-

Magazine No. 41

Zvi Hecker

-

No. 41 - Zvi Hecker

-

page 02

Cover

-

page 03 - 04

Editorial

Zvi Hecker

-

page 06 - 13

Space Packers

Zvi Hecker’s career-defining partnership with Eldar Sharon and Alfred Neumann by Rafi Segal

-

page 14 - 15

Housing for the Displaced

Ein Rafa, Israel

-

page 16 - 17

Palmach Museum of History

Tel Aviv, Israel

-

page 18 - 26

Essentially I am a Medieval Architect

An interview with Zvi Hecker by Vladimir Belogolovsky

-

page 27

Mountain Highs

Hecker’s colossal city visions

-

page 28 - 29

Koningin Máxima Kazerne

Amsterdam Airport Schipol, The Netherlands

-

page 30 - 35

The Technion Affair

Breaking and entering in the name of architectural integrity by Zvi Hecker

-

page 36

Fitting Furniture

Modules from Montreal

-

page 37 - 46

Revisiting Yesterday’s Future

A photo essay by Gili Merin

-

page 48 - 54

A Different Language

Polygons against postmodernism in Jerusalem

-

page 55

Hive Talkin’

Balkanising Zvi with Marjetica Potrč

-

page 56 - 57

Tokyo International Forum

Tokyo, Japan

-

page 58

Rubble Rouser

Ruins of good intentions

-

page 59 - 61

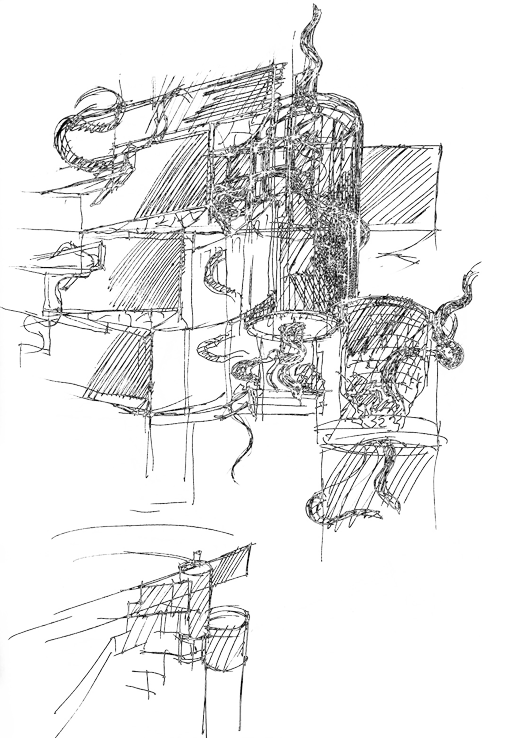

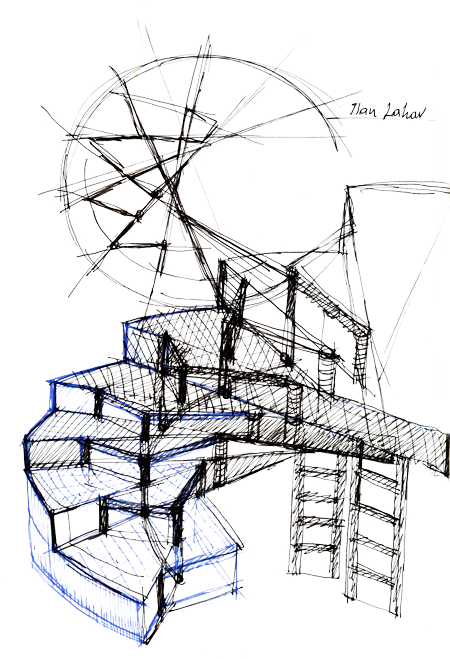

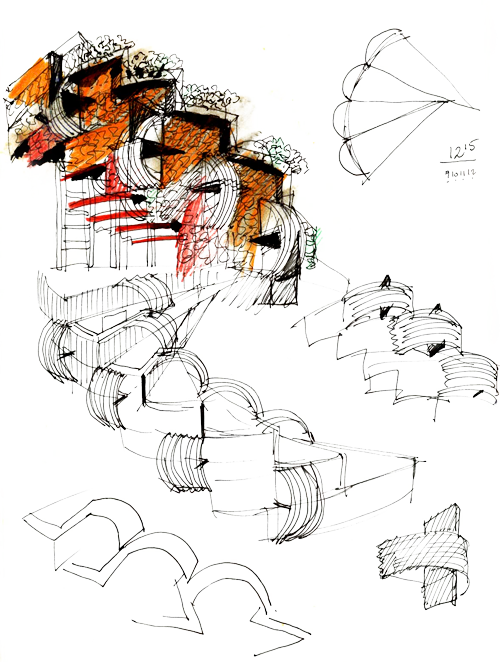

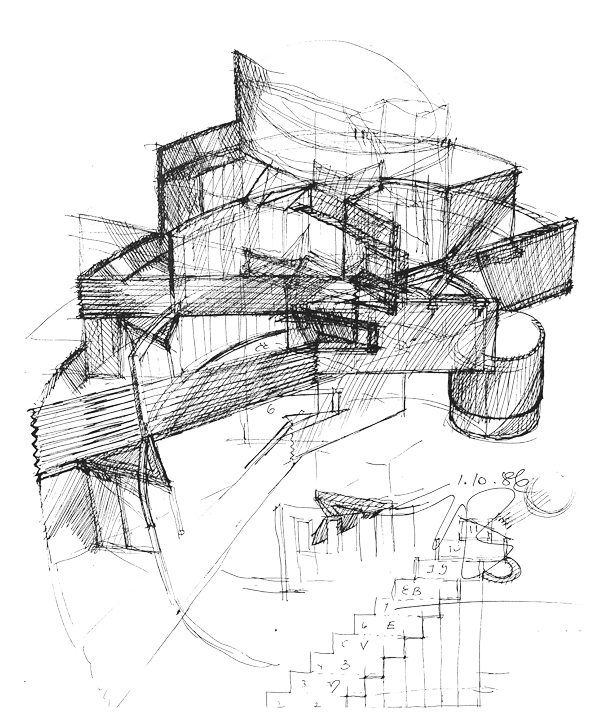

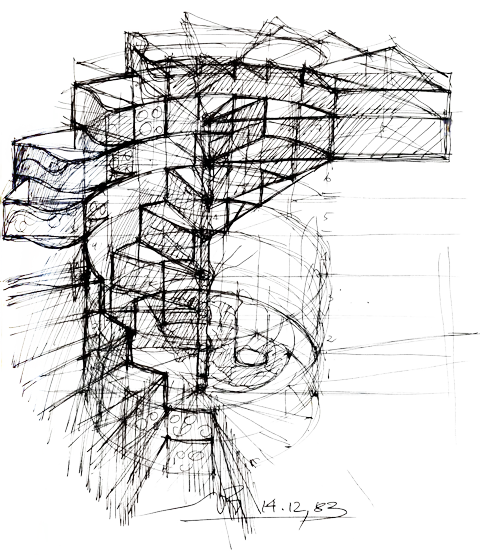

I Draw Because I Have to Think

The mind of the architect artist

-

page 62

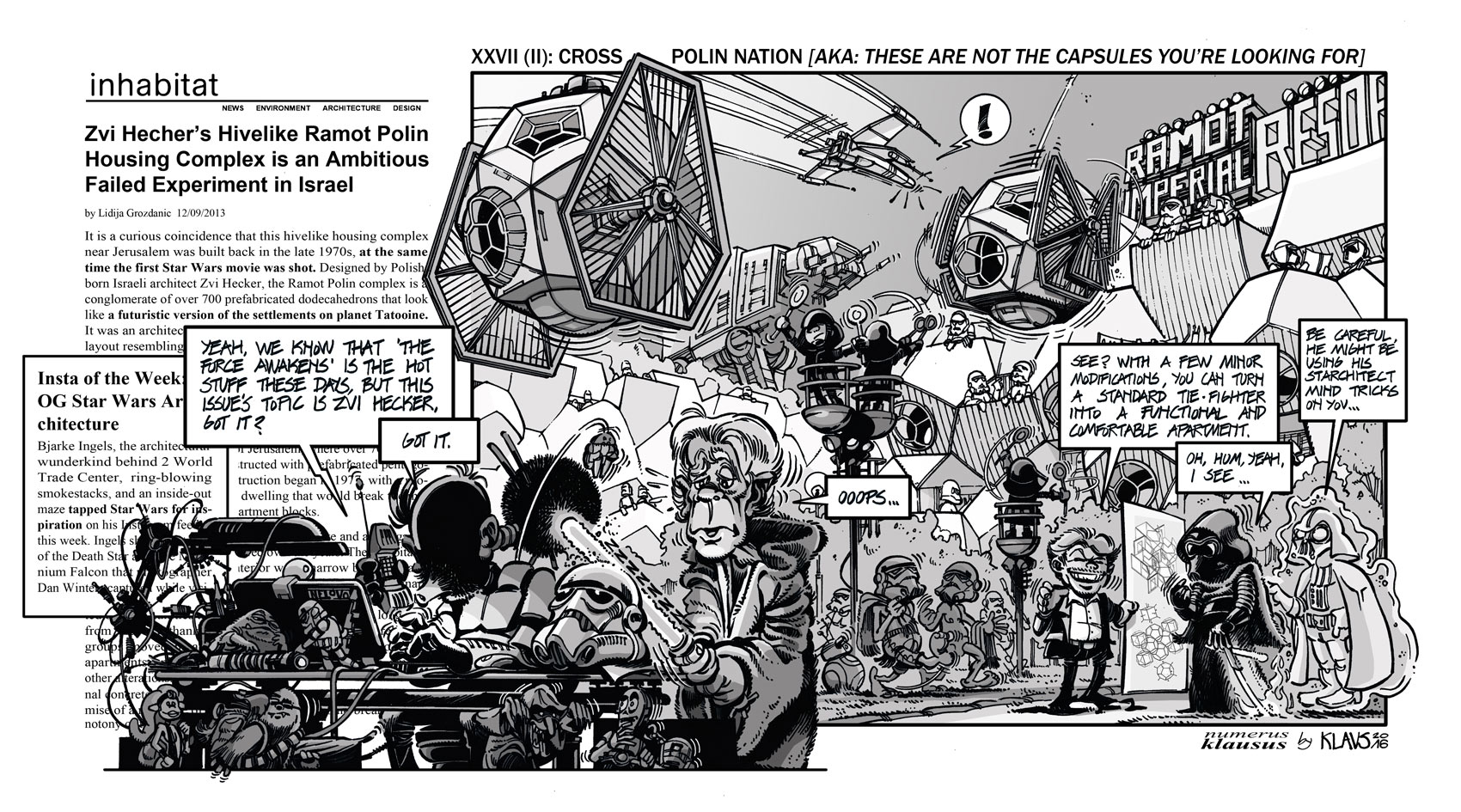

Klaustoon

XXVII (II): Cross Polin Nation

-

page 63

Further Reading

-

page 64

Next

Walk the Line

-

-

uncube’s editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer, Rob Wilson and Fiona Shipwright; editorial assistance: George Kafka; graphic design: Lena Giovanazzi, graphic assistance Janar Siniloo.

uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany’s most-read online portal covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

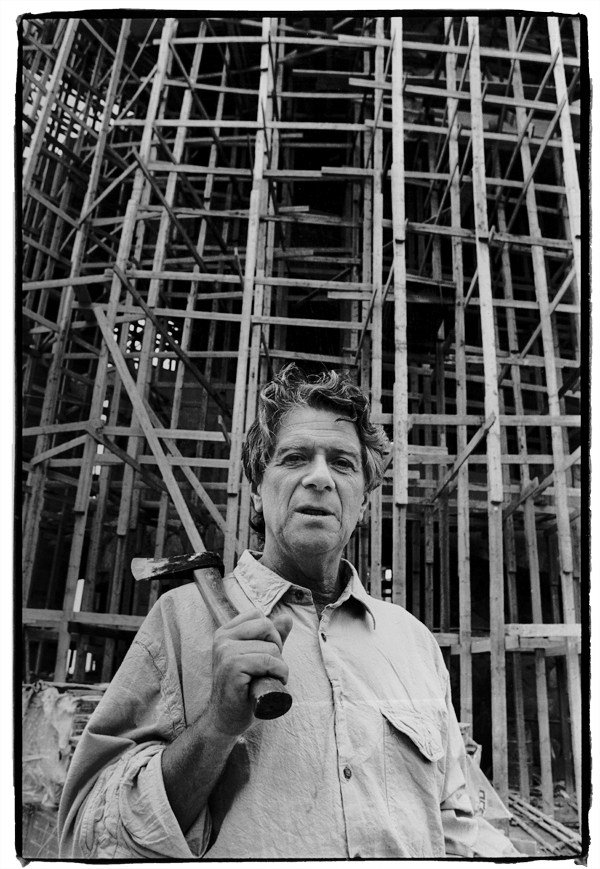

Who is Zvi Hecker?

A painter, architect, superlative draftsman and stubbornly independent thinker, Zvi Hecker has spent the last 60 years using his talents to kick against clients, authorities and mainstream modernism.

From the geometrically modular spatial patterns he worked on with Alfred Neumann and Eldar Sharon in Israel at the beginning of his career, to the spiralling, zig-zagging, nature-inspired, symbolic structures of his later buildings, Hecker has remained throughout an uncompromising, rebellious and committed visionary, sometimes working on site himself to “alter” his designs in defiance of building regulations and even “the will of my clients”.

Let uncube take you to Zvi Hecker’s world: a place of sunflowers, crowbars and polyhedral perfectionism.

As guest contributing editor, uncube correspondent Gili Merin shot a stunning series of Hecker’s buildings in Israel especially for this issue as well as the cover portrait. Big thanks to her and to Zvi Hecker himself, Kristin Feireiss and Paolo Fontana who all made this issue possible.

Cover image: Gili Merin, 2016

-

![]()

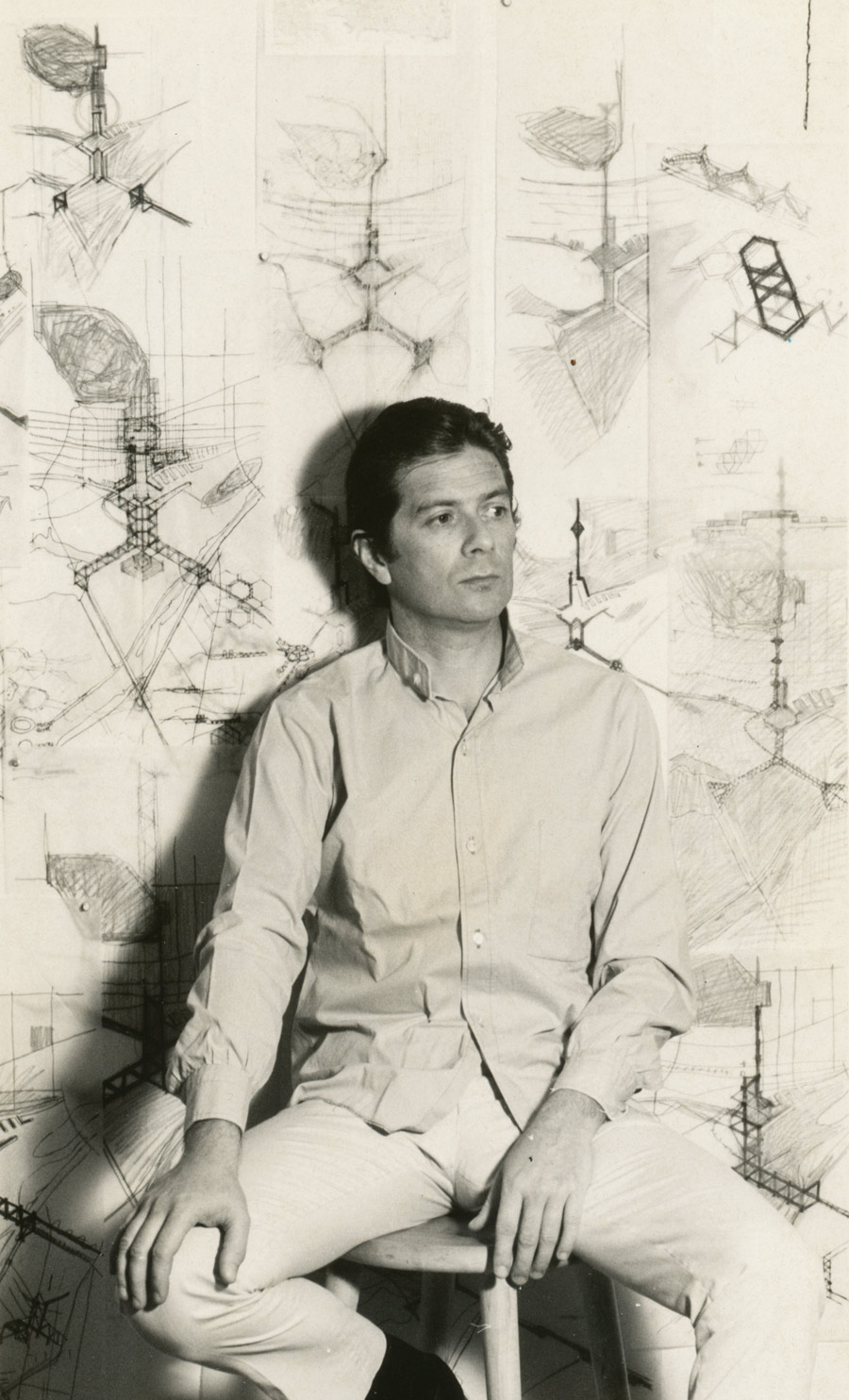

Zvi Hecker, 1970. (All images courtesy Zvi Hecker unless otherwise stated)

Zvi Tadeusz Hecker

was born in Kraków, Poland in 1931 and survived the war years by fleeing with his family to Samarkand in Uzbekistan. In 1949, he returned to Kraków to study architecture before emigrating to Israel in 1950. He completed his architecture studies at the Technion Institute of Technology, Haifa in 1955 and studied painting at the Avni Institute of Art and Design, Tel Aviv until 1957.

In 1959, Hecker opened an architecture office in Tel Aviv with his former tutor Alfred Neumann and co-student Eldar Sharon. Their most important joint projects include the Bat Yam City Hall (1961-63), the military base Bahad 1 in the Negev Desert (1963-69), and laboratories for the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering in Haifa (1964-67). His own later works in Israel included the Ramot Polin housing project (1971-75) and the Spiral House (1984-89).

In 1991, after winning the competition to build the Heinz-Galinski School in Berlin (1991-95) and in the aftermath of the Gulf War, he moved and set up an office in the German capital. He subsequently realised the Palmach Museum of History in Tel Aviv (with Rafi Segal, 1993-98), the Jewish Cultural Centre in Duisburg (with Eyal Weizman, 1996-2000) and most recently finished the Queen Máxima Barracks at Schiphol Airport in the Netherlands (2001-16).

He lives and works in Berlin.

-

![]()

A career-defining partnership with Eldar Sharon and Alfred Neumann

By Rafi Segal

-

![]()

Bat Yam City Hall, Israel, 1961-63. (Photo: Zvi Hecker)

-

In 1959, following his military service, together with his former classmate Eldar Sharon, Zvi Hecker won a national competition for the design of a town hall to be built in the newly founded city of Bat Yam, just south of Tel Aviv. Upon winning the competition, Hecker and Sharon decided to partner with their former teacher at Technion University, Alfred Neumann, to develop their schematic design into a realised building.

Neumann was an experienced architect of Czech origin, who had worked and studied under Peter Behrens and August Perret, and emigrated to Israel a decade earlier. “I felt that [Neumann] should be given the opportunity to build in Israel,” said Hecker later. “Eldar [Sharon] was an easy-going guy and did not mind, especially since both of us admired Neumann.” Having a distinguished professor and dean of the Technion involved in the project was also helpful, not only in securing the commission for the inexperienced young architects, but also assuring the client of a job well executed.The knowledge and experience of the older architect, who had designed and built in the past but had been disconnected from practice since the late 1930s, coupled with the young talent and ambitions of two of his former students, created a dynamic and productive team. Challenging and rethinking architectural conventions were natural extensions of Neumann’s teachings and thought-provoking ideas that Hecker and Sharon had encountered in school.

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

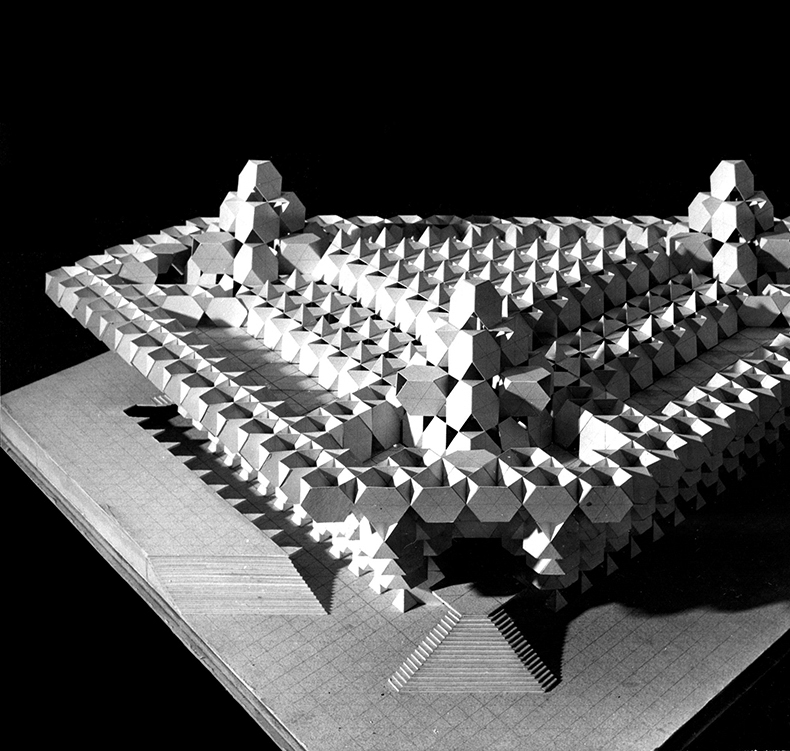

Left and centre: Proposal for Montreal city centre redevelopment, 1965.

Right: Proposal for Natania City Hall, Israel, 1964.

-

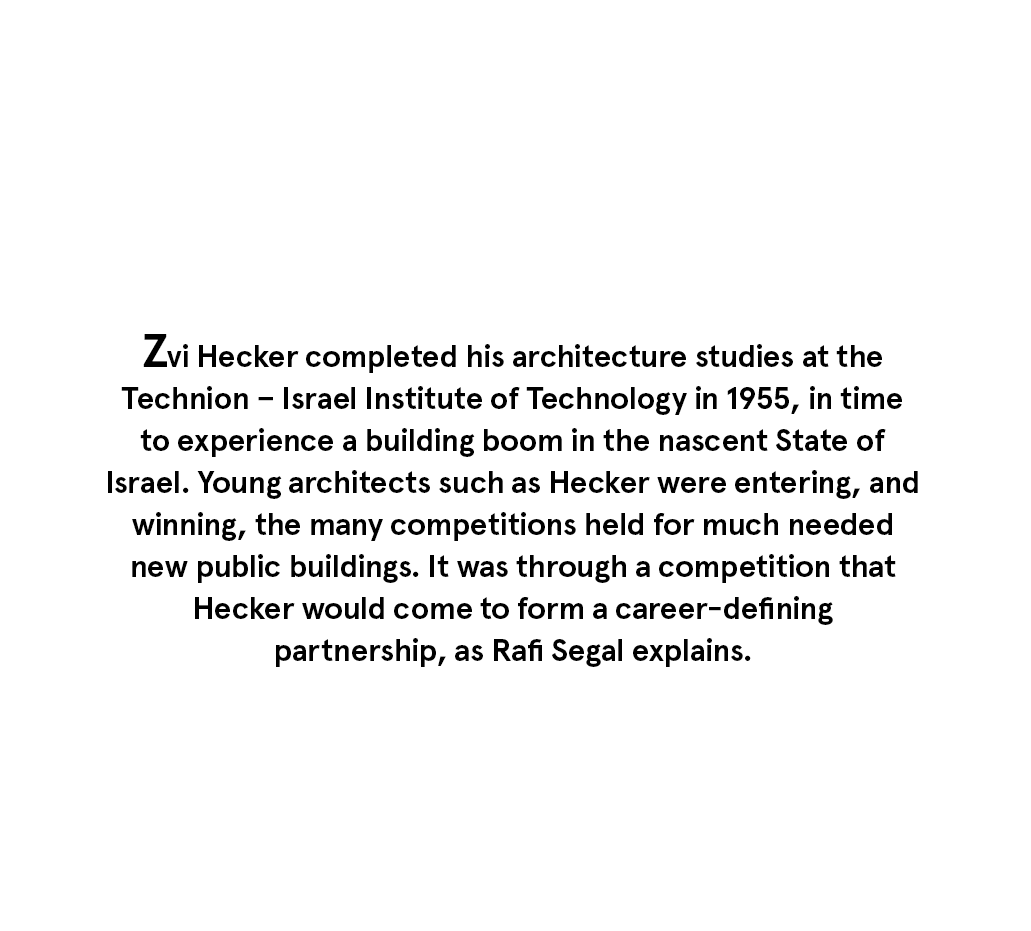

Many of the ideas and approaches that Hecker later carried forward in his own career can be observed in the design of the Bat Yam Town Hall, his first built project with Neumann. Geometry was key, serving both as a tool in the development phase of the design and as the main element of the final architectural expression. Its use went beyond functional necessity and was instead something Neumann implemented as a way to rationalise space and assemble the overall building shape from repetitive units. Hecker would later develop this approach in his own way by creating a unique, particular set of geometric grids for each of his projects.

![]()

One of the primary design moves that Neumann implemented on the early scheme of the Bat Yam Town Hall, and which would become characteristic of his and Hecker’s later works, was the subdivision of space into modules: units of non-orthogonal shape, which acted as spatial blocks through which the building was conceived and then assembled as a whole.

This approach reflected a certain understanding of scale in architecture and the relation between structural and space-enclosing elements. Later termed “space packing” by Neumann, it also provided the means for a new architectural expression.

Drawing for Youth Camp Beitzait, Jerusalem, 1969.

![]()

-

At a time when the architectural world was embracing the austere, minimal aesthetic of International Style modernism, the Bat Yam Town Hall presented an “ornamental” architecture that recalled Islamic patterns and other vernacular building elements from the region. It was the first of several projects in a unique body of design work that Hecker undertook with Neumann and Sharon, which demonstrated an architecture that clearly refused to abide by modern stylistic conventions. However, despite the decorative appearance of their projects, the design logic diverged greatly from traditional conceptions of ornament as applied or superficial patterning. In fact, Neumann’s insistence on “thinking in space” transformed each of their designs into an integrated, spatial-structural frame.

Their design for Bat Yam exemplified geometry’s power to enhance a building’s architectural-artistic expression. This project also taught Hecker the benefits of identifying and implementing a specific geometric pattern for each project – even if arrival at a final version might require several design iterations: but the pattern would always unify the building as a whole whilst maintaining the expression of the smaller units or segments from which it was composed. Hecker would continue to explore these ideas, adopting the notion that architecture results from a process of formal and spatial iterations of a design, based on the project’s geometric pattern.

Following their work on the Bat Yam project, Neumann, Hecker and Sharon found further opportunities to collaborate. Sharon left the partnership in 1964, but Neumann and Hecker continued to work together until Neumann died in 1968. In that short time they produced an extraordinary body of work that gained a level of international recognition unprecedented in Israeli history.

![]()

![]()

Synagogue in the Negev Desert, Israel. (Photo: Henry Hutter, 1971)

-

Rafi Segal is an architect and Associate Professor of Architecture and Urbanism at MIT. His practice and research engage in design on both the architectural and urban scale, with realised and ongoing projects in Israel, Egypt and the US. His work has has been reviewed and exhibited internationally, most notably at KunstWerk, Berlin; Venice Biennale of Architecture; MOMA in New York; and at the Hong Kong/Shenzhen Urbanism Biennale. Segal holds a PhD from Princeton University and two degrees from Technion – Israel Institute of Technology: MSc and BArch. Among his current projects are the design of a new communal neighbourhood for a kibbutz in Israel and curating the first-ever exhibition on the life and work of Alfred Neumann (1900-1968).

This was of great significance not only for their architectural careers, but was also a notable feat in the context of 1960s Israel: a small, young, provincial country without any substantial prior contributions to the international architectural scene.

Through their work together, Zvi Hecker gained the confidence and mastery over geometry to develop his own architectural language. While Hecker’s later designs might seem far removed from the pristine, bare concrete geometries of his earlier work with Neumann, they embody common principles alongside an uncompromising quest to challenge conventions. While an artist’s creativity is continuously nourished and shaped by various influences throughout an entire lifetime, in some cases it’s possible to single out defining events or periods that stand out from the rest. Such was a teacher’s impact upon his student, in the case of Hecker and Neumann.Ramot Polin Housing I, Jerusalem, 1971-75. (Photo: Zvi Hecker)

-

![]()

Housing for the Displaced

Ein Rafa, Israel

1961-62 -

![]()

In 1961, the Israeli Ministry of Housing commissioned Neumann, Hecker and Sharon to design a group of 20 houses for Arab refugees displaced by the Arab–Israeli War of 1948. Making use of basic forms and local materials, the houses could be built easily and fast. Two types were designed: rectangular and square. Stone from the surrounding region was used for load-bearing walls and corrugated metal sheets used for roofing and shade. The houses have since been swallowed up by Israel’s sprawling urbanisation and generic suburbs and not a trace of them remains. p (fh)

Photos and drawings: Zvi Hecker

-

![]()

Palmach Museum of History

Tel Aviv, Israel

1993-98 -

![]()

This museum, designed in collaboration with Rafi Segal, was constructed to honour the Palmach, an elite squadron of the Haganah, the underground paramilitary of the Jewish community in Palestine under British Mandate from 1921-48, credited with contributing to the foundation of Israel. Hecker and Segal’s structure is one of discordant angles and contrasting materials and textures. The interior, housing an exhibition space and 400-seat theatre, is equally complex. Viewed from outside, the overall form of the building rises upwards and outwards from the core, a subtle nod perhaps to the endeavours of the museum’s honourees and a design described by Hecker as “a landscape of the dreams that have made Israel a reality.” p (gk)

Photos: Michael Krüger; drawing: Zvi Hecker

-

![]()

An interview with Zvi Hecker

By Vladimir Belogolovsky

-

The architect, curator and critic Vladimir Belogolovsky met up with Zvi Hecker in his Berlin studio where the conversation turned from flowers and books to radicalism, tradition and putting clients firmly in their places.

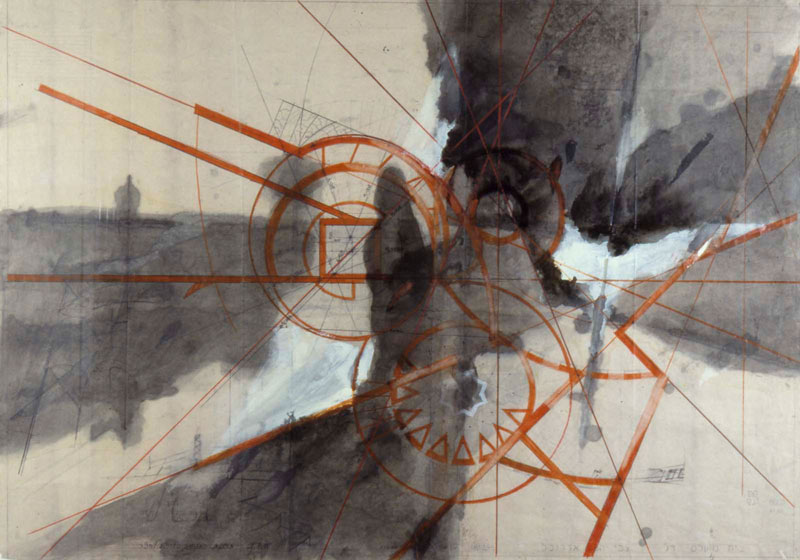

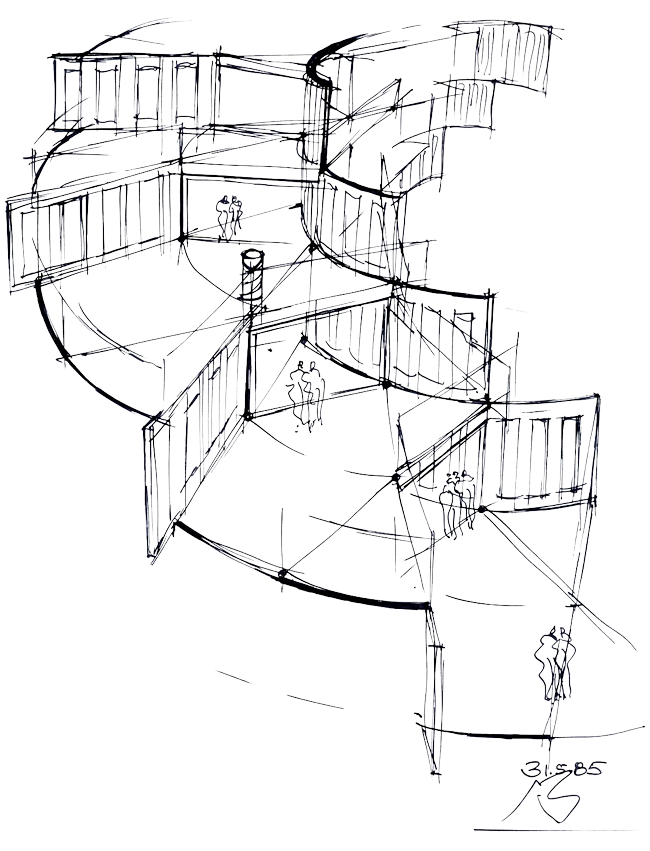

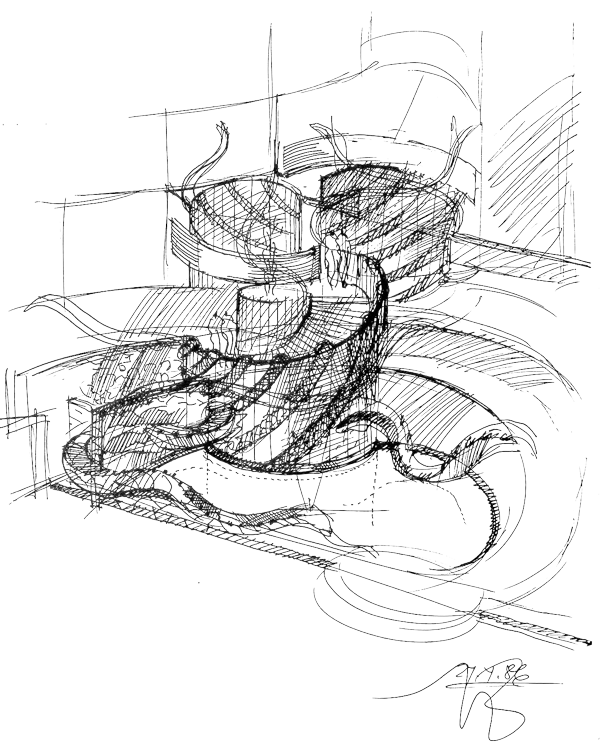

Previous page: Zvi Hecker, 1996 (Photo: Hiepler Brunier). This page: Sketch for Heinz-Galinski School, Berlin, 1991-95.

-

Yesterday, I had a chance to visit the Heinz-Galinski School here in Berlin. Is it true that the inspiration for your design came from the patterns of sunflower seed heads?

This building was the first Jewish school to be built in Berlin after the Holocaust. So coming from Israel, I thought: what could I bring to the children of Berlin? A flower is a good gift and a sunflower is a common flower in Israel. What started out as a sunflower then turned into other things. During the construction, many people who visited the school saw it as a small city with winding streets and courtyards, not just a building. Then we built a plywood model in which we showed all structural walls. It was suddenly very apparent that from the top this model looked like pages of an open book. The Hebrew word for school, “beit sefer”, literally means “house of the book.”

So if you wanted to be clever, you could say that you conceived the school as the house of the book from the beginning.

But if I had started with the idea of a book I might have finished with the sunflower [laughs]. It is the transformation from one idea to another that is characteristic of the process of design. You start with an “a” and finish with a “k” or an “l” or a “z”. This school was a sunflower, then a city and ended up being a book – but it still is the sunflower in a way. The way knowledge is absorbed at the school is similar to how a sunflower absorbs the light. And light is education. The building itself is a piece of education. It is about the learning process, but it is also about experiencing the building itself.

You have used the metaphor of the sunflower in other designs as well, can you explain why it is such a recurring motif in your work?

During World War II, my family was deported to Siberia from the Soviet-occupied Polish territories. I was 12 or 13 when we ended up in Uzbekistan where my teacher, Itzhak Palterer, introduced me to architecture partly through drawing the ruins of Samarkand. It was a difficult time and we survived on sunflower seeds. So the sunflower is very personal to me, but it also incorporates Fibonacci numbers that are connected with the golden ratio. It actually has many values: beauty, colour, nourishment, mathematics, equations, spirals… what else could you find in one flower?

Your school is not just a building, but part of what you have done before and since. It is a work in progress. It is your manifesto in the making – is that right?

At the beginning of the 20th century, there was a notion that we no longer needed protection and everything could be exposed.

-

![]()

Heinz-Galinski School, Berlin, 1991-95. (Photo: Michael Krüger)

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

»For 40 years now, I have been consistently building against the will of my clients.«

Left and bottom: Sketches and model for Civic Centre Ramat Hasharon, Israel (unbuilt), 1986.

Top right: Zvi Hecker at work on the Spiral House, Ramat Gan, Israel, 1984. (Photos: Gil Bernstein and Rina Hering)

-

We started building beautiful glass buildings with nothing to hide because we thought this way we could raise a new, better person, so fantastic we could put him on display. Fortunately, we didn’t succeed. People are what they are and architecture is about people. People are at the centre of architecture, so architecture is about protection. I am essentially a medieval architect – in my architecture one wall protects another wall. The buildings are the walls and the walls are the buildings. Someone said my architecture is about where I build and where I come from. I come from a medieval city, Kraków; I grew up in a desert in Palestine. So this is what was always around me – walls that protect. Whatever form they take is another subject.

Some of your early residential projects are based on modular repetition. Other projects and based on forms that are more free, such as spirals. Are these different ideas or are they part of one idea?

I think, as you get older your work becomes freer. But even my earlier modular architecture, based on a repetition of polyhedral units that I built in Israel, was arranged into open hands, zig-zags and spirals. Underneath there was always an urge to make architecture free and organic. My work has always been based on nature, but it is characterised by a particular rigidity.

So let me get this right: you came up with a building design that started as a sunflower, then it became a city and finally turned into a book. At some point you built a model, put it in front of the client and there it was – a strange beast with acute angles and impractical spaces. Was that something you had to fight for? What was the client’s initial reaction?

This was a competition project. After I won it, both the engineers and the client said it could not be built. Nevertheless I succeeded in building my competition project without any compromise. I lived very close to the construction site and I spent a lot of time there, supervising the work. I made it work.

For 40 years now, I have been consistently building against the will of my clients. Sometimes I hid my drawings from the clients and directed the builders personally. It is fantastic when you can do things regardless of what others say. I had a vision and I went ahead with it.

Proposal drawing for Holocaust Memorial, Berlin (unbuilt), 1997.

-

![]()

Models for proposed Holocaust Memorial, Berlin (unbuilt), 1997.

![]()

Model and sketch for proposed Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Egypt (unbuilt), 1989.

![]()

Jewish Cultural Centre, Duisburg, Germany, 1999. (Photo: Michael Krüger)

-

Is it still like that even today? What about your latest project, the police campus for the Royal Dutch Military Police near Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam?

Yes, it was very difficult to convince the client and every presentation was like going into a battle. They did not understand why the building had to follow a zig-zag line… The generals tried to convince me to change my design and I said no. They almost fired me… But they didn’t.

Then they realised that their building will be seen mostly from the air and that the zig-zag shape makes it a gateway into the city and the country. And again it is also like a wall of a medieval city. The wall is the city, it includes offices, a school, restaurants, sports facilities, and so on.

What does the open hand symbolise in your architecture?

In middle-eastern cultures, the hand signifies that a human is behind the wall. The Hebrew word for hand is “yad”, and yad also means a memorial like the Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem. Take my Jewish Cultural Centre in Duisburg for example [completed in 2000], it unfolds like an open hand as a memorial to the destroyed synagogue that once stood there. It can also be seen as an open book with five oversized concrete pages.

No one needs to know about these metaphors. Just like you may not know that Brunelleschi used the golden section and perfect circle and square relationships in his Pazzi Chapel in Florence. Still, you go there and you sense beauty and harmony. Here is the same – no one needs to know about the ideas that define a particular building. It is not the roots of the tree that are important; it is the fruit of the tree that’s important.

You are perceived as an “artist-architect”. Is that how you see yourself too?

I see myself on both sides. I exhibit my artworks in art galleries and I exhibit my architectural projects in architecture museums. Sometimes I show my paintings and sculptures to my architectural clients and they say: “So you are really an artist.” I suppose, being an artist is better than to be just an architect. [Laughs.] So I am an artist whose profession is architecture. Anyone can be an artist.

Do you intend your buildings to be works of art?

I intend my buildings to be used by people. Whether they become works of art or architecture is beyond my intentions.

-

Vladimir Belogolovsky (b. 1970, Odessa, Ukraine) is the founder of the New York-based non-profit, Curatorial Project, with a focus on curating architectural exhibitions worldwide. He is the American correspondent for architectural journal SPEECH (Berlin) and the author of six books, including Conversations with Architects in the Age of Celebrity (DOM, 2015) and Soviet Modernism: 1955-1985 (TATLIN, 2010). www.curatorialproject.com

Would you say you are a signature architect? Is that the intention, to find your distinctive voice and express it artistically?

That’s not my intention. It should be my voice because I am doing it. But I am not trying to find a particular expression that would be distinctly mine.

But you like testing your clients and exploring limits…

You know, good architecture cannot be legal; it is illegal!

What do you mean?

Well, look at my Spiral Apartment House in Tel Aviv. It is totally illegal. It goes out of the site’s borders. The construction was stopped so many times, but I kept going, working by myself at night, pushing ahead. This element of being illegal, radical, new, provocative must be present in any art.

So does that make you a radical architect?No. I could be building pyramids in Egypt, temples in Greece or castles in the Middle Ages. I consider myself a traditional architect. I am not revolutionary. Some clients may see me as radical but that is because of how I interpret what tradition is in architecture.

Well, being radical is also a tradition – building something that never has been done before, whether it’s pyramids, temples or castles. Part of architectural tradition is breaking traditions. Is that what you teach your students?

Architecture has the longest tradition. Maybe 3,000 years or more. But schools start teaching the subject from so-called modern architecture. I think students should learn from old cities as well, such as Rome, Paris, Barcelona, Kraków. I like talking to students about the history of architecture. I would send them to one particular street in Paris to see, analyse, and draw those wonderful buildings. There is such a great variety of buildings there. All you need to do is study their history, composition, proportions, details, and make what you want out of what you learn.

How do you explain to students what architecture is?

I don’t know myself! Perhaps that is why I teach. I don’t know what architecture is; I only know what architecture was – I know its history. I need to find out by building new projects, my own projects. You may find similar threads in my work, but every time I start a new project, it seems to me that I start from zero. I

-

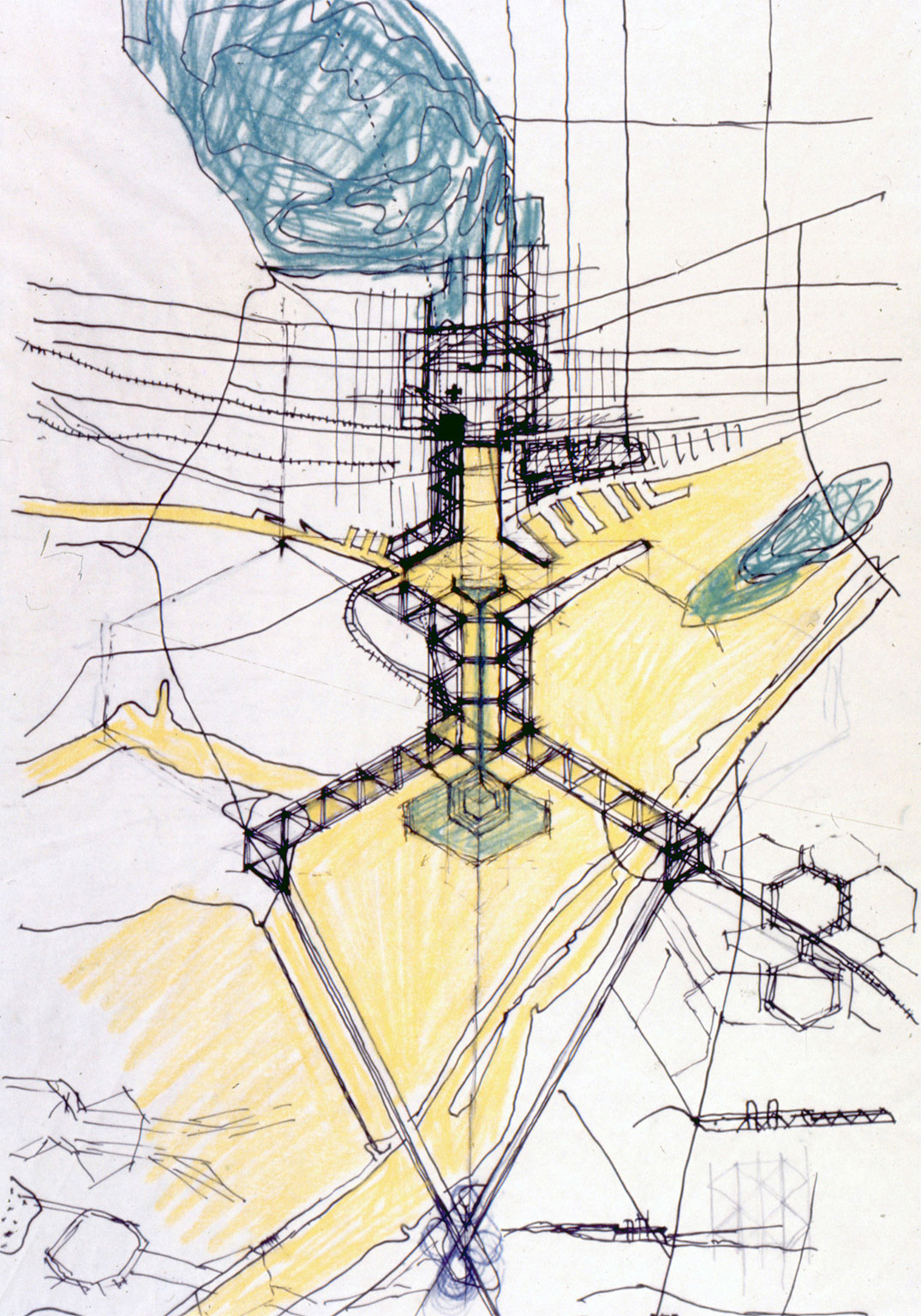

Mountain Highs

In 1993 Zvi Hecker started a series of sketches in which he turned a mountain panorama into a concept for mass housing. Looking for freedom from the “obsessive repetition of the parallelogram grid” that continues to define mass housing, Hecker’s fascination with his “Mountains” has persisted through much of his later career, with proposed and re-proposed iterations of the scheme for Rotterdam, Bucharest, Berlin, London and, as seen here, as a transformation of Amsterdam’s former harbour areas. Colossal in vision as well as scale, these peak projects have yet to find a client. See drawings from the whole range of “Mountains” on the uncube blog. I (gk)

Mountains Housing Project, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1999.

-

![]()

Koningin

Máxima KazerneAmsterdam Airport Schiphol,

The Netherlands

2001–16 -

![]()

This brand new project unites several departments of the Royal Dutch Military Police in one place, providing living, working and training facilities for 1,500 police officers responsible for security at Schiphol Airport. For his winning entry to the architectural competition, Hecker proposed a fortress-like plan comprising high, closed buildings lying along the borders of the site, with smaller buildings and open-air facilities set behind – in effect creating a contemporary version of a medieval citadel wall protecting an inner courtyard. To meet security requirements, the first two floors are monolithic, closed and cast in grey concrete, whilst the two lighter, upper floors are made of glass and coloured metal. The zig-zagging figure of the “wall” shows its best profile to the sky, clearly visible to those arriving or departing Schiphol Airport by air. p (fh)

Photos: Oliver Scheffler; model: Zvi Hecker

-

The Technion Affair

By Zvi Hecker

-

What do architects do when the client starts messing about with crucial parts of their design? Some might sob quietly at home, some might complain in public, most would most certainly file a lawsuit. Not Zvi Hecker. When the staff of Technion University altered the lighting concept for his and Neumann’s 1960s faculty building design in Haifa, Hecker turned up on the construction site – at first with a paint brush and then with a crowbar at night. Here he recalls the struggle with the users of his building which came to be coined “The Technion Affair” by the Israeli press.

![]()

Previous page: Photo by Moshe Gross. This page: Background photo: Zvi Hecker; insert: Ella Hecker

-

The “Technion Affair” had all the essential features of a classic melodrama: an uncompromising artist fighting the corrupt villains. What began as a difference in opinion between the user and the architect evolved into a serious disagreement and eventually erupted into an open conflict. The press in Israel coined it “The Technion Affair”. It unfolded gradually, but with precise predictability.

The Aerospace Engineering Lab at the Technion in Haifa is a kind of self-conditioning structure breaking away from flat curtain-like walls and their many sun-breaking systems. It regulates the intensity of indirect light entering the laboratory space. Reflected onto the prismatic walls, the light illuminates the interior. In order to increase the intensity of the reflected light, the walls had to be painted white and yellow. Special windows were also incorporated into the roof.

The faculty professors objected to our scheme from the beginning of the design. At first the pretext was the excessive cost of construction. When this proved incorrect, a new obstacle was found: the design provided insufficient natural light for their work. It became evident that the professors’ objections were rooted in the very originality of the design itself.

The faculty professors’ opposition to our design led the president of the Technion to end the controversy with a public opening of the building. This occasion would be used to declare the building complete though it had not yet been painted nor had the special windows yet been installed in the roof. My objections to this decision were dismissed by the Technion.

On the morning of the opening ceremony, with the help of my assistant Henry Hutter, and unnoticed by the catering staff preparing the reception, we started to paint the interior of the prismatic walls in white and yellow, as specified in our plans. -

It took some time for the catering staff to find out that something strange, and totally unrelated to the preparations for the opening, was going on. By then we had already painted a noticeable part of the interior walls. Once informed of our activities, the Technion’s administration director promptly arrived and commanded us to stop painting and to leave the premises immediately. We refused; he presented us with an ultimatum: if we didn’t leave, we would be removed by force.

We decided we’d welcome such a scenario, since journalists were already arriving and our protest would certainly be a much more interesting story than the opening speeches.

As we continued to paint, the next to arrive was Al Mansfeld, the dean of the Faculty of Architecture, on a mission from the president to try to convince me to stop painting. I asked Mansfeld to bring a letter from the president confirming that the building would indeed be completed as designed. It was difficult to believe, but, just before the opening ceremony, Al Mansfeld arrived with the letter. We could celebrate, but it would not be for long.

As articles and photos on our painting protest and its background appeared in the daily press, we noticed that simultaneously, newspapers were carrying an ever-increasing number of reports about important scientific findings being carried out by scientists at the Technion. It was an obvious public relations campaign by the Technion to improve its public image, undermined by its handling of the controversy. It seemed to be in preparation for something to come.

Sure enough, the contractor had received instructions to install simple windows in the roof instead of the reflecting ones we had designed.Photo: Zvi Hecker

-

I called the office of the president. His secretary said that he had left for the US one day previously and would be away for two weeks. I called Al Mansfeld, but he knew nothing about the instructions left by the president before his departure.

The contractor informed me in confidence that, following the installment of frames for simple windows in the roof, he had been ordered by the Technion to install permanent windows, but not of my design.

I consulted my lawyer, who had doubts about the likelihood of obtaining a court injunction since the Technion was in the process of completing the work. He thought that suing the Technion for breaching architect’s rights would be lengthy, costly, and not necessarily successful.

I felt that there was no other option left but to prevent the Technion from accomplishing their scheme myself.Photo: Moshe Gross

-

I arrived in Haifa with Henry on the night of October 31, 1966. At 2am we drove up to the Technion campus. It was very quiet. We climbed onto the roof of the building, equipped with two heavy metal crowbars. In less than two hours we’d bent and twisted all 28 window frames so that they could not be repaired and no permanent windows could be installed. Because the campus was very quiet and our work was very noisy, we feared being caught before having had a chance to complete our task. However, we were lucky; security was not so tight. We hung the “tools of the crime”, the two crowbars, on a tree and drove back to Tel Aviv. On the highway, a police patrol stopped us. We wondered how fast they had been informed of our actions. Fortunately, it was only a blinking headlight that had caught their attention. We arrived in Tel Aviv in the morning. It was November 1, 1966 and I went directly to the hospital where my wife Dvora had just given birth to our daughter Ella.

I think Dvora waited until I had finished my work. My lawyer Aahron Aderet, when informed of my actions, resigned in protest. Amos Eylon, a journalist at Haaretz, maintained that this was a case for the police and not for his newspaper. He had not foreseen the public interest it would accrue. I had also called the police and admitted to breaking the windows of the Technion building. The “Technion Affair” received yet new acclaim in the daily press. I was summoned to the police headquarters in Haifa for interrogation, but surprisingly no criminal charges were laid against me. The press impressed even the police. The Technion, however, sued me for damages to its property.

My new lawyer, Eliezer Levin, asked for a court injunction against the Technion and, despite the fact that I had taken the law into my own hands, we were granted the injunction. The Technion was not allowed to install their simple windows until the case had been settled. The newspapers carried sensational stories about the architect’s night adventure, but a significant cultural aspect of the case was also revealed. An open letter, signed by the most prominent Israeli artists, writers and poets, supported my actions as carried out in defence of cultural values. The Technion was silent and no reports about new inventions by its scientists appeared in the newspapers.

Only in Parliament, in response to a question posed by Member of Parliament Uri Avneri, the then Prime Minister Golda Meir deplored my actions as antisocial behaviour.

The “Technion Affair” raised public awareness of the architect’s rights to his work. On a personal level, I ended up with many copies of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead sent by enthusiastic students. IPhoto: Zvi Hecker

-

Fitting Furniture

During a brief spell teaching in Montreal in the 1960s, Zvi Hecker delved into the world of furniture design, some samples of which were built by his former assistant and carpenter Henry Hutter. Modelled here by his family in 1969, Zvi’s furniture came from the same modular design ideas as his architecture, taking a simple geometric element and repeating it to create a connected system of seats and coffee tables. Considering the difficulties involved in find furniture to fit snugly into some of those acute corners in his housing projects, it’s a shame the system never made it beyond the prototype stage. p (gk)

Photo: Zvi Hecker

-

![]()

Photography and text by Gili Merin

uncube correspondent Gili Merin travelled around Israel searching out the key experimental buildings from Zvi Hecker’s early career to see how they’ve fared over the years. She found most of the projects largely intact and still in use, but with their often extreme formulistic geometries altered and adapted by their users.

-

![]()

»The Bat Yam Town Hall, standing among the homogenous residential units now surrounding it, looks as alien as it did in 1963. Its basic form and outer appearance seem unchanged. You need keen eyes to notice the missing rooftop ventilation shafts that were removed due to supposed security issues.«

-

»Over the years, random additions and makeshift solutions were added: air conditioning, pipes and extra cables. Whereas with most other buildings these would be visual nuisance, on the colourful façade of Bat Yam’s Town Hall they even seem to embellish the geometrical complexity with an added layer of randomised accessories.«

-

»The military training campus Bahad 1 rises from the Negev Desert like a futuristic micro-climatic urban entity. It could be an internationally acclaimed architectural monument, if it didn’t also happen to be a high security facility for the Israel Defense Forces.

The concrete complex is kept in good shape by cadets in a never-ending cycle of cleaning and maintenance, almost like a ritual of architectural appraisal.«

![]()

-

![]()

»With its austere façades, repetitive structure and the obsessive gardening of the inner courtyards, the edifice has the atmosphere of a cloister or penitentiary. An exception is the synagogue – an autonomous crystal with triangular windows. Unfortunately, it is no longer in use, making it a relic of Neumann’s morphological doctrine, shut and sealed.« -

![]()

»The Dubiner Apartment House is the only project by Neumann, Hecker and Sharon that is listed as a monument and has thus not fallen victim to additions or severe alterations.«»The most striking feature to me is the balance of density and porosity, of shared and private outdoor spaces, and how greenery has in the meantime overgrown the building almost completely hiding it from the street.«

![]()

-

![]()

»Perhaps Hecker and Neumann’s purest morphological experiment was the Technion faculty building, set on a steep slope above Haifa. It was also their last joint project before Neumann left for Canada.«

-

»With the construction of the Spiral House in Ramat Gan, Hecker became a one-man bricoleur community, creating perhaps the most astounding architectural object in Israel.«

-

Gili Merin (b. 1987 in Jerusalem) is an architect, photographer and journalist based in Tel Aviv and Berlin. She studied architecture at the UdK Berlin, Waseda University in Tokyo and recently graduated from The Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem. She has worked with AMO*OMA in Rotterdam, with COBE in Berlin and ArchDaily in Santiago de Chile. She publishes her writings and photography in numerous international print and online publications including Mark Magazine, Wallpaper, Haaretz, ArchDaily, Business Insider, The Huffington Post, Quaderns, Detail and Frame.

gilimerin.com

»Its iconographic incompleteness leaves little room for makeshift tenant adaptations, so the Spiral House is probably Hecker’s most precise and immutable architectural piece.«

![]()

![]()

»He used to live in the Dubiner House opposite, which allowed him to keep a close eye on the building, spending many days on the construction site himself.«

-

The world just got littler...

The world just got littler...

To hold one in your hand is to hold a tiny power pack, but its energy comes from the greatest source of energy we know. The sun charges it and it charges your life at the same time.

Maybe you’re a Zimbabwean child that needs a light to study by at night. Or you might be headed to the Roskilde Festival and you need a light for your tent. Maybe you’re going hiking with your friends and you want something better than a battery-powered torch. Or you work in a Himalayan village and you need a hand-held light to guide your way back home through the mountains. You could be a design-nerd and you want to own a little light designed by Olafur Eliasson.

Or you’re a Sudanese mother and you want to prepare your family’s meals under a safe and healthy source of light. Or maybe you have a young family in Berlin and you want a colourful way to teach them about sustainability.

Whoever we are, wherever we go, there is more that connects us than divides us. And one of the most important things that holds us together is that we all need light in our lives. Of course the greatest light we have is the one we all share: the sun.

Sometimes it’s nice to feel that the big wide world just got a bit littler.

Welcome to our little world:

www.littlesun.com

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

Polygons against postmodernism in Jerusalem

Text by Rafi Segal, Photography by Gili Merin

-

With the changes in Israeli society that followed the 1967 Six-Day War – during which Israel conquered the West Bank, Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights, thus more than doubling its size – came massive urban expansion and architecture of a new kind. Rafi Segal traces how the design and construction of a single project, Zvi Hecker’s Ramot Polin housing complex on the outskirts of Jerusalem, came to embody and yet defy this nationwide change.

The unification of Jerusalem under Israeli control in 1967 prompted a national building project of urban expansion through the construction of new neighbourhoods and settlements on Jerusalem’s surrounding hilltops. These aspired to echo the historic architecture of the old city of Jerusalem and thus establish a direct visual connection between the old and the new. The resulting architectural style of stone façades, arches and other “old Jerusalem” vernacular elements was so dominant that in some cases it led to the dressing of modernist pre-fabricated concrete slab buildings with local stone and arches.

With the focus on the physical and symbolic expansion of Jerusalem came a paradigm shift in Israeli architecture that turned away from the modernism of the 1960s in favour of the “post-modern” Jerusalem architecture of historicised stone façades. Architectural interests also changed – in material: from 1960s exposed concrete to Jerusalem local stone; in form: from abstract geometric expressions to traditional historicism; in construction methods: from pre-fabricated industrial building to traditional mason work; and structurally: from the exposed structures of modernism to concealed and hidden structural systems.![]()

![]()

-

»Ramot Polin can be seen as a last attempt to resist the new wave of historicised architectural postmodernism in Israel at that time.«

-

![]()

-

Needless to say that this paradigm shift left no room for the earlier experimental architecture of the 1960s of which Alfred Neumann, Zvi Hecker and Eldar Sharon were the strongest propagators.

The pre-fabricated Ramot Polin housing complex designed by Zvi Hecker in the early 1970s can be seen as a last attempt to resist this wave of historicised architectural postmodernism (which quickly became mainstream), in favour of an alternative architectural path of new expression and form. It was an almost impossible task. Refusing to accept the old city vernacular as a model for this new complex, he drew on other metaphors, including the form of an open hand. This can be seen in the five-fingered structure of the neighbourhood’s layout, as the topography and landscape enter as public space the voids between the “fingers”. In keeping with the hand analogy, the number five reappears in the form of the dodecahedral solids that constitute the volumetric units that create the spatial pattern of the Ramot building’s main façades.

![]()

»Echoing the wild rock formations of Jerusalem’s hills, the project resembles a series of exaggerated wall-like structures.«

Echoing the wild rock formations of Jerusalem’s hills, the project seems to resemble a series of exaggerated retaining wall-like structures and in such a way engages with the landscape like none of the other new “historicised” Jerusalem neighbourhoods built at the time.

Architecturally, the Ramot project followed Alfred Neumann’s space-packing approach: a stacking of repetitive spatial elements as a means of creating a deep building envelope to function as a “filter” for the strong Israeli light and climate. This system naturally lent itself to pre-fabrication since the overall building was conceived as an assembly of repetitive units, of room-like size, which could easily be produced from pre-cast concrete elements. The staggering of the buildings’ floors enhanced the expression of this stacking while creating balconies open to the sky, a programmatic requirement that enabled the designated tenants – Polish Orthodox Jews – to practice the “Sukka” ritual, in which a temporary hut is built under open skies during the week of the holiday Sukkot. -

Rafi Segal is an architect and Associate Professor of Architecture and Urbanism at MIT. His practice and research engage in design on both the architectural and urban scale, with realised and ongoing projects in Israel, Egypt and the US. His work has has been reviewed and exhibited internationally, most notablely at KunstWerk, Berlin; Venice Biennale of Architecture; MOMA in New York; and at the Hong Kong/Shenzhen Urbanism Biennale. Segal holds a PhD from Princeton University and two degrees from Technion – Israel Institute of Technology: MSc and BArch. Among his current projects is the design of a new communal neighbourhood for a kibbutz in Israel and curating the first-ever exhibition on the life and work of Alfred Neumann (1900-1968).

Ramot Polin spoke a different language of architecture to all the other Jerusalem neighbourhoods built at that time, in form, expression, association and through the concepts it drew on. While the project set out to demonstrate that the rigidity often associated with pre-fabricated construction techniques can be overcome to produce non–conventional (and non-orthogonal) forms, by the time of its completion this argument was no longer relevant. Rather than a catalyst for new and original expression, post-1967 Israeli architecture was now valued for its ability to mimic old forms and create a direct link with past styles, reflecting a cultural preference supported by political-economic forces and a change in the country’s labour source.

Israel’s government-supported pre-fabricated building industry, which developed throughout the 1950s and 60s in response to a lack of skilled manual labour and the desire to maximise efficiency in producing housing for new citizens migrating to the country, was highly advanced by the end of the 1960s. But the conquering of the West Bank provided cheap, skilled, Palestinian stonemasons and, as a result, the national pre-fab industry declined sharply. In fact, halfway through the construction of the Ramot Polin project the Ministry of Housing replaced the construction company supplying the modular elements with a new one, to finish the work using conventional building methods. This change in the manner of construction led Zvi Hecker to discontinue the original design and produce a completely different one for the remainder of the project.

Therefore, through the architecture of its two building phases, Ramot Polin, upon its completion in 1985, evidences, in a single project, a profound shift in Israeli architecture, namely the end of attempts at new expression and the rise of a nationalist style “historicised” in order to prevail and further conquer. I![]()

-

Hive Talkin’

Slovenian artist Marjetica Potrč’s work often investigates the clash between the strict order of modernism’s architectural and urban schemes and their inhabitants’ needs and desires. Her 2011 installation, In a New Land, reconstructs a single module of Zvi Hecker’s Ramot Polin housing project, nicknamed “the Beehive” for its distinctive structure. The work includes an example of one of the self-built rectangular additions which many inhabitants have added to the dodecahedral layout, which “interrupt” the project’s strict formal coherence. Potrč presents this action as an inspiring, bottom-up critique of modern concepts of a “functional city” and as a “balkanisation” of an ideology that puts the purity of form before people’s freedom of choice in determining how they want to live. p (fh)

Marjetica Portč: “In a New Land” at Galerie Nordenhake Berlin, 2011.

(Photo: Gerhard Kassner, courtesy the artist and the gallery) -

![]()

Tokyo

International ForumTokyo, Japan

Competition entry 1988 -

![]()

In the late 1980s, a competition was held for a new conference centre, the International Forum, in Tokyo city centre, on a site formerly occupied by the city hall between Tokyo Station and Yūrakuchō Station. Heckel collaborated with Amir Ofer to propose an elevated podium that would fill the site, its height corresponding with the differing elevations of neighbouring buildings. Two conical structures were designed to grow out of this platform: one in glass with steel beams, the other as a negative, inverted form cut out of the podiums’ mass. A serpentine gallery twines around them, connecting both cones and providing a floating promenade. The result is a building design with a powerful twisting, dynamic; a struggle of opposing forces, frozen as architecture. Unfortunately, the design remained frozen at the model stage as well when the jury decided to opt instead for a somewhat more conventional design by Rafael Viñoly, which was completed in 1997. p (fh)

-

![]()

Rubble Rouser

The asymmetry and as-found aesthetics of projects such as Hecker’s Spiral Apartment House are recalled in his “Ruins of Good Intentions”: a readymade assembly taken from the rubble of a freshly demolished wall at Neumeister Bar-Am Gallery in Berlin during 2014. Upon seeing the rubble Hecker was “impressed with the uniqueness of the forms” which “cannot be replicated without precise handiwork”. Rearranging the fragmented bricks, still caked with cement, Hecker housed them within the safety and purity of a glass cube, presenting them as as valuable evidence of something once built with love, care and: good intentions. p (gk)

“Ruins of Good Intentions”

at Neumeister Bar-Am Gallery in Berlin, 2014.

(Courtesy Neumeister Bar-Am) -

![]()

![]()

By Zvi Hecker

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

Computer drawings are a necessary means of communication between the architect and his or her collaborators, and, eventually with the construction people on site.

Sketches and hand drawings are in less demand these days, though their importance and usefulness have lost none of their validity. The significance and uniqueness of hand drawings lies not in the clarity of their message but in their inherent imperfection. They communicate with no one but their creator.

As our mind is never in complete control of our hand, it is free to create signs, left open for interpretation. Not once was I surprised at how hand drawing can evoke possibilities that most probably I would not have been able to imagine consciously.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

All images: Hecker’s working drawings for Spiral Apartment House, Ramat Gan, Israel, 1984-89.

-

As arguably the most complex of all arts, architecture has had to address many contradictory demands and conflicting interests within its overall design. No successful solution can be reached by sequential analysis but rather by intuitive synthesis.

In this respect, hand drawings help to channel the vague ponderings of the mind into visual images of a germinating concept. It is then up to the eyes to trace and decode its meaning.

The architect’s way of thinking is through his eyes. I -

![]()

-

FURTHER READING

Blog Building of the Week03 Jun 2015

Socialist Labour to Capitalist Luxe

Jacob Rechter’s Mivtachim Sanitarium transformed

Magazine Essay37

A Fine Sculptural Mind

The Aesthetics of Zaha Hadid by Jonathan Bell

Blog Review04 Sep 2014

Architecture is War

Lebbeus Woods Exhibition at the Tchoban Foundation, Berlin.

Blog Review29 Sep 2015

The Conflict Shoreline

Eyal Weizman and Fazal Sheikh evidence climate change in the Negev

Blog Berlin01 Aug 2015

Radically Modern in 60s Berlin (4)

Interview with Daniel Libeskind

Magazine Interview33

Otto and the Open System

Georg Vrachliotis in conversation with Jean-Philippe Vassal

Search our archive! -

![]()

![]()

“Easier Taken Slow”, Masterplan for the corridor Durrës-Tirana, 2014. (Courtesy Dogma, Studio B&L)

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Don‘t fight forces, use them.«

Richard Buckminster Fuller

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents