-

Magazine No. 38

Death

-

No. 38 - Death

-

page 02

Cover

-

page 03

Editorial

-

page 05 - 12

Memento Mei!

The strange ternary work of Argentina’s Francisco Salamone

-

page 13

A Tomb with A View

Le Corbusier’s Grave

-

page 14 - 15

Añorbe Cemetery Extension

Navarra, Spain

-

page 17 - 18

Funerary Shelter

Pardesiya, Israel

-

page 19

Towers of Silence

The Zoroastrian way of death

-

page 20 - 28

The Orientation of Hope

An interview with Charles Jencks, co-founder of the Maggie’s Centres by Rob Wilson

-

page 29

The London Necropolis Company

A railway for the dead

-

page 31 - 32

Islamic Cemetery, Altach

Vorarlberg, Austria

-

page 33 - 39

The Great Beyond

Herbert Wright on architectures of the afterlife

-

page 40

Murder Most Marple

Pocket-sized crime scenes

-

page 41 - 43

The New Crematorium

Stockholm, Sweden

-

page 44

Where Ideas Go to Die

The Palace of Failed Optimism

-

page 45 - 51

Who Wants to Live Forever?

Arakawa and Gins' Reversible Destiny Lofts by Léopold Lambert

-

page 52

Modernist Monsters

An architecture horror classic

-

page 53 - 59

Protestant Death Ethic

Leon Berger’s Southampton Crematorium by Owen Hatherley

-

page 60

Saving Us From Ourselves

The Golden Gate Bridge suicide barrier

-

page 61

Freehand

Luciano Scherer

-

page 62

Further Reading

-

page 63

Next

Storage

-

page 64 - 69

THE SCENE AND THE PROTOCOL

Athens and the opportunity for new urban strategies

-

-

uncube's editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer (fh), Rob Wilson (rgw) and Fiona Shipwright (fs); editorial assistance: George Kafka (gk); graphic design: Lena Giovanazzi, graphic assistance Diana Portela and Janar Siniloo.

uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online portal covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

![]()

It’s All Souls’ Day, death is in the air, and we have decided not to dodge the issue. Indulge with uncube in some morbid sepulchral contemplation, from the pragmatics of cremation to the giddy imaginings of immortality and an architecture of the afterlife.

Back on earth, the architecture of death is not about withering and decay so much as living and building. It is about how we design, occupy and ritualise the structures intended to accommodate the last act in the hatch, match, dispatch trilogy of civic duty. It’s all about function – with just a little bit of legacy thrown in.

Si monumentum requiris circumspice

-

![]()

The strange ternary work of Argentina’s Francisco Salamone

Text by Rosario Talevi

Photography by Esteban Pastorino Díaz -

![]()

The close involvement of a state with the life of its citizens must inevitably entail a relationship with death. During the 1930s Francisco Salamone, state architect for Buenos Aires, turned this cycle of civic life, toil and death into remarkable concrete reality, with a programme of monumental municipal architecture that attempted to bring new life to 25 towns in the Pampas. With his work largely overlooked until recently, Argentine architect and curator Rosario Talevi tells the story behind an oeuvre that quite literally demands to be remembered.

Previous page: Entrance to municipal cemetery, Saldungaray. This page: Slaughterhouse at Azul.

-

Between 1890 and 1930, the advent of European modernity heralded an array of strategies that established “the State” as its principal actor. In 1969, Italian architect and historian Manfredo Tafuri described this process of decentralisation of the individual as giving way to a new spatial and social order. It is precisely this new order that articulates the relationship between architecture and governance; between urban development and municipal politics.

In Argentina this repositioning of the State as executor took place later than in Europe. In the province of Buenos Aires, it occurred during the administration of Manuel Fresco, governor of the democratic conservative party from 1936-40, who developed an ambitious Plan of Municipal Works – similar to Roosevelt’s New Deal – that included the provision of buildings, public spaces and infrastructure.

![]()

Under this mandate, Francisco Salamone, an Italo-Argentinian architect-engineer, was the official planner and executive director of nearly a hundred public works that made concrete a vision for an urban programme that aimed to occupy the territory, decentralise the capital and modernise the landscape of The Pampas.

In a 2005, writing for Argentine newspaper Clarín, René Longoni, an architect and researcher from La Plata university, described the scheme as “the most important and the vastest attempt at urban and architectural innovation... in the Province of Buenos Aires”, in which Salamone had “followed a personal route that combined the orthodoxy of Beaux Arts with imagination let loose, the rigour of technique with inexhaustible inventiveness, the impressiveness of the monumental with limited resources, and the confessional with desacralisation of tradition”.

-

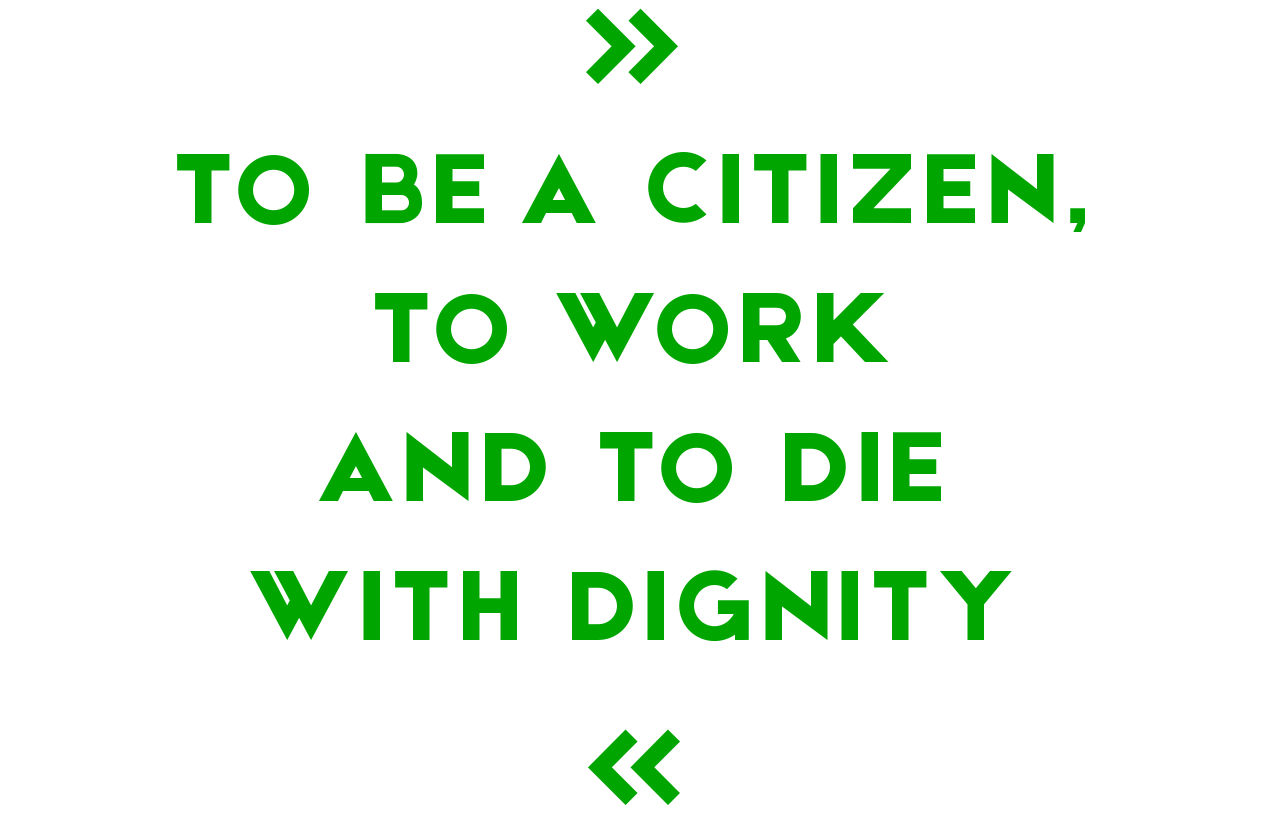

From 1936 to 1940 and across nearly 25 towns, Salamone established a programmatic series of 100 buildings that predominantly made use of three archetypes: the town hall (14 of them), the slaughterhouse (38) and the cemetery (8). A classic ternary order: beginning, middle and end, but a trilogy that would also rule the life of modern man: to be a citizen, to work and to die with dignity.

In Argentina at the time, this trinity was already in evidence thanks to the state and urban man’s conquest over the countryside (reflecting the role of the town hall); agricultural exports from the Pampa regions as the primary commodity underpinning the Argentine economy (the slaughterhouse) and the places that, in ancient times, man had treated as sacred spaces, monuments whose purpose was to commemorate (the cemetery).

Slaughterhouse in Carhué.

-

The sheer monumentality of Salamone’s buildings provides a disturbing contrast with the expanse of the surrounding plains. Salamone’s style, which might initially be attributed to the Art Deco movement or perhaps Italian futurism, has a strong expression of regionalism marked by the use of local materials: stonework from the surrounding quarries, for example. The eclecticism of the work has challenged the architectural community’s lexicon, which has variously described his edifices as “schizophrenic proclamations of the future” (Jorge Francisco Liernur, 2002) or “a scream to the landscape” (Jorge Ramos, 1991), “Populist Futurism” (Mario Sabugo, 2006) or, simply: “Salamonic Architecture” (René Longoni, 2001).

-

![]()

![]()

A rectilinear angel greets mourners to the Azul cemetery.

-

Well aware of the propagandist function of his work in furthering the aims of the State against the political backdrop of Argentina’s turbulent “Infamous Decade”, Salamone deliberately designed buildings that preach. Their message is conveyed allegorically, through the use of elements that possess a strong semantic content, for example the startling knife-shaped form on the slaughterhouse at Azul or the phrase which dominates the façade of the Carhue town hall, which shouts: “The Future is Today”.

Nevertheless, the prosperous future that these buildings so keenly aspired to, turned out to be ill-fated and both Salamone’s monumental ensembles and the provincial towns they so grandiosely adorned were largely forgotten.

For years, Salamone’s works have been slowly deteriorating and dying. At the end of the 1990s, the American art critic Ed Shaw, supported by Micky Wolfson, an American philanthropist and collector of propaganda art, set about bringing them back to life.

“The Future is Today” reads the sign above the entrance to the Carhué town hall.

-

Esteban Pastorino Díaz (* 1972, Buenos Aires, Argentina) graduated in 1993 with a Mechanical Technician degree, but after studying mechanical engineering for three years, he changed course and made his long-time passion for photography into a full-time career. As a partially self-taught photographer, Pastorino began his career exhibiting different bodies of work which exhibited a strong influence from his technical background. He has received numerous prizes, including the Abraham Haber Award for Photographer of the Year (Argentina Association of Art Critics) and has exhibited internationally. His work is held in numerous collections including the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art, Buenos Aires.

Rosario Talevi is an architect and curator. A graduate of the public University in Buenos Aires, she investigated design strategies and spatial practices that have been transforming Berlin’s undervalued, transitional and forgotten spaces at the Technical University Berlin before acting as Associate Curator and Editorial Coordinator for Make City: A Festival for Architecture and Urban Alternatives. She is currently researching and teaching at the Institute for Architecture at the Technical University Berlin.

Shaw, together with a group of enthusiastic architects created an archive of photographs. Until then, such a record had been non-existent: there is almost no surviving documentation of Salamone’s work. The images, which were exhibited in Buenos Aires for the first time in 1997 as part of the Buenos Aires International Architecture Biennial, led to an outbreak of Salamonic fever amongst academics and architecture fanatics seeking some sort of heritage recognition for Salamone’s built works.

“Memento Mei”, “Remember me!” demands Salamone’s work from the depths of the Argentine Pampas, ever-hopeful of being salvaged from the periphery, rising from the dead and being acknowledged at last as a remarkable piece of architectural heritage. I

Entrance to the cemetery in Salliqueló.

![]()

-

“How nice it would be to die swimming towards the sun,” Le Corbusier has been quoted as saying – and in a death seemingly as stage-managed as his life, it appears he perhaps did just that when out for his regular morning swim off Cap Martin on the Côte d’Azur, early on August 27, 1965.

More likely, one suspects, he died staring covetously back at the coast to Eileen Grey’s elegant modernist villa E1027 for which he had long held an obsession, and adjacent to which he had built his own tiny holiday home, Le Cabanon.

After his death, his body was conducted for a rather gothic State funeral to Paris, during which his coffin was processed through the courtyard of the Louvre, accompanied by soldiers with flaming tapers. Later his remains were returned for burial back to this modest plot facing the sea above Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, alongside those of his wife, Yvonne. He designed the grave for her and ready for himself, when she died in 1957.

The grave sits at the edge of the cemetery looking out towards the horizon, the line of which is echoed by that between his yellow-and-red plaque above and her blue plaque below – he definitively the sun, she the sea. I (rgw)

A Tomb with A View

“How nice it would be to die swimming towards the sun,” Le Corbusier has been quoted as saying – and in a death seemingly as stage-managed as his life, it appears he perhaps did just that when out for his regular morning swim off Cap Martin on the Côte d’Azur, early on August 27, 1965.

But more likely one suspects, he died staring covetously back at the coast to Eileen Grey’s elegant modernist villa E1027 for which he had long held an obsession, and adjacent to which he had built his own tiny holiday home, Le Cabanon.Photo: Barbara Burg + Oliver Schuh,

-

![]()

![]()

Añorbe Cemetery

ExtensionLocation: Añorbe, Spain

Architect: MRM Arquitectos

Date: 2011 -

MRM Arquitectos specialise in architecture, urbanism, interiors and landscape design. Founded in 2005 in Pamplona, it also has offices in Santiago de Compostela and Zaragoza. Projects include a health centre, kindergarten and music school in Palma de Mallorca, Spain and a new town hall in Santa Marinella, Rome.

mrmarquitectos.com

Form follows nature at the municipal cemetery of Añorbe, a small town in the Navarra region of Northern Spain. More landscape design than architectural presence, the new extension to the original cemetery by Pamplona-based MRM Arquitectos is planned with great sensitivity to its surroundings. Indeed the extension’s walls are actually inserted into the hillside on which it sits.

Beyond topography, the dusty tones of the hillside’s dry flora are matched by the untreated concrete blocks of the site’s walls – described by the architects as “built bare bones” – whose large perforations afford generous views out to the undulating Navarra landscape. The idea is that these openings in the walls will become overgrown in time, pulling the structure even closer into the bosom of the hillside.

Progression of use and the idea of bedding down in the landscape is the key to the Añorbe Cemetery’s design. Its austere walls and empty niches will gain purpose, taking people’s remains as the cemetery fills up, while nature will fill the site with life once again. I (gk)Photos: Mikel Muruzabal.

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

Funerary Shelter

Location: Pardesiya, Israel

Architect: Ron Shenkin Studio

Date: 2015 -

The Ron Shenkin architecture and design studio is located in Ein-vered, a small village on the outskirts of Tel-Aviv, Israel. The studio deals with architecture, art and what lies between. Other projects include the Ein-vered house, adapted from an abandoned storage building (2014) and a group of holiday bungalows in Dor, Israel (2015).

ron-shenkin.com

One of the central features of Jewish funerals is the eulogy – hesped in Hebrew – during which a speaker calls attention to the achievements of the deceased and implores the living to take stock of their lives. Tradition dictates that the hesped should offer praise, but not excessive veneration, for the deceased; a sentiment reflected fittingly in the eye-catching yet restrained articulation of this new purpose-built funerary shelter.

Designed by Ron Shenkin Studio, the shelter provides a space for mourners to conduct eulogies under its jaggedly folded concrete canopy, sited amongst the surrounding burial lots. The striking silhouette of the shelter is offset by minimalist structural support and quiet details – such as leaf-prints in the concrete floor, referencing the area’s earlier orchards razed for development.

The canopy provides a flexible space: able to accommodate large groups under its 256 square metre surface area, while smaller groups can hold more intimate ceremonies beneath its lower sections.

There is much debate among Jewish theologians over the intended beneficiary of the hesped: do we eulogise for the benefit of the dead or the living? In this shelter, Ron Shenkin neatly captures the middle ground of the argument. Celebratory but respectful, the structure calls for both vibrancy in life and quiet reflection in death. I (gk)All photos: Shai Epstein, courtesy Ron Shenkin Studio.

-

According to Zoroastrian tradition, since death is considered to result from the act of the evil spirit Ahriman, dead bodies are believed to be impure. Thus, in order to avoid contaminating the sacred basic elements of earth, water and fire, corpses are laid out in the sun to be consumed by carrion birds in a process known as excarnation. The structures built for this process have been referred to by a number of different names over the centuries, including dagdah, doongerwadi, or Towers of Silence. They represent a specific architectural type designed for death from one of the world’s oldest religions.

Typically, a tower of silence (the oldest of which date from the ninth century) is a circular structure, constructed solidly from materials such as stone, and it is usually located on a hilltop at a carefully calculated distance from the nearest settlement, though urban expansion has since seen some end up in close proximity. The roof consists of three rings circulating around a central well, where the ossuary is located. The outer ring is where male bodies are placed, the middle ring for female bodies and the smaller, inner ring designated for those of children. Once the bodies have been picked clean of flesh, the bones are placed in the well, which is channelled to four deeper wells where the last remains can decompose completely leaving no trace behind of the “unclean” body. p (Sara Faezypour)

Towers of Silence

According to Zoroastrian tradition, since death is considered to result from the act of the evil spirit Ahriman, dead bodies are believed to be impure. Thus, in order to avoid contaminating the sacred basic elements of earth, water and fire, corpses are laid out in the sun to be consumed by carrion birds in a process known as excarnation. The structures built for this process to take place are called dagdah, doongerwadi, or Towers of Silence. They represent a specific architectural type designed for death from one of the world’s oldest religions.

Image courtesy Alinari Archives, Florence.

-

![]()

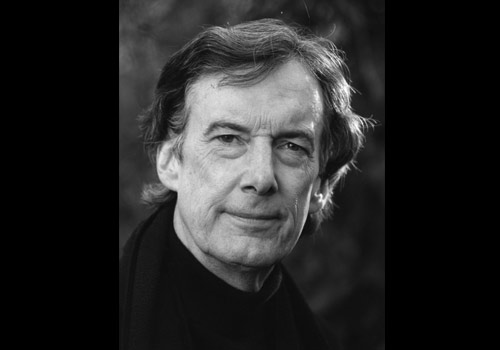

An interview with Charles Jencks, architecture theorist, landscape architect and

co-founder of the Maggie’s CentresBy Rob Wilson

-

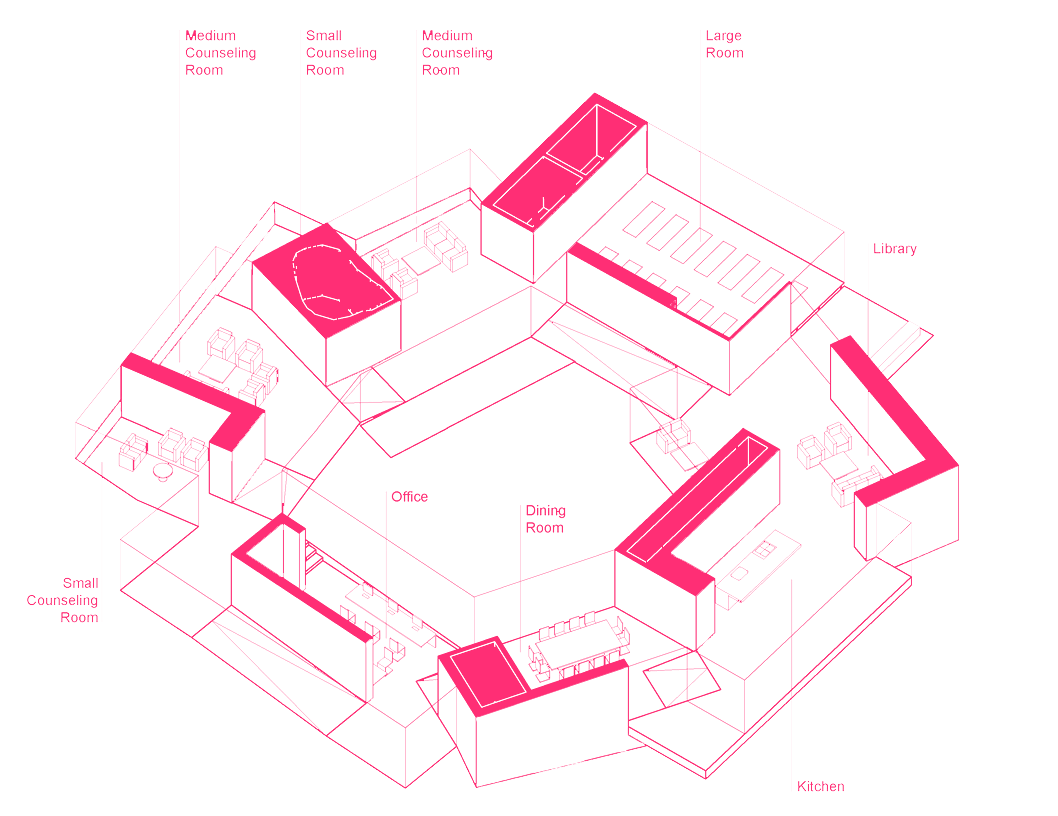

In counterpoint to the theme of this issue, Maggie’s Cancer Caring Centres are very much about living and providing hope, albeit set against the threat of illness and mortality. Landscape architect and architecture critic Charles Jencks founded the original centre with his wife Maggie, diagnosed herself with cancer in 1993, as a drop-in centre for support and respite for cancer sufferers. Both believed in the uplifting power of architecture. Maggie died in 1995, but since then twenty centres have been built around the UK and designed by architects such as OMA, Zaha Hadid, Ted Cullinan, Frank Gehry and Piers Gough. Charles Jencks, the original polemicist of pomo, talks candidly to uncube’s Rob Wilson about life, death, hope and what architecture has to do with it.

Previous page: Render of proposed Maggie’s Centre in Southampton by Amanda Levete Archirects. (Image: AL_A); This page: Maggie's Centre Nottingham, designed by Piers Gough. (Photo: Russ Hamer/Wikimedia Commons,CC BY-SA 3.0)

-

![]()

Can you explain the background to the Maggie’s Centres?

The thing is with Maggie’s is that we are not a hospice, our strapline is: living with and beyond cancer. It’s probably fair to say that people who come to us know that it is a question of life or death. But we don’t focus on the end of life per se. We are part of a new movement worldwide including hospices – and the amazing shift of the mass, factory hospital, towards a more personalised and enjoyable place to be. And we are now living so much more time with and beyond cancer. The average survival time is ten years after diagnosis. It was five years when Maggie my wife died in the 1990s.

I understand it was Maggie, who through her own battle with cancer, had the idea for the original Maggie’s Centre?

“The Big ‘C’”, as Maggie called it, is a death sentence and that is what she got in no uncertain terms in 1993. It’s a horrible thing to be given and you prepare for death. Maggie herself did, she literally got thinner, smaller, whiter, and more ashen and curled up to die as I have described in my book The Architecture of Hope: Maggie’s Cancer Caring Centres.

But at a certain point she decided “no, I need to go down fighting if I’m going to die”. Yet she said that the hardest thing of all was to decide to fight, because then you can fail, and if you fail, you fail big. Whereas if you’re prepared for death then you can prepare for it physically: at your job, with your family. It is in a way easier to take. Whereas if you go out fighting there’s risk involved, and with it hope.

Hope is not like optimism, which, as an attitude based on intellect or reasoning, has a much thinner orientation. Hope in contrast is a psychological, spiritual and physical thing that I compare to the metaphor of the horizon – because it's a projection forward into the future.

And as an architect you capture the horizon – the far off – you project yourself out into the future. The medical profession is future-orientated in that way too. Doctors and architects have a lot in common, because they deal professionally with hope for the future.

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

Interior of OMA’s Centre, Glasgow, UK. (Photo: Philippe Ruault); Plan of the OMA design. (Courtesy OMA)

-

I understand that there is a standard brief for a Centre that each architect receives?

It’s from a blueprint that Maggie herself researched and wrote up, before she died – it gave a real focus at the end of her life to do that. Of course we tell our architects, as if we needed to, that we’re about friendliness, homeliness and domesticity, we have to welcome people in. That is our basic job.

But how do you write this orientation of hope – this metaphor of the horizon – into the brief for the architecture?

You want an architecture that can perform this metaphorically, as future orientation, to the horizon, or using the metaphor of nature. There are many metaphors of hope. But the architecture also has to perform practically, to house a whole lot of things. At Maggie’s we do a thousand things, because if you have cancer, you have a thousand things to do. How, if I want a loan, do I tell the bank manager I have cancer? What do I do if my hair falls out from chemotherapy? Where do I get a wig? So hope comes in little tiny practical packages as well as one big metaphorical one.

So the architecture needs to contain different types of spaces and places where people can meet, individually or communally?

One of the things that makes it easier for the architects is that the brief is already written. But they have to interpret it. It is interesting that they’ve produced twenty very different centres. Typologically even, as well as organisationally and metaphorically. Yet they’re all from the same brief. I sometimes contrast this with say a franchise like McDonalds or indeed the Cistercian churches of the 1140s which were all laid out exactly on St Bernard’s instructions. With Maggie’s every centre is different. And that is partly because of our principle that the architects interpret the site, the culture, the meaning, all the rest of it, themselves.

So a bit like postmodernism compared with the universal, one-size-fits-all of modernism?

Yes. In postmodernism the basic idea is not only that of mass-customisation but also the belief that there really are different scientific solutions to the same problem. Whereas Le Corbusier always believed, as modernism always believed, that there was one best solution. An optimum one, if only you could find it.

-

Still I hadn’t thought that the solutions for the Maggie’s Centres would be so different. But Rem had, because Rem researched it – all the typologies of the previous ones. He then proposed a doughnut shape for OMA’s Maggie’s Centre in Glasgow – like a calculated new move in chess.

And in the last five years they’ve reverted to being more like disappearing icons, in reaction against the icon idea, so much so that Amanda Levete’s new scheme in Southampton has disappeared to the extent that we cannot find it! She’s managed to talk the hospital into turning the car park into a forest and then designed this disappearing building.

But doesn’t each Centre have an iconic role too?

Well, all our buildings are sort of little tiny icons. But I feel that they justify the notion of the iconic building because they are about death, about final things, as well as about hope, deep psychological, spiritual and social. By using anti-symbolic symbolism, they have a very strong emotional charge. Yet it’s very important that we’re hybrid. We are a church that’s not a church, a house that’s not a home, an institution that’s not a hospital, an art gallery that’s not a museum. We’re all these building types and yet we are none of them. And we’ve got to provide a really friendly easy to like place, where you know where the front door is, a place that you feel is homely, familiar.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Maggie’s Highlands, designed by Page\Park Architects. (Photos: Keith Hunter)

-

Just looking at your own landscape architecture practice – there’s a lot of symbolism. Do you see this same balance of the physical and the metaphorical things going on?

Yes I am slightly more polemical in what I do with my work, which takes metaphors of the universe and nature. I try to find what is a visual equivalent for all those retrograde metaphors and reductivist notions – such as Richard Dawkins’ Selfish Gene etc. – which I am critical of – and then design from it. So it’s explorative.

One of the problems I have is that we live in a time of a breakdown of religion, a breakdown of culture, of all the meta-narratives. It’s a culture where clients are completely confused about iconography. They just want escape, to have something immersive – I really can’t hear that word again!

While some of your schemes echo prehistoric forms and standing stones, I know you very much identify with the cosmic rather than the prehistoric per se. I wondered therefore how you view the famous statement of Adolf Loos that: “Only a small part of architecture belongs to art: the tomb and the monument”. This is the sort of opposite, endgame, backward-looking way of thinking in how “the beyond” is signified in architecture.

Well while there’s a lot of historical truth to that statement, the problem is that it is basically not true. Loos wanted his architecture to look like it had been there forever, sort of ageless. He even made his houses into monumental tombs. I understand where he was coming from philosophically.

I can see the tomb and the monument wanting to be abstract, eternal. But if I were to design a cemetery. I wouldn’t do what Aldo Rossi did at his great San Cataldo cemetery. I would try to bring in life. It’s really important to get out of just the tomb and the monument and into life. So it is not about an end but transcendence. I am much more hopeful. If you go back to prehistory to see how these sites like Stonehenge and Woodhenge were used: they were fantastically communal theatrical, celebratory spaces – as well as to do with final things.![]()

Plan for Maggie’s Centre Highlands. (Image courtesy Page\Park Architects)

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Frank Gehry's characteristic metal folds adorn the roof of the Maggie's Centre in Dundee. (Photo courtesy Maggie's); The interior of the Snøhetta designed Maggie's Centre in Aberdeen. (Photo: Neil Gordon); The concrete outershell of the Snøhetta designed Maggie's Centre in Aberdeen. (Photo courtesy Snøhetta)

-

Charles Jencks is a world renowned cultural theorist, landscape designer, architectural critic and historian, and co-founder of the Maggie’s Cancer Care Centres.His best-known book is The Language of Post-Modern Architecture first published in 1977, re-issued as The New Paradigm in Architecture in 2002.

With his late wife Maggie Keswick, he co-founded the Maggie’s Cancer Care Centres which provide free practical, emotional and social support to people with cancer and their families. Since 1996, twenty centres have been built by distinguished architects, with two awarded the Stirling Prize for Architecture. The Maggie's Centres were the subject of his book The Architecture of Hope, recently revised and rewritten for the second edition (Frances Lincoln, 2015).

His celebrated design for his own garden in Scotland is the subject of his book The Garden of Cosmic Speculation (Frances Lincoln, 2003) and he has subsequently worked on landscape design projects in Europe, including an iconographic and green project for CERN, as well as projects in China, Turkey and South Korea.

His most recent project The Crawick Multiverse, was commissioned by the Duke of Buccleuch, and opened in Scotland in June 2015.

That reminds me of Le Corbusier talking about his first visit to New York in his book When the Cathedrals were White, describing the “funereal spirit…of Caravaggio and Surrealism” of skyscraper lobbies and comparing this to the incredible everday life and activity that animated mediaeval cathedrals in Europe.

Le Corbusier’s spirit was incredibly right. I have learned more from Le Corbusier than almost anyone else. He was always trying to give a spiritual message and that is why he had such a profound effect on architecture. All of the great architects who mesmerise people have a spiritual message. He was trying, as I’m trying, to work out how you can transform symbols and bring them alive.

His work is incredibly powerful, emotionally, spiritually. You know he had a tuning fork to the universe. I mean look at Ronchamp, you cannot beat it for this. He is always interesting, however wrong he was in terms of his universalising ideas on modernism.

You famously dated the death of modernism to the demolition of the Pruitt Igoe housing estate in St Louis in 1973. How do you view the strong fascination today with modernist housing estates or brutalist urban schemes, as if they are fragments from some utopian past, before the fall?

Well I think it’s mainly because many people have died, I mean the survivors of the 60s and 70s still don’t think it was ever utopian. So it can look quite beautiful and wonderful to a new generation. It’s a useable past, the problem is that not only is it nostalgic but it is not an educated response. Firstly, architects have always been utopians. But the danger is also that it becomes seen as the architecture of good intentions, to paraphrase Colin Rowe’s famous title. The good intentions often mask ideology and bad motives. It is delivery we want.

And they didn’t deliver, they failed?

Yes. They were ideological rather then real. I have always used Karl Marx’s definition of ideology, which is quite apt here: specifically professional ideology which is held by a profession in order to make more work for itself. That is very strong with architects, with doctors and particularly with lawyers and politicians – if you look at who uses hope the most. Napoleon said, politicians are specialists in hope. They know that it’s their currency. So they devalue it. But it’s still real. You can’t kill hope – even politicians can’t!

And I get that from one of the great books coming out of the Holocaust by Victor Frankl: Man’s Search for Meaning, in which he looks at how the ability to hope helped some to survive longer in the concentration camps. And it is very apt for me in relation to the Maggie Centres. Because it’s odd, hope comes in many different ways almost like a visitation or grace – it arrives typically in a social intercourse, just parachutes in. Frankl emphasises this social collective, interactive nature of hope. And that’s what Maggie Centres can provide so effectively. p

![]()

-

For 87 years the London Necropolis & National Mausoleum Company operated one train daily. The 11:35 service ran from Westminster Bridge Road station in the City to Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey – via Necropolis Junction – and its passenger load was London’s recently deceased.

The line’s first train set off in 1854, at a time when London was facing a crisis of overcrowding in cemeteries. Brookwood and the Necropolis Railway provided an innovative solution to the crowding by transporting corpses out of the city and into its rural surroundings along a dedicated line.

This image is of the railway’s second station, next to Waterloo, which was opened in 1902 and designed by Cyril Bazett Tubbs. The building, in a marked departure from the gloom of orthodox funereal architecture, exhibited an up-to-date metropolitan opulence.

First-class mourners were escorted into the station along a corridor of glazed white bricks, lined with palm and bay trees and could take an elevator to the platform. Third-class passengers meanwhile used a secondary entrance, were greeted with sparse decoration, and had to take the stairs. p (gk)

![]()

For 87 years the London Necropolis & National Mausoleum Company operated one train daily. The 11:35 service ran from Westminster Bridge Road station in the City to Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey – via Necropolis Junction – and its passenger load was London’s recently deceased.![]()

![]()

![]()

Image courtesy National Railway Museum / Science & Society Picture Library.

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Alberto Galardi: Marxer Pharmaceutical Laboratory, Loranzè, Italien, 1959–1962

Fotos: © Paolo MazzoPhoto: © Paolo Mazzo

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

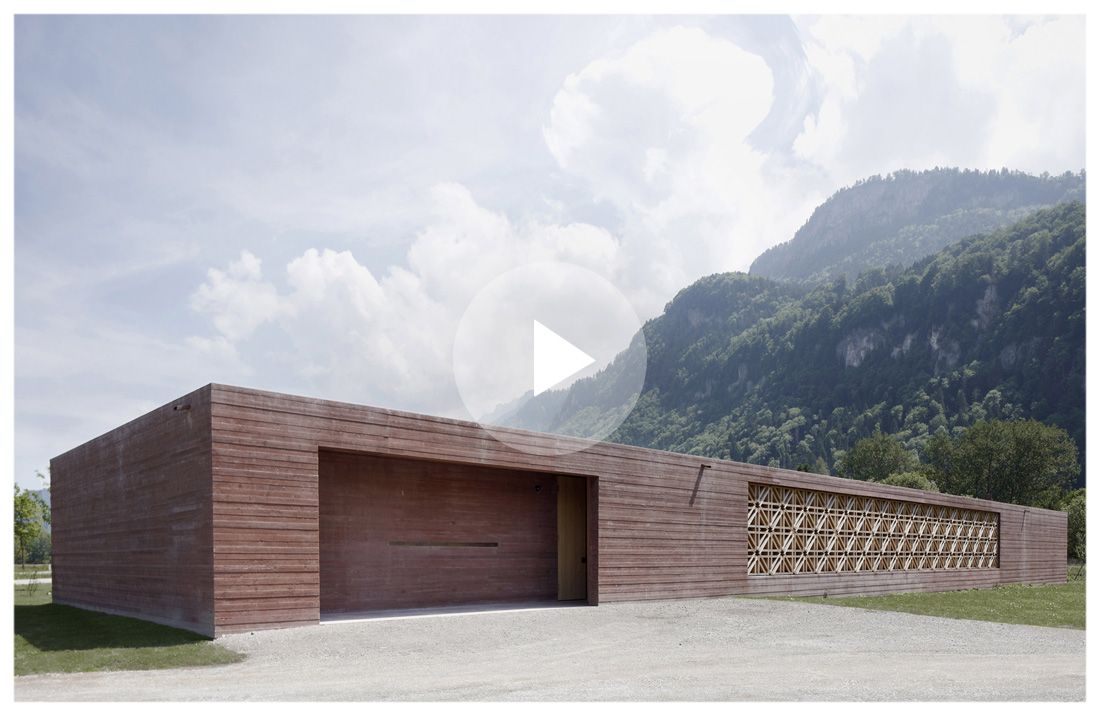

Islamic Cemetery, Altach

Location: Vorarlberg, Austria

Architect: Bernardo Bader Architekten

Date: 2012Photo: Adolf Bereuter, courtesy Bernardo Bader Architekten.

-

Bernardo Bader set up his office in Dornbin, Austria in 2003 after studying architecture at the University of Innsbruck. Bernardo Bader Architekten have completed numerous residences across Austria and are currently working on a cultural centre and mosque in Heilbronn, Germany. In 2013 Bader received the Aga Khan Award, rewarding excellence in architecture that addresses the needs of Islamic societies, for the Islamic Cemetery in Altach.

bernardobader.com

This project in the far-western Austrian town of Altach, is the country’s first-ever Islamic cemetery. Despite a steadily growing number of Muslim citizens over the past decades, the country previously had no dedicated place to bury them according to their religious beliefs once they died. The bereaved’s only choice was between a funeral without Islamic rites, followed by interment in a special part of a Christian cemetery, or transporting the remains of their loved-ones back to their country of origin – somewhere they might have left many decades before.

It wasn’t until 2003 that the Islamic communities and immigrant associations joined forces to begin planning for a dedicated Islamic cemetery. In September 2007 an architectural competition was held and won by Austrian architect Bernardo Bader. His design, consisting of a one-storey complex on an 8,500 square metre plot, holds some 700 graves. Largely made of red, fair-faced concrete and oak, this cemetery complex is as distinctly modern as it is discreet and contained. A quiet place without grand gestures, the Altach Cemetery demonstrates that tradition and the contemporary can look beautiful together – even in the face of death. I (fh)![]()

![]()

Artist Azra Akšamija’s qibla wall. (Photo: Marc Lins); video courtesy Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

-

![]()

![]()

Architectures of the Afterlife

By Herbert Wright

![]()

Etching of Jacob’s Ladder from the original Luther Bible, ca. 1574-80.

-

Herbert Wright looks at some of the weird and wonderful architectures and structures – described or visualised by prophets, writers, artists, poets and filmmakers – with which we have tried over the centuries to picture what – if anything – comes next, after we shuffle off this mortal coil.

![]()

“Skyladder” by Cai Guo-Qiang, 2015. (Photo: Lin Yi, courtesy Cai Studio)

![]()

-

If we re-awaken after we die, what shall we see? If the afterlife brings us to some alternative para-reality, then what of its architecture? Architects have long designed for death with mausoleums and cemeteries, but these are earthly constructions. Admittedly, some tombs have in-built provisions for the afterlife. In Ancient Egypt, for example, it was common to be buried with possessions from one’s Earthly life, but also – in the case of pharaohs – with a boat to navigate the river and twelve gates of the underworld that needed to be passed through. Mexican drug lords similarly tend to stock their ornate mausoleums with luxuries, as if they expect to re-awaken to a high-life after death. But to find a structure that actually leaves this life for what’s beyond is another speculative matter entirely.

Stairway to Heaven

Jacob’s Ladder is perhaps a good starting point. The Old Testament book of Genesis says the ladder to Heaven came to Jacob in a dream. That’s also where the great Gothic cathedrals of Europe later aspired to reach, with their soaring stonework and the very shape of their upward-pointing arches. The last such English cathedral, Bath Abbey (rebuilt from 1500), goes further – on either side of the entrance are stone ladders, like great vertical louvred strips, with statues of angels climbing them. It was the Bishop, Oliver King’s dreams made solid.

Bath was also where Chinese artist Cai Guo Qiang first tried to realise his own heavenward dream in 1994, with his work Sky Ladder, in which a hot air balloon was used to pull up 500 metres of ladder. Wind defeated him. In 2001, he was set to repeat his attempt in Los Angeles, but then all flights were grounded after 9/11. It was only in in June 2015 that he finally succeeded, in his hometown of Quanzhou, with fireworks lighting up his Sky Ladder in the early morning twilight.

William Blake transitioned the ladder into a Stairway to Heaven, in his watercolour Jacob’s Dream (circa 1800). Peopled by women, some with angel wings, it twists towards a heavenly radiance, like the passage towards light that people recall seeing in near-death experiences. That brings us to A Matter Of Life and Death, the 1946 British film in which a downed airman, played by David Niven, finds himself on the Stairway To Heaven (the film’s title in the USA, although directors Powell and Pressburger actually denied any direct heavenly reference).In the film, this stairway has become an ascending escalator, flanked on one side by massive statues of historical figures, the only spatial markers along its seemingly infinite length.

Artist David McKraken’s Diminish and Ascend (2013), on the other hand, comes to a pointy end. The installation at Bondi Beach, Sydney strips back the staircase to a minimum (with Heaven indeed potentially accessible should one overstep its last tread). -

![]()

“Diminish and Ascend” by David McCracken. (Photo: David McCracken)

-

Cloud Nine

The popular idea of Heaven floating on clouds, is something still echoed in structures from Tomás Saraceno’s Cloud City and Tiago Barros Studio’s Passing Cloud (both 2011) and even in NASA’s HAVOC mission visualisation, suspended high above the Hell of Venus’ blistering 462°C surface. Heaven’s clouds, however, support God’s throne, quintessentially portrayed by Victorian artist John Martin in his epic series of paintings Heaven and Hell from the 1850s.

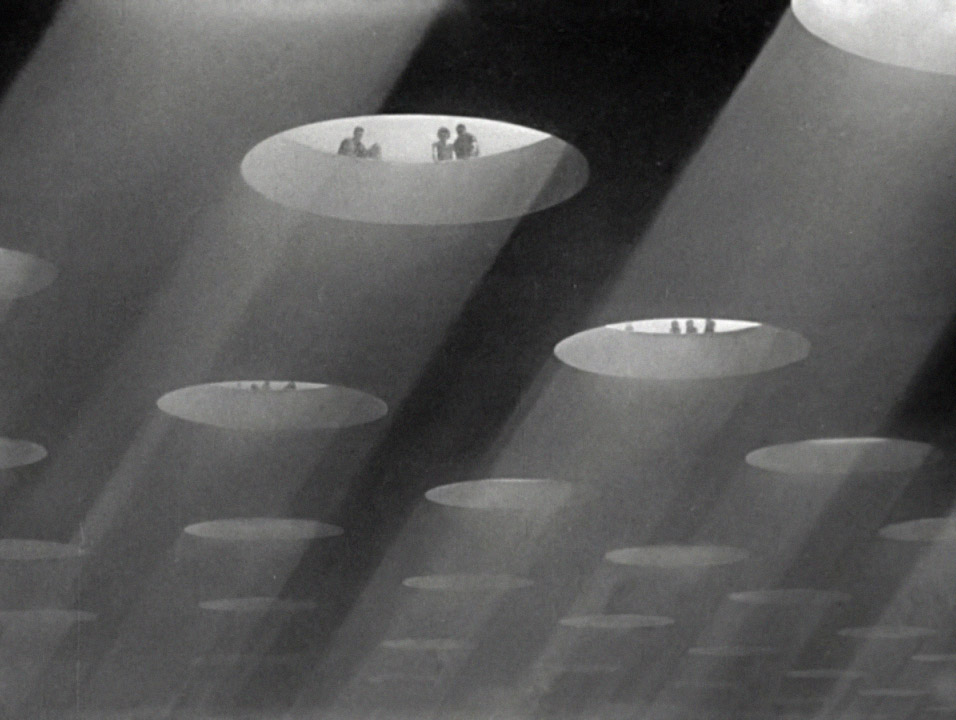

Martin had more heavenly detail to offer in other works. In The Courts of God (1825), beyond a vast rectangular lake bounded by colonnades of Egyptian columns, gleams a great neo-classical citadel of domes and towers (and in one version, a minaret). A Matter of Life and Death meanwhile gives Heaven a distinctly modernist update, particularly with its view from beneath a plane perforated with great circles through which people look down into the darkness (not unlike SANAA’s Rolex Learning Center in Lausanne).

Both those visions portray a place of judgement, which might end with a one-way ticket to the other place, usually located underground. In Wilfred Owen’s First World War poem Strange Meeting (1918) he meets a soldier he has killed. The location is “down some profound dull tunnel, long since scooped/ Through granites which titanic wars had groined”, where “no blood reached there from the upper ground/ And no guns thumped, or down the flues made moan”. He recognised it as Hell.“The Courts of God” by John Martin. (Image courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

-

Going Underground

The subterranean structure of Hell is described by Dante in his Inferno, written 700 years ago. Dante is guided by the poet Virgil down through the Nine Circles of Hell, implying detail about its architecture. This has provided a blueprint for Hell to be visualised, from Botticelli’s 1480s map to Infografika’s contemporary colourful schematic in which the journey starts at a metro stop rather than “a dark wood”.

We even have the equivalent of a rendering of the Sixth Circle’s City of Dis in Stradano (Jan van der Straet)’s late sixteenth century drawing (along with a fine series of pictures of the miserable souls down there). Another Flemish master, Hieronymous Bosch – and his many followers – produced some of the best-known represents of Hell in paint, like Christ’s Descent into Hell painted by an anonymous follower in the 1560s. It’s a fiery place dotted with Flemish buildings, and a variation on one of Bosch’s great organic architectural innovations: a face as inhabitable structure.

“Christ’s Descent into Hell” in the style of Hieronymous Bosch (ca. 1550-60).

-

Herbert Wright is an architectural journalist and historian, author and art critic based in London.

herbertwright.co.uk

![]()

Soul Limbo

Dante’s deepest level was not fiery, but an icy place where Satan is bound. And his first circle was Limbo. Contemporary limbos are often the familiar world, with the architecture the same and the afterlife seemingly real but unresolved and strange, as in the TV drama Life On Mars or Jens Lien’s film The Bothersome Man (2006).

The Irish writer Brian O’Nolan, under nom-de-plume Flann O’Brien, sets his Third Policeman (1940) in a surrealistic rural Ireland, and has an interesting architectural offering: a police station that is almost impossible to find, because it is hidden within the walls of a house that appears quite ordinary both inside and out.

But from Limbo, there may be escape to another afterlife. In Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), the astronaut Bowman is placed in the limbo of a simulated hotel room, before ultimate rebirth as a Star-Child.The set, designed by John Barry, is a hotel room with faux-baroque panelling and furniture, and a luminous gridded floor. Here the ultimate architect is represented by the presence in the room of the black monolith. Time jumps in silence here. You are helpless. Perhaps, if Heaven and its eternity exists, it is like this... without any follow-up. I

Screenshot from “A Matter of Life and Death” (1946). (Source)

-

In 1936 a sheltered and frustrated middle-aged divorcée from Chicago rather unexpectedly inherited the family fortune. Denied both school and university as a child by her parents (because she was a girl), she always wanted to do something with her life “of significant value to the community”, but it was not charity work she had in mind. Instead, Frances Glessner Lee, in best Miss Marple manner, became nothing less than “the mother of forensic investigation”.

Inspired by a Boston medical examiner, George Burgess Magrath, who had complained to her of how murder investigations were often botched and ruined by inadequately trained detectives and coroners alike, Lee funded a Library of Legal Medicine at Harvard and the country’s first forensic pathology programme as well as becoming an expert in the field herself. She also created a series of miniature (1:12 scale) crime scenes by hand, with obsessive attention to detail, in order to test crime scene investigators’ powers of observation. Called the “Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death”, the 18 models she made in the 1940s are used to this day as teaching aids in the Maryland Medical Examiners’ office in Baltimore. I (sl)For more on the amazing Miss Lee and images of her mini crime scenes see our blog article Deathly Details and accompanying photographs from her biographer, the artist and photographer Corinne May Botz.

Murder Most Marple

In 1936 a sheltered and frustrated middle-aged divorcée from Chicago rather unexpectedly inherited the family fortune. Denied both school and university by her parents as a child (because she was a girl), she always wanted to do something with her life “of significant value to the community”, but it was not charity work she had in mind. Instead, Frances Glessner Lee, in best Miss Marple manner, became nothing less than “the mother of forensic investigation”.

Photo: Corinne May Botz

-

![]()

![]()

The New

CrematoriumLocation: Stockholm, Sweden

Architect: Johan Celsing Arkitektor

Date: 2013 -

In bridging the gap between life and that which lies beyond, crematoria must serve not only as a place where bodies are stored, but also disposed of. Somewhere in between they must also play host to the necessary ritual and ceremony for the bereaved, all the while ensuring none of these steps appear to overlap with one another.

The simply-named New Crematorium, located just outside Stockholm, entailed a further demand for its designers, Johan Celsing Arkitektor, namely that it integrate seamlessly into the surroundings of Eric Gunnar Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz’s 1940 Woodland Cemetery, widely viewed as a pinnacle of twentieth century cemetery design and now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Hence the title of the initial proposal: “A Stone in the Forest”.Reflecting the idea that death is merely the companion (rather than the opposite) to life, the notion of “bridging” permeates the design of this single-storey structure: the brick exterior has been carefully chosen to match the colour of the surrounding tree bark, convincingly linking built environment to that of the natural. This connection with the landscape is maintained inside, with large windows offering open views out into the forest and skylights that allow the play of light and shadow onto the white concrete interior. Eschewing the theatrical trappings of many traditional funeral buildings, the architects chose to leave the walls largely untreated throughout both the chapel and cremation areas; linking the two instead. This offers an honest indication – though more gentle hint than blunt reminder – of what has to happen here.

![]()

All photos: Ioana Marinescu.

-

Johan Celsing was born in Stockholm, Sweden in 1955. A graduate of the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm in 1981, he first worked in the offices of Carl Nyrén and Bengt Lindroos in the same city, before establishing his own office Johan Celsing Arkitektor in 1985. In 1993 the practice completed its first built work, the Nobel Forum in Stockholm and since then has continued to produce architecture which is in keeping with the principles of “the robust and the sincere”, frequently placing traditional Swedish materials within a contemporary context. The practice has offices in Malmö and Stockholm. In 2015 The New Crematorium at the Woodland Cemetery received a nomination for the Mies van der Rohe European Union Prize for contemporary architecture.

Continuing this honest approach, whilst referencing the act of procession – a key element in the architecture of death for centuries – careful consideration has also been given to the entrance area to the crematorium: for few moments in life can be as jarring as that of arrival at a funeral. The approach leads onwards but also upwards, a gentle ascent that not only prepares mourners, but also reflects the whole site’s concern with the inevitability of this journey, yet one – hopefully – to something higher. I (fs)

-

The Palace of Failed Optimism is an inverted pyramid, a modular, ever-expandable (fictional) megastructure to store all the big-but-failed architectural utopias of the past, present and future.

A tomb, designed by WAI Think Tank, as a giant and growing monument to ideas and ideals that never came true: “a palace for the Malevichs and the Tatlins, for the Moses and the Wrights, for the Le Corbusiers and the Hilberseimers, for the Haussmans and the Cerdas, for the Khidekels and the Chernikovs […], but also for the Speers and the Iofans, for all the dream-makers and the nightmare enforcers, for the geodesic domes and the walled cities, for those who dream of anthropological transformations and radical new beginnings.” WAI are deliberately enigmatic on the function of their “palace”; is it a museum for everyone to visit, or a well-secured prison to store away these dangerous, radical or occasionally poisonous ideas? p (fh)

Where Ideas Go to Die

The Palace of Failed Optimism is an inverted pyramid, a modular, ever-expandable (fictional) megastructure to store all the big-but-failed architectural utopias of the past, present and future.

Image courtesy WAI Think Tank

-

![]()

An architectural battle with entropy

By Léopold Lambert

-

Shusaku Arakawa (1936-2010) and Madeline Gins (1941-2014) were an artist/architect couple who founded the Reversible Destiny Foundation in 1987, dedicated to the construction of architecture to extend the human lifespan. Léopold Lambert visited their Mitaka Reversible Destiny Lofts in Tokyo; a building that provides different uses for each individual according to their physical abilities – allowing users to achieve what they may previously have considered impossible.

![]()

![]()

![]()

All photos: Masataka Nakona, unless otherwise stated.

-

We Have Decided Not to Die stated Shusaku Arakawa and Madeline Gins in the title of their 1997 exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum SoHo in New York. It was an affirmation of ambition for their architecture of “Reversible Destiny”, to act as an instrument for bodies not to die. Since Arakawa and Gins have both since passed on, in 2010 and 2014 respectively, many cynics have pointed to the irony of this artist/architect duo’s ambition. But this is a misinterpretation. For what the cynics do not understand about their work is that not dying is not the same as acquiring immortality.

-

Arakawa and Gins’ approach raises questions about what we call “life” and what we call “death”. Our common understanding sets them in opposition as periods of time (i.e. someone, who used to be alive is now dead). However, Arakawa and Gins and their Reversible Destiny Foundation saw life and death as forces, operating within a mode of thinking that echoed the French eighteenth century physiologist Xavier Bichat. He was the first to define life as “the set of functions which resist death”, thus envisioning life and death as two opposing energies, one constructive, one entropic. This entropic force – we might call it ageing – is precisely what Arakawa and Gins’ architecture attempted to resist. Each component of their built environments was designed to combat entropy, in a call to “reinvent our species through works of procedural architecture”.

-

Arakawa and Gins’ Reversible Destiny Foundation has designed many projects over the last two decades, five of which have been realised. These include the Ubiquitous Site (1994) in Nagi, Japan, where only gravity dictates what separates the walls from the floors and the Bioscleave House (2008) in Long Island, USA, which incorporates one of the most radical floors in the history of interior living space.

But it is the Mitaka Reversible Destiny Lofts (2005) in Tokyo, which are particularly interesting. This is a collective housing block where inhabitants experience Arakawa and Gins’ architecturally induced philosophy on a daily basis.![]()

Background image: Bioscleave House. (Photo: Dimitris Yeros); Insert: Ubiquitous Site, Nagi. (Courtesy of Arakawa + Gins)

-

![]()

-

Léopold Lambert is a Paris-based architect and editor-in-chief of The Funambulist Magazine, its blog and its podcast, Archipelago. He is the author of Weaponized Architecture: The Impossibility of Innocence (dpr-barcelona, 2012), Topie Impitoyable: The Corporeal Politics of the Cloth, the Wall, and the Street (punctum, forthcoming 2015) and Politique du Bulldozer (B2, forthcoming 2015).

leopoldlambert.net

The uneven floors, for example, invite bodies to always be acutely aware of their positioning; there is a carefully calibrated spectrum of colours corresponding to physiological research on their impact on the human brain; there are the hooks in the ceilings allowing for most of the furniture to be hung up and maximise the potentiality of indoor activities, and the inclusion of spherical rooms in all the apartments negating the categorisation of space into “walls”, “floors” or “ceilings”.

Beyond the apparent biological agenda of these lofts, there is also a political one. In contrast to the overwhelming majority of architectures, the Reversible Destiny projects are not designed around a normative body, usually characterised by a standard able-bodied male, sometimes paired with the gendered idea of a female counterpart. Many architects would agree with the idea that a body can only be termed “disabled” relative to any given environment, but how many fully explore this relationship and challenge it in their own architecture?

The Mitaka Lofts are dedicated to the author and activist Helen Keller (1880-1968), whose physical relationship to the normative built environment was characterised by her deaf-blindness. In fact, one of the first assignments during the workshops organised in the Lofts was for bodies to experience the spaces whilst blindfolded. Vision was not a banned sense for Arakawa and Gins; yet, they believed, its overuse relative to other senses reveals here again a normative interpretation of the world.

Momoyo Homma, the director of the Japanese branch of the Reversible Destiny Foundation, told me that her mother, who normally requires a cane to walk, does not need one when she walks in the Mitaka Lofts.Despite the evocative name chosen by Arakawa and Gins for their foundation, we do not have to perceive this phenomenon necessarily as a reversion of the ageing process, but rather as a telling example of the normative straightjacket that the standard built environment surrounds us with. The Mitaka Reversible Destiny Lofts do not destroy the notion of norms; yet they do embody one of the rare architectures that has generated the means to mitigate the violence of its own presence. I

-

The Black Cat (1934) was the first-ever horror movie to pair the two masters of the macabre: Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff. It was also the first one ever to feature a modernist architect as the monster. Instead of the usual crumbling gothic pile, the villain of this piece inhabits a modernist house of glass and steel with a great curving chrome-railed staircase.

This is the house of Hjalmar Poelzig [sic] (Boris Karloff), an Austrian architect-cum-psychopath, who of course has designed the house himself. It was built on the ruins of an old fort, which coincidentally Poelzig commanded himself during WWI. In the movie, Poelzig is accused of having betrayed the fort under his command causing the death of thousands of Austro-Hungarian soldiers who now lie buried around the house. On top of this, Poelzig’s bizarre taste in decoration takes the form of dead women stacked in glass coffins. Things get really weird when his black cat is killed only to reappear the next morning as if nothing has happened... before, during the film’s climax (spoiler alert), the house gets blown up. For full effect we highly recommend you take a look at this architecture-horror-classic for yourselves. I (fh)

Modernist Monsters

The Black Cat (1934) was the first-ever horror movie to pair the two masters of the macabre: Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff. Directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, it was also the first film ever to feature a modern architect as the monster. Instead of the usual crumbling gothic pile, the villain of this piece inhabits a modernist house of glass and steel with a great curving chrome-railed staircase.

Image © NBCUniversal

-

![]()

Leon Berger’s Southampton Crematorium

By Owen Hatherley

Photography by Greg Moss

-

Owen Hatherley investigates the municipal afterlife facilities in his home city of Southampton, a place where many aspects of civic life – and death – are still architecturally micromanaged by the legacy of the 1960s City Architect, Leon Berger.

-

Nearly every funeral I’ve ever been to has taken place in the municipal crematorium of Southampton, a medium-sized port on the south coast of England, the city where I grew up. Southampton Crematorium was designed in the late 1960s by the City Architect, Leon Berger (1908-81), in the days when almost every aspect of urban life was being provided for by the City Architects Department. The two parks that I most liked to play in as a child, Riverside Park and Mayflower Park, were both laid out by Berger’s department on odd bits of disused industrial land. They’d built ten or so housing estates, which ranged from melodramatic clusters of towers commanding views over the sea at Weston Shore, to the wan garden suburb at Millbrook. They’d designed the secondary school I went to, the doctors’ surgeries and the polytechnic, and they’d added public walkways across the medieval walls.

![]()

They’d also designed a snazzy concrete park bench, which was and is marketed worldwide as the “Southampton Bench”. Catering for every part of your life eventually meant, of course, catering for your death, and providing a cheap and unpretentious place for your lifeless remains to be incinerated.

Southampton Crematorium is in a secluded place on the northern edges of the city, where the dense, wild Southampton Common spreads itself out and starts to become actual countryside, or at least until the M27 spoils the illusion. In fact, the crematorium is conveniently just off the motorway, like a Little Chef service station café. But when you get there, the illusion of being secluded by woodlands is rather convincing. -

![]()

-

I′ve never been there in anything other than autumn or winter, so it is fixed for me as a place of damp leaves, bare trees, fog. Car parks are set around two “chapels”, although the services can be as secular as you want them to be. Each chapel is a large, rectangular volume, each clad in copper.

The style of these heavy volumes, sheathed in sheets of green-gold-black metal, is similar to some more celebrated buildings that are contemporary with them, such as the churches of Gillespie, Kidd & Coia or, closer to home, Basil Spence’s Nuffield Theatre at the University of Southampton. It’s a way of suggesting the richness of traditional church materials without actually using them or copying them, but in this verdant setting, it gives the effect of organic things rotting, left to decay.Between these asymmetrically proportioned chapels are the two crematorium chimneys, a functional necessity, which can be covered up if you’re feeling shy about the building’s function, but here, the architects have refused to do so. They’re tall, square, and clad in yellow stock brick. Below, some ivy has grown across the low entrance pavilions.

It’s the interior where the real harshness of the building is apparent. I am an advocate of the Southampton City Council Architects Department. I once dedicated a book to them. I think their work, at its best (the Northam Estate, just off the river Itchen, for instance), is among the most sensitive and intelligent housing built in Britain after the Second World War. It is light, clever, optimistic and airy architecture, reflecting Berger’s training as an enthusiastic young modernist in 1930s Liverpool. So I’m disposed to appreciate this work. The minimalism of the crematorium, though, is extreme, however much it might seem like a pretty normal, standard municipal product.Although the building is totally non-denominational – you can cremate and “celebrate the life of” anyone from any faith here – it’s hard to imagine a building more Protestant. No frills, no nonsense, not even a little reassuring stained glass, as you might find in more famous modernist crematoria by Basil Spence (Mortonhall, Edinburgh) or Maxwell Fry (Coychurch, Bridgend). Bare brick, bare wood, bare concrete.

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

Owen Hatherley is a writer and journalist based in London who writes on architecture, politics and culture. His first book Militant Modernism (Zero Books, 2009), was a defense of the modernist movement, reclaiming its revolutionary credentials. Subsequent books have included A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain (Verso, 2010), Uncommon (Zero, 2011), a book on the pop group Pulp, A New Kind of Bleak (Verso, 2012), and Across the Plaza (Strelka, 2012). His most recent book is: Landscapes of Communism: A History Through Buildings, published in June 2015 by Allen Lane. He writes regularly for Architects’ Journal, the Architectural Review, Icon, the Guardian and New Humanist, and has authored several blogs including Sit down man, you’re a bloody tragedy (2005-2010).

In a church, this sort of Protestantism serves a symbolic role – there is no mediator, nothing between you and the word, separating you from God. If you’re having a “humanist” ceremony here, it signifies something else. There’s nothing. That’s it. No dressing up, not even any consolation.

The City Architects Department went round the city opening up its historic monuments to the public, building sunnily confident housing, schooling its working-class children, doing their level best to give people a better life. For the end of those lives, all that optimism disappears, leaving nothing much more than a blank wall to cry against.

![]()

-

After 78 years and more than 1,600 deaths, it seems that action is finally being taken to help reduce the grisly suicide rate at San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. A proposed suicide barrier has been the subject of heated debate ever since it was initially put forward in 2006, with some critics suggesting it threatens the architectural character of the suspension bridge, constructed in 1933. Others have argued that the money required to construct the barrier (a steely 76 million USD) would be better spent providing mental health care to those in need. But meanwhile people just keep jumping.

The proposed design is a long, stainless steel mesh that will span the length of the bridge on both sides, twenty feet beneath the pedestrian walkways, extending 20 feet out from it (and painted in International Orange, of course). The barrier is not designed to provide a gentle landing. Those who do jump into the net are expected to suffer the same injuries one might sustain from falling two stories onto a steel platform – acting as both deterrent and incapacitator for help to then arrive. p (gk)

(David Corby/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Saving Us From Ourselves

After 78 years and more than 1,600 deaths, it seems that action is finally being taken to help reduce the grisly suicide rate at San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. A proposed suicide barrier has been the subject of heated debate ever since it was initially put forward in 2006, with some critics suggesting it threatens the architectural character of the suspension bridge, constructed in 1933. Others have argued that the money required to construct the barrier (a steely 76 million USD) would be better spent providing mental health care to those in need. But meanwhile people just keep jumping.

Photo (with render) courtesy of the Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. -

The creator of this issue’s cover is Luciano Scherer, a multimedia artist from Porto Alegre, Brazil. He works across a variety of media creating paintings, videos, installations and sculptures. The death and the uncanny are major themes in his work, as portrayed in his films, objects and installations. He sees the making of art as a confrontation of the unknown, of what causes fear, in order to transcend it.

This painting comes from a series which take a surrealistic approach to the theme of death. The series makes allusions to spirituality, religion, resurrection and alchemy. Scherer takes inspiration from the Brazilian tradition of naïve painters, as well as Boschian depictions of fantasy and death.

-

FURTHER READING

Blog LENS02 Nov 2015

Deadly Details

The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death

Blog Lens19 Nov 2015

A Concrete Garden

Carlo Scarpa’s Brion Tomb

Blog Viewpoint24 Nov 2015

Back To Life

Researching the Future of Death

Blog Building of the Week10 Nov 2015

The Evil Twin

Aldo Rossi and Gianni Braghieri’s San Cataldo Cemetery

Blog Building of the Week26 Jan 2015

Funeral for a Building

Leaving this world in a blaze of glory

Blog Building of the Week23 Nov 2015

A View to A Hill

Gubbio Cemetery Extension by Andrea Dragoni

Search our archive! -

Storage

Issue No. 39:

November 26th 2015Photos: Joel Tettamanti

-

The Scene and the Protocol

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»I don’t mistrust reality of which I hardly know anything. I just mistrust the picture of it that our senses deliver.«

Gerhard Richter

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents