-

Architectural

Gifts

On the exhibition Charles Correa: India’s Greatest Architect, and the arrival of the architect's archive in London

Text by Vicky Richardson

Timber model of the Hindustan Lever Pavilion, part of Charles Correa's archive that has been gifted to the RIBA in London. (Photo: Wilson Yao, courtesy RIBA)

-

Installation shot of the exhibition “Charles Correa - India's Greatest Architect.” In the background, the two-metre-high timber model of the Kanchanjunga Apartments in Mumbai. (Photo: Wilson Yao, courtesy RIBA)

Installation shot of the exhibition “Charles Correa - India's Greatest Architect.” In the background, the two-metre-high timber model of the Kanchanjunga Apartments in Mumbai. (Photo: Wilson Yao, courtesy RIBA)The retrospective of Indian architect Charles Correa currently at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), set to tour internationally, draws on the architect’s extensive archive, which he recently gave to the British Architectural Library, documenting Correa’s career over 65 years. Earlier this year the collection of 6,000 drawings, documents, photographs and models arrived in London, where it will be cared for by the RIBA. The exhibition shows reproductions of drawings, photography and some magnificent models. Ironically, original drawings are not able to be included as, until the RIBA’s new gallery is complete at 66 Portland Place, the Institute does not have the controlled conditions required to display them.

The gift is the most substantial ever received by the Institute from a non-British architect. For Correa the decision to send his archive overseas must have been an extremely difficult one. “India’s greatest architect” – to quote the subtitle for the exhibition – has devoted his career to India, and has contributed beyond measure to the design of its housing, important public buildings, and cities. -

»Correa’s principles are universal yet highly rooted in site.«

Most importantly, Correa has been engaged in a constant effort to define an alternative path for post-colonial and contemporary Indian architecture. There is no little irony that an architect whose work is so strongly rooted in a place should send his archive to London, a city that these days is a hub for a type of global architecture – an anathema to Correa’s work. But at the RIBA it will be well cared for, and most importantly for Correa, it will be accessible to students and architects from around the world.

The exhibition focuses on a selection of projects from more than 115 documented in the Correa archive, as well as expressing some of the architect’s important guiding principles. Correa’s work strikes a delicate balance between responding to the specifics of site – “representing the truth of the place” as he puts it – and certain firm principles, such as “the empty centre” and the ritualistic pathway. The latter is a device regularly employed by Correa to create a sequence of different atmospheres and ideas within a single building, providing a narrative about the diverse influences on Indian architecture.

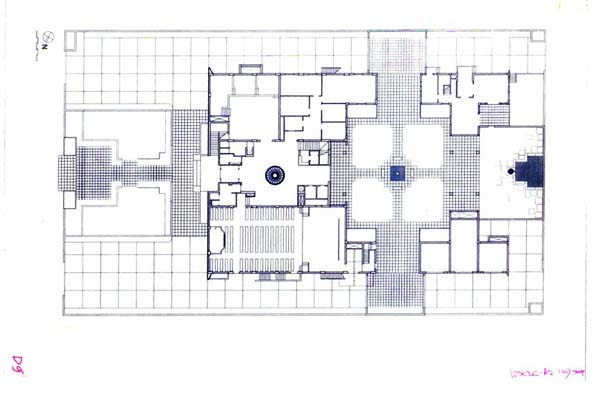

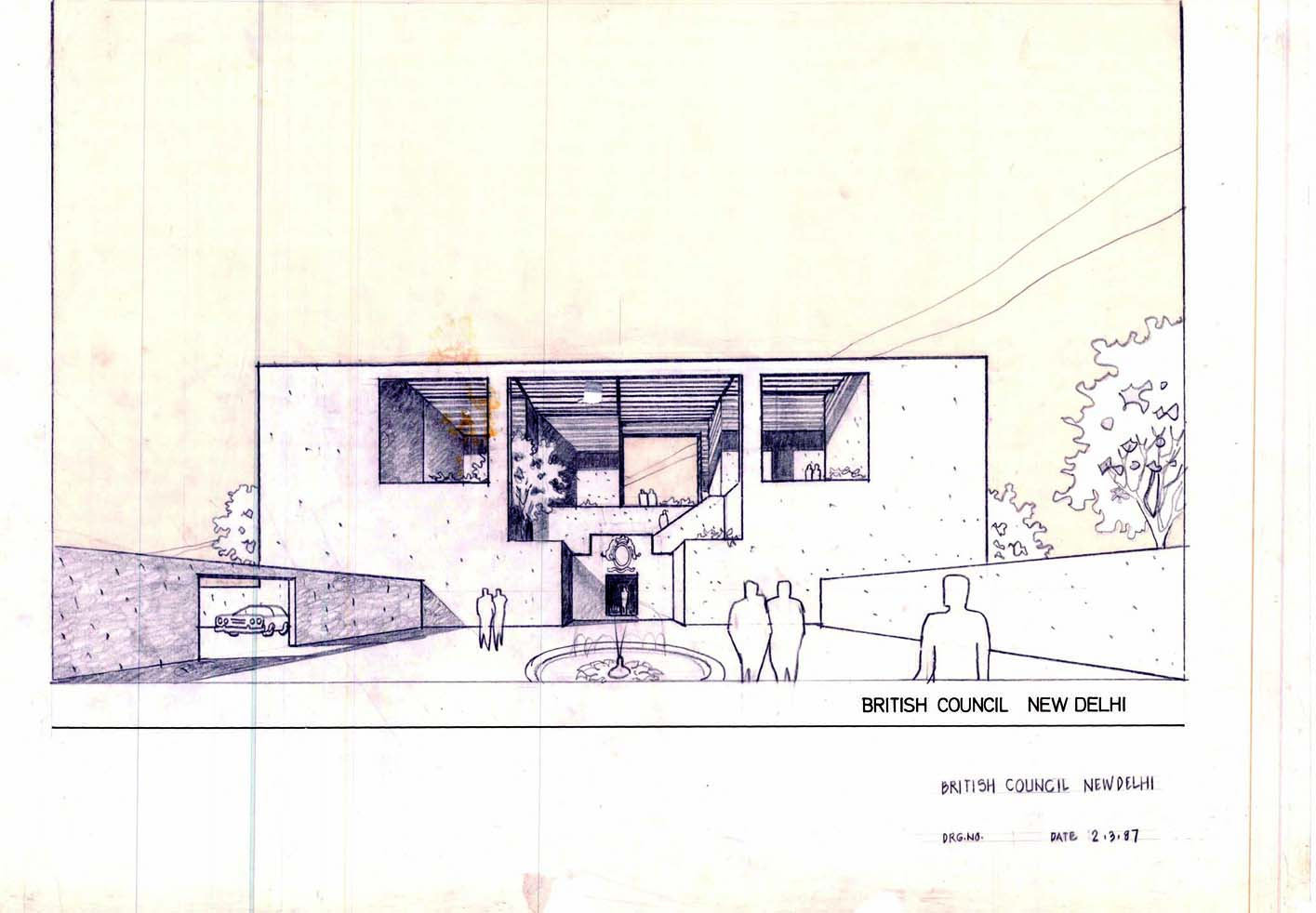

Correa’s principles are universal yet highly rooted in site. His design for the British Council building in New Delhi, completed in 1992, is a wonderful example of this dichotomy. In the exhibition it is represented by a roughly-made, but beautiful foam-board model. A black-and-white photocopy of a mural by Howard Hodgkin is glued to the layered façade, possibly resulting from the conversation between architect and artist as the design evolved. The British Council would have given Correa a pragmatic brief for the building, but he took the opportunity to make a profound comment about the historical influence of external belief systems on Indian culture in a way that reconciles them and presents India – and Britain – as open-minded and tolerant.

In his lecture at RIBA in May, Correa poetically described the layering of culture and ideas in the project, and the wider relationship of architecture to art, film and sculpture. “Architecture is sculpture,” he asserted, “but it also needs to be used by human beings. Doors and windows shouldn’t diminish it, but should complete it.”

-

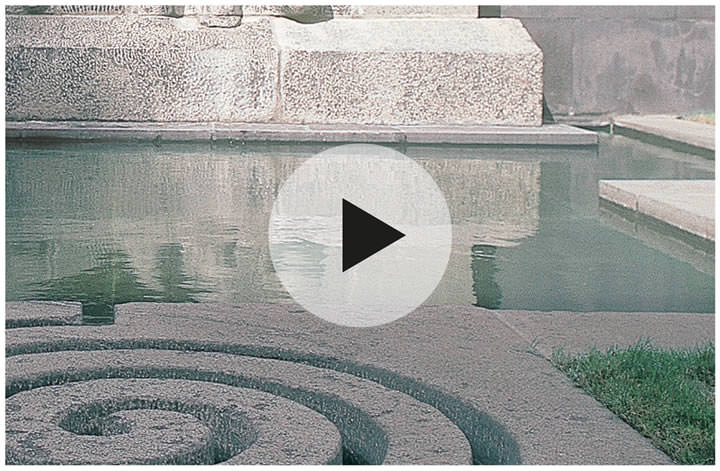

View of a sculpture by Stephen Cox installed in the British Council building in New Delhi. Correa’s idea for the building was to express the three basic cultural identities that have shaped contemporary India: Hindu, Muslim and European. He accomplished this by creating three separate courtyards. Cox’s sculpture sits in the Hindu court, at the point of “Bindu,” or unity. (Photo © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

Charles Correa in conversation at the RIBA in London with RIBA President Angela Brady in May 2013. (© Video Productions Ltd/RIBA)

-

View across the inner courtyards, with in the foreground an interpretation of the layout of the Islamic Garden of Paradise.

The building façade is red Agra stone. (Images this page courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

Detail of mural by British artist Howard Hodgkins on the main façade, made of black kuddapah stone and white makrana marble.

Correa’s architectural models in the exhibition convey a great sense of conviction and confidence, as evident in the early projects as in the later years. A sectional timber model of his Tube House in Ahmedabad, built in 1961-62, describes the simplicity and strength of the building. It was an early example of Correa adapting his modernist training to consider local climatic conditions. His skillful manipulation of a building section is seen later in the remarkable Kanchanjunga apartments, completed in Mumbai in 1983. Here Correa subverts the traditional principles of a bungalow veranda and applies them to a high-rise, creating generous two-storey terraces within geometrically-complex interlocking apartments. There is nothing predictable or easy-going about Correa’s architecture or his attitudes. His intellect is kept sharp by the culture of Indian society itself, which embraces debate as it deals with striking paradoxes and constant change.

-

British Council, New Delhi. The ground floorplan shows the axis running through the building, from the entry off the street on the left through the main building entrance.The view looks back along the axis from its culmination in the Hindu Courtyard. (Images © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

-

Vicky Richardson is Director of Architecture, Design and Fashion at the British Council. She was previously Editor of Blueprint magazine and Deputy Editor of the RIBA Journal. She is a member of the London Mayor’s Cultural Strategy Group and Co-Director of the London Festival of Architecture. She has a degree in architecture from the University of Westminster and studied fine art at Chelsea School of Art and Central St Martins.

Design drawing for British Council from the Charles Correa archive. (Images © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

»There is nothing predictable or easy-going about Correa’s architecture or his attitudes.«

A throwaway remark by the architect during his lecture, showed that for Correa the most significant projects of his career have been in housing and urban design. Museums are “culture-free, unlike housing,” he said. The RIBA’s exhibition and accompanying public programme, give a strong flavor of the potency of debate on architecture in the sub-continent, but left me wanting more. In particular, the inclusion of Correa’s working and presentation models – such powerful evocations of his design principles - made the absence of original drawings even more disappointing.

Importantly Correa’s gift to the RIBA does not mean the key to his working process will be inaccessible to Indians. Before packing up the archive, Correa spent a year turning every single item into a digital file, and the resulting digital collection will be freely accessible in Mumbai and New Delhi. Contributing to an ongoing debate about modernity in India is vitally important to him. In the closing remarks of his lecture, Correa summed this up beautifully: “It will take time for the confidence to come back to a great civilization that lost every battle for 1,000 years. In India we have to reclaim modernity for ourselves. The whole world has a right to be modern – it’s not a style, it’s an attitude.”

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Form follows feminine.«

Oscar Niemeyer

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents