-

Mainland shift

Charles Correa and the Making of Navi Mumbai

In 1964, Charles Correa, Pravina Mehta, and Shirish Patel proposed a radical re-structuring of Bombay – a city whose infrastructure was collapsing under the weight of an exploding population. Their design was no small invention, and today it’s recognized as a true feat of big-scale urban planning.

Text by Julian JainPanoramic view over the lake to Nerul, Navi Mumbai. (Photo: Julian Jain)

-

View of the hills around Matheran, Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR). (Photo: Julian Jain)

In geographical terms, the city of Mumbai is that rarest of places: a city far out at sea, emerging like a mirage above the waves. It floats on a narrow tongue of land, surrounded by water not on one or two, but three sides. The sea defines Mumbai, perhaps like no other city in India or indeed in the world. Throughout the city’s history, the sea has shaped Mumbai, encompassing its economic basis as a port and centre of maritime trade, its skills and employment, its settlement and mobility patterns, as well as its relations with the neighbouring mainland and other regional inland locations.

Originally situated on a handful of small islands around fifteen kilometres from the nearest mainland shore, in the late eighteenth century the city was joined by land reclamation to the larger Salsette Island in the north by the British. Mumbai, then called Bombay, spread from its colonial centre in the south towards the north in several developmental waves. The city’s original centre included its port, fort, docks, merchandise warehouses and subsequent business districts, neighbouring cotton mills, a railway terminus and other public institutions, most of which were built in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

-

The practice of simply extending the city’s boundaries further north while retaining the high concentration of jobs on the reclaimed southern promontory was more or less successful for much of the eighteenth to mid-twentieth centuries. However, by the early 1960s things were reaching a critical pitch. Bombay’s population growth was exploding, driving up prime real estate prices in the south and threatening to push much of the city’s poorer and lower-middle class population – the backbone of the city’s workforce and wealth generation – out into ever more distant suburbs in the north. The city was quickly turning into an urban “sprawl machine” attracting more and more migrants. This led to the rapid growth of the informal sector and formation of slums in inner-city locations, as many workers preferred to live in inner-city slums rather than in proper accommodation in far-away suburbs. At the same time, the two main north-south commuter train lines were becoming dangerously congested. The city was becoming the most densely inhabited place on the planet with some of the lowest open spaces per capita.

With extensive harbouring for ships and a local train network to ferry around both the population and the goods to service it, Navi Mumbai is well connected into the wider city of Mumbai and beyond. (Photos: Julian Jain)

-

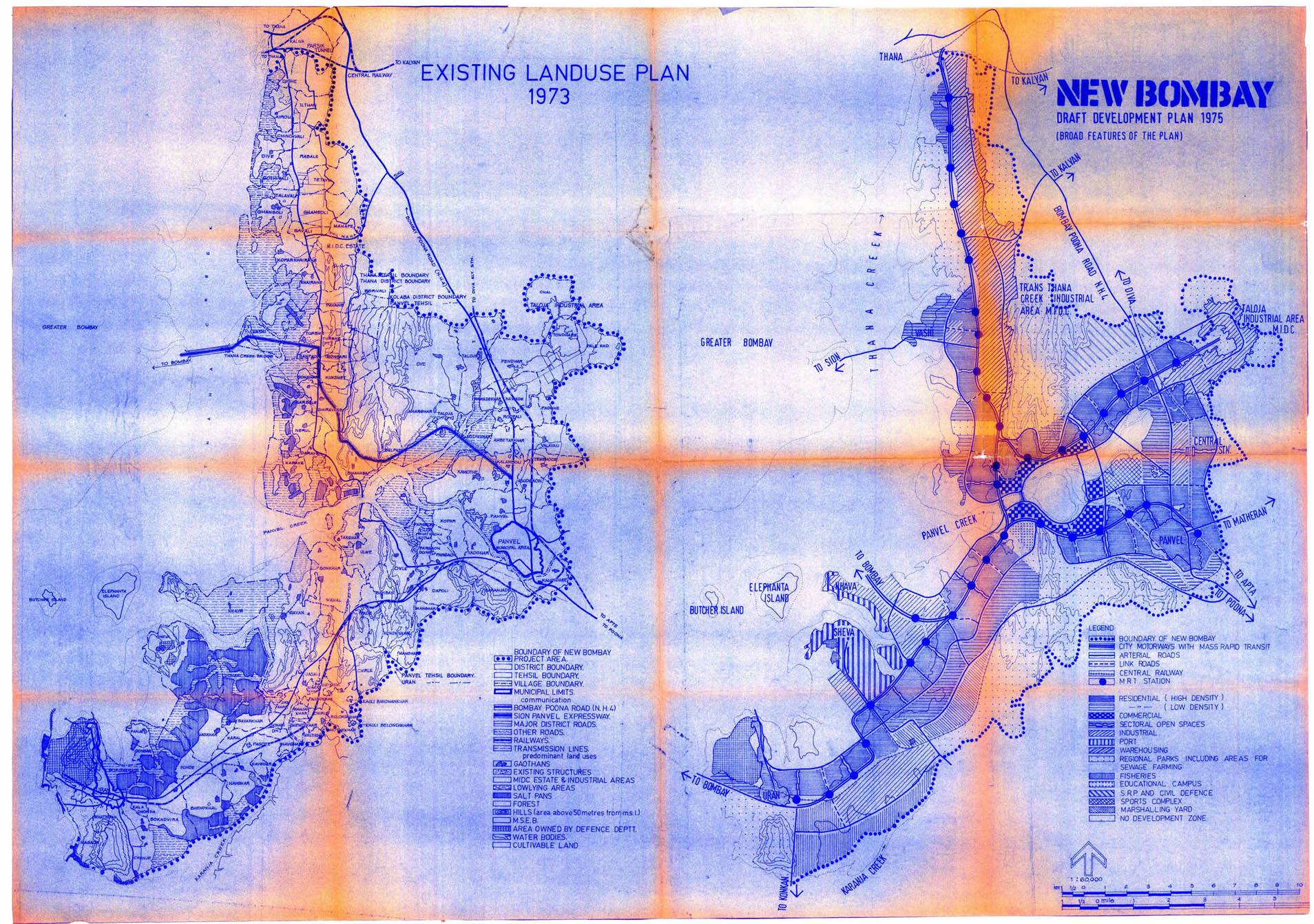

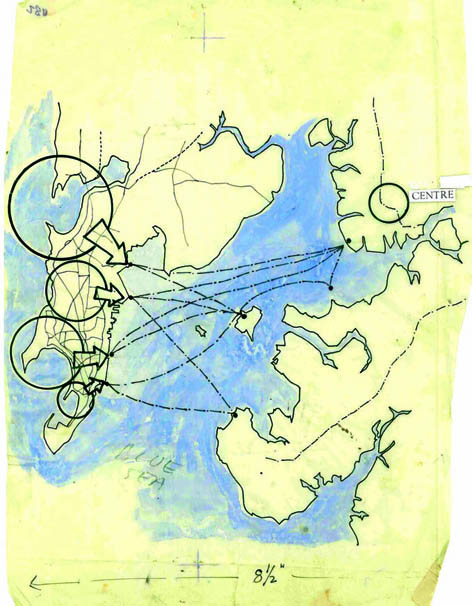

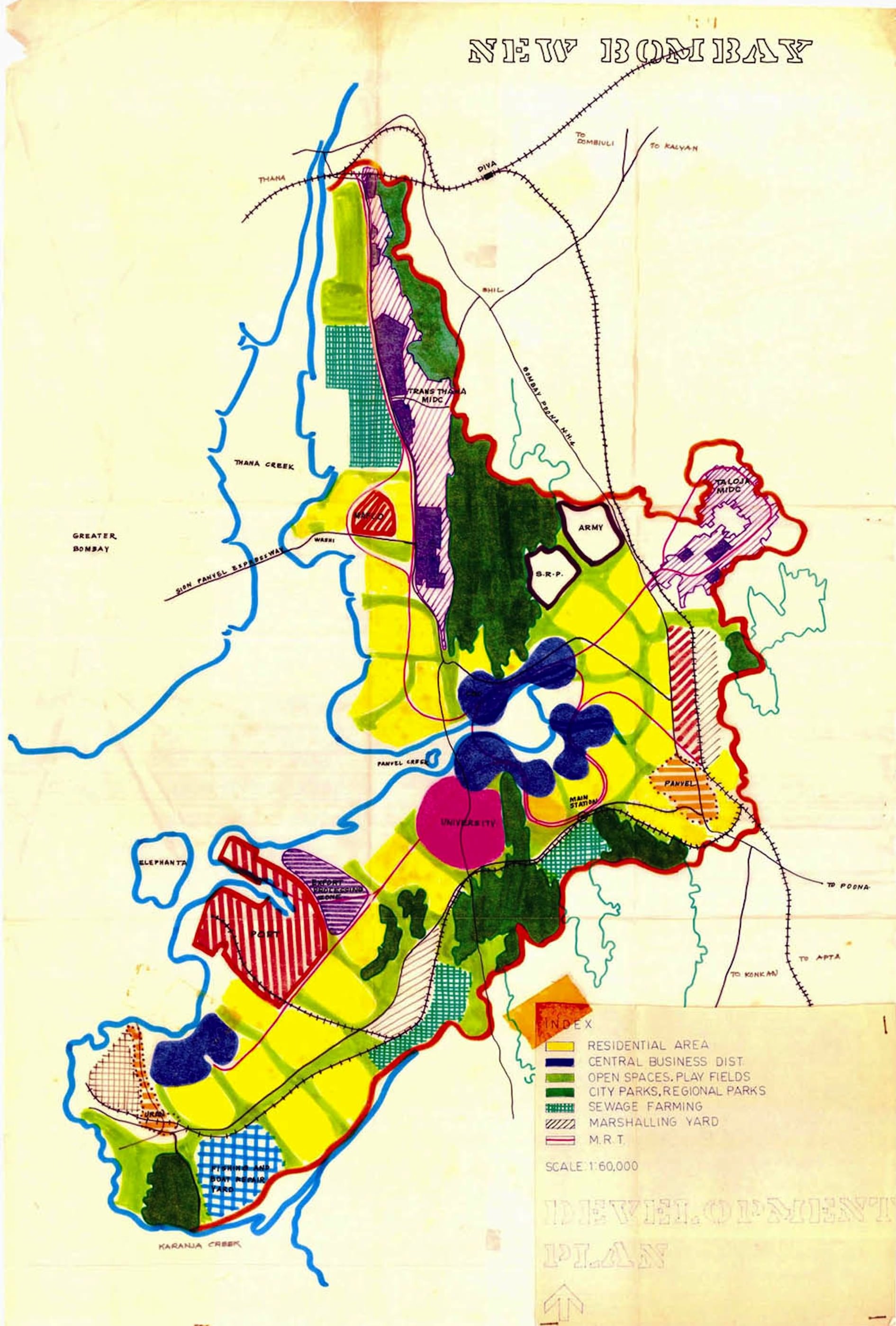

Development plans for Navi Mumbai from the Charles Correa archive. (Images © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

Bombay’s population jumped from 1.5 million in the years leading up to the Second World War to 4.5 million in 1964, and was predicted to double by 1984. By 1965, municipal limits had already reached the northern end of Salsette Island – today’s suburb of Mira Bhayandar – meaning that the city sprawled over a continuous 45-kilometre stretch from the south to the north. The very advantages that the sea and land reclamation had offered Bombay were rapidly turning into an unmanageable burden. There seemed to be no practical conception of how to deal with this self-perpetuating “one-way street” of urban development, had it not been for the vision of Charles Correa.

Along with two of his colleagues, Pravina Mehta and Shirish Patel, Correa submitted a memorandum to the Bombay Municipality in 1964, suggesting to re-structure the north-south developmental pattern into an east-west one centred around Bombay Harbour. The proposal would also integrate the areas on the mainland rim, some 20 kilometres east of the old centre of Bombay, into a new polycentric urban structure.

This was innovative thinking. It opened up entirely new perspectives on the future development of Bombay and its hinterland, and represented the first concerted effort at decentralising the urban functions of Bombay. Following much public support and extensive deliberation, the basic proposals were accepted by the state government in 1970. A new city was to be planned, called New Bombay, which would eventually become the largest planned city of the twentieth century.

-

Incremental Housing, Belapur, New Bombay/Navi Mumbai, 1983-86

This development is located on six hectares of land around two kilometres from the city centre. Consisting of seven houses grouped around a shared courtyard, each of which has its own piece of land, the complex is home to an entire social spectrum – from former squatter families to those in the upper income brackets – yet the sites vary little in size, each between 45 and 70 square meters. The houses’ simple floorplans can be incrementally expanded by local masons and craftsmen – thus generating employment in the urban economy exactly where it’s needed. This is an example of one of Correa’s innovative housing solutions for the region, that also with adaption could have a much wider application as an idea. (Photos © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

-

A specially-created state agency, the City and Industrial Development Corporation of Maharashtra, or CIDCO, was tasked with designing and developing the new city. Charles Correa was appointed Chief Architect to CIDCO from 1970 to 1974. While the old Bombay and its burgeoning suburbs were threatening to sink like a ship under its own developmental weight, an anchor onto the mainland had been thrown.

The city plan that Charles Correa envisioned was intended to diversify and decentralise growth and employment around Bombay Harbour, and to ease the burden on a city that was becoming increasingly congested. New Bombay was planned for two million inhabitants. The city was structured around two arms along the eastern rim of Bombay Harbour and Thane Creek, meeting in the middle at the site of an envisaged new city centre around Waghavali Lake. Each arm was planned around several developmental nodes, from Airoli in the north to Uran in the southwest.

The innovative quality of New Bombay’s planning was underpinned by a focus on public transport, low-income housing, rainwater harvesting, and responsive urban form typologies, including high-density, low-rise typologies. Originally planned as a “twin city” to Bombay, New Bombay, now called Navi Mumbai, has the potential to become a locus in a network of other cities and towns within the wider Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) that includes around 21 urban centres and 1,090 villages on an area of 4,355 square kilometres, with a total metropolitan population of around 21.9 million.

New constructions in Belapur, Navi Mumbai. (Photos: Julian Jain)

-

»The innovative quality of New Bombay’s planning was underpinned by a focus on public transport, provision of low-income housing, and development of responsive urban form typologies.«

View to recent constructions, showing the lush coastal environs of Navi Mumbai. (Photo © Julian Jain)

-

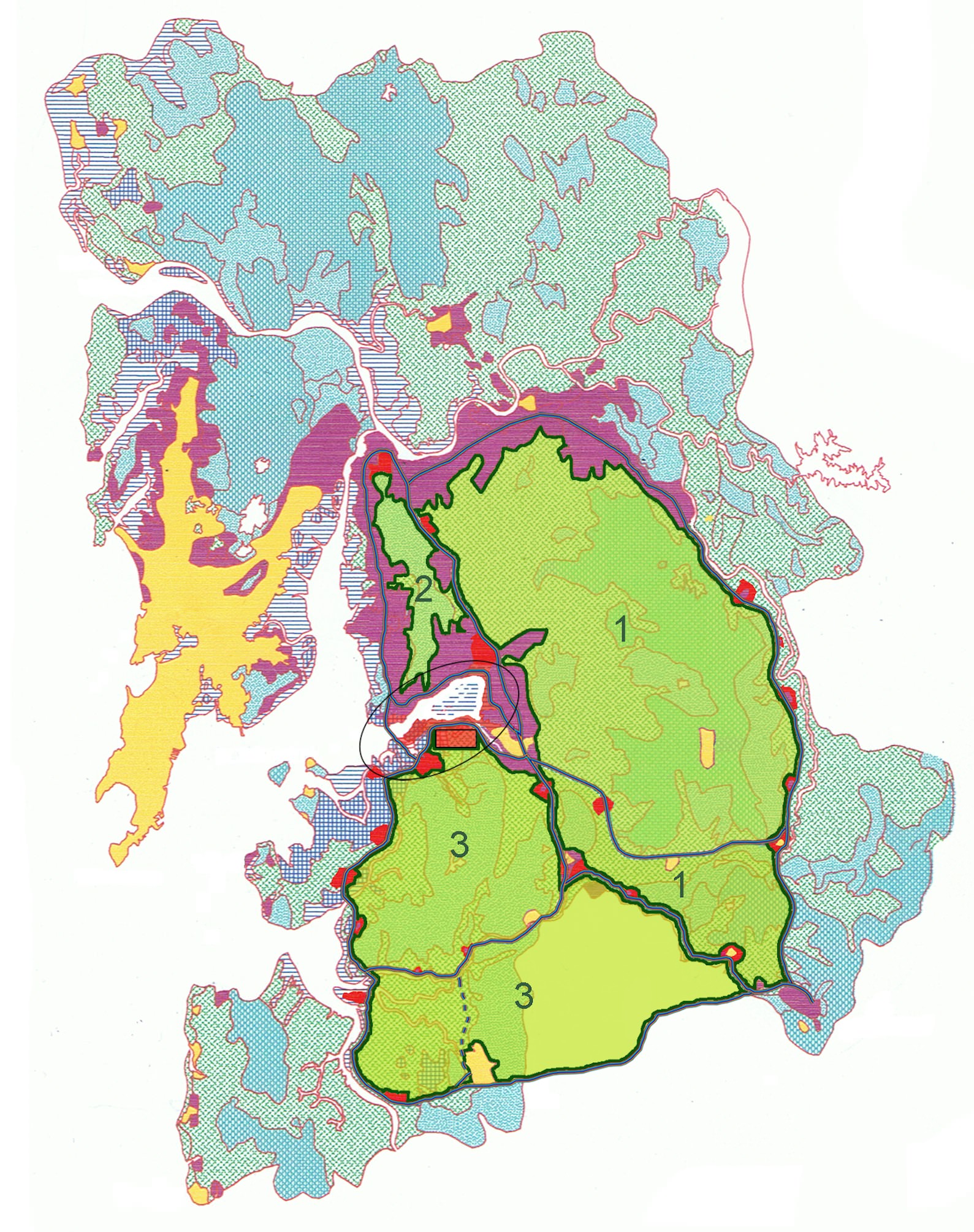

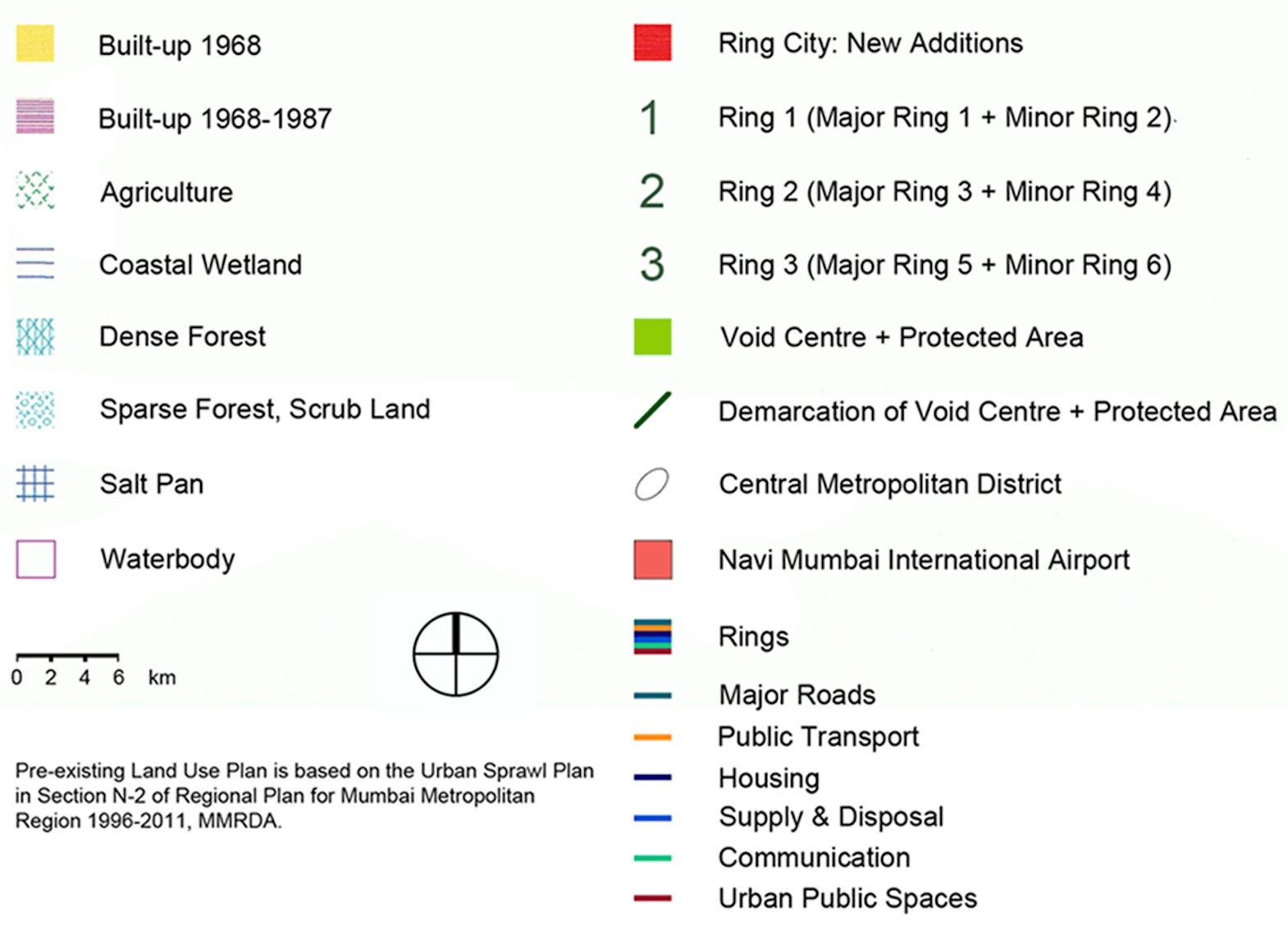

Photo from the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) of boats at low-tide, in an area which has been subject to a rethinking of land-use patterns and change. A recent land-use proposal for the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) re-imagining it as a series of three “void centres” with corresponding “ring cities,” based on proposals by Julian Jain, Berlin, and von Gerkan, Marg and Partners (gmp), Hamburg, 2009. The underlying land-use plan here is based on the Urban Sprawl Plan, part of the Regional Plan for Mumbai Metropolitan Region 1996-2011, Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA), Navi Mumbai. (Photo and graphic: Julian Jain)

-

Julian Jain is an architect and urban geographer. His research focuses on megacities and metropolitan regions of the South, and sustainable urban and regional development. His most recent publications include “Region of the Rings, Cities of the Void” in DOMUS India, vol. 1, issue 10, Mumbai, September 2012, and “Mumbai, the megacity and the global city: A view of the spatial dimension of urban resilience” in Institutional and Social Innovation for Sustainable Urban Development, Routledge (Earthscan), Abingdon, 2013.

Sources for this article include:

• Charles Correa, Housing and Urbanisation, Urban Development Research Institute (UDRI), Mumbai, 1999.

• City and Industrial Development Corporation of Maharashtra Ltd. (CIDCO), 2005 Survey, CIDCO, Navi Mumbai, 2005.

• Julian Jain, “Region of the Rings, Cities of the Void” in: DOMUS India, vol. 1, issue 10, Mumbai, September 2012.

• Julian Jain, Fritz-Julius Grafe, Harald A. Mieg, “Mumbai, the megacity and the global city: A view of the spatial dimension of urban resilience” in: Institutional and Social Innovation for Sustainable Urban Development, Routledge (Earthscan), Abingdon, 2013.

• Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA), Regional Plan for Mumbai Metropolitan Region 1996-2011, MMRDA, Mumbai, 1999.

• Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation (NMMC), About Navi Mumbai. (accessed 23rd April 2012).

• Population Census of India 2011, Provisional Population Totals. (accessed 14th May 2012).

• Sonja Ernst, Dossier Megastädte: Mumbai – Aufstieg zur Weltklasse, Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (BPB), Bonn, 2006.

In creating Navi Mumbai, Charles Correa expressed in urban planning and form the themes he also cherished and reflected in his architecture: incremental growth possibilities; symbiotically linked and open-to-sky spaces; high-density, low-rise typologies; a focus on the pedestrian and public transport; and the generation of local skills and the use of local building materials.

Navi Mumbai has grown considerably since its beginnings in the early 1970s. Around 30 percent of its households have relocated there from southern Mumbai, underlining its growing attractiveness as a place to live and work. Though it took several decades for growth to set in, owing in part to the continuing functional primacy of Mumbai and the initial dearth of civic institutions in Navi Mumbai, the city today offers some of the highest living standards of any new town development in the country, with excellent housing, education, healthcare, and sports facilities, and a relatively dense public transport network. It has developed its own profile and mostly functions independently of Mumbai, buoyed by its own economic development. In effect, it cannot be considered a suburb of Mumbai; most people who work in Navi Mumbai today also live there.

Navi Mumbai’s population, approximately 1.1 million in 2011, continues to grow. Recent developments include a new container-shipping port at Nhava in Navi Mumbai, the largest in India, a new information technology “knowledge corridor” passing through Navi Mumbai along the Mumbai-Pune highway, a new special economic zone (SEZ), and a new international airport just south of Navi Mumbai’s city centre, to be opened by around 2015.

Navi Mumbai and Charles Correa’s vision behind it mark the beginnings of innovative, viable post-independence urban planning in India and stand as an inspiration to further endeavours in the field of sustainable urban and regional development, both in the wider Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) and other parts of India – as well as in the global South at large.

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»What the map cuts up, the story cuts across.«

Michel de Certeau: Spatial Stories

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents