It’s fair to say that in recent years, Greece has provided ample material for anyone working within the field of documentary photography. But for Yiorgis Yerolymbos, who contributed the stunning Athens Nowhere series to our issue dedicated to Athens, photography - and in particular architecture photography - has also been an important tool in ensuring those last few years do not come to define contemporary impressions of Greece. He spoke to uncube’s Fiona Shipwright about avoiding ruin porn, shooting Renzo Piano and his continued fascination with “human-altered landscapes”.

You have a background not only in photography but also architecture – how has this influenced your practice as a photographer?

Studying both architecture and photography has shaped the way I perceive the world in a number of different ways. According to Edward Weston American, who photographed modernity during the 1930s, the photographer seeks Form: a kind of balance amongst shapes, lines and volumes. That is peace. The architect, on the other hand tries, to understand how things work – their function – and their combined expression in form. I would consider this a powerful combination of tools when attempting to decode the complexity of the world and trying to discuss its meaning through visual interpretation.

How have you seen the effects of recent crisis manifest themselves in architecture whilst shooting buildings across Greece, beyond Athens? Would you say that architecture is perceived seen as a superfluous activity in the country, or as a provider of solutions?

Architecture has always tried to provide solutions and improve the life of its everyday users. Some buildings are designed to gratify their designer's ego, and can therefore be considered as superfluous, but the great majority are not. The crisis in Greece deeply affected architecture by forcing the cancellation of numerous projects and postponing many others indefinitely. Architecture could provide considerable solutions that would improve our quality of life in the near future, but certainly not for the time being. In my opinion, as a society we are still deeply entrenched in the current crisis and are unable to permit any single discipline to help us. We will welcome such solutions once we have passed from the mourning stage to that of understanding and eventually acceptance of the reality. Then I am confident that architecture will be able to extend a helping hand.

You’ve photographed landscapes, protest rallies, a series on Greek banks, a motorway route – seen together, this body of work seems to effectively convey the complexity of the current situation in Greece. Was this your intention?

Whether it was intentional or not, I cannot say for sure and would not feel confortable re-inventing an updated the narrative of the works. On the other hand, the way I can best describe the portfolios you mentioned (2000-2008) is as a meticulous and careful examination of “clouds gathering” before the storm. I admit that I never foresaw the crisis we currently experience, but I surely documented the signs of our society approaching a dead end.

Having documented so many different aspects, are you frustrated by how many news outlets depict the crisis, focusing on Greek “tragedy” and ruin-porn-esque views of empty Olympic sites, for example?

One could argue that an artist working in any discipline, let alone photography, always tries avoid a superficial representation of reality. In short, an artist seeks to bring depth to his or her work by avoiding the obvious. Sadly, it is this approach that we witness media across the world employing when trying to portray the current Greek crisis. From the point of view of the market, it is completely understandable, as this kind of image sells and is quite cheap to come by. The unfortunate effect of such editorial policies is that it tires the viewer quickly; after a while no one wants to see or hear anything coming from that part of the world. We gradually become insensitive to other peoples’ suffering, as if we are growing a thick skin to protect ourselves from the ugliness of the world. History has taught us that when we go down that path, nothing good can be expected in the near future.

Something of a counterpoint to this is your work shooting the Renzo Piano designed Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center in Athens– a project that is just nearing completion, not falling down. Can you tell us a little about your approach?

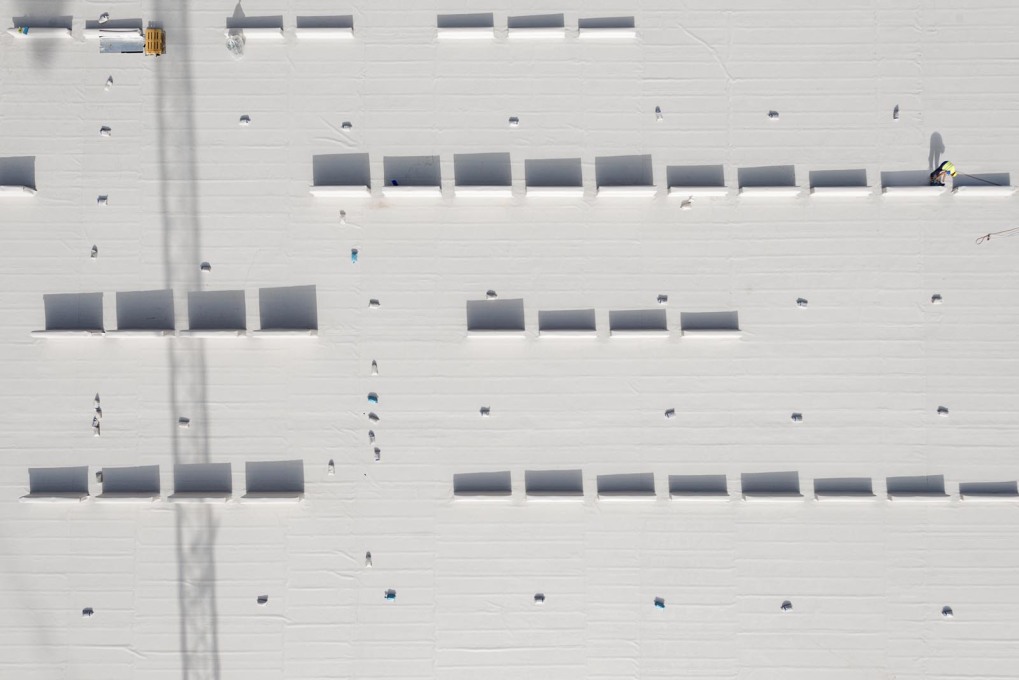

I was privileged enough to witness a landscape in transition. During the last nine years I have been (and will continue) following the project that includes the construction and complete outfitting of new facilities for the National Library of Greece and the Greek National Opera, as well as the creation of the 210,000 m² Stavros Niarchos Park. Over the course of years the project gradually revealed to me the very essence of what I do, which is best described using Robert Adams’ words: “What a landscape photographer traditionally tries to do is to show what is past, present and future at once,”.

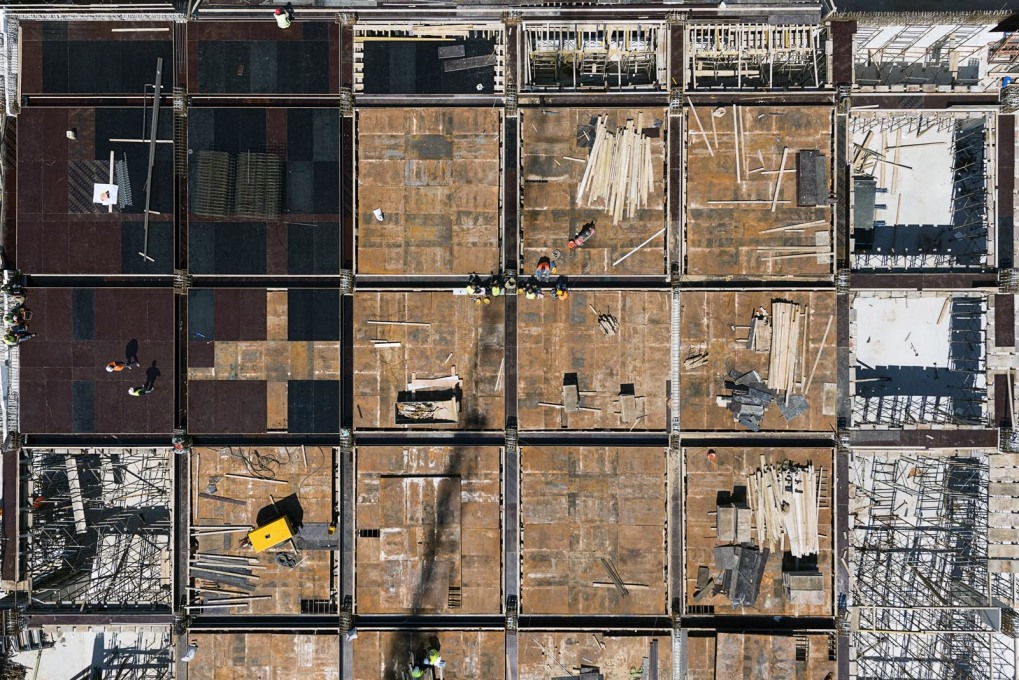

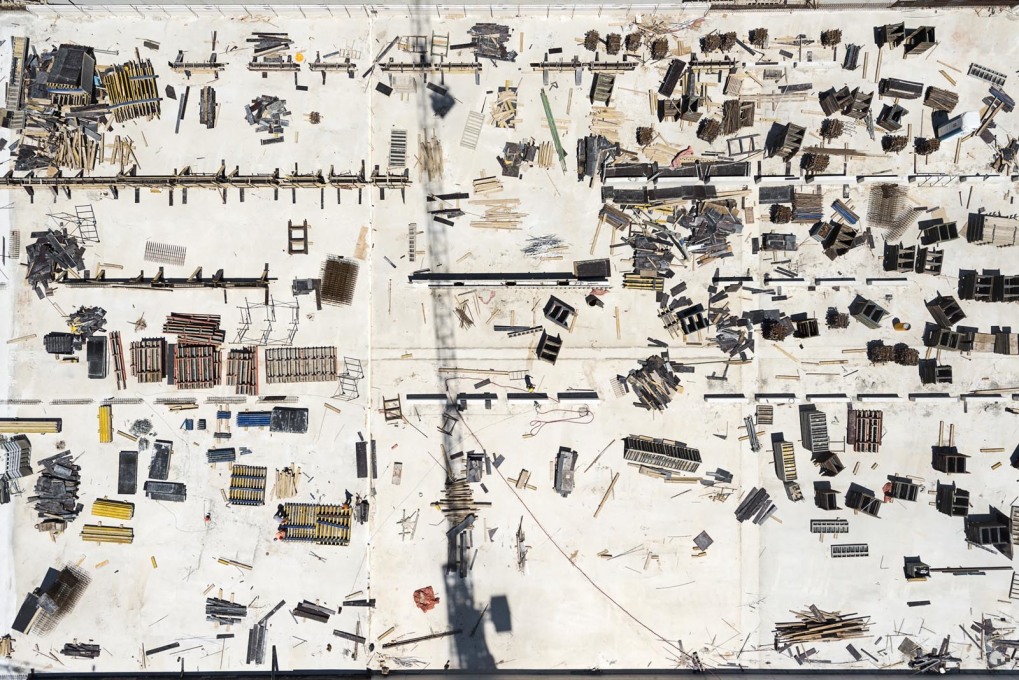

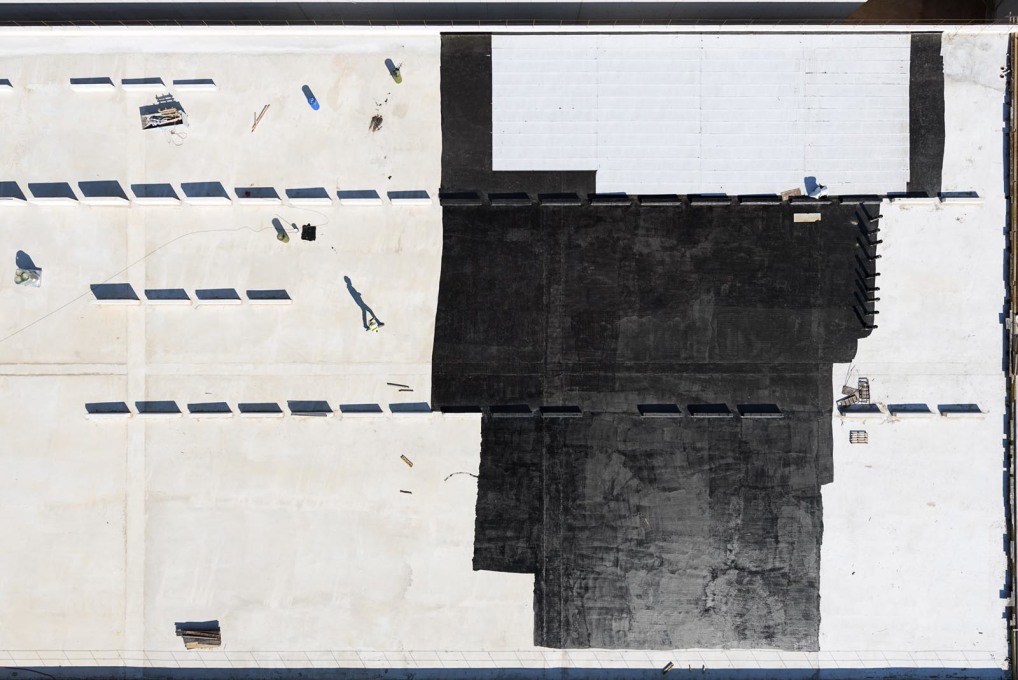

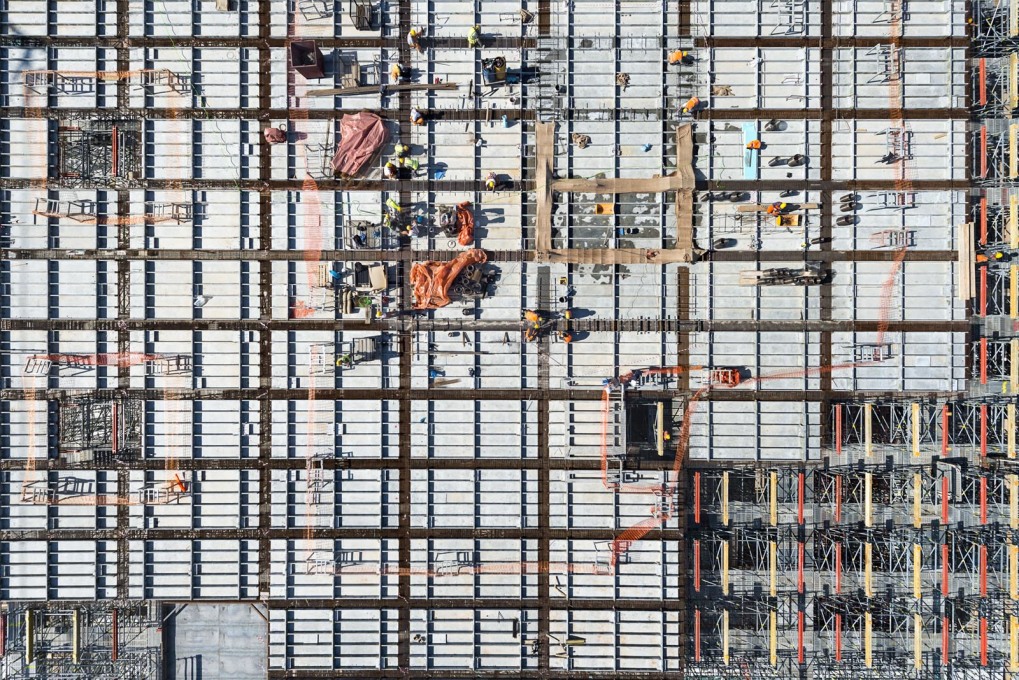

The transition of the landscape from an empty lot to the built complex has been photographed, layer-by-layer, as the building has slowly risen from the ground. The main idea behind the photographs is to show this process by recording the interim phases of the site during construction.

The vocabulary of architectural orthogonal drawings is borrowed by the photographic lens: elevations, sections and floor plans simultaneously document and interpret the daily progress of the construction, keeping track of the ephemeral forms that will disappear after a while, shaping the memories of the site and foretelling its future form. It remains a hope of mine that the construction photographs will preserve the traces of the major changes taking place in this landscape, before they are consigned to memory when the final result is permanent and loses its capability to surprise.

Where does your interest in “human-altered landscapes” stem from?. How do you find people change space, particularly that which is designed by architects?

As far as my photography is concerned, I am interested in representing human presence within a landscape that is apparent, yet discrete. People seen from a distance, with no apparent individuality; human figures that convey scale and populate space, but observed from afar.

Regarding how far people interact with and change space, it might come as a surprise but the question in Greece now is the complete opposite one: how can we explore the possibility that space designed by architects can change the way people perceive, understand and respect it. Unlike central Europe, in Greece seldom have we experienced public space designed by informed professionals. In a very old city like Athens, for example, architects are seldom involved in the designing of new public space. This is due to firstly, a lack of funding and secondly the complexity of the archaeology, which means that when findings are unearthed during construction, activity comes to a temporary stand still.

Public space is, therefore, left unattended. Perhaps people can learn lessons not only from from the recent failure of the Olympic sites, but also from the great success of two inspired operations that gave Athens the Cultural-Archaelogical Park (a 357-hectare, crescent-shaped zone encompassing the most prestigious archaeological sites) and Thessaloniki a 3.5-kilometre linear park by the sea front. Perhaps then there is hope that the people of Athens will welcome the new Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center and make it their own, changing the relation between public space and citizens; it’s a place dedicated to education, culture and the environment that belongs to our society – and not just to the state.

Interview by Fiona Shipwright

Yiorgis Yerolymbos was born in Paris, France in 1973 and studied photography in Athens and Paris and architecture in Thessaloniki. He holds an MA in Image and Communication from Goldsmiths College, University of London (1998) and a PhD in Art and Design from University of Derby (2007). He has presented five solo exhibitions and participated in numerous group shows in Greece and abroad.

Further reading: uncube issue no. 43 Athens