-

Magazine No. 14

Small Towns, Big Architecture

-

No. 14 - Small Towns, Big Architecture

-

page 02

Cover

Small Towns, Big Architecture

-

page 03

Editorial

Small Towns, Big Architecture

-

page 04 - 08

Outsized I

Curiosities, cash cows and carbuncles...

-

page 09 - 22

Small Town, Big Modernists

Trophy architecture in the Midwest

-

page 23 - 26

Outsized II

Curiosities, cash cows and carbuncles...

-

page 27 - 37

Le Village Radieux

Le Corbusier's big city visions funnelled into a small town

-

page 38 - 42

In the Photo Booth with...

Tatiana Bilbao

-

page 43 - 46

Outsized III

Curiosities, cash cows and carbuncles...

-

page 47 - 54

The Colossus of Rügen

Prora, the gigantic Nazi-built resort on the Baltic Sea

-

page 55 - 57

Bookmarked

-

page 58

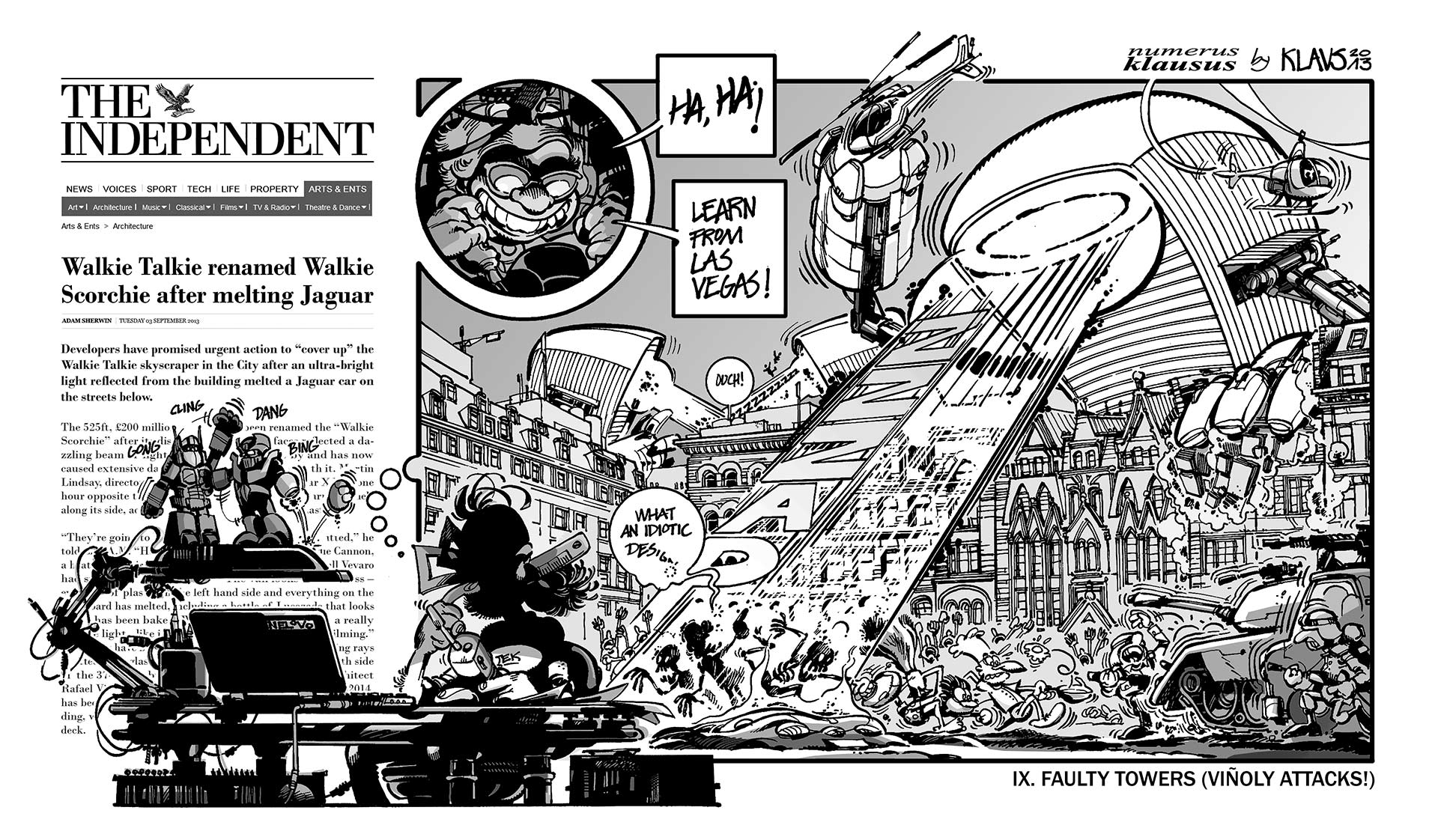

Klaustoon

IX. Faulty Towers (Viñoly Attacks!)

-

page 59

Next

Veins

-

-

uncube's editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Elvia Wilk, Florian Heilmeyer, Jessica Bridger, and Rob Wilson. Graphic design: Lena Giavanazzi.

uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online magazine covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

![]()

![]()

Everybody wants a Gehry.

How many unprepossessing small towns dream of having a piece of starchitecture to boost their local economy?

The culture of important architecture pre-dates our current celebrity obsession with big names. This issue of uncube looks at “big” buildings in their “small” contexts from an industrial philanthropist’s modernist vision in Indiana to a 4.5km-long Nazi seaside resort on the Baltic coast via a Le Corbusier chapel completed 41 years after his death.

A world tour of monuments to the ethos: “size matters”.

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Curiosities, cash cows and carbuncles...

OUTSIZED

-

The Goetheanum

![]()

Architect: Rudolf Steiner

Size: 110,000 m³

Date: 1928

Use: Centre for Anthroposophical Society

Location: Dornach, Switzerland

Population: 6,375The architecture of the Goetheanum is based on philosopher and esoteric Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophic principles, inspired by the spiritual world rather than abstract theory.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

-

![]()

(Photo courtesy De La Warr Pavilion)

![]()

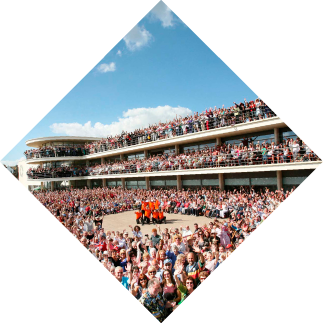

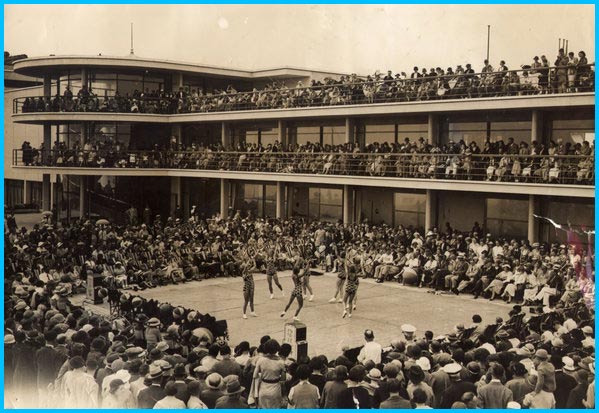

De La Warr Pavilion

![]()

Architects: Erich Mendelsohn and Serge Chermayeff

Size: 4,000 m²

Date: 1935

Use: Public Entertainment Hall

Location: Bexhill-on-Sea, UK

Population: 41,173One of the first modernist buildings in England was built in a little seaside town. The De La Warr Pavilion celebrated its 75th anniversary by recreating a photograph published by the Daily Mirror in 1936.

(Photo: Sheila Burnett)

-

Thomson Correctional Center

![]()

Architect: Unknown

Size: 58,064 m²

Date: 2001

Use: Maximum security prison

Location: Thomson, Illinois, USA

Population: 590This private maximum security prison was built for 1,600 inmates – three times the size of the local population. Although it closed in 2010, it is now the centre of a controversial debate over a proposal to rehouse Guantanamo Bay prisoners there.

(Illustration by Madalena Boavida Guerra)

-

Wat Rong Khun

![]()

Architect: Chalermchai Kositpipat

Size: Under construction

Date: 1997 - ongoing

Use: Buddhist temple

Location: Chiang Rai, Thailand

Population: 67,176The White Temple mixes elements of traditional Thai Buddhist art with contemporary imagery. The interior murals include an apocalyptic battle scene involving spaceships, Spiderman, and George W. Bush.

(Photo: Kyle Peirson)

-

(Photo courtesy Columbus Area Visitors Center)

![Small Town, Big Modernists - Trophy architecture in the Midwest - Text by Elvia Wilk]()

-

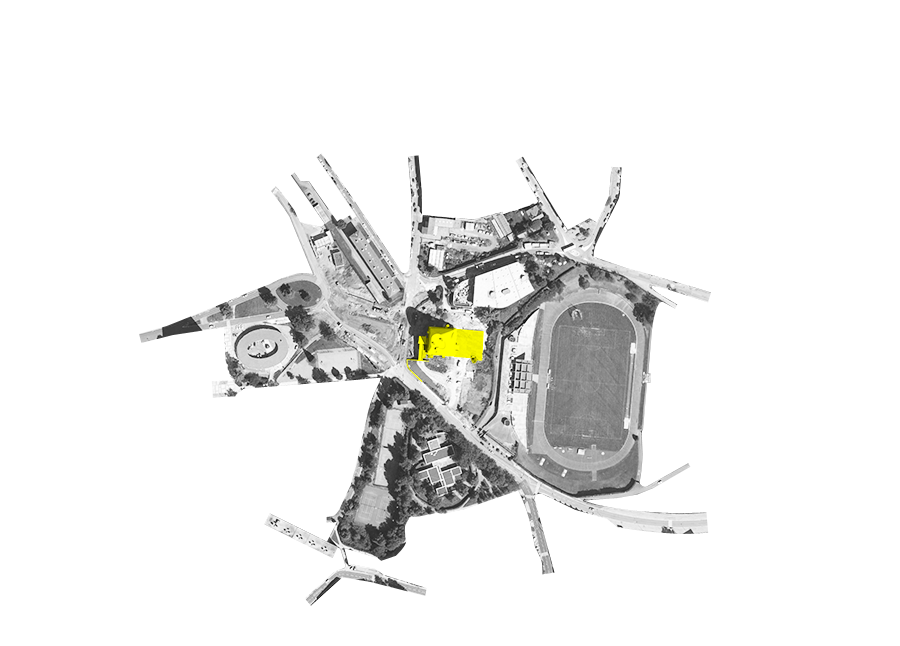

Until this year I had no idea that the so-called “sixth most important city for architecture in America” was just an hour’s drive away from my Indiana hometown. But on a long-overdue visit to Columbus, Indiana last summer, I encountered a veritable mecca for architecture devotees. Nestled within its city limits over 80 pieces of notable architecture can be found — many of them modernist masterworks by the likes of Eero Saarinen and I.M. Pei.

As much as the buildings themselves, it’s the story behind the architecture that makes Columbus so compelling a place. This is a story that reaches across generations, illuminating the ways in which the history of modern architecture in America is intertwined with the histories of industrial development, private enterprise, and public service. It’s a story firmly rooted in Midwestern culture, but it’s as much a story about Indiana as it is about the country as a whole − getting right to the heart of one fundamental question: what is the value of investing in public architecture?

![]()

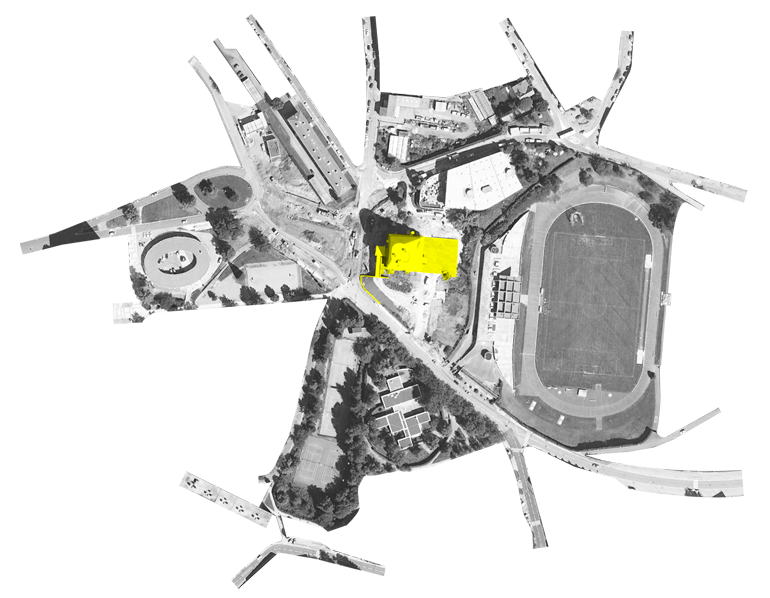

Columbus’s wealth of architecture includes six national landmarks and work by four Pritzker Prize winners: Kevin Roche, I.M. Pei, Richard Meier, Robert Venturi. (Photo courtesy Columbus Area Visitors Center)

-

Cummins Engine Company

The architectural marvel that is Columbus is the result of innovative and unique political, entrepreneurial, philanthropic, and civic experimentation on a city-wide scale. The man behind the experiment was J. Irwin Miller, and Columbus was his petri dish.

Miller was born in Columbus in 1910. After studying at Yale and Oxford he returned home in his twenties to take over management of his great uncle’s business, the Cummins Engine Company. In the 1930s at the height of the Great Depression, Cummins was an ailing enterprise – yet under Miller’s savvy management as the national economy began to recover, the company finally began to profit.

Cummins expanded throughout World War Two thanks to the war industry’s demand for diesel engines, and it continued to grow as the construction of the nation’s first interstate highway system stimulated a postwar manufacturing boom. Today, Columbus is still an industrial hub — a vital 37 percent of employment is in the manufacturing sector, much of it automotive, and much of it powered by the company now called Cummins Incorporated. Miller was undoubtedly the business genius behind the success of the company that has defined the city for the last century — and in turn he became a defining figure.

![]()

J.Irwin Miller inspecting a diesel engine at Cummins circa 1950. (Photo © 2012 Indiana Historical Society)

-

![]()

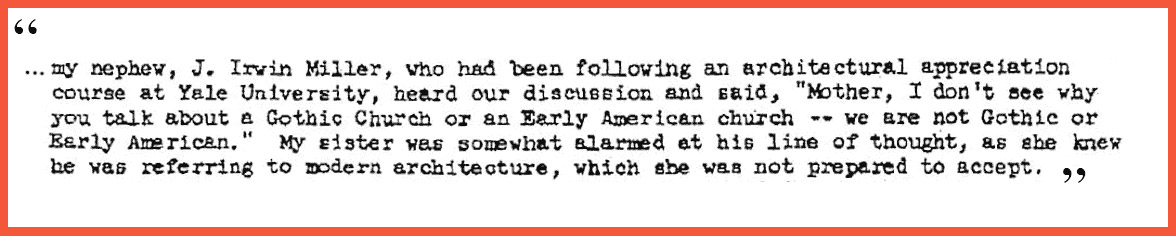

From a letter by Elsie Sweeney, Miller’s aunt, that tells the story of how their family convinced both the community and the architect to build a modernist church.

THE ECUMENICAL MODERNIST

Fueled by its thriving industry, Columbus almost doubled in size between 1920 and 1950, ballooning to a population of around 18,000. The baby boom demanded new public infrastructure, and fast — schools and churches were quickly becoming overcrowded.

Miller was an avid Christian. In his twenties, he also became an avid devotee of modern architecture. When the congregation of his family church outgrew its cramped building in the early 1930s, he seized on the opportunity to join his passions and hire a practicing modern architect to come to Columbus to design a new church.

Miller believed in the importance of contemporary architecture at a time when traditional styles, particularly for religious buildings, still reigned in the USA. Convincing the church congregation to build a modernist church wasn’t easy — but persuading the architect turned out to be just as hard. Miller’s top choice was Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen, who was based in nearby Detroit. Unfortunately Saarinen was no fan of American religiosity, and he was explicitly against the idea of building an American church. “They are too theatrical – they are not my idea of religion,” he reportedly told Miller’s mother.

Miller’s entire extended family became enthusiastic proponents of the plan, and over time the Miller-Irwin-Sweeneys managed to persuade Saarinen. They argued that modernist architecture was needed precisely because it reflected their specific religious values. Informed by the Ecumenical movement, which promotes interdenominational unity, theirs was a particularly Midwestern brand of religiosity: moderate, modest, and inclusive. Miller’s mother explained: “While we should like the church to be beautiful, we do not want the first reaction to be, how much did it cost?”

-

![]()

First Christian Church was built by Eliel Saarinen in 1942 and was the first modern building in Columbus. It has a simple, geometric form, with a buff brick and limestone façade and a 166-foot high free-standing belltower. (Photo courtesy opus408d.blogspot.de)

-

![]()

Southside Elementary School, built by Eliot Noyes in 1969, is a stunning Brutalist structure of precast concrete. Despite its stature, parents have been known to question its appropriateness – isn’t elementary school brutal enough?

The Cummins Foundation

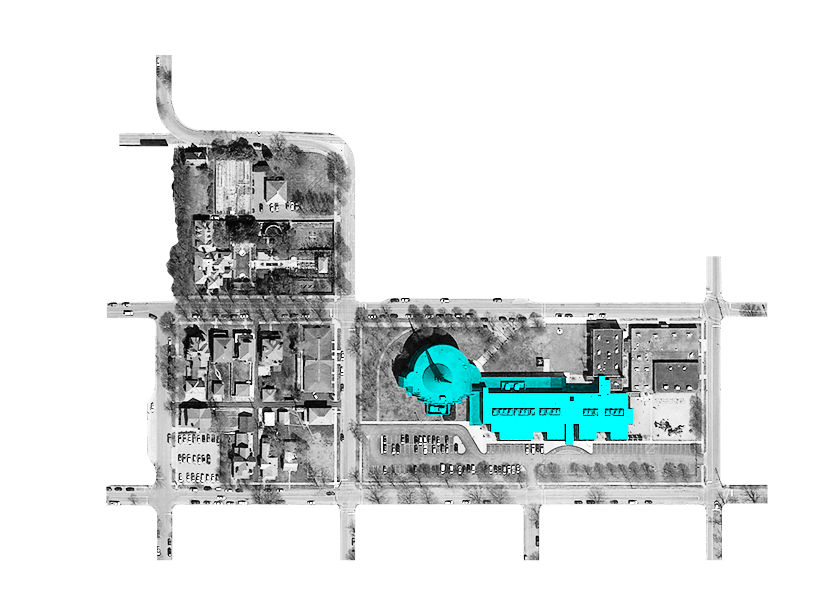

In the 1950s, the Bartholomew County Public School Board of Columbus realized a new elementary school would have to be built every two years to keep up with increasing citywide birth rates. Two pre-fabricated school buildings were hastily erected. Upon observing the shoddy quality of the structures, Miller decided to stage another architectural intervention.

In 1954 he founded the Cummins Foundation for public architecture, financed by profits from his thriving corporation. He approached the school board with a proposal: he would draw up a list of five possible architects to build the next school, and if the board could agree on one, the foundation would pay the architect’s fees and ten percent of the construction costs. Harry Weese was invited to take on the first project, designing the Lillian C. Schmitt Elementary School in 1957.

Miller’s proposal met with resounding success, and under its aegis four schools were built in five years. He soon decided to expand the program’s reach, and over the coming half century it would facilitate the construction of everything from fire stations and hospitals to golf courses and public housing. In each situation, the choice of architect was left to the governing body of the institution. They ended up selecting many of the architects who would come to shape modernist architecture in the USA, partially through their work in Columbus.

The participative aspect of this process was a crucial facet of Miller’s philosophy. He wanted local organizations to have a say in developing the landscape of their city, and he wanted the architects to be welcomed rather than met with skepticism. This allowed for experimentation that might not have been able to take place elsewhere; with community support, unique projects were made possible.

-

![]()

Robert Venturi completed Fire Station No. 4 in 1967, fulfilling the fire department’s request for a fully-functioning station on a tiny 200 by 125-foot site via a trapezoidal floorplan with few interior right angles. (Photo: courtesy Columbus Area Visitors Center)

![]()

Irwin Office building, formerly the Irwin Union Bank, was a collaboration between Eero Saarinen and landscape architect Dan Kiley in 1954. It was one of the first banks in the USA to abandon neoclassical style in favor of open space and glass. (Photo: courtesy Columbus Area Visitors Center)

![]()

Lillian C. Schmitt Elementary School was built in 1957 as Cummins Foundation’s first project. (Photo: Harry Ueese)

-

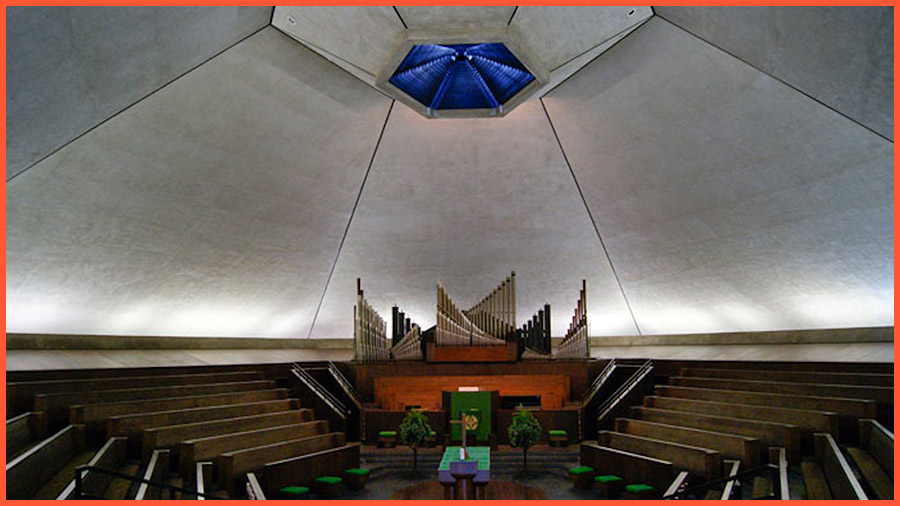

Cummins did not finance churches or private businesses, but as Columbus gained an identity as an architecture destination, local citizens began to invest their personal resources in high-quality architecture. Eero Saarinen’s North Christian Church, completed in 1964, was one such building financed by private means. (Photo: courtesy Columbus Area Visitors Center)

![]()

-

Miller House & Garden

When Eliel Saarinen arrived in Columbus in the 1940s to break ground for First Christian Church, he brought along his son Eero and Eero’s friend Charles Eames. Miller became fast friends with Eames and the younger Saarinen and thus began a lifelong friendship and working relationship.

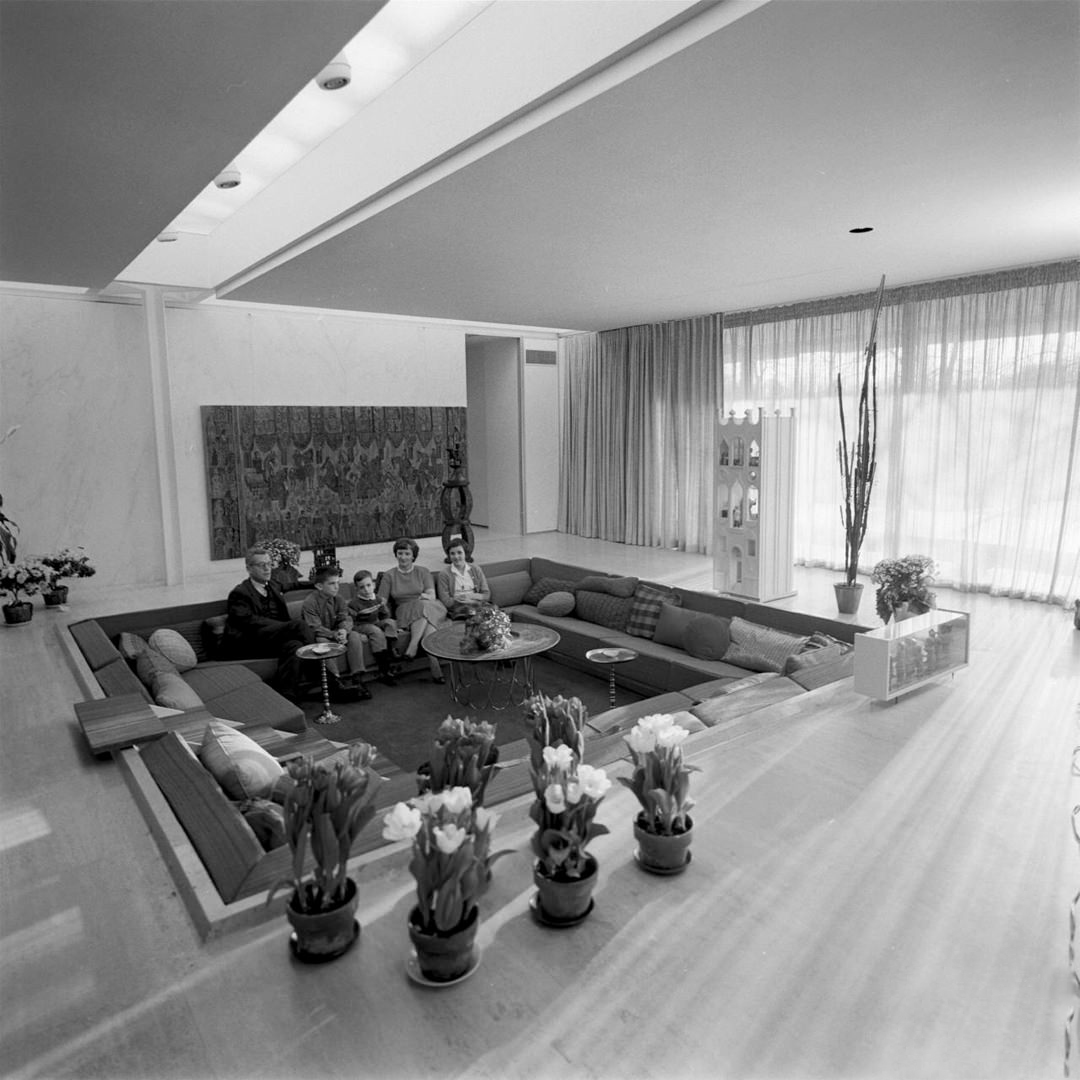

In 1953, Miller bought a 13.5-acre plot of land on the northwestern edge of Columbus and asked Eero Saarinen to design his family’s home there. Over the next four years Saarinen, along with interior designer Alexander Girard and landscape architect Daniel Kiley, worked to create what would become one of a handful of iconic glass houses signaling the advent of modernism in America, alongside Philip Johnson’s Glass House (1949), Charles and Ray Eames’ Pacific Palisades House (1949), Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House (1951), and Eliot Noyes’ house in New Canaan (1954).

![]()

With its low-slung roof, walls of stone and glass, and cruciform steel columns, the Miller House epitomizes the modernist dwelling of its time. (Photo: Leslie Williamson, courtesy Dwell)

-

![]()

The Miller family were photographed in their home for LIFE magazine in 1961. Today the home is preserved as a museum and open to the public. (Photo: Frank Scherschel)

![]()

As opposed to most of its contemporary glass-walled houses, the Miller House was made to be lived in. Saarinen’s “Conversation Pit” was one of several features designed for the seven-person Miller family. (Photo courtesy IndyStar)

-

“This man ought to be president”

Miller intended for his architecture initiative to attract people to Columbus. This hope was partially driven by a personal desire to have interesting people around him — he wanted to engage in conversation with the thinkers of his day. But it was also in his personal financial interest to make the city appealing for new citizens. As Columbus became known for its rich local culture, it became more attractive for job seekers; in other words, as quality of life went up in Columbus, so did Cummins’ employee pool. Furthermore, his investment fed back into the long--term city economy via tourism, which today accounts for over USD 300 million of annual revenue.

Herein lay the crux of Miller’s experiment. With the Columbus model Miller demonstrated how investing in culture can feed back into private business, creating a symbiotic relationship between social and economic growth. He practiced philanthropy with a business incentive, proving that fostering public well-being can directly contribute to private gain. As a partisan debate about whether it is more profitable to invest in business or culture continues to divide the country today, Columbus remains relevant and powerful evidence that the two can be mutually supportive.

![]()

Besides his contributions to public life through architecture, Miller also used his business success as leverage for civil rights causes. On the local scale, he unionized the labor force at his own factories; on the national scale, he helped organize the civil rights March on Washington; globally, he declined to invest in South Africa as a protest against Apartheid. In 1967, Miller's profile graced the cover of Esquire with this superlative subtitle. (Image © Indiana Historical Society)

-

Impressively unspectacular

As I walked the streets of downtown Columbus on a weekday afternoon last summer, a tourist map in one hand and a camera in the other, I scrutinized the city for signs of that special aura that our current era of starchitecture has taught us to expect. There were plenty of formally-impressive structures to be found — the cuboid volume and colossal tower of First Christian Church; the dramatic brick arms of City Hall; the massive dome crowning the Bartholomew County Jail — but overall I was struck by the pleasant ordinariness of it all.

Kids were leaving summer sports practice from Gunnar Birkerts’ stunning monolithic school. The sunlit brick interior of the I.M. Pei library was bustling with teenagers gossiping over their books.

![]()

(top) Students at Lincoln Signature Academy play sports, eat lunch, and attend lectures every day in this multi-purpose space designed by Gunnar Birkerts in 1967. (Photo courtesy Columbus Area Visitors Center)

(right) Cleo Rogers Memorial Library was built in 1969 by I.M. Pei, who was chosen over contenders Phillip Johnson and Irving Stone for his plan based on the form of a public plaza. (Photo: Elvia Wilk)

-

It’s not that fantastic architecture is taken for granted in Columbus. It’s that, over decades, the architecture initiated by Miller has been fully integrated into the fabric of everyday life. The buildings may serve a secondary function as archi-tourist attractions, but unlike much pilgrimage-worthy architecture, they serve primarily as inhabited, functional public spaces. Miller’s greatest achievement was not to persuade the giants of modernism to descend on a sleepy midwestern town. It was to make well-designed architecture ubiquitous and accessible enough to seem entirely warranted in a normal place. It was, overall, to make great architecture seem entirely....ordinary. I

The steeple of Birkert’s St. Peter’s Lutheran Church (1988) rises up over football goal posts and street signs in the heart of the city. The cityscape of Columbus is perpetually evolving, still due in large part to the Cummins Foundation, which continues to support an average of one new piece of architecture a year since 2000. (Photo: Elvia Wilk)

-

Great Mosque of Djenne

![]()

Patron: Sultan Kunburu

Size: 5,625 m²

Date: 1180 – 1330, rebuilt 1907

Use: Mosque

Location: Djenne, Mali

Population: 32,944The world’s largest adobe structure has been maintained for centuries by local communities who participate in an annual restoration festival during which local organic materials are reapplied to the building’s surfaces.

(Photo: WikiCommons © Gilles Mairet)

-

![]()

Facade mapping display on the Aalto building to celebrate the 75th anniversary of Wolfsburg, June 2013. (Video courtesy of intolight and ruestungsschmie.de)

Alvar Aalto Kulturhaus

![]()

Architect: Alvar Aalto

Size: 1200 m²

Date: 1962

Use: Cultural centre

Location: Wolfsburg, Germany

Population: 120,889Wolfsburg was originally founded in 1938 to house 1,000 workers for Volkswagen Beetle production. The town grew, but is dwarfed to this day by the huge VW production buildings, brand pavilions and cultural constructions such as Zaha Hadid’s Phaeno Science Centre.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

-

Kastello Mansions

![]()

Architect: Self-built

Size: 1000 m²

Date: Mid 1990s - ongoing

Use: Private residences

Location: Iasi, Romania

Population: 290,422“Kastellos” (castles) is the name given to the bombastic mansion style of wealthy Roma citizens in Romania. Characterised by layered roofs and sculptural metalwork, they are designed to reflect the financial and social clout of the owners.

(Photo: Carlo Gianferro)

-

Vitra Campus

![]()

Architects: Herzog & de Meuron, SANAA, Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry, et al.

Size: 240,000 m²

date: 1953 – 2013

Use: Corporate campus

Location: Weil am Rhein, Germany

Population: 30,011An ongoing project built over half a century by a German furniture manufacturer to house their factory, museum and showrooms, this campus concentrates a remarkable collection of starchitecture in a small town on the Swiss border.

(Photo: Julien Lanoo © Vitra, vitra.com)

-

![]()

Le

Village

RadieuxLe Corbusier’s big city visions funnelled into a small town

Text by Anneke Bokern

-

![]()

A mountain of modernism: the concrete cone of the church of Saint-Pierre provides a back-drop to a Firminy street, one that is almost on the scale of the nearby hills. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

The square in front of the little train station of Firminy is incredibly neat. Coming from the nearby industrial moloch of St Etienne, you feel like you’ve landed on a different planet. The gravel is freshly raked, the lawn almost artificially green. A shopping street leads into an unremarkable town centre, with a market square, city hall, neo-gothic church and some typical French corner bars. Nothing could be more ordinary. Until you turn up a small street lined by old workers’ houses and suddenly a huge concrete cone looms at its end. Silent and monolithic, it sits like a fossilized spaceship. Yet despite its archaic appearance, it’s the one of the youngest buildings in town.

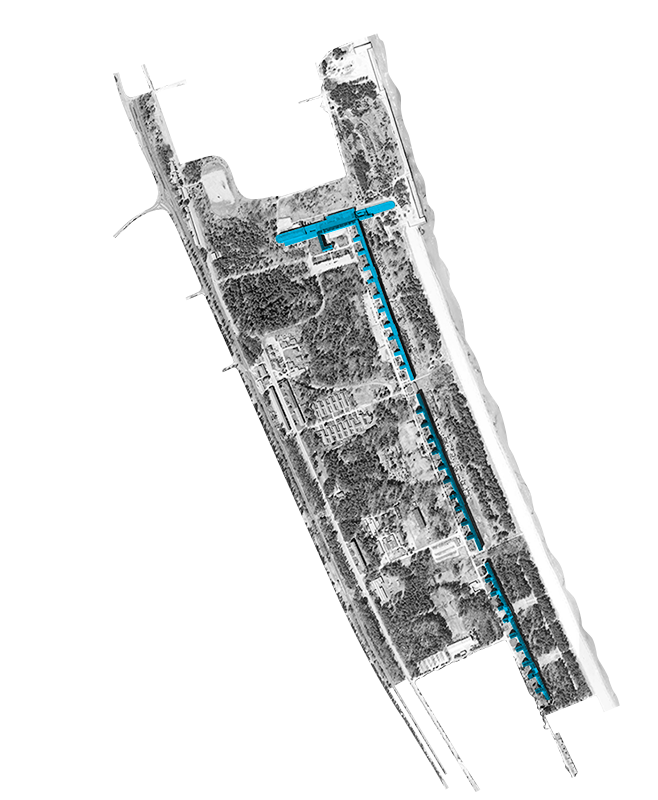

The concrete cone is the church of Saint-Pierre, designed by Le Corbusier around 1961, but finished posthumously in 2006. It’s actually the fourth building by the architect in Firminy, giving this one-horse town in central France, with its 17,000 inhabitants, the highest per-capita concentration of Corbu-buildings in Europe. In fact, you’d have to travel as far as Chandigarh to find more of his works in one place. As well as the church, there’s a Corbu Unité d’Habitation, stadium and cultural centre. The huge Unité is enthroned on a hill behind the town, but the other buildings look as though they have rolled together into the hollow below like marbles. Together with a swimming pool and a gymnasium, designed by Corbu’s student André Wogenscky, they were all planned as the social centre of Firminy Vert, the modernist city extension, awarded the Grand Prix d’urbanisme in 1961.

»Silent and monolithic, it sits like a fossilized spaceship«

-

»We have to build the city in the sun, in the light, surrounded by nature, that’s what determines our urbanism«

City in the Sun

Firminy Vert was first proposed by Firminy’s then mayor Eugène Claudius-Petit, formerly the French minister for reconstruction and urbanism. At that time Firminy must have been a pretty grim place. A dirty, black mining town, stuck knee-deep in the 19th century. The population, which had expanded from 2,600 inhabitants in 1820 to over 20,000 in 1937, was still living in conditions similar to the early days of the industrial revolution, whilst coal mining and iron smelting remained its main industries.

So Claudius-Petit decided to build a new worker’s housing area, naming it Firminy Vert – “green Firminy”, as opposed to the existing sooty “Firminy la Noire” or “Firminy the black”.“We have to build the city in the sun... in the light... surrounded by nature”, he proclaimed, “that’s what determines our urbanism. We have to build it with dignity, that’s what determines our architecture. We have to build it with simplicity, because we’re poor.”

If Claudius-Petit had had his way, Firminy would have become even more of a Corbu “Valhalla”. At the start he wanted his architect friend to design Firminy-Vert’s masterplan as well as its buildings. But after the inhabitants of Firminy heard stories about Le Corbusier’s megalomanic plans for a ville radieuse, he was only asked to design the centre civique, while a no-name colleague was given the commission for the urban plan. Nevertheless, it remains very Corbusian: 4-storey apartment blocks floating in green space, interspersed with high-rise slabs and tower blocks; its architecture is modernist in a rational, serialised and unobtrusive way.

-

Central “Firminy Vert,” originally slated to be completely planned by Le Corbusier, showing the numerous modernist high-rise residential towers around the Church of Saint Pierre. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

-

![]()

![]()

Later, in 1965, Le Corbusier was also commissioned to design three Unités for Firminy Vert, but only one was realized. It has suffered a mixed fate: a modernist latecomer, it wasn’t popular and a third of it was closed up in the late seventies, due to a lack of tenants for the apartments. Twenty years later, however, the entire building was reopened - with the exception of the top floor school, which remains a sealed time capsule.

![]()

One Unité d’Habitation was completed in Firminy (three were planned). This housing block contains around 500 apartments and originally had a school at the top for the residents’ children. Since its closure, its mothballed interiors are still full of the original furniture and features, like low-level windows in the school designed for the young pupils. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

-

![]()

![]()

The church of Saint Pierre is otherworldly inside and out, whether in the day or at dusk. These photographs show the building just after completion in 2006. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

Abandoned science-fiction movie set

Entering the centre civique is like walking onto the set of a science fiction movie. The hovering concrete volume of the cultural centre, the flying roof of the stadium, the insectlike gymnasium, and the church stand out. Finished by Le Corbusier’s former student José Oubrerie, Saint Pierre is an anachronism: simultaneously new, ageless and dated. It has a breathtakingly beautiful interior, due to Le Corbusier’s extraordinary arrangement of windows and use of coloured glass. The space has a sacred but not specifically Christian feel. Barring the pews and altar, this could be the pagan temple of an extraterrestrial civilization.

Unsurprising perhaps: Le Corbusier was not a particularly fervent Christian himself and only agreed to design the church because it was “for workers and their families.” The bishop of Saint-Étienne disliked his design however, and withdrew the commission. After the architect’s death, construction was started anyway, financed by a private foundation, but they had only progressed as far as the plinth when the contractor went broke. The stump of the church, listed as a monument in 1995, was finally finished in 2006 – for rather profane reasons: Firminy hoped to attract more tourists and EU subsidies by completing the Corbu-ensemble, its only local sightseeing attraction. The church has never seen a single service, acting purely as a cultural venue.

-

The interior of the Catholic church of Saint-Pierre de Firminy, with pinpoints of light coming through the small round window apertures, designed by Le Corbusier to represent the constellation of stars in Orion. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

»this could be the pagan temple of an extra terrestrial civilization«

-

Fragments of a “Brave New World” (from left to right): Le Corbusier’s Youth and Cultural Center, a local school, and the roof terrace of the Unité d’Habitation, also by Le Corbusier, with the concrete sandpit of the former school’s playground. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

The dome-like form of the church of Saint-Pierre and the stadium with its flying roof , both designed by Le Corbusier, are two of the monumental buildings that form the civic centre of Firminy Vert, set against the surrounding countryside. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

-

Anneke Bokern is an architecture, design and art journalist, based in the Netherlands where she has been living since 2000. She writes regularly for German and international publications such as Bauwelt, Baumeister, DAMn°, MARK, Azure, Die Welt, Neue Zürcher Zeitung. With her company architour, she organizes architectural guided tours in the Netherlands. She has also contributed to various books and is the author of a Marco Polo guide to Amsterdam.

![]()

In Firminy, as in any village or small town in France, men gather to play boules. Less typical is the mammoth modernist public housing block looming behind. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

Le village radieux

Today Firminy Vert still isn’t a wealthy place statistically. Of the town’s 1,800 apartments, 1,400 are council-owned. More than 60 percent of the welfare recipients of Firminy live there, and nearly 30 percent of its adult inhabitants don’t have a high-school diploma. Unexpectedly, however, Firminy Vert is just as surreally tidy as the railway station’s square. The buildings are freshly renovated, there’s no litter on the grass, no tagging on the walls, no urine-stench in the corners. Women push prams under chestnut trees. Men play boule in front of the giant housing slabs. Families’ laundry hangs drying in a communal square behind brise soleil. This place actually seems to work.

So is this the modernist dream come true? Or is there a hitch? It all looks so perfect one suspects something must be wrong; a dark secret hidden under the perfect turf. The reason however may be simpler. Firminy-Vert isn’t a satellite of a big city, but an extension of a small town where everything is within walking distance. Maybe the modernists’ city planning ideas were better suited for towns the size of Firminy than Paris or Moscow. Le village radieux? I doubt Le Corbusier would have liked this conclusion. p

-

In the Photo Booth with ...

Tatiana Bilbao

There’s a new generation of talented architects in Mexico. The likes of Derek Dellekamp, Michel Rojkind, Tatiana Bilbao and Fernando Romero are all in their early 40s, all busy with projects of all sizes and all garnering international attention. So when Tatiana Bilbao came to Berlin recently to exhibit her work at Ulrich Müller’s Architekturgalerie, we jumped at the chance to arrange a meeting in our photo booth.

Interview by Florian Heilmeyer

![]()

-

You studied architecture and founded your office in Mexico City in 2004, but you also seem to have a special connection to Berlin. How come?

For a long time I had very close friends living here. I was born in Mexico City, so that is the city I love, but Berlin comes very, very close. Then in 2012 I was awarded the Berlin Art Prize by the Akademie der Künste. I don’t know why they chose me, maybe Berlin has a special connection to me as well? (laughs) I was invited to give a lecture and afterwards Ulrich Müller approached me asking if I would like to exhibit my work at his gallery. So here I am again!

-

Your early projects are dynamic, fluid forms in fair-faced concrete and remind me a bit of Hadid, yet your more recent projects have much simpler geometries and more basic volumes made of different materials. What changed?

Back when I was studying we were taught that the world is fully globalized and that we can use every material and create any form we like, anywhere in the world, which is simply not true. The quality of architecture relies heavily on the people who build it and what techniques and materials they are used to. In Mexico, like many places around the world, people working on construction sites often have little or no training and a lot of them are illiterate. To explain what you want to do and how it could be done is a big effort. So I realized that I wanted to make the construction process the starting point for my architecture – by examining the local context very closely first. I guess that’s why you’ve noticed a change in the forms of our buildings. It is indeed the result of two different approaches.

-

So is this why you called the exhibition “Under Construction” and only show pictures from the construction processes of your buildings?

I’d say my design strategies are rather archaic and simple. I have always worked with my hands, building models and drawing sketches. At my office we only use computers when the design process is almost finished. On a Mexican construction site it is the same: we don’t have the latest technologies, no high-tech machines or materials – it is still a very hands-on process. It was extremely important to me to make these processes visible in an exhibition about my work. We are aiming to make good architecture that is buildable within these conditions. If you want to understand our architecture, you have to know how buildings are built in Mexico.

-

Tatiana Bilbao was born in Mexico City in 1972. She graduated in Architecture and Urbanism at the Universidad Iberoamericana in 1996. In 1998 she was given an honorable mention for her work and also for the best thesis of the year. She was an advisor for Urban Projects at the Urban Housing and Development Department of Mexico City in from 1998-99.

Bilbao was a partner at LCM S.C. before starting her own office S.C. in 2004. That same year, she founded MXDF, an urban research centre for the production of space, its occupation, its defence and control in Mexico City, together with architects Derek Dellekamp, Arturo Ortiz and Michel Rojkind. But since all the architects involved are so busy with their own offices these days, Bilbao says, the research centre is “sleeping”.

“Under Construction” is on show in Berlin until 19 Oct 2013:

www.architekturgalerieberlin.de

Does this necessarily lead to a less complex architecture?

No, but to a less complicated process because the architecture is much better connected to the local building traditions that the local workers know well. In many cases, researching the local conditions also provides us with the main materials for the building too, be that wood, brick, steel, concrete or rammed earth. Our architecture has become much more versatile.

The building process in Mexico might not be very professional and high-tech, but it is very flexible and open. Once you understand these processes, you can take advantage of them. I

-

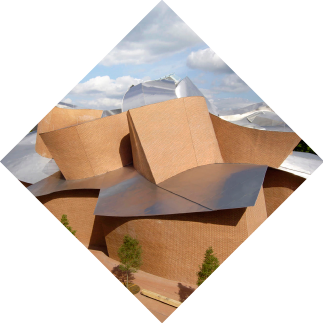

MARTa Herford

![]()

Architect: Frank Gehry

Size: 8,100 m²

Date: 2001-2005

Use: Museum

Location: Herford, Germany

Population: 65,113The little manufacturing town of Herford was clearly aiming to put itself on the architectural map when they commissioned Gehry’s “dancing sculpture” of a building for their new contemporary art museum during the economic boom at the turn of the century.

(Photo: Thomas Mayer, courtesy of MARTa Herford)

-

(Photo: Andrew Moore

andrewlmoore.com )Sutyagin House

![]()

Owner/Builder: Nikolai Petrovich Sutyagin

Date: 1992 – 2007

Use: Family residence

Size: 44m high

Location: Arkhangelsk, Russia

Population: 348,783Known as the “wooden skyscraper”, this 13-storey statement was self-built by a local Russian lumber mogul. He worked on it for 15 years before a spell in prison drew a halt to construction. In his absence his house was condemned as fire hazard — and lo and behold, it burnt to the ground in 2012.

-

Steilneset Memorial

![]()

Architect: Peter Zumthor

Size: 125m long

Date: 2011

Use: Memorial

Location: Vardo, Norway

Population: 2,122Situated in a small fishing town on the northernmost tip of Norway, this memorial commemorates victims of witch burnings in the 17th century. It houses an installation by the artist Louise Bourgeois: a flaming steel chair surrounded by a circle of mirrors.

(Photo: Bjarne Riesto)

-

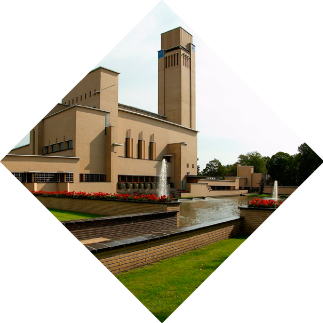

Hilversum Town Hall

![]()

Architect: Willem Marinus Dudok

Size: Approx. 8,265 m²

Date: 1931

Use: Local government building

Location: Hilversum, The Netherlands

Population: 86,030Dudok was the city architect for the town of Hilversum from 1927-54. Several public buildings, 75 houses and entire neighbourhoods bear the hallmarks of his distinctive style: flat roofs, masses and voids, strong lines and asymmetry.

(Photo: Wouter Hagens)

-

Prora, the gigantic Nazi-built resort on the Baltic Sea

Text by Jessica Bridger

THE

COLOSSUS

OF RÜGEN

-

![]()

Prora stretches 4.5 kilometres along the Baltic Sea, a crumbling remnant of Nazi-era architecture and decades of indecision and neglect. (Photo: Martjin van Exel)

Nobody loves Prora. This massive holiday venue built by the Nazis, sprawling 4.5 kilometers along the Baltic Sea, has been as hard to re-purpose as it has been to snuff out right wing German nationalism. The complex could be almost anything to anyone, but somehow Prora is largely nothing to no one.

The uneasy history of the Prora complex clouds the past, present and future of this intended resort. Prora is located in the municipality of Binz on the island of Rügen, just off the coast of northern Germany. Composed of eight interconnected structures, it is sometimes referred to as The Colossus of Rügen. Its design was largely the work of architect Clemens Klotz, and it received a Grand Prix at the 1937 World Exhibition in Paris. The aesthetic and scale, along with the idealistic goals were the brainchild of Nazi Germany’s peculiar democratic aims.

![]()

The gigantic complex has been occupied by a motley crew of users. A sample interior of a room as fitted out during useage by the East German Government shows a rather modest set up for holiday goers.(Photo: Thorsten Schramm)

-

The Portuguese artist and filmmaker Nuno Cera has been preoccupied with addressing urban conditions with his films and photography since he graduated from the Maumaus School of Art and Photography in Lisbon in 1997. His 2003 work Cimêncio with the architect Diogo Lopes, for example, is about the suburban landscape and condition, and Futureland (2008-2010) is a huge artistic investigation of nine megacities across the world. His 2005 film Prora is one in which this decaying, historically-loaded building takes a starring role and conveys the melancholy vastness of the place.

![]()

Peeling paint in a corridor of Prora is merely one view of decay. This video by artist Nuno Cera portrays Prora in a poetic state of failing. (Photo and video: Nuno Cera)

-

Planned as a vacation venue for “the masses”, the project was managed by the National Socialist organization “Kraft durch Freude” (KdF/“Strength through Joy”). The scale of the project was supposed to accommodate 20,000 visitors at a time, providing year-round, comprehensive, two-week holiday packages for German citizens.

Today the hulking behemoth is largely in ruins. Its designation as a historically-important structure has saved it from a demolition that many might favour, given its problematic provenance and subsequent uses. Constructed between 1936-39, the complex was never entirely finished as the realities of World War Two intervened, and was therefore never used as intended. It functioned as a barracks, training ground and hospital for Nazi Germany and then later the Soviet armed forces and the German Democratic Republic’s Nationale Volksarmee (“National People’s Army”), who undertook military exercises with explosive munitions that partially destroyed some of the Prora complex’s buildings. Thereafter, the steady slide into decline continued apace: after all, what can really be done with a gigantic piece of architecture in a small town? Can a giant piece of architecture be "too big to fail"?

![]()

The seaside location of Prora has done little to draw interest over the years, though the nearby town of Binz draws well-heeled tourists to the Baltic: the potential is high, but reality proves instructive. (Photo: Flickr / loop_oh)

-

The Colossus of Prora currently houses a modestly-sized youth hostel with some 400 beds, a disco and two museums: one for the history of the building and one for motorcycles. The hostel is probably the closest the complex has come to the original idealistic vision of a vacation place for (a certain kind of) everyone. Investors have come and gone, economic conditions have fluctuated since German Reunification, and most of Prora still sits decaying. A revolving cast of figures have dreamt big about Prora’s potential to no avail. It somehow ends up dwarfing them all.

Together, the location, difficult history, sheer scale and a lack of cohesive vision have combined to keep Prora derelict and deteriorating. It suffers a fate similar to other large-scale Nazi era structures (when world domination is on the menu, thinking big tends to be de rigueur) such as Berlin’s former Tempelhof Airport. Tempelhof however has the benefit of being located directly in Germany's capital city, and though decisions about its reuse have been slow, temporary programs and ambitious development ideas prove that perhaps big architecture fares better in big cities, not small ones.

![]()

Today Prora draws museum and hostel visitors - and many who simply come to gawk at the ruins of a complex designed for occupancy by 20,000 people. (Photo: Flickr / Marc)

-

With all of Prora’s challenges under consideration, two real estate development concerns, Irisgerd and Prora Haus Wismar, are in the process of trying to pre-sell luxury condominiums in former sections of the Prora complex. As of October 2013 these projects are still largely at the “investment opportunity stage”, though renovations have begun to restore the façades in the sections that will become airy residences, priced at up to 700,000 Euros. From luxury condos to a youth hostel, there is no clear trajectory for the development of Prora, only section-by-section interpretations of a mixed future.

![]()

The Seesinfonie condos at Prora – and restored façade - in rendered splendor. (Images courtesy Prora Haus Wismar)

![]()

-

The fate of Prora still hangs in the balance, vacillating between museum, hostel, luxury dream, and ruin. Memory, democracy and money have all had ample room to operate within Prora, the Colossus of Rügen, although it seems that time favours decay. I

(Photo: Flickr / Marc)

-

Occasional Work and Seven Walks from the Office for Soft Architecture

Lisa Robertson

English

Coach House Books; Third Edition

2011Hardcover 1,6 x 11,3 x 16,7 cm, 237 pages

ISBN 978-1552452325

![]()

How to describe a book about architecture which isn’t really about architecture at all? In this slim volume poet and essayist Lisa Robertson writes beautifully, leading the reader along a trail through metropolitan life in (mostly) the city of Vancouver. Now in its third edition, this collection of Robertson’s written work for various magazines, artists’ catalogs and institutions takes the lives – the human “soft architecture” of the city – in combination with surfaces, histories and geographies. From the history of the European blackberry plant to an indexing of public fountains, Robertson waxes lyrical on the vulnerable human part of the urban condition, whether venal, baroque, subtle or beautiful. This book is a treat, a way to escape into the ether of the stuff of place. (jb)

![]()

occasional work and seven walks from the office for soft architecture

![]()

-

Solution Series

Series edited by Ingo Niermann

2008 - ongoingSolution 247–261: Love. Edited by Ingo Niermann

Solution 239–246: Finland: The Welfare Game. By Martti Kalliala with Jenna Sutela and Tuomas Toivonen

Solution 214–238: The Book of Japans. By Momus

Solution 196–213: United States of Palestine-Israel. Edited by Joshua Simon

Solution 186–195: Dubai Democracy. By Ingo Niermann

Solution 168–185: America. By Tirdad Zolghadr

Solution 1–10: Umbauland. By Ingo Niermann

Solution 11–167: The Book of Scotlands. By Momus

Solution 9: The Great Pyramid. Edited by Ingo Niermann, Jens Thiel

![]()

It sounds almost absurdly audacious to propose a list of capital-S “Solutions” to the world’s problems, be they economic, political or otherwise. That’s why Ingo Niermann’s Solution series endeavors to do so with solutions that themselves verge on absurdity. Niermann, a novelist, edits the series, and writes many of the texts himself. The others are outsourced to the type of experts who aren’t usually consulted about solving geopolitical problems: writers, artists, and architects. Each of the nine books in the series homes in on a particular geographic region, and each chapter corresponds to a specific proposal for fixing its most pressing issues. Solutions 186-195 address Dubai; 196-213 propose a “United States of Palestine-Israel”; 1-10 suggest the advent of “Umbauland,” a new and improved Germany. The proposals vacillate between the highly unlikely (a pyramid cemetery in the desert) and the startlingly feasible (welfare overhaul treated as a competitive sport). It’s this uncanny valley they create between science fiction and pragmatism – between irony and earnestness – that makes them so provocative. The most recent book in the series shifts its focus to a less tangible country – perhaps the world’s most vast and uncharted territory: Love. (ew)

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

Never Modern

Irenée Scalbert and 6a Architects; 1st edition, 2013

English

Paperback

176 pages, 64 b/w illustrations

14 x 21 cm

ISBN 978-3-906027-24-1

![]()

This book is an introduction to the work of 6a architects, one of the most interesting of the newer crop of UK practices. As opposed to a typical monograph, it has the look and feel of a novella or collection of poetry. And indeed the beautifully-written text inside – an essay by the architecture critic and historian Irénée Scalbert based on his conversations with the practice’s two directors, Tom Emerson and Stephanie MacDonald – reads more like a short-story: the narrative of a practice.

6a are generally seen as heirs-apparent to ‘The Whisperers’: the loose grouping of architects around Tony Fretton, including Caruso St John and Sergison Bates – with the work of Alison and Peter Smithson as their lodestar – an influence on their practice that is explored, alongside that of artist Richard Wentworth and the films of Jacques Tati.

Bricolage is taken here to be a guiding tactic behind 6a’s practice rather than any pre-ordained totalizing conceptual or theoretical position. And withal this is set against a keen sense of the passage of time, of a building’s history and future life. Whilst beginning by stating that the name 6a does “not presume an attitude”, by getting under the skin of the practice, this book identifies a strong sensibility to their work, making it seem akin to a manifesto-in-the-making, if a very readable and poetic one. (rw)

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

-

VEINS

Infrastructure and flow...

![]()

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»I don’t mistrust reality of which I hardly know anything. I just mistrust the picture of it that our senses deliver.«

Gerhard Richter

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents