issue). China is pretty good at it too. The Guangzhou Opera House, designed by Zaha Hadid and opened in 2010, is part of a big urban redevelopment scheme supposed to redefine the industrial image of China’s third largest city − also known as the “factory of the world” − as a neat place for nature and culture.

Zaha Hadid’s design shows three buildings with soft edges, creating public spaces with stairs and terraces that connect the building and the adjacent business district to the shore of the river: the architects describe their concept as “pebbles in the river.” Yet while 200 million US dollars were spent on the building’s construction, no money was put aside for a permanent orchestra to play in it. And now, two years after the opening, it looks like its walls are already crumbling here and there.... (fh)

![]()

![]()

-

Beacon

for Learning

(Photo: Iwan Baan)

![]()

-

This library complex, jutting out from a hillside above Medellín, is one of five planned libraries that comprise a city-wide cultural initiative. Designed by Giancarlo Mazzanti, it was commissioned by the Mayor Sergio Farjado as part of an ambitious series of educational, cultural, and infrastructural projects to improve the conditions and the futures of the majority of the population, who live in poverty in informal housing that makes up large parts of the city. These projects have contributed to changing Medellín, economically and socially, from what was once the most violent city on earth – due to drug wars and trafficking – to an industrial and cultural hub.

![]()

Photo: Iwan Baan

-

![]()

Video: “Dos gorras y una casa (Parque Biblioteca España).” Director/cutting: Youdid Kahveci, camera: Carlos Andrés López Tobón. This short movie was exclusively produced by students of the Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin (DFFB) for the exhibition “Culture:City” at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin (2013).

Photo: Sergio Gomez

-

The building consists of three, five-storey, slate-clad, façeted blocks, which contain a library and reading room, auditorium, and a series of social and recreational spaces. Primarily lit from skylights, the building provides an appropriately internalized environment, whilst externally a spectacular panorama of the city can be enjoyed from its terraces.

From afar, its distinctive form stands out from the poor Barrio Santo Domingo that surrounds it, acting as a symbol of progress, visible from across the city. Rather then an “icon,” designed to define the image of the city and be consumed internationally through 2D media, it acts more as a “beacon” of learning in the spirit of the libraries built by nineteenth century philanthropists such as Andrew Carnegie, a symbol of better things for the local population, both for themselves and their city: patronage in the best sense of the word. (rw)

![]()

![]()

Photo: Diana Moreno

-

![]()

![]()

The

Island

of

HappinessThe shadowy story of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi

Text by Ann Lui

-

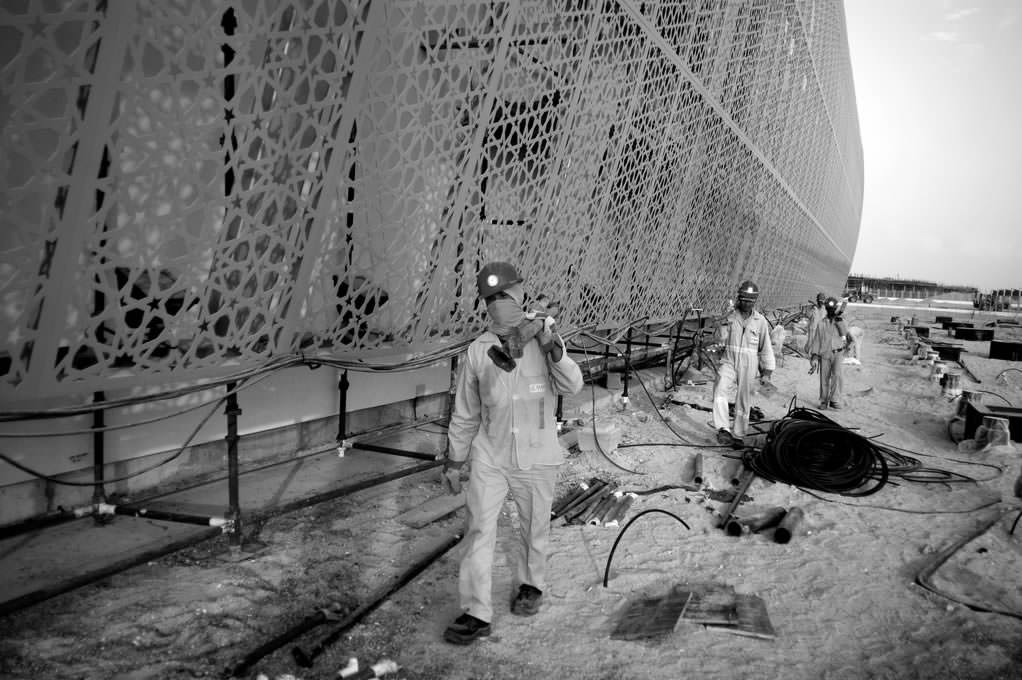

Saadiyat Island, future home of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, has generated a contentious media storm surrounding the rights of the migrant workers. Who builds these monuments to culture? Who does “culture” exploit or exclude? (Photo: © Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch, 2011)

-

![]()

![]()

The first thing you notice when reading PricewaterhouseCoopers’ report on labor conditions on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island are the strangely bright and cheerful photographs of workers. In one, two smiling men in blue jumpsuits saunter towards the camera against a blurry, bright white background. In another, a worker in sunglasses and striped scarf stands in the foreground against an array of other anonymous, uniformed men. These colorful images are juxtaposed against a much darker story.

Saadiyat Island’s Cultural District is the future site of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, designed by Frank Gehry, which will accompany a crop of cultural institutions in various states of completion around the island – the Louvre Abu Dhabi (Jean Nouvel), the Zayed Cultural Museum (Foster + Partners), the Performing Arts Center (Zaha Hadid), and the Maritime Museum (Tadao Ando) – a five-for-five roster of Pritzker Prize winners. Besides these institutions, the masterplan includes an NYU campus, hotels,

PricewaterhouseCoopers was hired to write a report on Saadiyat Island's working conditions. However, images and information in the report may obfuscate the real situation on the island. (Photo: TDIC/PwC report, 2012)

-

resorts, and a marina. When construction in these firms’ own countries slowed during the recession, they were contracted for large-scale projects in a country with a seemingly more-resistant economy.

PricewaterhouseCoopers, one of the world’s “Big Four” accountancy firms, was hired by the Tourism Development and Investment Company (TDIC) to “independently” monitor worker conditions on the developer’s ongoing Saadiyat projects. TDIC, an Abu Dhabi-based firm chaired by Emirati, commissioned these annual reports in the wake of an 80-page investigation by the Human Rights Watch (HRW) in 2009. The report detailed widespread labor violations at the future sites of these high-profile institutions.

![]()

Thus far, only the retaining walls and foundation piles of the future museum have been completed - though apparently a series of Guggenheim-run programs will already begin this spring. (Photo: © BAUER Group, 2012)

»When construction in these firms’ own countries slowed during the recession, they were contracted for large-scale projects in a country with a seemingly more-resistant economy.«

-

In a 2009 report on Saadiyat Island, Human Rights Watch reported worker exploitation including the prevention of migrant laborers returning to their home countries. (Photo © Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch, 2011)

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

An artist coaliton called GulfLabor was formed in 2010, boycotting the Guggenheim due to its alleged human rights violations against workers like these. (Photo: © Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch, 2012)

-

»Despite an artists’ strike and ever-darkening discourse on labor conditions at the museum-in-progress, its opening date hovers on the horizon, always just a few years out of reach.«

Six years after the Guggenheim project was unveiled, despite an artists’ strike and ever-darkening discourse on labor conditions at the museum-in-progress, its opening date hovers on the horizon, always just a few years out of reach. So far, all that exists of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi are concrete piles, Gehry Partners’ renderings, and PwC’s obfuscating report.

The original HRW report on Saadiyat, ironically billed as the “Island of Happiness,” chronicled the systematic and institutionalized abuse of construction workers — mostly migrant — on job sites. On the blind side of the pamphlets advertising “world class leisure,” the HRW reported exploitation of laborers from South Asian countries who, upon arriving at Saadiyat, found themselves “deeply indebted,

badly paid, and unable to stand up for their rights or even quit their jobs.” Following this report, in 2010 a group of 130 artists led by Walid Raad formed the coalition GulfLabor. The coalition, whose numbers have since multiplied, formed a boycott of the Guggenheim and called on the institution to take responsibility for its labor conditions – instigating a growing media stir. In May 2011, TDIC appointed PwC to provide a public annual report. Yet critics question whether this appointment is truly objective: PwC continues to do business with government-owned companies in the region and furnished its first report with an ample disclaimer that its work did not “constitute a review with generally accepted auditing standards.”

-

(Photo: © Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch, 2011)

-

Amid continuous discourse, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi itself is suspiciously phantomlike. Model images provided by Gehry Partners show an odd cousin of the architect’s landmark Guggenheim Bilbao. A protruding central axis is flanked by mid-rise forms of the designer’s trademark curvaceous metal panels and a seemingly random aggregate of exterior wall forms. In the fall of 2011, TDIC cut its overall yearly budget by 28 percent. The same year, bids by international contractors for the concrete works on the project were cancelled and their fees returned. Though Gehry’s multifaceted mass was scheduled to open this year, even the persistently positive director of the Guggenheim, Richard Armstrong, told The Art Newspaper: “I don’t always know everything that is going on there.” Thus far only retaining walls and foundation piles have been poured – barely the beginnings of building as immense and complex as Gehry’s proposal.

![]()

(Photo © Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch, 2011)»Architects hold little legal responsibility for workers’ rights and safety.«

-

![]()

An artist coaliton called GulfLabor was formed in 2010, boycotting the Guggenheim due to its alleged human rights violations.

(Photo: © Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch, 2011)

»The media fanfare surrounding starchitects like Franky Gehry creates both a responsibility and an opportunity beyond what is stated on a contract.«

-

![]()

Besides Gehry’s Guggenheim, Saadiyat Island is the site of the Louvre Abu Dhabi (Jean Nouvel), the Zayed Cultural Museum (Foster + Partners), the Performing Arts Center (Zaha Hadid), and the Maritime Museum (Tadao Ando) – not to mention endless resorts, hotels, and tourist fun. (Video and image courtesy TDIC)

-

Ann Lui is a designer and writer living in Boston, interested in the confluence of narrative and building. She studied architecture at Cornell University and has worked on projects across scales and disciplines from investigative 3D fabrication to urban high-rises. She studies the relationship between science fiction and architecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and is currently working at a local design firm specializing in historically-aware projects while on hiatus from school.

The heart of a museum, its art collection, is also notably missing here. The Guggenheim has promised a contemporary and regionally-focused collection of artworks, while treading lightly around discussion of censorship with its sponsors. Yet many highly-billed artists it would ostensibly include are participating in the boycott. During six years of postponements, the UAE’s local art scene has grown in its own right, including the Sharjah Biennal and Art Dubai (both approaching at the end of this March) and a burgeoning gallery network. The Qatari royal family has invested one billion pounds in contemporary art in the past seven years, according to the Guardian. Today, gallerists in Dubai say that they “don’t need” the Guggenheim, perhaps doubtful whether the western institution’s name recognition can offset the likely struggle to curate a comprehensive and critical collection. As of March 17, 2013, a list of participating artists in a new “Public Program” was released. It looks like programming will forge ahead with or without a building.

Architects hold little legal responsibility for workers’ rights and safety; after contract documents are completed, contractors take the reins. However, the media fanfare surrounding starchitects like Franky Gehry creates both a responsibility and an opportunity beyond what is stated on a contract. In other Saadiyat Island projects, such as the Beach Residences, TDIC is aiming for LEED certification. LEED, which has institutionalized metrics for the ever-nebulous goal of sustainability, includes provisions for building occupant comfort, yet barely mentions worker safety. Across the board, green projects have been no worse — but no better than — traditional projects in terms of worker safety. LEED certification through positive reinforcement has raised standards on occupant comfort alongside its more quantifiable measures. Yet the (lack of) “sustainability” of forced labor by migrant workers remains to be folded into the accreditation process.

Plans for the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi show a proposed 30,000 square feet of gallery and support space. Yet assessment of both the edifice and its art collection has been obscured by the discourse surrounding its unfinished construction. Whereas other architectural projects may be discussed in terms of their formal qualities or experiential effects, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi is formed by reports, documents, petitions and letters. When the dust clears, and this whirlwind of documents settles, beneath it we find not a building but the exploitation of thousands of migrant workers.

![]()

-

Fashion

Forward

(Images courtesy Foster + Partners)

![]()

-

2045 might seem far in the future – but for an urban development project at the scale of the West Kowloon Cultural District, it’s an ambitious goal for completion. A mere thirty years from now, West Kowloon’s master plan could be a shining example of sustainability and culture, a glittering beacon of hope for the future of western Hong Kong. Art, music, education, fun, work, and “life” will harmoniously and carbon- neutrally coexist throughout the waterfront district’s mix of iconic buildings and outdoor arenas – or at least that is what the imagery of the planners promises.

Like a good, fashion-forward wardrobe, West Kowloon’s got the perfect mix of flashy statement pieces, eco-friendly garments, understated casual items, and a touch of class – all custom designed for China’s, er, “Special Administrative Region” by Foster + Partners. It might be best to keep the receipt for this purchase, though... at 21.6 billion Hong Kong dollars, is there a return policy on that? (ew)

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

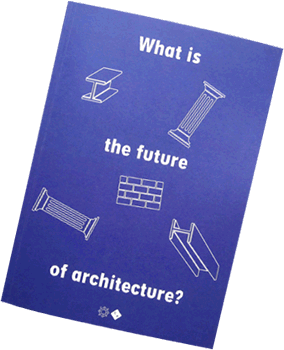

What is the Future of Architecture?

Crap is Good, 2012

Initiated and organized by Pieterjan Grandry

257 pages, 170 x 240 mm

ISBN 978-3-00-040029-2

www.the-future-of.org

www.crapisgood.com

![]()

Sometimes the most straightforward questions can beget the most remarkable answers. (Why else would interviews with Hans Ulrich Obrist be interesting?) A recent book published by Crap Is Good, called What is the Future of Architecture?, contains responses to its straightforward title question from 53 contemporary practitioners. Presented in alphabetical order, the contributions form an eclectic encyclopedia, from essays to recorded conversations to stories to drawings.

Despite the surface-level similarity of many pieces in the book – likely due to maximal usage of buzzwords like “sustainability” and “participatory design” – there are some truly strange/great bits to be found, like Bading Kagalakan’s Voilà! Architecture Manifesto: “Georges Pompidou Centre in Paris looks like a Botticelli portrait with acne. ...Voilà! Masculine bodies will be our roof water drainers!”

Yet some opinions in the book are downright oppositional, particularly regarding uncube’s current hot topic, culture. While Kyle Matthew Greene writes that “architecture is the generator of culture,” Marjetica Potrč writes that culture clearly comes first. We can only hope that, in the future, architecture will continue to be so provocative. (ew)

![]()

![]()

-

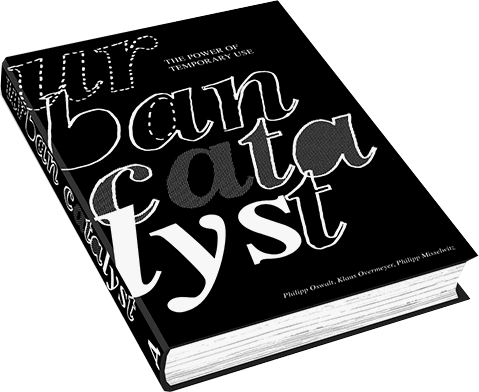

Urban Catalyst: The Power of Temporary Use

Philipp Oswalt, Klaus Overmeyer, Philipp Misselwitz

DOM Publishers, 2013

Hardcover 165 x 235 mm, 384 pages

ISBN 978-3-86922-261-5

www.dom-publishers.com

The team behind the Urban Catalyst research initiative began as iconoclastic proponents of the urban ad-hoc. With the publication of their eponymous book ten years after the start of the project, Philipp Misselwitz, Philipp Oswalt and Klaus Overmeyer cement their role as pioneering documentarians and actors in the urban informal. The book details the projects’ examination of the economies and strategies of temporary use’s power to operate in the city – and the significant change it can engender, outside of typical political/financial structures. (jb)

![]()

![]()

-

Constructing Images

In issue No. 09 we’ll take a close look at the eternal struggle of reality vs. representation, or rather: the image vs. the truth, the central tension at the heart of all art, architecture, and design. Pictures may be representations of reality, but they also construct our understanding of what reality is.

![]()

OFFICE developed this vision of “Cité de Refuge” in Ceuta, Morocco for the Architecture Biennale in Rotterdam in 2007. (Image: © OFFICE Kersten Geers David van Severen, Brussels)

![]()

![]()

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Don‘t fight forces, use them.«

Richard Buckminster Fuller

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents