-

Magazine No. 11

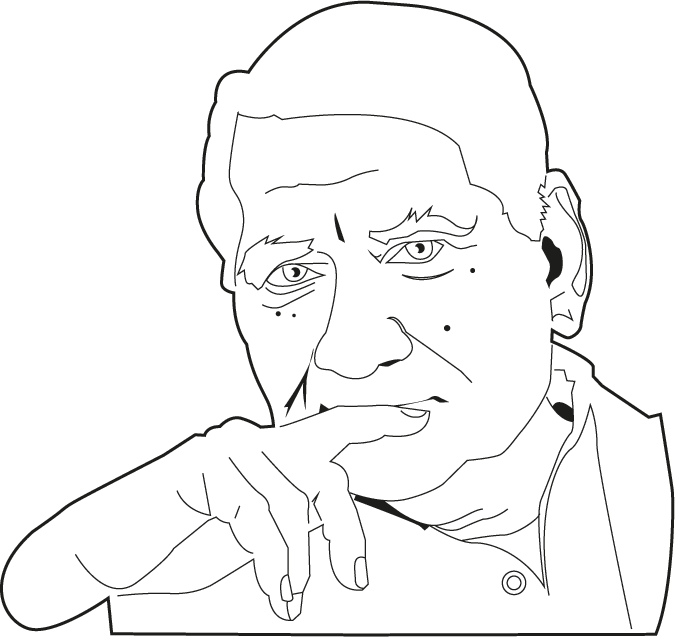

Charles Correa

-

No. 11 - Charles Correa

-

page 02

Cover

-

page 03

Editorial

Charles Correa

-

page 04 - 05

Introducing ...

Charles Correa

-

page 06 - 08

Kanchanjunga!

Correa's innovative “vertical bungalow” living

-

page 09 - 12

Hornby Trains, Chinese Gardens and Architecture

Charles Correa reflects on his (locomotive) origins as an architect

-

page 13 - 16

Then and Now

One of Correa’s first works - and one of his latest

-

page 17 - 26

A Usable Art

In conversation with Charles Correa

-

page 27 - 28

Economy Chic

An early model for climate-adapted mass housing

-

page 30 - 38

Mainland Shift

Charles Correa and the making of Navi Mumbai

-

page 39 - 45

Architectural Gifts

On the exhibition Charles Correa: "India’s Greatest Architect," and the arrival of the architect's archive in London

-

page 46

Klaustoon

VI. Metropol Para Poli

-

page 47

Next

Into the Desert...

-

-

uncube’s editors are Elvia Wilk, Florian Heilmeyer, Jessica Bridger, and Rob Wilson. uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online magazine covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

For this issue, we’re taking an in-depth look at the work of Charles Correa.

The Royal Institute of British Architecture in London is currently celebrating his work as “India’s Greatest Architect.” Marketing hyperbole perhaps — but there are certainly few architects to whom we would consider dedicating a whole issue.

Here you’ll find an interview with Correa in London, a review of the RIBA exhibition, and an in-depth look at not only his architectural projects but at another key aspect of his practice: urbanism. And, as always, some twists and turns along the way.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Cover image: Jawahar Kala Kendra. (Photo © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

-

Introducing...

Charles Correa

Charles Correa has gained an international reputation as an architect, planner and theorist through his influential body of work, one that has dealt so concretely with what remain the hot-button issues of today: climate, housing, city-planning, cultural context.

Born in 1930 in Secunderabad, India, he first studied at the University of Bombay, and then the University of Michigan (1949–53) and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1953–55), before returning to India in 1958 to set up his own architectural practice in Mumbai.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

Correa’s key built works in India include: Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalya Museum, Ahmedabad (1958-63), Tube House, Ahmedabad (1961-62), Hindustan Lever Pavilion, New Delhi (1961), Belapur Housing, Navi Mumbai (1970-83), Kanchanjunga Apartments, Mumbai, 1970-83), National Crafts Museum, New Delhi (1975-90), Jawahar Kala Kendra Cultural Centre, Jaipur (1986-92) and the British Council, Delhi (1987-92). In recent years he has also completed significant international projects, including the MIT Brain & Cognitive Sciences Complex in Boston (2000-05) and the Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown in Lisbon (2007-10).

Throughout his architectural practice, Correa has been heavily involved with theoretical and practical issues of the city, above all in the one where he lives: Mumbai. Between 1970-75, Correa was Chief Architect for New Bombay (now known as Navi Mumbai), and from 1974-78, Chairman of the Housing, Urbanisation & Ecological Board of the Bombay Metropolitan Authority. He founded the Urban Design Research Institute in 1984, and the following year Rajiv Gandhi appointed him Chair of the first National Commission on Urbanisation in India.

The sensibility and quality of the work of Charles Correa has won wide recognition – and a wide variety of awards including the Royal Gold Medal from the RIBA (1984), the Gold Medal from the Indian Institute of Architects (1987), the Praemium Imperiale in Japan (1994) and the Padma Vibhushan Civilian Award (2007).

2013 marks the year that Correa has gifted his extensive archive to the RIBA Library, subsequent to his having completely digitized it, making it freely available for study by students and others worldwide.

![]()

-

![]()

Kanchanjunga!

Correa’s innovative “vertical bungalow” living

One of Kanchanjunga’s double-height terrace gardens, semi-sheltered but scooping the breezes from the Indian Ocean. (Photo © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

-

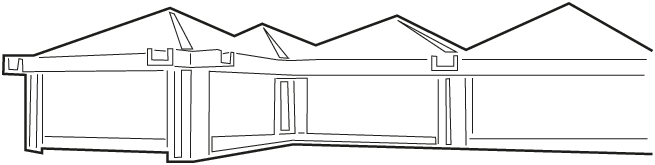

In Mumbai, buildings are ideally orientated east-west to catch the prevailing sea-breezes, and views out to the Arabian Sea on one side and the harbour on the other: the same directions as the hot afternoon sun and heavy monsoon rains. Bungalows traditionally solved this problem by wrapping a protective layer of roofed and shaded yet open veranda around the main living areas.

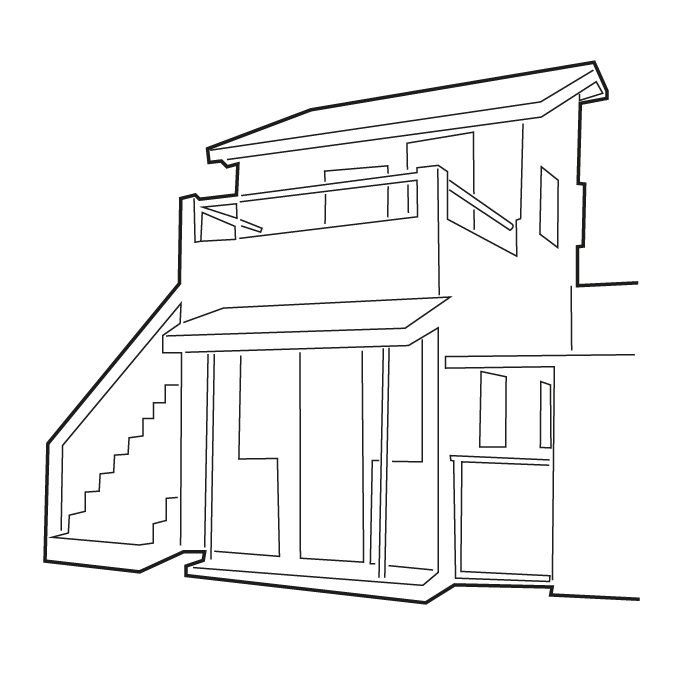

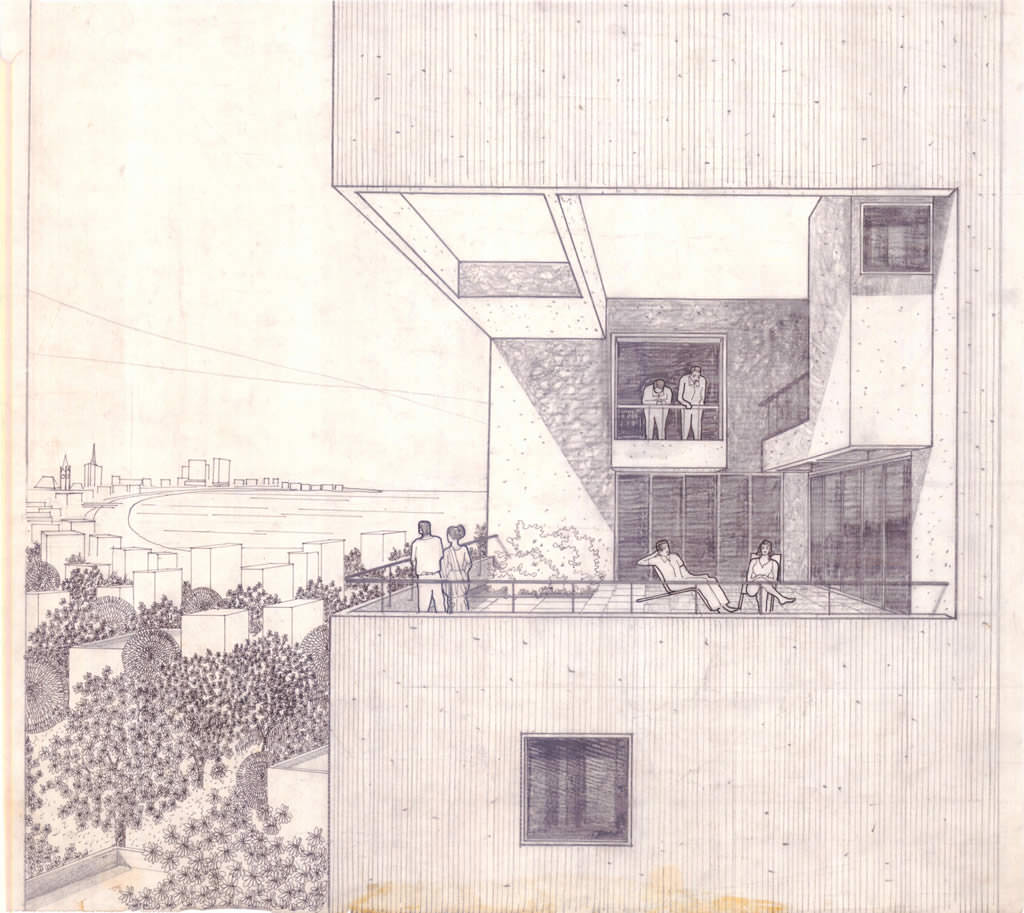

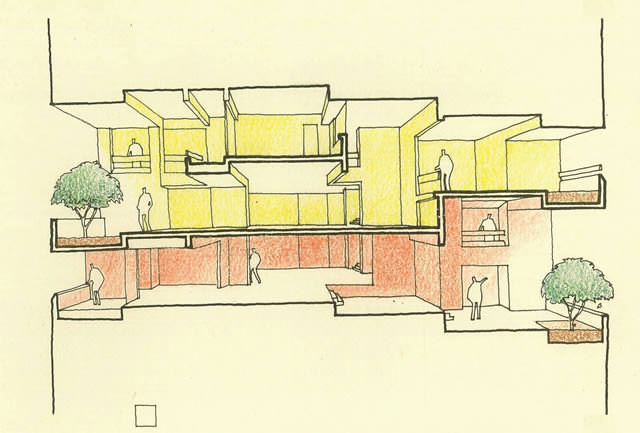

At Kanchanjunga (1970-83), an 84-metre-high condominium of 32 luxury apartments in Mumbai, Correa radically applied these principles to a high-rise building.

Four different types of apartments interlock across the width of the block, ending in double-height terraçe gardens at the corners that act like partly protected verandas, their internal spatial complexity expressed as semi-regular graphic cut-outs up the height of the block.

![]() (rgw)

(rgw)![]()

Kanchanjunga Apartments, Mumbai. (Images © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

![]()

Sketch section though block showing the interlocking of two apartments.

-

![]()

The Kanchanjunga Apartment complex in its urban Mumbai context. (Image © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

-

![]()

![]()

![Hornby Trains, Chinese Gardens and Architecture]()

Correa reflects on his (locomotive) origins as an architect

Text by Charles Correa

-

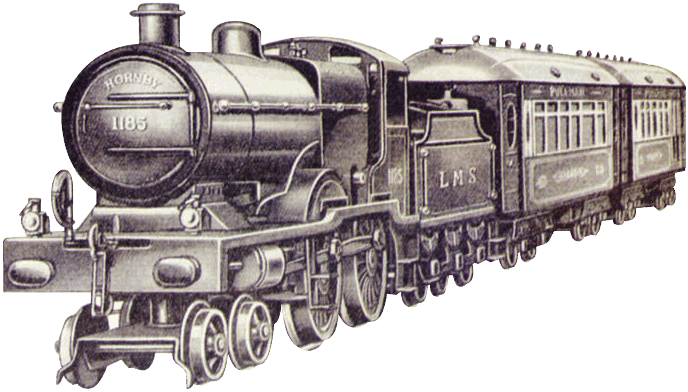

I think I became an architect because of toy trains. As a child, I had a Hornby tinplate track and a couple of locomotives and wagons. Nothing very ambitious, really just enough to run the trains around your room, and the following day, perhaps change the layout so that they could run into the next room, under a table and back again. That was the marvelous thing about those old tinplate rails. They had flexibility. Every time one finished playing, back they went into their wooden box – to be reincarnated the next day in a totally new formation.

Ah, to have more rails – and more trains! But since World War II was on, there was no way my layout could possibly have been augmented. All I did have was catalogues (the legendary Hornby Book of Trains, Basset-Lowke’s Model Railways and so forth), which I would pore over. I drew out on graph paper the most elaborate layouts: straight rails, curved ones, sidings, crossovers, the works. Trains moved through tunnels, stations, over-bridges in one direction and then, through cunningly placed figure eights, came right back through the same stations and tunnels – but now in the other direction, setting up a brand new sequence!

That’s how I spent many of my classroom hours: drawing up these hypothetical layouts in exercise books. Years later, at the age of fifteen or so, coming across an architectural journal for the first time, I felt I could read the various plans and sections—and what they were trying to do. That much I owe to Hornby.

![]()

Hornby train set. (Photo © Alamy, The Guardian)

![]()

Chinese garden. (Photo © Dr. Sun Yat-Sen)

-

Cut to many more years later. As a young architect, I’m perplexed by the contrary attitudes of two quite different thought processes. The first produces architecture which has very strong conceptual ideas – but on which you do not really linger beyond the first five minutes. An example might be Eero Saarinen’s three-pointed dome at MIT – a very elegant creation, but also perhaps something you might feel you have digested in one scanning. On the other hand, there is another kind of process, which does not involve any holistic schema at all. Many buildings (and most interiors) are designed this way. They present you with a series of spellbinding effects, one after another; perhaps without any real inter-relationship – except, of course, that one set-piece follows the previous one in a knockout sequence, rather like the way Gone With the Wind is structured around a series of unforgettable scenes. Or like the stories of Scheherazade. Once the sequence starts, you’re hooked – but can this ever provide a legitimate basis for serious architecture? Can such arbitrary and episodic narrativeever express the control, the rigor, and the discipline, so fundamental to holistic thought?

»Once the sequence starts, you’re hooked – but can this ever provide a legitimate basis for serious architecture?«

Jump cut again, to China. Before I visited my first Chinese garden, I was confused. Photographs showed only some fragile scenographic effects: the quirky little bridge, the dragon wall, the pond of water and so forth. Yet, when you actually get there and start walking through the garden, it gradually builds and builds until it finally overwhelms you. Hornby all over again! First you go through the sequence of pond and bridge and dragon wall in one direction, and then you find yourself coming in from another direction, experiencing them all in another sequence, in another order, from another height and so forth. The same handful of props are used and reused, again and again. And each time, because of a slight change in angle, or in sequence, they carry a new significance.

Restricting the number of elements, and using them over and over, is the key decision. It confers on the Chinese garden the rigor that the mandatory square piece of paper generates in Origami.

-

A Place in the Shade: The New Landscape and Other Essays

Charles Correa

Hatje Cantz (September 30, 2012)

English

Paperback, 6.7 x 0.8 x 9.4 inches, 246 pages

ISBN: 978-3775734011

![]()

Original poster for the Japanese movie “Rashomon,” 1950.

By making the number of set pieces finite, but the variations in your perception of them seemingly infinite, the garden becomes, at one and the same time, both holistic and episodic. Perhaps the repeated tales told in Rashomon (the bandit, the husband, the onlooker, the wife) also stem from this same paradigm. With each narration of the identical events, truth is reborn again in a new form, trans-forming the lyrical open-ended tales of Scheherazade into the refracted and imploded metaphysics of Kurosawa’s masterpiece.

That is what toy trains are really about—those wonderful tinplate rails that made patterns across the bedroom floor (the way the real thing makes pat- terns across a landscape, or across a nation), abstract patterns that recall in the mind’s eye the true reality of railway journeys. Today, these toys are no longer available. What killed them off? The banal quest for super-realistic ‘Scale Model’ railways and those stunningly prosaic attempts at so-called ‘realism’. Instead of the continuously changing patterns of demountable rails, we have today scale-track, nailed down permanently on to a baseboard – in the process fatally maiming that extraordinarily sophisticated level of abstraction and imagination that children brought to their tinplate layouts.

![]()

Essay taken from

A Place in the Shade -

![]()

Photo © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA

![]()

Photo © Charles Correa Associates

One of Correa’s first works –

and one of his latestTHEN & NOW

-

1958-63

Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya, Sabarmati Ashram, Ahmedabad

This memorial museum is sited at the Sabarmati Ashram, where Mahatma Gandhi resided from 1917 to 1930. Built in homage to Gandhi and intended to propagate his ideas, the museum houses letters, photographs, and other documents that trace the freedom movement that he launched. Whilst most of the materials used in the construction are similar to the other buildings in the ashram – tiled roofs, brick walls, stone floors and wooden doors – a clear exception are the large reinforced concrete channels, which distinctively cap the main structure, acting as both beams and rainfall conduits. These graphically mark the grid-like plan of the museum, one which allows for additional bays to be added in the future. No glass windows are used anywhere in the building, instead light and ventilation are modulated by adjustable wooden louvres.

Photos © Charles Correa Associates

-

2007-10

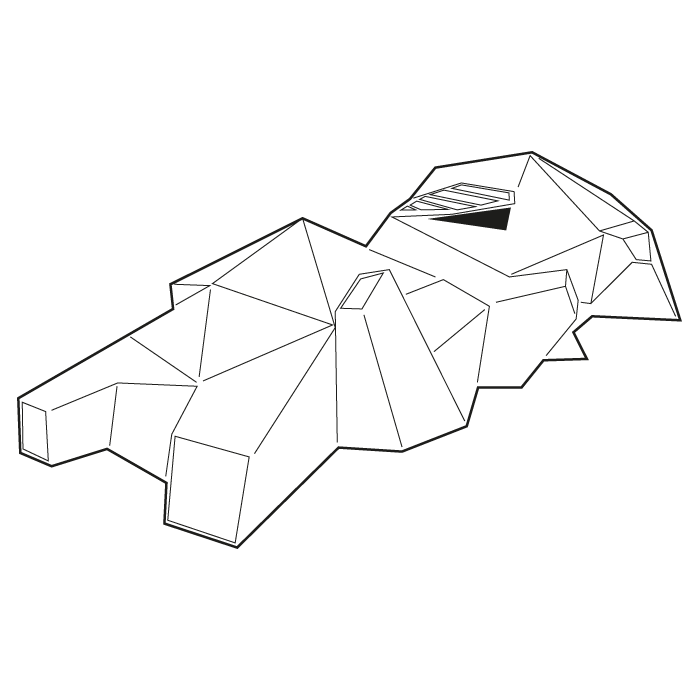

Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown, Lisbon, Portugal

When planning this new research centre for bio-medical science, Correa was inspired by the history of the site, where Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama set out on his 1497 voyage during which he reached India. Correa also drew on his experience of designing for a very different location – the MIT Brain & Cognitive Sciences Complex in Boston – by ensuring that a social space forms the centre of the complex: a large near-enclosed terraced garden, an “open-to-sky-space,” giving doctors and scientists a place to relax and reflect. Of the three units that constitute the project, the largest is for the research and patient rooms, the second contains the theatre, exhibition hall, and offices, and the third is an open-air amphitheatre for the city. They have been arranged to create a 125-metre-long pathway that leads diagonally across the site towards the open sea – and the horizon beyond.

![]() (rgw)

(rgw)Photo © Charles Correa Associates

-

A Usable Art

When Charles Correa was recently in London for the opening of his RIBA exhibition, Rob Wilson spoke with him about some of the key ideas, influences and recurrent themes in his work throughout his long career.

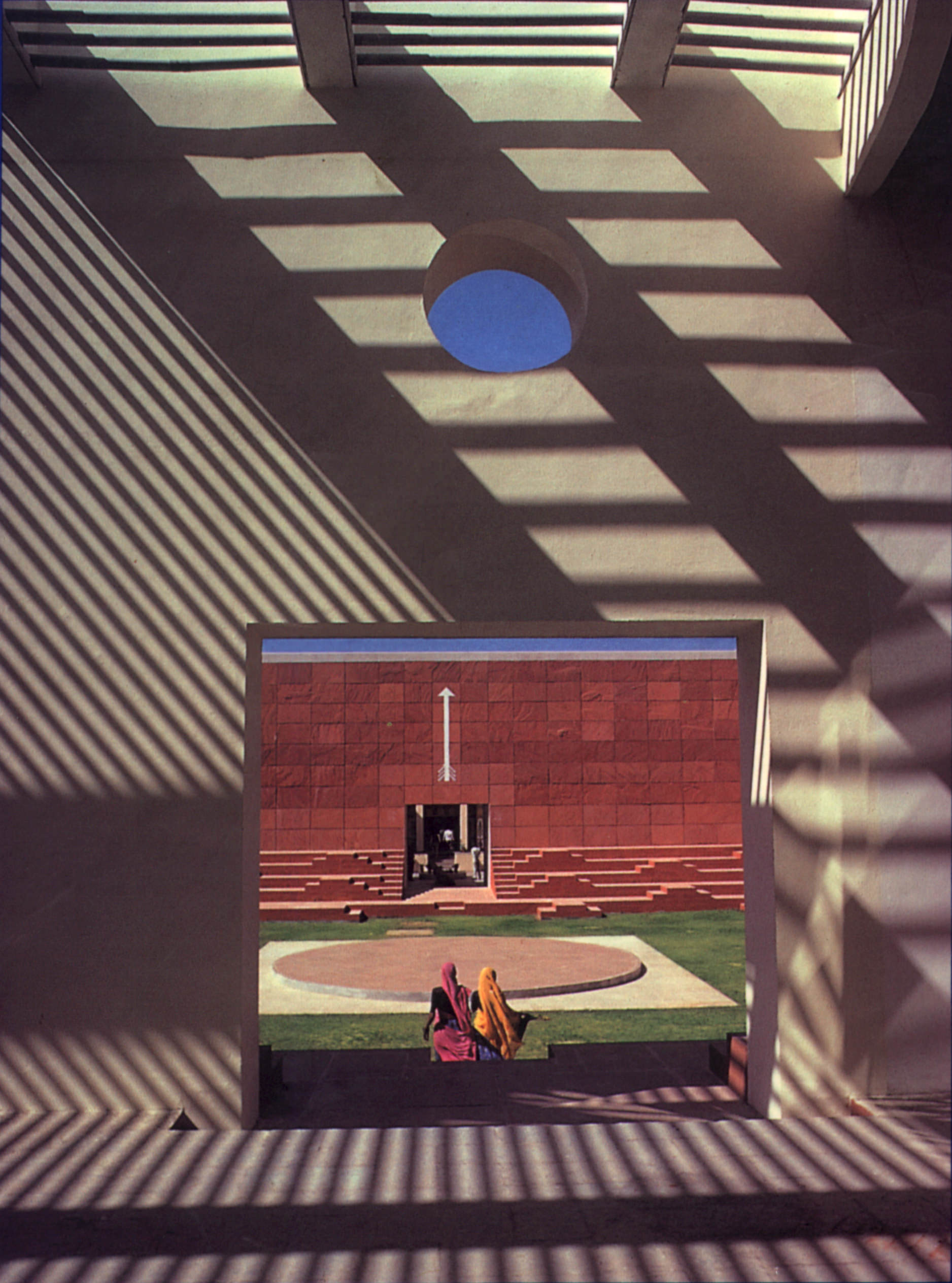

Interview by Rob Wilson

Jawahar Kala Kendra, Jaipur, 1986–1992. (Photo © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

-

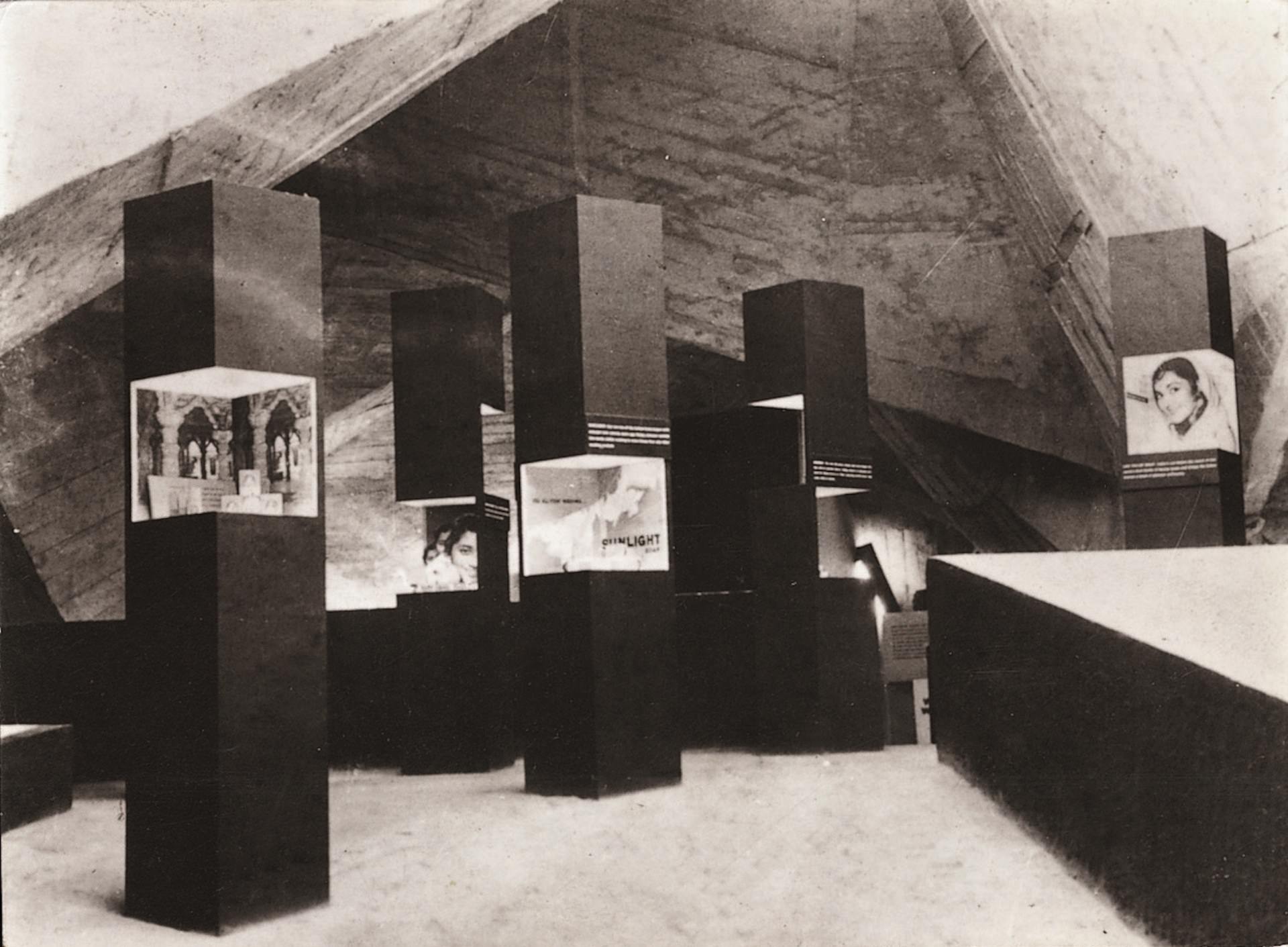

![]()

Hindustan Lever Pavilion, Delhi, 1961. (Photo © Charles Correa Associates)

Robert Wilson: Your work has been cited as being key in the development of Indian architecture over the last 50 years. You have described how the work of Le Corbusier gave you the freedom to invent architecture of the future. At the beginning of your career, were you hoping to invent a new architecture for post-independence India?

Charles Correa: Do you remember George Orwell’s fable Animal Farm? The farmer has this big house that intimidates all the animals – so they decide to revolt and burn his house down. But when he runs away, they are too excited and tired – and a few days later the pigs move into the house and start running the farm exactly as the farmer did. And if a cow or horse protests, the pigs just show them a picture of the farmer’s house to frighten them. In a sense, that’s what we are doing in India. In New Delhi, Edwin Lutyens was specifically commissioned to create an architecture that projected the imagery of a “superior civilization.” Today we’re using those very images to control our own people! And whenever our government needs a new building, the Public Works Department follows the “Lutyens style” – builds an extension of the “farmer’s house.” Surely after 60 years of independence, we should find our own way? That was Corbusier’s message. Whatever the drawbacks of Chandigarh – and there are many – it is not the “farmer’s House.” Corb showed us that we could open a door into another landscape of our own making.

This element of invention in architecture has been very much underplayed over the last few decades with all the talk of contextualism. Look at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie house in Chicago – in 1908, it was a fabulous invention, like a spaceship that had just landed!

-

![]()

![]()

Construction and completion of Hindustan Lever Pavilion, Delhi, 1961. (Photos © Charles Correa Associates)

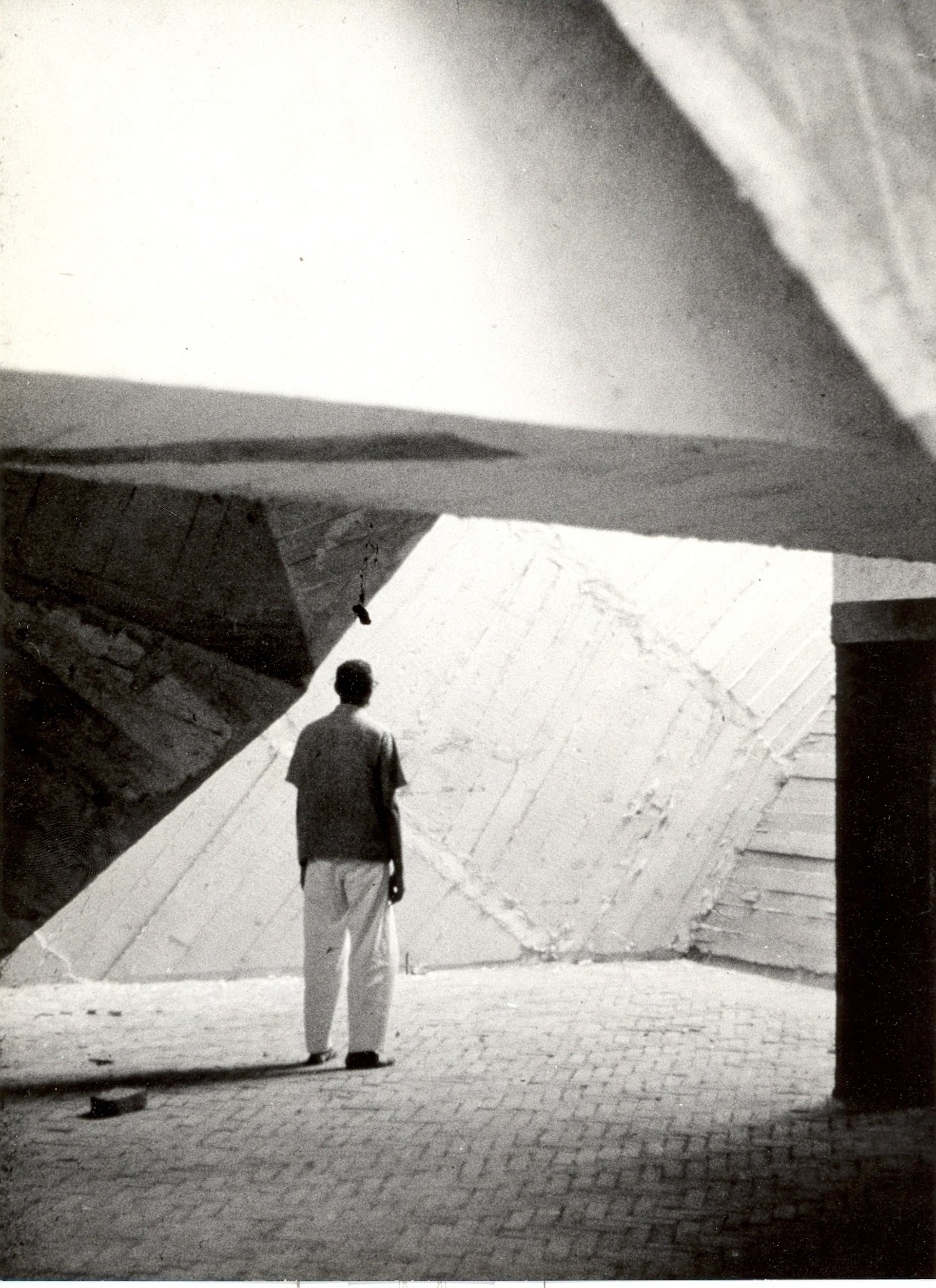

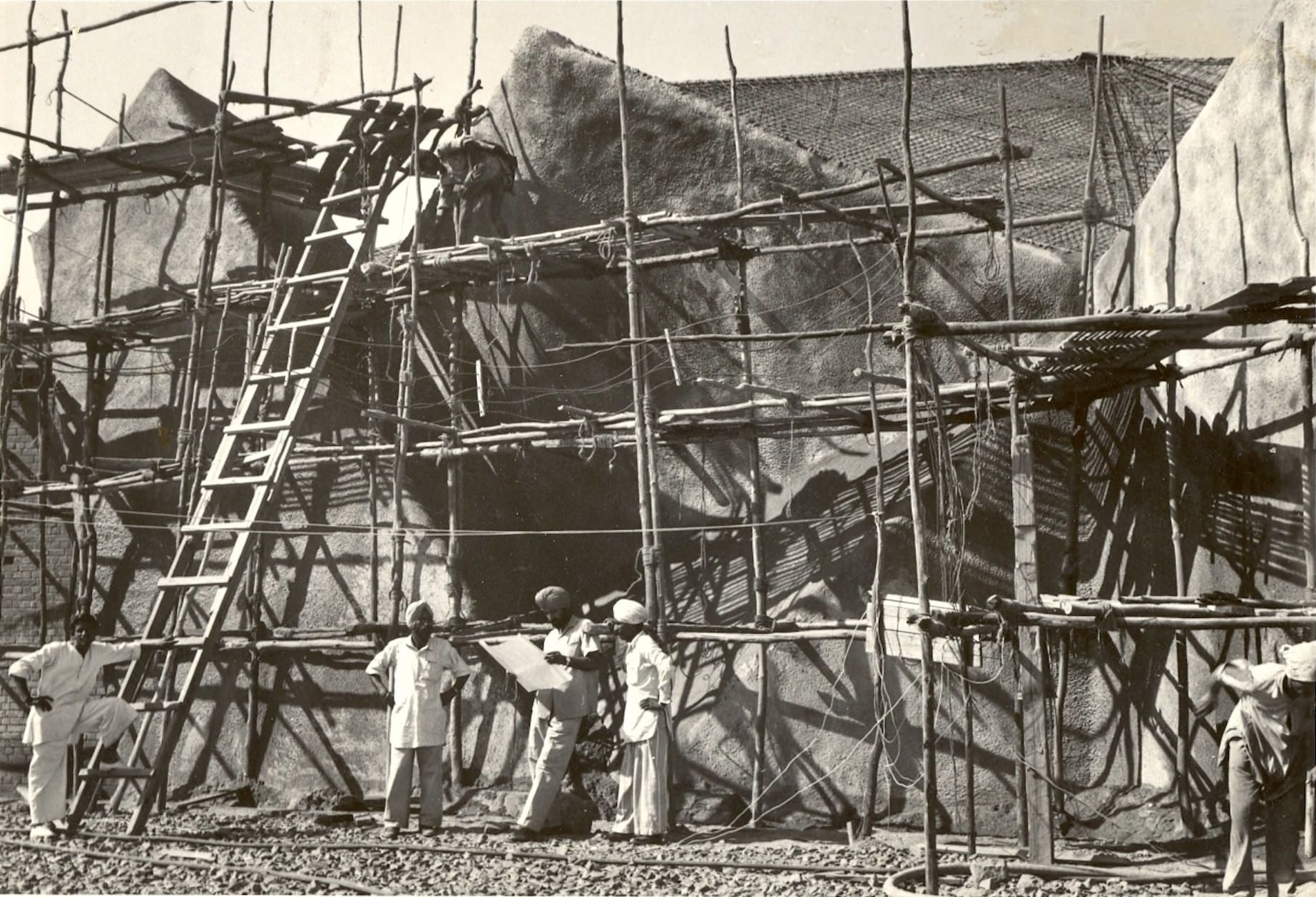

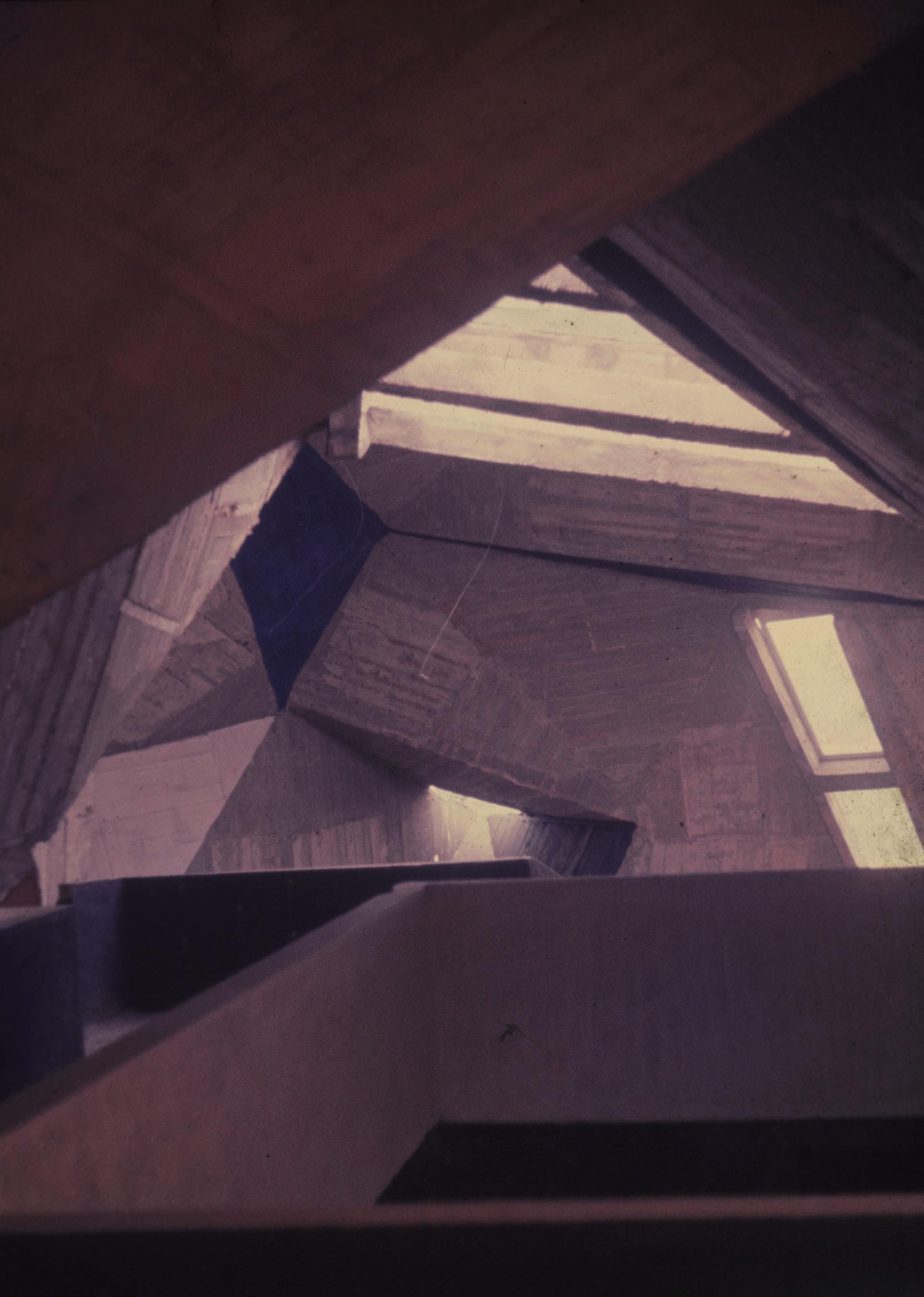

This sense of invention you mention can clearly be seen in an early project of yours, the Hindustan Lever Pavilion, where you seemed to be testing ideas and materials…

I wanted to see what happens when you break the orthogonal compass, the four directions that define our world: north, south east, west. Though the project was quite small, inside you lost all sense of orientation and scale – it could look immense or tiny. It was wonderful. But I wasn’t interested in investigating this further. How many times can you play that trick? One of the French Symbolist poets – was it Verlaine? – said the goal of art was to disorder the senses. I don’t agree. Mozart didn’t set out to break rules – but to perfect them.

One significant aspect of your work is its engagement with climate. You’ve said that “the wellspring of the imagination comes from the climate.”

It is wonderful how climate can generate architectural form. This is true of the igloo, it’s true of the Pacific islands. It’s true everywhere. You have to respect climate. You have to look at local materials, local technology, and then you can come up with elegant, surprising architecture.

You’ve been critical of Le Corbusier’s response to climate.

Well, Corb did respond to climate with his invention of brise-soleil. But unfortunately brise-soleil was more of a visual proposition for him. When you actually use those concrete louvres, you find firstly that they get full of pigeons – in India at least – and secondly, that they heat up during the day and then act like a radiator in the evening. It would have been better if instead of concrete, he had used a lighter material like wood, which cools much faster. Or smartest of all: build a verandah, which shades the main living area, provides circulation – and cools down right away.

-

![]()

![]()

Hindustan Lever Pavilion, Delhi, 1961

This extraordinary pavilion was designed by Charles Correa for one of the industrial fairs held annually in Delhi after independence. Its innovative concrete shell was shotcreted directly onto the steel reinforcement, configured intuitively by the great structural engineer Mahendra Raj. The result was an astonishing array of spaces in its interior, with ramps and platforms accentuating the fractured, scale-less sense of space for visitors. (Photos © Charles Correa Associates)»Corbusier was not religious, but he had a profound sense of the sacred, the metaphysical – otherwise how on earth could he ever have designed Ronchamp?«

-

The Tube House, a significant early housing project of yours, was shaped by its use of ventilation.

Yes. I love those wind-catcher houses found in Iran and Hyderabad, Sind. Those really are machines for living! In the most romantic sense: the way Le Corbusier meant it. He didn’t say “a machine for living, how prosaic” – but rather, “how romantic, how fantastic!” Like a ship is a machine for crossing the ocean.

You later applied this idea of housing shaped through its ventilation to a high-rise, the multi-storey Kanchanjunga apartments. Both these and the Tube House are now seen as ahead of their time. Did these set a model for other developments?

Not really. Back in the 1960s and 70s, when India was socialist, we didn’t have enough electricity for air conditioning – and that was a big challenge to the architect’s imagination. Today you not only have enough electricity, you have mechanical engineers who can solve any problem. So you don’t have to shape a building in response to climate: you can build a glass tower and just use low-e glazing. It’s so sad. It reduces the architect’s imagination to fashion.

Architecture is a three-legged stool: climate, technology and culture. Together they generate the building. This can be seen clearly in the Borobadur shrine in Java, which represents the seven levels of Nirvana. And in the great cathedrals of Europe expressing the Christian mind-set. So in my later work, like the Jawahar Kala Kendra cultural centre in Jaipur, the design has been shaped by climatic factors – like open-to-sky space and air ventilation – but it is also a metaphor for other values.

You’ve often stressed the importance of open space.

Open-to-sky space is very important in a warm climate. It has a practical aspect: in a one-room house for a poor family, a courtyard becomes an additional room. But there are metaphysical aspects as well. Open space means being in the open, like the guru sitting under a tree. It’s beyond education – it’s enlightenment. When you sit on the seashore, something happens to your mind.

Architecture has always had this mythical or metaphysical component. It’s extraordinary that since the beginning of time, man has used the most inert materials, like brick and stone, to express the invisibilia that move him. Corbusier was not religious, but he had a profound sense of the sacred, the metaphysical – otherwise how on earth could he ever have designed Ronchamp?

-

»Architecture is a usable art. It is sculpture – but sculpture usable by human beings«

Jawahar Kala Kendra. (Photo © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

Jawahar Kala Kendra, Jaipur, 1986–92

The city of Jaipur is astonishing for its synthesis of past and future, of material and metaphysical worlds. Maharaja Jai Singh, who built the fabled pink city, was moved by both the ancient mandala of nine planets (Avgraha) and contemporary ideals of science and progress. This arts centre, dedicated to India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, is likewise double-coded: a contemporary building based on an archaic notion of the cosmos. (Photos © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA) -

![]()

![]()

Jawahar Kala Kendra. (Photos © Charles Correa Associates)

You have often cited Corbusier as an influence, rather than Mies. Do you think Mies missed this mythical or spiritual side?

Mies just never taught me as much. If you look at his early work in Germany, there is a lovely sinister quality like in the old German movies, such as The Cabinet of Dr Caligari. The expressionism, the dark shadows. I think even the glass building he sketched back then was quite enigmatic. When he crossed over to the USA, he got lost in the banality of American downtown. The Lake Shore Drive apartments, they still had the old Miesian magic – which in the later work somehow got dissipated. He knew it too, I think.

Designing housing has always been important to you. Do you think designing housing helps ground a practice?

Yes, it’s sad how housing is now no longer part of an architect’s oeuvre, as it used to be, right up to Gropius, Mies, Corb, Wright, et al. Today housing is considered very downmarket: if you are really successful you should be designing only museums and airports! That is ridiculous.

In an architectural practice, there are always many different projects running simultaneously – even in a small office like mine, where typically we’ve had about 10 or 12 architects, we always had 5 or 6 projects. This allows cross-fertilization between projects, large and small – which is very important. Something you have learnt working on a small house becomes relevant in a large planning project at quite another scale. And vice versa. Having even one housing project in an office encourages this crucial process of cross-fertilization. Architects must break the habit of looking down at housing, as something that mainly concerns developers. Nonsense. Housing is far too important to be just left to market forces.

-

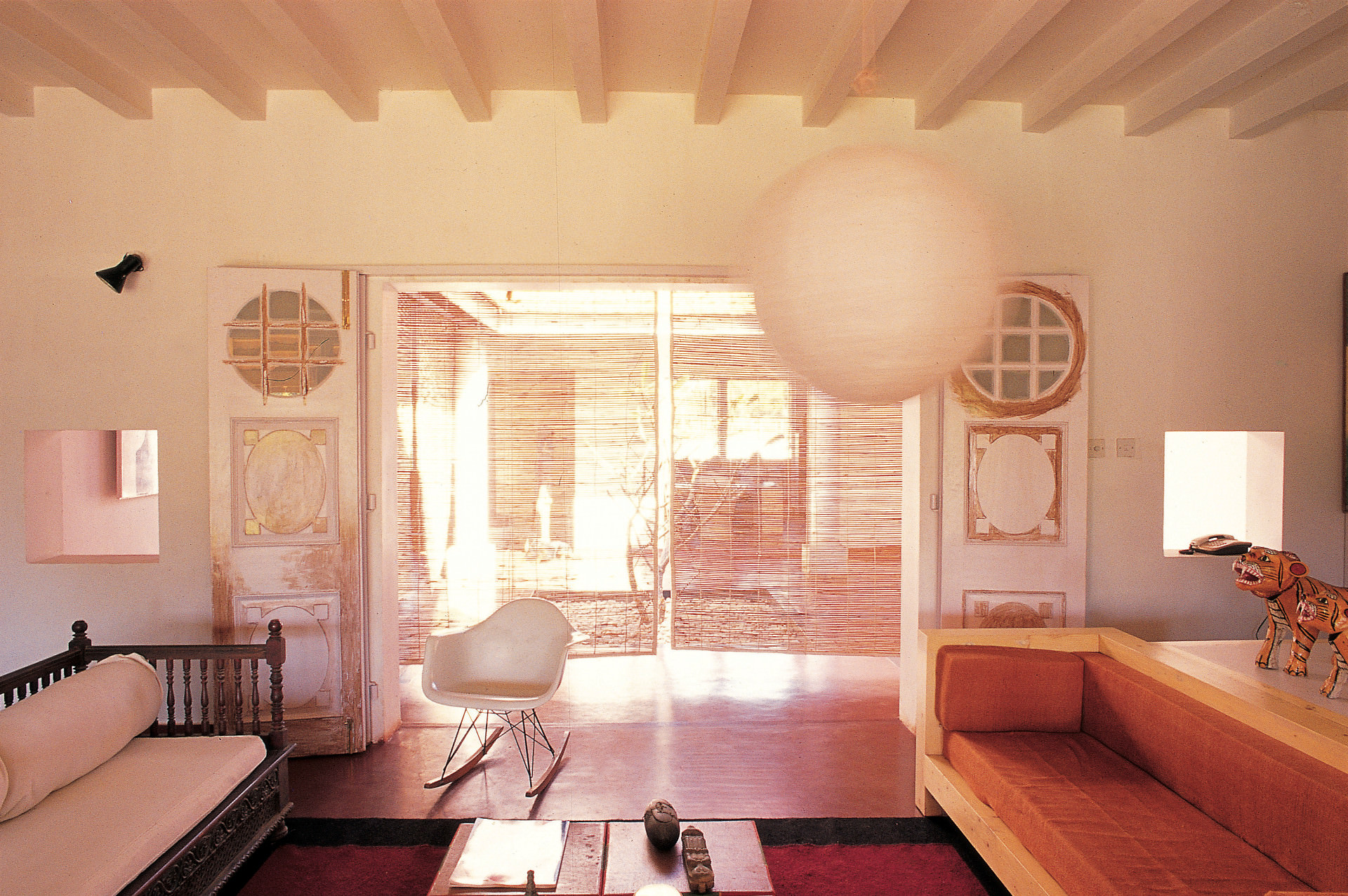

![]()

![]()

House at Koramangala, Bangalore, 1985-88

This house and studio were inspired by traditional Hindu houses in Tamil Nadu and Goa, which are usually organised around a small central courtyard, with a tree or tuisi plant in the middle. Here, the front door was intentionally placed off centre on the entrance façade, leading one along a shifting axis to arrive at the main courtyard – which acts as the central focus, whilst dividing the house from the studio, and providing light and ventilation to the rooms that surround it. (Photos © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

-

You’ve talked of architecture as sculpture. It is quite unfashionable to talk about architecture as an art today.

Architecture is a usable art. It is sculpture – but sculpture usable by human beings – with doors and windows, openings for light and air. And these openings do not diminish the qualities of the sculpture – on the contrary, they complete it. In short: architecture is sculpture with the gestures of human occupation. But perhaps it is precisely this usability that makes it so unfashionable. Henry Moore was a great sculptor who didn’t make anything functional. However Isamu Noguchi, who was also a great sculptor, designed useful objects like tables – and in the modern western context that diminishes his artistic importance. Isn’t that extraordinary? Have we forgotten that one of the greatest Renaissance artists, Benvenuto Cellini, was primarily a craftsman? Thank God in India the word for artist and the word for craftsman is the same.

In your practice you’ve always had a strong engagement with the city as a whole.

I think that is true of many architects. You can’t help getting involved with urban issues – especially in India, where they are so epic. So you just can’t just go on doing your mad jeweller’s act in one corner of the city – you are bound to see what else is going on around you. Working in India has a lot of frustrations, but the chance to address larger and more fundamental issues is one of its greatest opportunities.

![]()

![]()

Brain and Cognitive Sciences Complex, MIT Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000-05

This building’s site, in the Kendall Square area of MIT campus, straddles two pieces of land separated by a railroad track. The complicated location is matched by the building’s complex programming demands: it houses three major research institutes with separate identities and entrances. Yet inside the complex all three are melded together within the 450,000-square-foot facility, the largest of its kind in the world. (Photo © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA) -

ECO

NOMY

CHICAn early model for climate-adapted mass housing

-

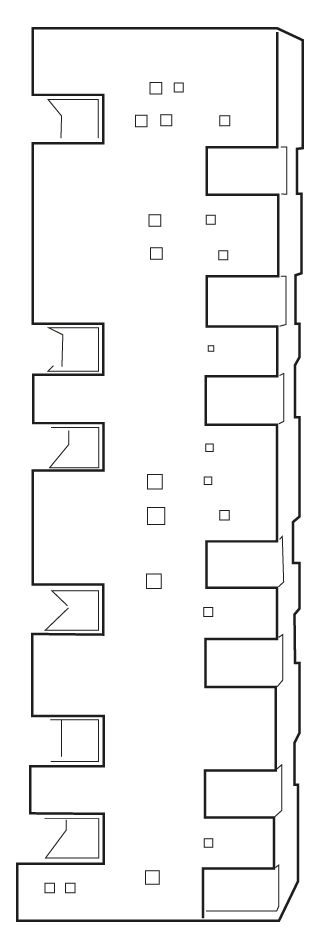

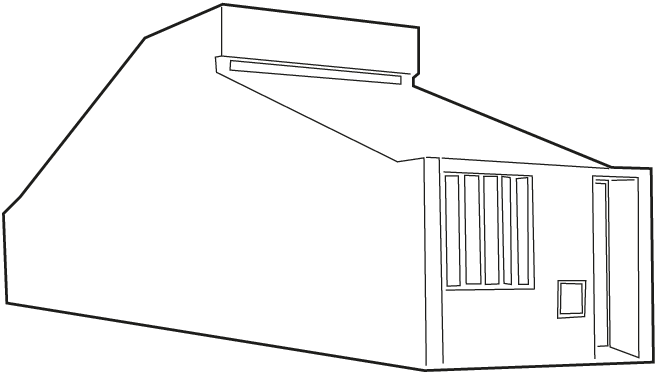

This 1962 design for the Tube House was one of Charles Correa’s cleverest yet simplest designs, one also way ahead of its time.

Its simple rectangular footprint provided an economical model for mass single-family housing, with blank sides designed to enable each unit to be combined in a variety of terraçed or clustered formats. However, its more complex section, rising at the centre to a double height apex over a mezzanine level, was modeled to cleverly funnel air, and thus ventilation, through, the house, with heat able to escape out of a sheltered internal court, open to the sky.

The design, adapted to economical construction and the extreme heat and monsoon rains of the regional climate, won first prize in an all-India competition for low-cost housing, yet only a single prototype was ever built, demolished in 1995.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Tube House, Ahmedabad, 1961-62. The building exterior has blank flanking walls, allowing for its mass-multipliaction and attachment in terraced or staggered formations. The interior has profusion of deep louvres and grilles, shading direct sun from the interior but maximizing air-flow and ventilation. (Photos © Charles Correa Associates, Courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA.)

-

![]()

Mainland shift

Charles Correa and the Making of Navi Mumbai

In 1964, Charles Correa, Pravina Mehta, and Shirish Patel proposed a radical re-structuring of Bombay – a city whose infrastructure was collapsing under the weight of an exploding population. Their design was no small invention, and today it’s recognized as a true feat of big-scale urban planning.

Text by Julian JainPanoramic view over the lake to Nerul, Navi Mumbai. (Photo: Julian Jain)

-

![]()

View of the hills around Matheran, Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR). (Photo: Julian Jain)

In geographical terms, the city of Mumbai is that rarest of places: a city far out at sea, emerging like a mirage above the waves. It floats on a narrow tongue of land, surrounded by water not on one or two, but three sides. The sea defines Mumbai, perhaps like no other city in India or indeed in the world. Throughout the city’s history, the sea has shaped Mumbai, encompassing its economic basis as a port and centre of maritime trade, its skills and employment, its settlement and mobility patterns, as well as its relations with the neighbouring mainland and other regional inland locations.

Originally situated on a handful of small islands around fifteen kilometres from the nearest mainland shore, in the late eighteenth century the city was joined by land reclamation to the larger Salsette Island in the north by the British. Mumbai, then called Bombay, spread from its colonial centre in the south towards the north in several developmental waves. The city’s original centre included its port, fort, docks, merchandise warehouses and subsequent business districts, neighbouring cotton mills, a railway terminus and other public institutions, most of which were built in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

-

The practice of simply extending the city’s boundaries further north while retaining the high concentration of jobs on the reclaimed southern promontory was more or less successful for much of the eighteenth to mid-twentieth centuries. However, by the early 1960s things were reaching a critical pitch. Bombay’s population growth was exploding, driving up prime real estate prices in the south and threatening to push much of the city’s poorer and lower-middle class population – the backbone of the city’s workforce and wealth generation – out into ever more distant suburbs in the north. The city was quickly turning into an urban “sprawl machine” attracting more and more migrants. This led to the rapid growth of the informal sector and formation of slums in inner-city locations, as many workers preferred to live in inner-city slums rather than in proper accommodation in far-away suburbs. At the same time, the two main north-south commuter train lines were becoming dangerously congested. The city was becoming the most densely inhabited place on the planet with some of the lowest open spaces per capita.

![]()

![]()

With extensive harbouring for ships and a local train network to ferry around both the population and the goods to service it, Navi Mumbai is well connected into the wider city of Mumbai and beyond. (Photos: Julian Jain)

-

![]()

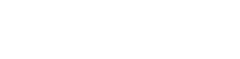

Development plans for Navi Mumbai from the Charles Correa archive. (Images © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

![]()

![]()

Bombay’s population jumped from 1.5 million in the years leading up to the Second World War to 4.5 million in 1964, and was predicted to double by 1984. By 1965, municipal limits had already reached the northern end of Salsette Island – today’s suburb of Mira Bhayandar – meaning that the city sprawled over a continuous 45-kilometre stretch from the south to the north. The very advantages that the sea and land reclamation had offered Bombay were rapidly turning into an unmanageable burden. There seemed to be no practical conception of how to deal with this self-perpetuating “one-way street” of urban development, had it not been for the vision of Charles Correa.

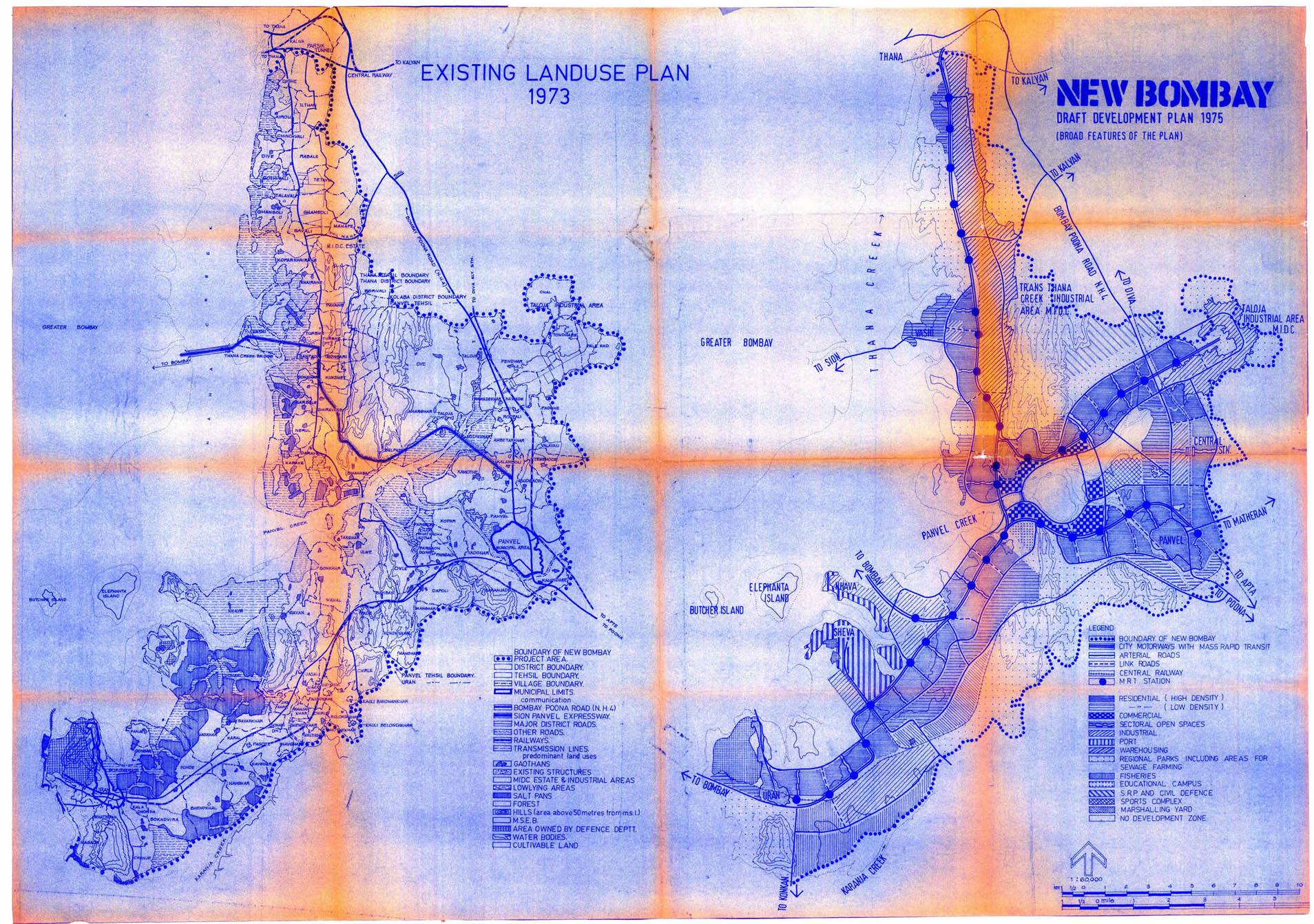

Along with two of his colleagues, Pravina Mehta and Shirish Patel, Correa submitted a memorandum to the Bombay Municipality in 1964, suggesting to re-structure the north-south developmental pattern into an east-west one centred around Bombay Harbour. The proposal would also integrate the areas on the mainland rim, some 20 kilometres east of the old centre of Bombay, into a new polycentric urban structure.

This was innovative thinking. It opened up entirely new perspectives on the future development of Bombay and its hinterland, and represented the first concerted effort at decentralising the urban functions of Bombay. Following much public support and extensive deliberation, the basic proposals were accepted by the state government in 1970. A new city was to be planned, called New Bombay, which would eventually become the largest planned city of the twentieth century.

-

Incremental Housing, Belapur, New Bombay/Navi Mumbai, 1983-86

This development is located on six hectares of land around two kilometres from the city centre. Consisting of seven houses grouped around a shared courtyard, each of which has its own piece of land, the complex is home to an entire social spectrum – from former squatter families to those in the upper income brackets – yet the sites vary little in size, each between 45 and 70 square meters. The houses’ simple floorplans can be incrementally expanded by local masons and craftsmen – thus generating employment in the urban economy exactly where it’s needed. This is an example of one of Correa’s innovative housing solutions for the region, that also with adaption could have a much wider application as an idea. (Photos © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

![]()

-

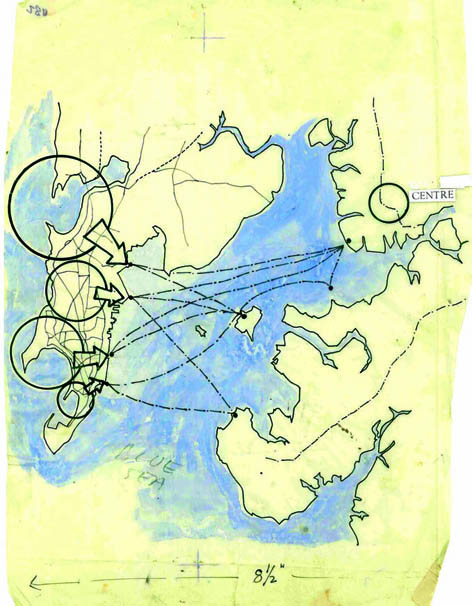

A specially-created state agency, the City and Industrial Development Corporation of Maharashtra, or CIDCO, was tasked with designing and developing the new city. Charles Correa was appointed Chief Architect to CIDCO from 1970 to 1974. While the old Bombay and its burgeoning suburbs were threatening to sink like a ship under its own developmental weight, an anchor onto the mainland had been thrown.

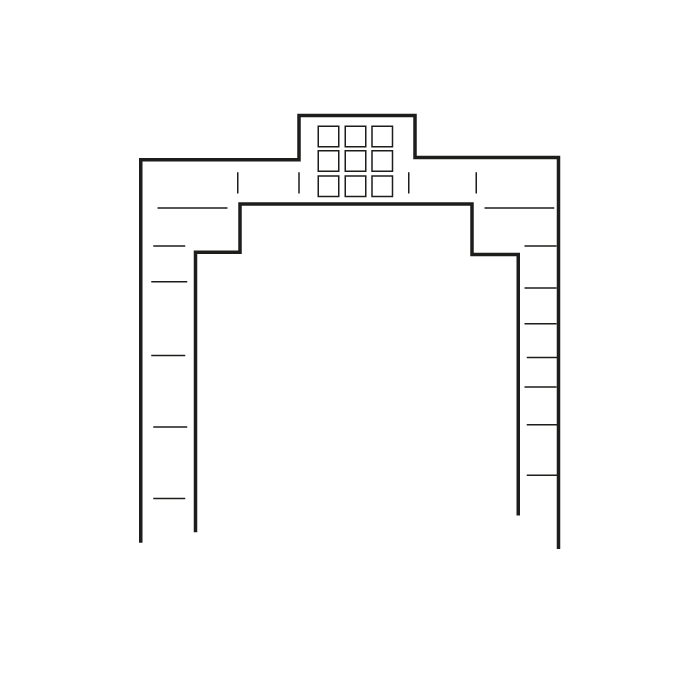

The city plan that Charles Correa envisioned was intended to diversify and decentralise growth and employment around Bombay Harbour, and to ease the burden on a city that was becoming increasingly congested. New Bombay was planned for two million inhabitants. The city was structured around two arms along the eastern rim of Bombay Harbour and Thane Creek, meeting in the middle at the site of an envisaged new city centre around Waghavali Lake. Each arm was planned around several developmental nodes, from Airoli in the north to Uran in the southwest.

The innovative quality of New Bombay’s planning was underpinned by a focus on public transport, low-income housing, rainwater harvesting, and responsive urban form typologies, including high-density, low-rise typologies. Originally planned as a “twin city” to Bombay, New Bombay, now called Navi Mumbai, has the potential to become a locus in a network of other cities and towns within the wider Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) that includes around 21 urban centres and 1,090 villages on an area of 4,355 square kilometres, with a total metropolitan population of around 21.9 million.

![]()

![]()

New constructions in Belapur, Navi Mumbai. (Photos: Julian Jain)

-

»The innovative quality of New Bombay’s planning was underpinned by a focus on public transport, provision of low-income housing, and development of responsive urban form typologies.«

View to recent constructions, showing the lush coastal environs of Navi Mumbai. (Photo © Julian Jain)

-

![]()

![]()

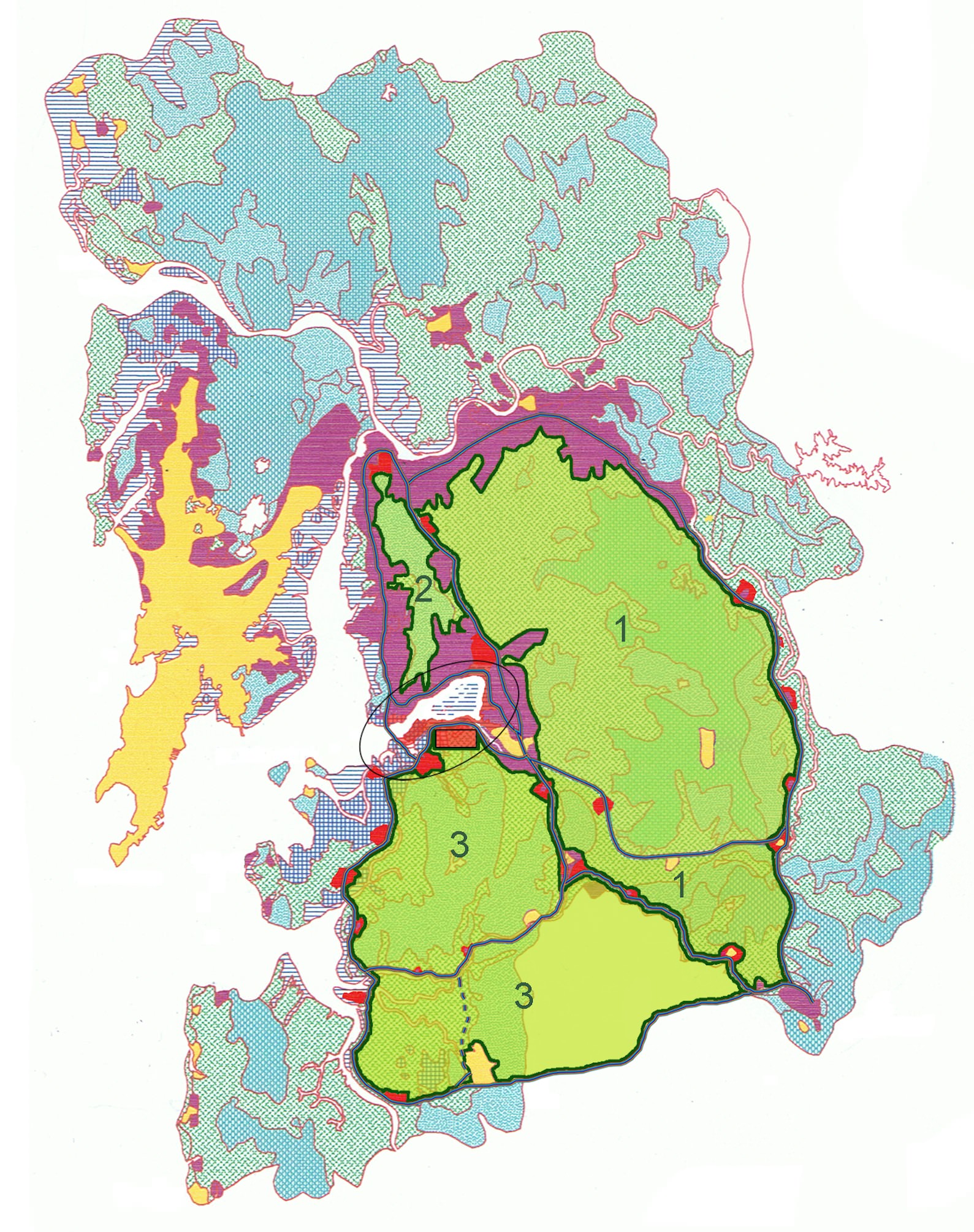

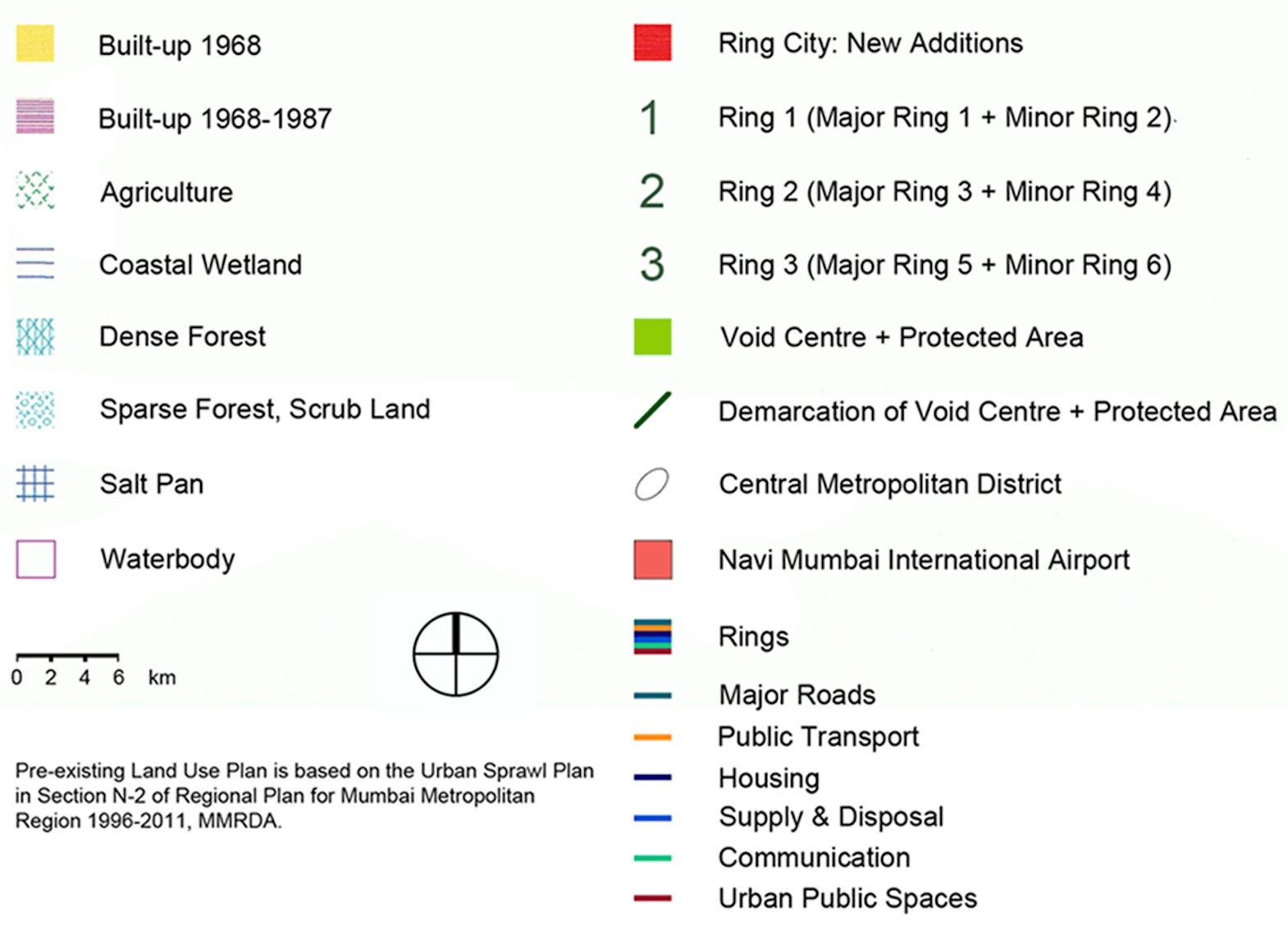

Photo from the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) of boats at low-tide, in an area which has been subject to a rethinking of land-use patterns and change. A recent land-use proposal for the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) re-imagining it as a series of three “void centres” with corresponding “ring cities,” based on proposals by Julian Jain, Berlin, and von Gerkan, Marg and Partners (gmp), Hamburg, 2009. The underlying land-use plan here is based on the Urban Sprawl Plan, part of the Regional Plan for Mumbai Metropolitan Region 1996-2011, Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA), Navi Mumbai. (Photo and graphic: Julian Jain)

![]()

-

Julian Jain is an architect and urban geographer. His research focuses on megacities and metropolitan regions of the South, and sustainable urban and regional development. His most recent publications include “Region of the Rings, Cities of the Void” in DOMUS India, vol. 1, issue 10, Mumbai, September 2012, and “Mumbai, the megacity and the global city: A view of the spatial dimension of urban resilience” in Institutional and Social Innovation for Sustainable Urban Development, Routledge (Earthscan), Abingdon, 2013.

Sources for this article include:

• Charles Correa, Housing and Urbanisation, Urban Development Research Institute (UDRI), Mumbai, 1999.

• City and Industrial Development Corporation of Maharashtra Ltd. (CIDCO), 2005 Survey, CIDCO, Navi Mumbai, 2005.

• Julian Jain, “Region of the Rings, Cities of the Void” in: DOMUS India, vol. 1, issue 10, Mumbai, September 2012.

• Julian Jain, Fritz-Julius Grafe, Harald A. Mieg, “Mumbai, the megacity and the global city: A view of the spatial dimension of urban resilience” in: Institutional and Social Innovation for Sustainable Urban Development, Routledge (Earthscan), Abingdon, 2013.

• Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA), Regional Plan for Mumbai Metropolitan Region 1996-2011, MMRDA, Mumbai, 1999.

• Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation (NMMC), About Navi Mumbai. (accessed 23rd April 2012).

• Population Census of India 2011, Provisional Population Totals. (accessed 14th May 2012).

• Sonja Ernst, Dossier Megastädte: Mumbai – Aufstieg zur Weltklasse, Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (BPB), Bonn, 2006.

In creating Navi Mumbai, Charles Correa expressed in urban planning and form the themes he also cherished and reflected in his architecture: incremental growth possibilities; symbiotically linked and open-to-sky spaces; high-density, low-rise typologies; a focus on the pedestrian and public transport; and the generation of local skills and the use of local building materials.

Navi Mumbai has grown considerably since its beginnings in the early 1970s. Around 30 percent of its households have relocated there from southern Mumbai, underlining its growing attractiveness as a place to live and work. Though it took several decades for growth to set in, owing in part to the continuing functional primacy of Mumbai and the initial dearth of civic institutions in Navi Mumbai, the city today offers some of the highest living standards of any new town development in the country, with excellent housing, education, healthcare, and sports facilities, and a relatively dense public transport network. It has developed its own profile and mostly functions independently of Mumbai, buoyed by its own economic development. In effect, it cannot be considered a suburb of Mumbai; most people who work in Navi Mumbai today also live there.

Navi Mumbai’s population, approximately 1.1 million in 2011, continues to grow. Recent developments include a new container-shipping port at Nhava in Navi Mumbai, the largest in India, a new information technology “knowledge corridor” passing through Navi Mumbai along the Mumbai-Pune highway, a new special economic zone (SEZ), and a new international airport just south of Navi Mumbai’s city centre, to be opened by around 2015.

Navi Mumbai and Charles Correa’s vision behind it mark the beginnings of innovative, viable post-independence urban planning in India and stand as an inspiration to further endeavours in the field of sustainable urban and regional development, both in the wider Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) and other parts of India – as well as in the global South at large.

![]()

-

Architectural

Gifts

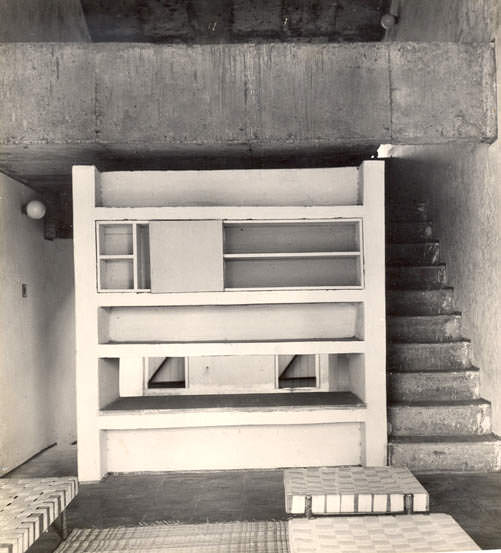

On the exhibition Charles Correa: India’s Greatest Architect, and the arrival of the architect's archive in London

Text by Vicky Richardson

Timber model of the Hindustan Lever Pavilion, part of Charles Correa's archive that has been gifted to the RIBA in London. (Photo: Wilson Yao, courtesy RIBA)

-

![]() Installation shot of the exhibition “Charles Correa - India's Greatest Architect.” In the background, the two-metre-high timber model of the Kanchanjunga Apartments in Mumbai. (Photo: Wilson Yao, courtesy RIBA)

Installation shot of the exhibition “Charles Correa - India's Greatest Architect.” In the background, the two-metre-high timber model of the Kanchanjunga Apartments in Mumbai. (Photo: Wilson Yao, courtesy RIBA)The retrospective of Indian architect Charles Correa currently at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), set to tour internationally, draws on the architect’s extensive archive, which he recently gave to the British Architectural Library, documenting Correa’s career over 65 years. Earlier this year the collection of 6,000 drawings, documents, photographs and models arrived in London, where it will be cared for by the RIBA. The exhibition shows reproductions of drawings, photography and some magnificent models. Ironically, original drawings are not able to be included as, until the RIBA’s new gallery is complete at 66 Portland Place, the Institute does not have the controlled conditions required to display them.

The gift is the most substantial ever received by the Institute from a non-British architect. For Correa the decision to send his archive overseas must have been an extremely difficult one. “India’s greatest architect” – to quote the subtitle for the exhibition – has devoted his career to India, and has contributed beyond measure to the design of its housing, important public buildings, and cities. -

»Correa’s principles are universal yet highly rooted in site.«

Most importantly, Correa has been engaged in a constant effort to define an alternative path for post-colonial and contemporary Indian architecture. There is no little irony that an architect whose work is so strongly rooted in a place should send his archive to London, a city that these days is a hub for a type of global architecture – an anathema to Correa’s work. But at the RIBA it will be well cared for, and most importantly for Correa, it will be accessible to students and architects from around the world.

The exhibition focuses on a selection of projects from more than 115 documented in the Correa archive, as well as expressing some of the architect’s important guiding principles. Correa’s work strikes a delicate balance between responding to the specifics of site – “representing the truth of the place” as he puts it – and certain firm principles, such as “the empty centre” and the ritualistic pathway. The latter is a device regularly employed by Correa to create a sequence of different atmospheres and ideas within a single building, providing a narrative about the diverse influences on Indian architecture.

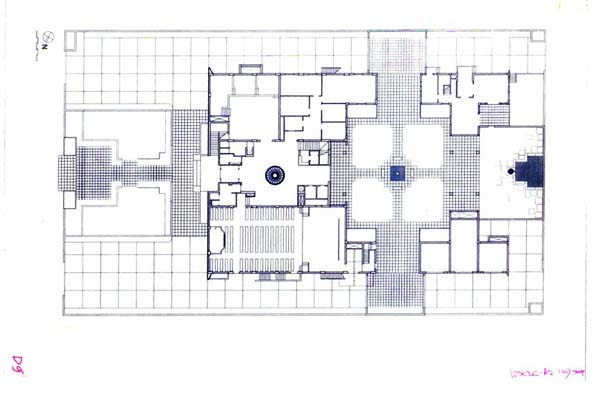

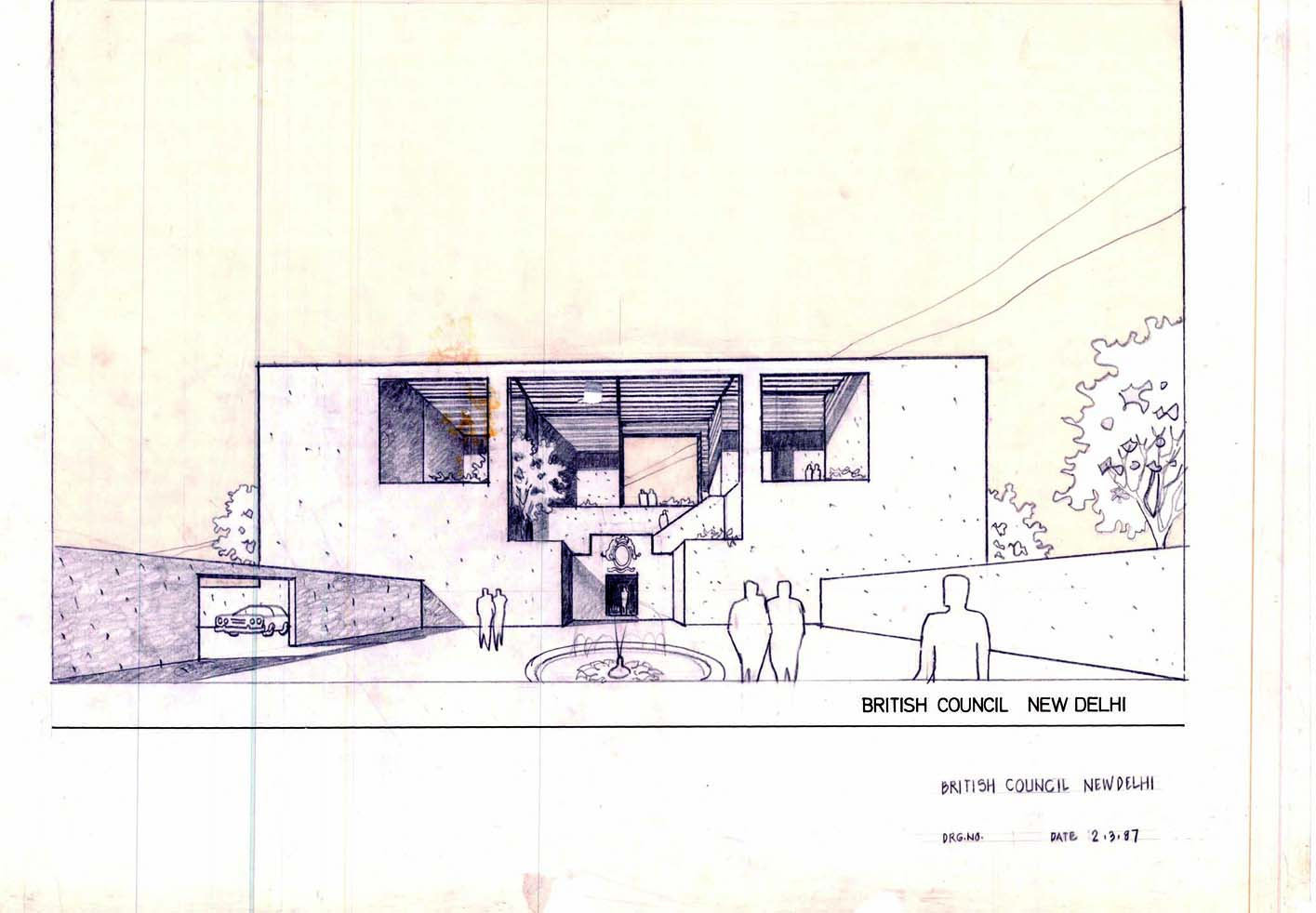

Correa’s principles are universal yet highly rooted in site. His design for the British Council building in New Delhi, completed in 1992, is a wonderful example of this dichotomy. In the exhibition it is represented by a roughly-made, but beautiful foam-board model. A black-and-white photocopy of a mural by Howard Hodgkin is glued to the layered façade, possibly resulting from the conversation between architect and artist as the design evolved. The British Council would have given Correa a pragmatic brief for the building, but he took the opportunity to make a profound comment about the historical influence of external belief systems on Indian culture in a way that reconciles them and presents India – and Britain – as open-minded and tolerant.

In his lecture at RIBA in May, Correa poetically described the layering of culture and ideas in the project, and the wider relationship of architecture to art, film and sculpture. “Architecture is sculpture,” he asserted, “but it also needs to be used by human beings. Doors and windows shouldn’t diminish it, but should complete it.”

-

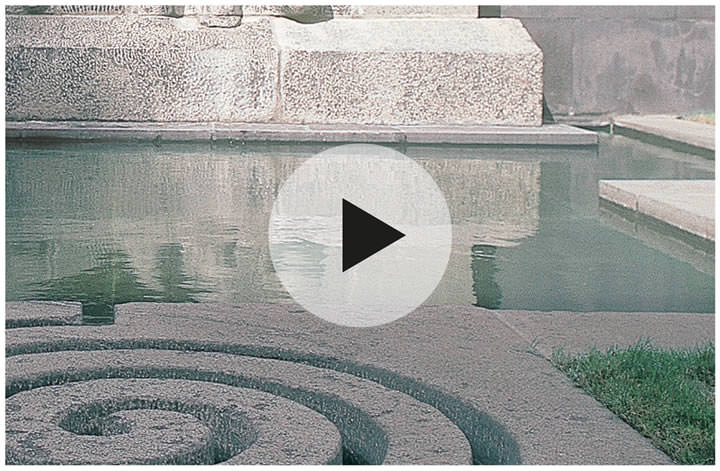

View of a sculpture by Stephen Cox installed in the British Council building in New Delhi. Correa’s idea for the building was to express the three basic cultural identities that have shaped contemporary India: Hindu, Muslim and European. He accomplished this by creating three separate courtyards. Cox’s sculpture sits in the Hindu court, at the point of “Bindu,” or unity. (Photo © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

![]()

Charles Correa in conversation at the RIBA in London with RIBA President Angela Brady in May 2013. (© Video Productions Ltd/RIBA)

-

![]()

View across the inner courtyards, with in the foreground an interpretation of the layout of the Islamic Garden of Paradise.

![]()

The building façade is red Agra stone. (Images this page courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

![]()

Detail of mural by British artist Howard Hodgkins on the main façade, made of black kuddapah stone and white makrana marble.

Correa’s architectural models in the exhibition convey a great sense of conviction and confidence, as evident in the early projects as in the later years. A sectional timber model of his Tube House in Ahmedabad, built in 1961-62, describes the simplicity and strength of the building. It was an early example of Correa adapting his modernist training to consider local climatic conditions. His skillful manipulation of a building section is seen later in the remarkable Kanchanjunga apartments, completed in Mumbai in 1983. Here Correa subverts the traditional principles of a bungalow veranda and applies them to a high-rise, creating generous two-storey terraces within geometrically-complex interlocking apartments. There is nothing predictable or easy-going about Correa’s architecture or his attitudes. His intellect is kept sharp by the culture of Indian society itself, which embraces debate as it deals with striking paradoxes and constant change.

-

![]()

![]()

British Council, New Delhi. The ground floorplan shows the axis running through the building, from the entry off the street on the left through the main building entrance.The view looks back along the axis from its culmination in the Hindu Courtyard. (Images © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

-

Vicky Richardson is Director of Architecture, Design and Fashion at the British Council. She was previously Editor of Blueprint magazine and Deputy Editor of the RIBA Journal. She is a member of the London Mayor’s Cultural Strategy Group and Co-Director of the London Festival of Architecture. She has a degree in architecture from the University of Westminster and studied fine art at Chelsea School of Art and Central St Martins.

![]()

Design drawing for British Council from the Charles Correa archive. (Images © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy The British Architectural Library, RIBA)

»There is nothing predictable or easy-going about Correa’s architecture or his attitudes.«

A throwaway remark by the architect during his lecture, showed that for Correa the most significant projects of his career have been in housing and urban design. Museums are “culture-free, unlike housing,” he said. The RIBA’s exhibition and accompanying public programme, give a strong flavor of the potency of debate on architecture in the sub-continent, but left me wanting more. In particular, the inclusion of Correa’s working and presentation models – such powerful evocations of his design principles - made the absence of original drawings even more disappointing.

Importantly Correa’s gift to the RIBA does not mean the key to his working process will be inaccessible to Indians. Before packing up the archive, Correa spent a year turning every single item into a digital file, and the resulting digital collection will be freely accessible in Mumbai and New Delhi. Contributing to an ongoing debate about modernity in India is vitally important to him. In the closing remarks of his lecture, Correa summed this up beautifully: “It will take time for the confidence to come back to a great civilization that lost every battle for 1,000 years. In India we have to reclaim modernity for ourselves. The whole world has a right to be modern – it’s not a style, it’s an attitude.”![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Into the Desert

FEATURING DENISE SCOTT BROWN

Hey, it’s summertime! At least outside our Berlin office it is – there are strawberry stalls on the streets and temperatures are finally(!) rising. So with issue No. 12 we are turning our attention out to the heat-haze on the wide-blue horizon, and venturing “Into the Desert.” We’re not just talking sand...

![]()

Deserts in South Africa and Nevada. (Photos © Archive of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown)

Issue No. 12:

July 25th, 2013

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Form follows feminine.«

Oscar Niemeyer

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents

Installation shot of the exhibition “Charles Correa - India's Greatest Architect.” In the background, the two-metre-high timber model of the Kanchanjunga Apartments in Mumbai. (Photo: Wilson Yao, courtesy RIBA)

Installation shot of the exhibition “Charles Correa - India's Greatest Architect.” In the background, the two-metre-high timber model of the Kanchanjunga Apartments in Mumbai. (Photo: Wilson Yao, courtesy RIBA)