-

Radical

PedagogiesArchitectural education in times of disciplinary instability

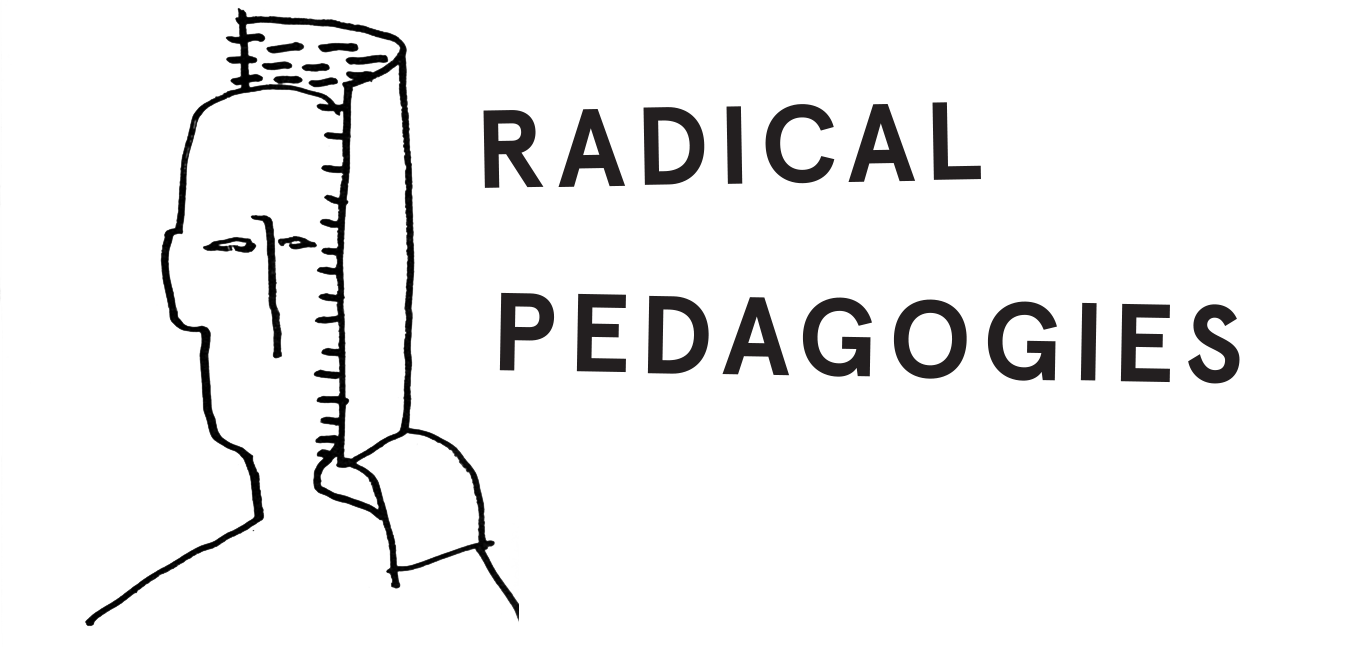

The nomadic school “Global Tools” was founded in Italy‚ 1973‚ by members of the Radical movement. This image shows a performance by Superstudio at a Global Tools meeting in Sambuca Val di Pesa, Florence, in 1974. From left to right: Angiolino Lepri, Adolfo Natalini, Fabrizio Natalini, Roberto Magris, Gino Lepri, and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia. (Image courtesy Adolfo Natalini)

-

The ongoing Radical Pedagogies research and exhibition project, first presented in 2013 at the Lisbon Triennale and then developed for the 2014 Venice Biennale, explores a series of pedagogical experiments that played a crucial role in shaping architectural discourse and practice in the second half of the twentieth century. Operating as small endeavours, sometimes on the fringes of institutions, these experiments questioned, redefined, and reshaped the post-war field of architecture and challenged normative thinking. Much of architecture teaching today still rests on the paradigms they introduced. uncube asked the project’s research collective to choose their five favourite radical pedagogies.

Giancarlo de Carlo debates with Gianemilio Simonetti as protesting students take over the Milan Triennale in May 1968. (Photo: Cesare Colombo)

-

Global Tools

Florence and Milan, Italy (1973–1975)

—

Active from 1973 to 1975 and founded by the members of the Radical movement, the nomadic school Global Tools explored architecture as a primordial creative act. As a nomadic school, Global Tools was founded in the editorial office of the magazine Casabella at the beginning of 1973. The collaborative project and magazine of the same name replaced the urban installations of late 1960s Florence with “didactic laboratories” open only to its members. Challenging the more canonical understanding of architectural pedagogies, the group’s aim was to learn from the “archaic wisdom” of the uomo de-intellettualizzato, or de-intellectualised man.

The focus was on artisanal methods of production, the employment of “poor” materials, and the ritual aspect of using handcrafted objects. As an alternative to industrial methods, handcrafted production offered a way to rethink the act of both conceiving and making an object. What was at stake was the generative act of production at large and the industrialised systems that they wished to overhaul. For Global Tools, the central task for architectural education was to ask why and how humans instinctually create. p (Federica Vannucchi)

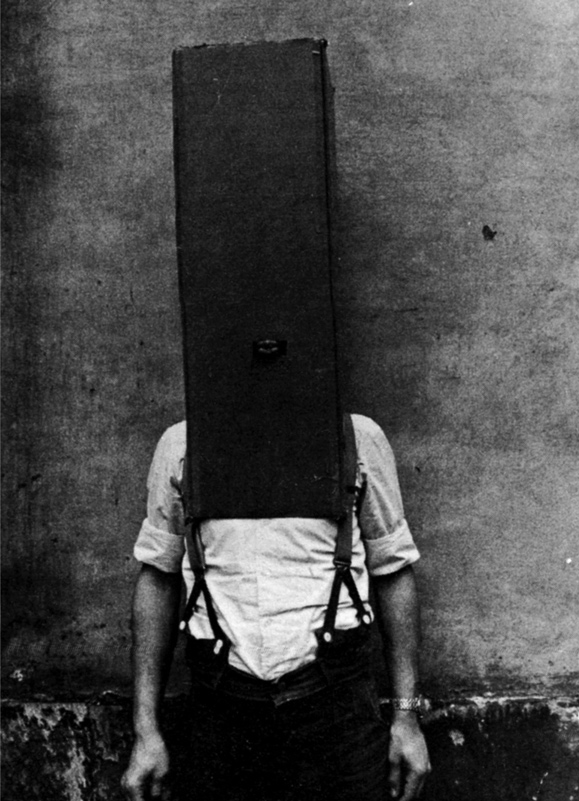

“The Body and its Restraints”, Global Tools performance by Franco Raggi‚ Gruppo Corpo‚ Milan 1975; from Casabella 411 (1975).

-

The Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis (LCGSA)

Harvard GSD, Cambridge MA, USA (1964 –1984)

—

The Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis at Harvard GSD (LCGSA) was one of the first radical, long-lasting institutions to introduce the computer as a tool across all the design disciplines. It operated as part of the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) between 1965 and 1991. Initially affiliated with the department of Regional and City Planning, it was founded by Howard Fisher as an experimental venue for the use of computers in the creation of maps. The lab also conducted courses, workshops and conferences. Despite the technical advances with which it is often credited (such as the “invention of GIS”) the pedagogical innovations of the LCGSA have been often overlooked.

The LCGSA members included architects, geographers, cartographers, mathematicians, computer scientists and artists. They believed that computer use in academic settings could profoundly alter the ways in which design disciplines operated. Alongside its ground-breaking and multi-faceted work, the lab’s experiments consistently raised questions about the practical ways in which computing could be of immediate relevance to the education of young designers, especially architects. p (Evangelos Kotsioris)

LCGSA student going through the steps of creating a computer map with the SYMAP programme.

-

Learning from Levittown Studio

School of Architecture, Yale University, Connecticut, USA (1970)

—

The “Learning from Levittown” studio course taught by Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi was radical not only in form, but in teaching content as well. It applied the innovative and collaborative “learning from” style of pedagogy for students to explore the world of suburbia. Following their “Learning from Las Vegas” studio in 1968, Scott Brown and Venturi conducted this studio in the spring of 1970. Venturi recalls the scandal that arose during the class final review: “We forget how much suburbia was despised at the time by the idealists”.

Scott Brown and Venturi treated architecture as a form of media. The course focused on how the inhabitants of Levittown decorated the exteriors of their own houses and also the way in which houses were represented in television commercials, home journals, car advertisements, cartoons, films, and even soap operas.

The course took place during a time of both urban and educational unrest. In the spring of 1970, there were big protests in New Haven: The Black Panther trials were in progress and there were riots in the city and rallies at Yale. The School of Architecture building was burned down, allegedly by students, the spring before, so the studio had to be held in a provisional building. p (Beatriz Colomina)

The Architecture School at Yale University was burnt down‚ allegedly by students‚ in 1969.

-

Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) Ulm

Ulm, Germany (1953–1968)

—

Moving off the grid both geographically and ideologically in 1953, the founders of the Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) in Ulm hoped to create a fundamentally different approach to design education that could re-democratise Germany after the war. Their highly rationalist approach was rooted in humanist functionalism aiming for “good design” to improve society. The HfG saw itself as an institution of dissidence in a country that was myopically rebuilding its cities yet failing to engage critically with its past. The school not only reformed architectural pedagogy but treated architecture as scaleless object of design – no distinction was made between shaping buildings and forming teacups or stools.

Expanding the Bauhaus notion of placing architecture at the centre of its curriculum, the HfG ultimately designed the design process itself. For this “process design”, the school set up its curriculum with theory and practice as equal parts, inviting mathematicians, sociologists, writers, and philosophers for guest lectures and seminars. Despite the school’s dedication to experimentation, its protagonists firmly believed in institutional frameworks for such explorations. Their experimentation created a paper trail – the meetings and institutionalised debates questioning pedagogy were transcribed, typed with several carbon copies, disseminated, and filed. In Ulm, radicality was institutionalised, or rather, institutionality was radicalised. p (Anna-Maria Meister)

Top: Reyner Banham (left) with Tomas Maldonado at the HfG in 1959. Bottom: Charles Eames (right) in conversation with Max Bill at the HfG in 1955. (Photos: HfG-Archiv‚ Ulmer Museum)

-

Architectural education in a time of disciplinary instability is the research topic of Radical Pedagogies. It is an ongoing collaborative research project set up by Beatriz Colomina together with PhD students at the Princeton University School of Architecture where she teaches architecture history and theory. Radical Pedagogies focuses on radically new models and experiments in architecture education in the second half of the 20th century. So far it has involved three years of seminars, interviews, archival research, guest lectures and contributions by protagonists and scholars from around the world. Currently on show as a part of the Monditalia section at the 14th International Architecture Biennale in Venice, it has been awarded with a Special Mention.

Escuela y Instituto de Arquitectura

Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile (1952–1972)

—

The Valparaiso Architecture School offered both an elaboration on the intellectual project of modernity and a response to modern architecture. Led by the Chilean architect Alberto Cruz and Argentinean poet Godofredo Iommi, its pedagogy drew from a wide set of references within the avant-garde. Exercises initially pursued plastic explorations, which were developed through "poetic acts" and the so-called phalanes – which oscillated between public recitations of poetry and collective artistic performances including games, garments and other plastic manifestations. The phalanes were intended to load spaces with meaning and open them to the creation of new subjectivities. They questioned any “instrumentalisation” of architecture, dismissing the modern emphasis to "change the world" to pursue instead a “change of life”.

This pursuit obliterated the boundaries between learning, working and living, in a destabilisation of pedagogical structures that eventually led students and faculty taking over the school in 1967. Their protests against the university authorities resonated with those that shook institutions globally one year later, though the School members set themselves apart from the political emphasis of the 1968 revolts. In Valparaiso, this destabilisation of the university ultimately resulted in the foundation of the experimental living and working space Open City, which was built by students and faculty starting in 1971 to further test the boundaries of architecture. p (Ignacio González Galán)

Tournaments in the course “Culture of the Body”‚ 1975. (Photo: Archivo Histórico Jose Vial)

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Architectural interpretations accepted without reflection could obscure the search for signs of a true nature and a higher order.«

Louis Isadore Kahn

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents