A concrete industrial space converted into studios and a restaurant in one of Berlin’s periphery neighbourhoods – we've heard it all before, right? Wrong. With its snail-pace attitude to development, an ever-evolving architecture and a genuine social commitment to its surroundings, ExRotaprint is the antithesis of “maker space” gentrification hype. Following the recent publication of a monograph on the building’s architect Klaus Kirsten, uncube’s Fiona Shipwright headed to Wedding to see what all the fuss isn’t about.

Waiting is a word which often crops when Berlin’s Wedding district is mentioned, thanks in part to its seemingly permanent status as being “next”, now that areas such as Kreuzberg and Neukölln have seen the winds of gentrification blow through. In recent years though, visitors have indeed been increasingly venturing north to Wedding where one of the key photo opportunities on such expeditions is a remarkable piece of Berlin “brutalism”, a five-storey, raw concrete tower that sits on the corner of Gottschedstraße and Bornemannstraße.

Though a stunning piece of post-war architecture, it’s not actually brutalist and was never intended to look as such; instead, its rough exterior, which was meant to be plastered and then painted white was never finished, on account of two further storeys, planned as later additions, never being built. Once their architectural snap has been taken, those visitors who take the time to head through the gate just beside the tower will be rewarded by the discovery that it’s not just this building which is very special, but also the whole complex that lies behind it: ExRotaprint.

The brainchild of artists Daniela Brahm and Les Schliesser, ExRotaprint is, to put it very simply, a complex of space at a former manufactory site, which, before it was prefixed with “Ex”, belonged to Rotaprint, pioneering manufacturer of printing press machines used for offset printing, founded at the turn of the twentieth century. The various spaces at the site are available to rent in the service of Arbeit, Kunst, Soziales (work, art, community). Many such initiatives with similar goals exist, both in Berlin and beyond, but what is so extraordinary about ExRotaprint is the approach the artists have taken to both achieve and – crucially – maintain this outcome.

When I meet Brahm inside the doubled-glass fronted, beautifully restored environs of ExRotaprint’s flagship project space, which once housed a technical design office, she points to two smaller spaces at the back that are sectioned off by transparent glass walls. These are covered with paper because they’ve not been renovated yet. The paper has been there for two years because, as Brahm, explains, “We’re not in a hurry”. This is the ethos underpinning the whole ExRotaprint endeavour and the benefits of taking time, of waiting, are clear to see.

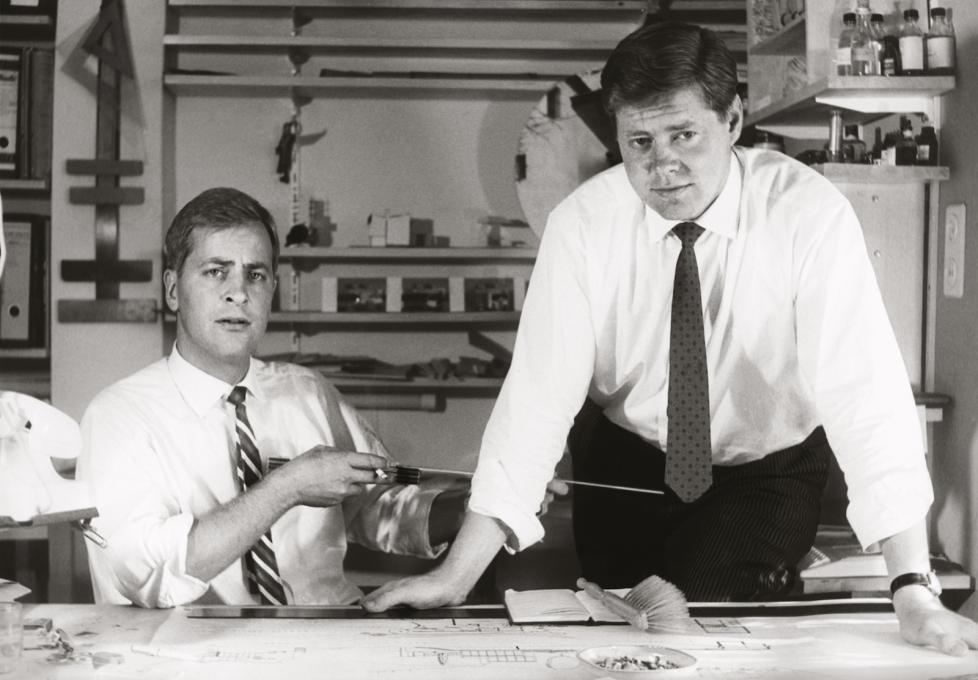

Both artists, Brahm and Schliesser see their model as an extension of their practice. In order to facilitate the functions of Arbeit, Kunst, Soziales (work, art, social), they have created a tripartite concept: a unique legal plinth, upon which sits a social sculpture, which functions as a Trojan horse. But to understand why the site is so special in 2016, one has to consider what happened there during the company’s mid-century boom years and how the quality of architecture that arose then would come to not only define but also help to secure the ExRotaprint operation half a century on. By the mid-1950s, with an expanded workface of 1000 and thanks in part to the West German economic miracle, Rotaprint was able to rebuild the site, which had been badly damaged in the Second World War. The company called on the services of architect Klaus Kirsten, one of the best German post-war modernists you’ve never heard of. Just a few years after he began work on the buildings in Wedding, Kirsten founded a partnership with Heinz Nather: Kirsten & Nather.

The rejuvenation of the ExRotaprint site in the 1950s resulted in a cluster of building arranged around a central courtyard. Looking at them today, they appear as a disparate mix of styles and periods but the assemblage is an arresting site, appearing clustered but not cluttered. Kirsten’s front tower, nestles up to the former assembly hall and office wing, all of which were completed in 1958. Heading into the courtyard, this left wing of buildings joins with a remarkable two-storey glass box designed by Kirsten, which enables light to pour in from both sites for those working in what was the company’s technical department and is now the aforementioned project space. On the other side, a nineteenth century Gründerzeit building that was once red brick but now wears a plain white façade, joins up almost seamlessly with the low-rise, single storey modernist structure at the other end. Kirsten also designed a rear tower (today, almost hidden by a Lidl and its car park) completed in 1959 and which sits on opposite corner from its blocky brethren. This too is unlike anything else that can be found in the surrounding area: its workshop and fabrication spaces are arranged as of a stack of concrete boxes, playfully piled atop each other.

The heritage status of the buildings, bestowed in 1991, concerns not just the pleasing visual collage they provide from the outside, but also the way in which the modern additions are all interiorly linked up with the previously existing buildings; firewalls join firewalls, the various expansions filling voids and spaces like a benign, curious parasite. This feature of the site deemed it notable enough to be listed, meaning it would require something from any prospective developers that they don’t normally like to give: patience.

When Rotaprint went bankrupt after German Reunification in 1989, though undeveloped and badly in need of upgrade work, its spaces were managed locally and rented out to a mix of renters. In 2002, the site it came into the hands of the Liegenschaftsfonds Berlin, a subsidiary of the (then equally bankrupt) city administration charged with selling state-owned properties. As with other similar sites in the city, Rotaprint was due be sold to whoever could lay claim to the biggest wallet and not necessarily who could offer the best provision of services and culture for the local area.

In 2005, having formed ExRotaprint e.V (a registered charitable association) as the representative body of the renters already on site, Brahm and Schliesser approached the Liegenschaftsfonds with a concept that would allow it to be taken over by those who were already there, who had already demonstrated the usefulness of the site and its ability to function well as a community of mixed users. It took several years of negotiations, almost thwarted by the interests of an Icelandic investor who was at one point due to buy up around 45 plots in the city but thanks to a huge amount of patience, determination and sheer bloody-mindedness, ExRotaprint e.V secured the site.

In order to ensure that it would never go on the market again, they decide to ground the site’s future operation on a “legal plinth” by firstly becoming ExRotaprint gGmbh – a non-profit organisation which saw all rents going back into the maintenance of the buildings – and secondly, by placing the ground upon which all the buildings stand under the ownership of the Edith Maryon Foundation and the trias Foundation, who both work to interrupt the typical, breakneck speed of property speculation.

In the end the whole complex was sold according to the land value, as if the buildings weren’t here: “it was a kind of unintentional mis-speculation by the Liegenschaftsfonds, who wanted to sell it quickly, which worked in our favour”, says Brahm, “We have a 99-year, heritable building rights contract with the foundations meaning we pay them an annual lease for the ground. We then own the buildings and can work with them without having to ask for anything. The only – very important – condition is that we can’t sell the compound because they own the ground. In taking the pressure off the site being sold, it allowed us to concentrate on the use of the spaces and its social impact”.

The nature of the social sculpture atop that plinth is best expressed by the fact that the current usage of the buildings reflects the variety of their form. Post-industrial, new-creative use is naturally a consideration here but ExRotaprint is much more than just community of artists existing in isolation with no connection to either the site’s history or the surrounding neighbourhood. Instead, the site is also home to education facilities, offices, and small business, all with links to the local community.

To neatly illustrate the point, Brahm tells me of a visit she paid to one of the apartment buildings directly opposite the entrance gate to ExRotaprint: “I wanted to take a photograph from one of the balconies as from there you can see the whole compound. A resident agreed and I spoke with her a little bit; those apartments are almost completely rented out to immigrants and she knew ExRotaprint not for any of its cultural activities or the canteen but because she was friends with a couple of people that had been to German classes here, knew people who had attended to the school here, and had visited the citizen advice services here. I found that so interesting because it means that people connect ExRotaprint with what it is meant to provide for them.”

That notion of reaching out is exactly what was behind the third element of the concept, as Brahm explains: “Art can be a way of opening doors, or it can be a Trojan horse: enabling processes that are generally viewed with mistrust and are easily dismissed.” The process by which ExRotaprint has assured its future was viewed with mistrust – perhaps even disdain – by some on the side of the city authorities. Yet in playing the long game, in choosing to wait, those behind it have proven, even in a city where speculation has reached fever pitch, that such a non-profit approach is possible.

Other initiatives, which draw upon the industrial heritage and prior life of a site, are developing in other cities – take for example the Old Vinyl Factory in West London, once the site of HMV’s production plant and soon to be “intelligently designed workplaces, entertainment venues, shops and homes in art deco landmarks and smart contemporary buildings” or New York’s Brooklyn Navy Yard, part of which is being developed into an “industrial” scale Maker Space. Both of the projects have admirable aims but reading through their press literature you become very aware of one thing which is conspicuously absent on any of that produced by ExRotaprint: a completion date.

In response to the question of whether there is such a thing, Brahm replies, without missing a beat: “No”. And the reason is so common sense as to almost be absurd: “It’s done when it’s done. There won’t really be a finishing point – yes, there are ‘completion’ dates for the purposes of investment calculation, but people are already here; the space is already rented out to many different kinds of users. In parallel, we will proceed with more renovation works, which of course furthers the project. Apart from that, the main thing is to ensure space is rented out to the people that make sense for the district, that do things that offer something to the area – that work shouldn’t stop, it goes on.” Describing architecture as “timeless” tends to be fairly meaningless. In the case of ExRotaprint, it means everything.

Kirsten & Nather - Wohn- und Fabrikationsgebäude zweier West-Berliner Architekten, Edited by Daniela Brahm, Les Schliesser/ExRotaprint, is published by Hatje Cantz, 2015.