-

Zaha Hadid’s Four Decades of Breaking the Box

by Aaron Betsky

-

Hadid’s architectural career has been a quest to translate the continual movement of her fluid forms into architecture, says Aaron Betsky, and in doing so she has changed the nature of the discipline.

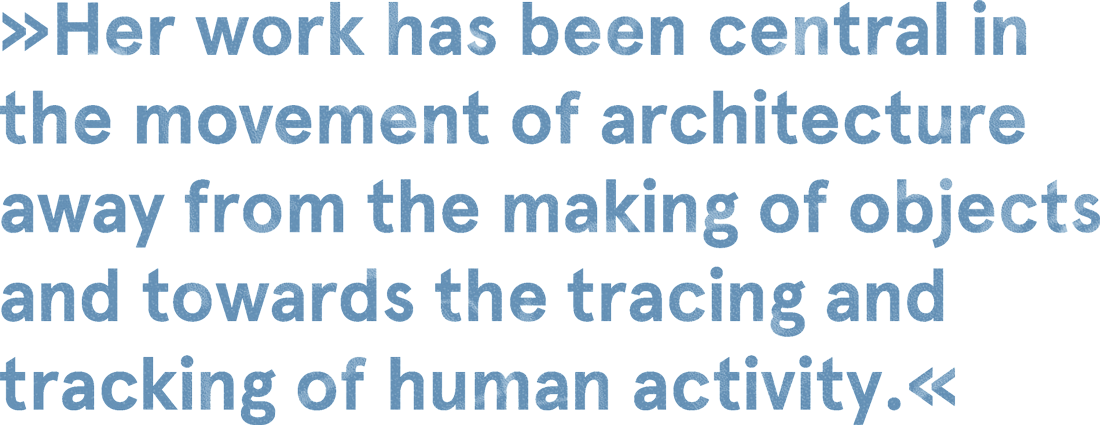

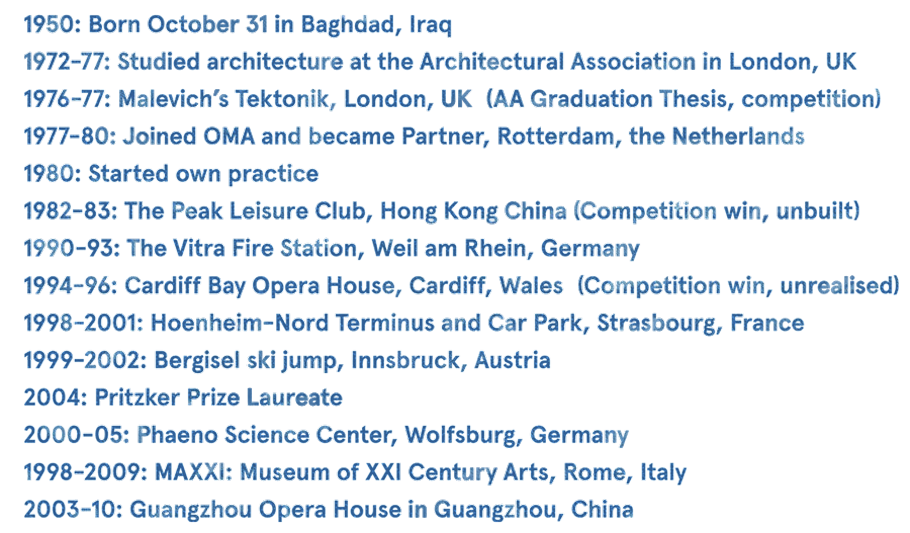

Zaha Hadid’s career in architecture has traversed the terrain of modernism from the retroactive activation of the Suprematist notion that we could defy gravity, coherence, and type by the dissolution of form, through the creation of fluid forms that slithered away from definition and closure, and then into the realm of parametric modelling that melds architecture, landscape, and human behaviour into forms that are even more elusive. As such, her work has been central in the movement of architecture away from the making of objects and towards the tracing and tracking of human activity, with the aim of creating a profound modelling of form around our social selves.

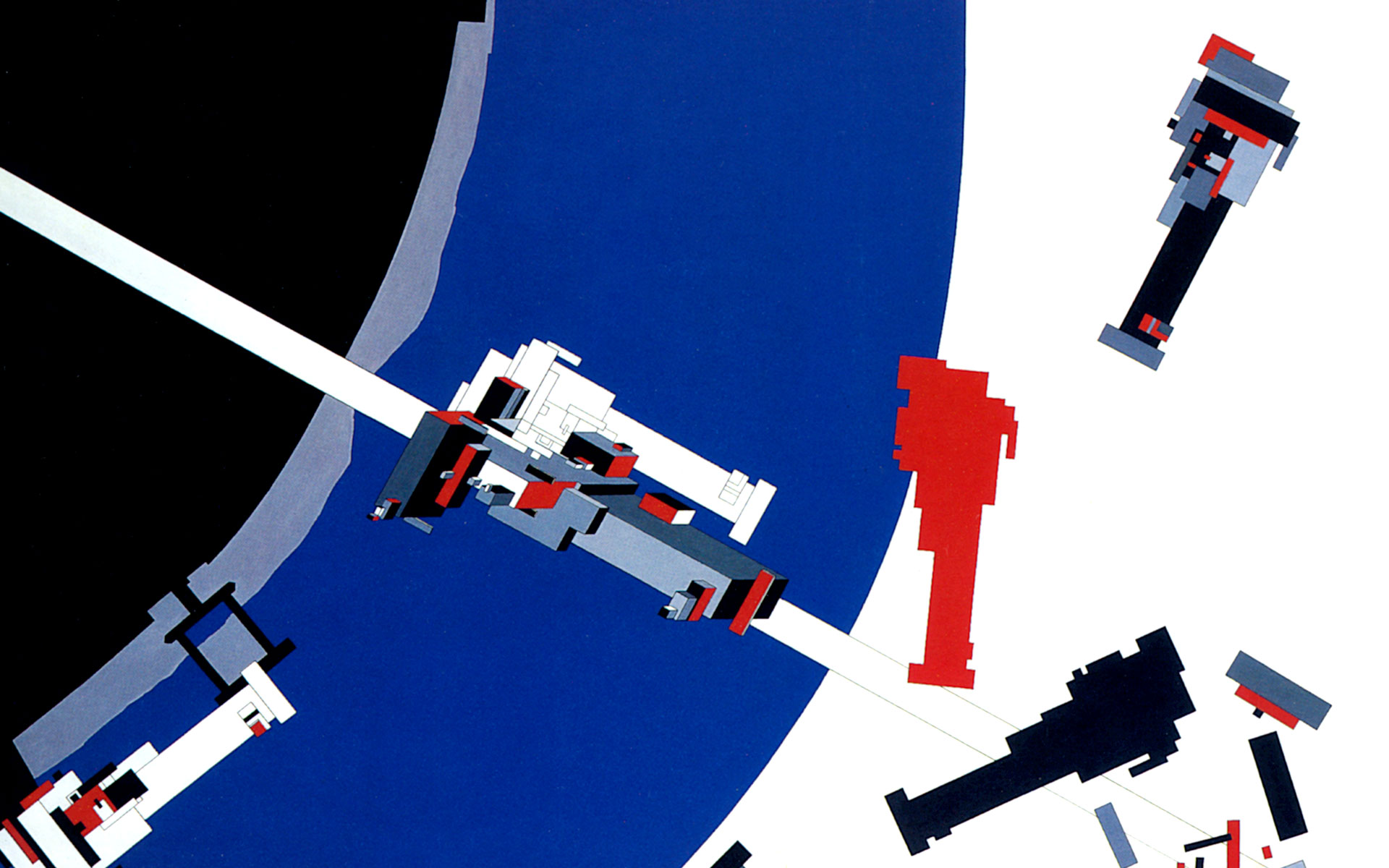

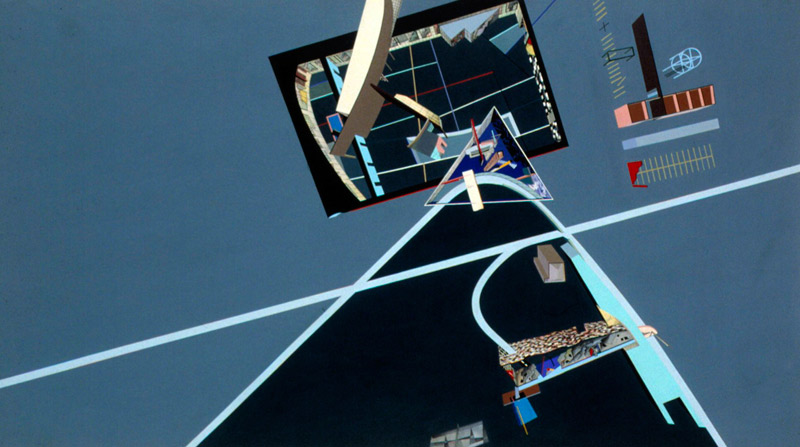

Previous page: painting from “Malevich’s Tektonik”, Zaha’s graduation thesis.

(All images courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects; collage by Lena Giovanazzi)

-

When Hadid first came on the scene, the battle waging about architecture, at least in academic circles, was still between whether the object should – as the so-called “greys”, such as Charles Moore and Michael Graves, thought – be defined by either the panoply of classical elements academic architects had recently rediscovered, or cloak itself in the familiarity of a vernacular; or – as the “whites” such as Peter Eisenman and Richard Meier, felt – be abstracted to the point of disappearance. Students and teachers at London’s Architecture Association (AA), many of whom – like Hadid – had became associated with the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, instead proposed blowing the object up. They saw architecture, pace Frank Lloyd Wright and the Russian architects of the post-Revolutionary period, as breaking open the box.

Dame Hadid broke the professional box as well, becoming the most prominent woman and only person of Arab descent to make a mark in architecture at the turn of the millennium. Although such a professional achievement might seem separate to her work, it’s been as important in changing the nature of the discipline as her built forms.

-

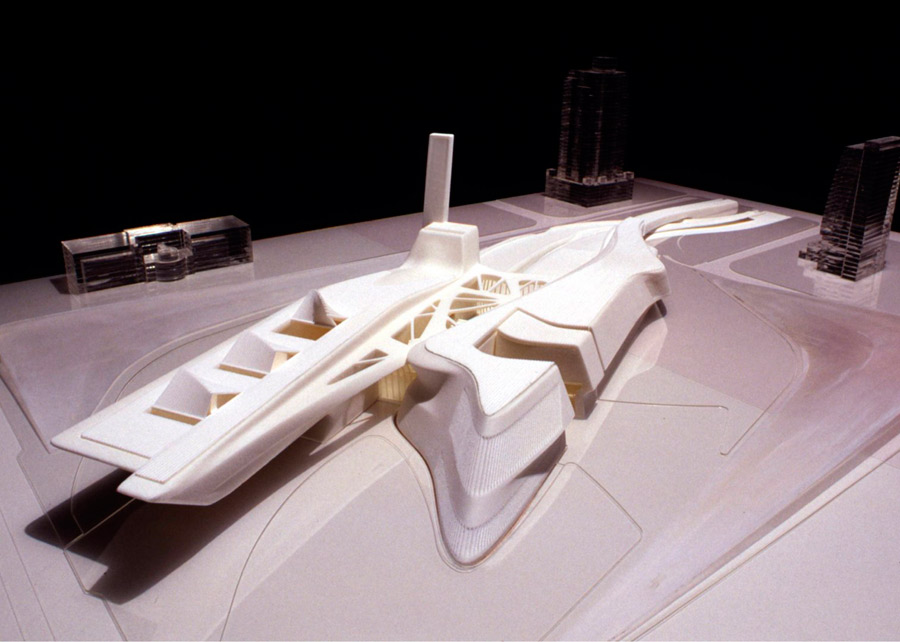

By the time Hadid had established her own office several years after graduating from the AA, she became one of the central figures in what critics such as Mark Wigley called “deconstructivism”: a more profound refusal to build coherence or, in some cases, even build at all, by architects who saw their work as a re- and misreading of the past, of physical context, and of the conventions of communication. Wigley canonised his interpretation of Hadid’s work in the exhibition Deconstructivist Architecture that he curated with Philip Johnson at MoMA in New York in 1988, and in which her work featured prominently.

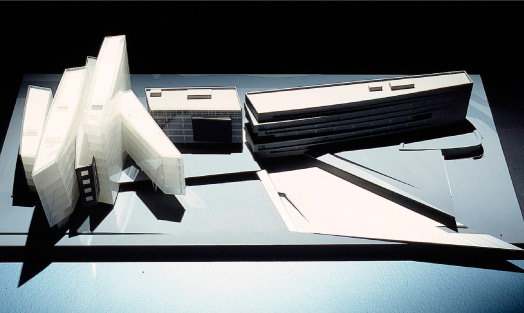

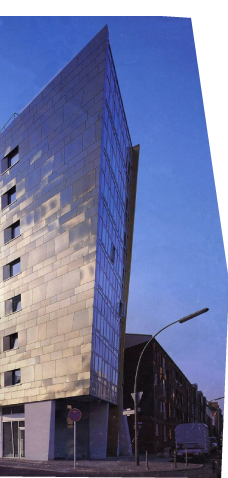

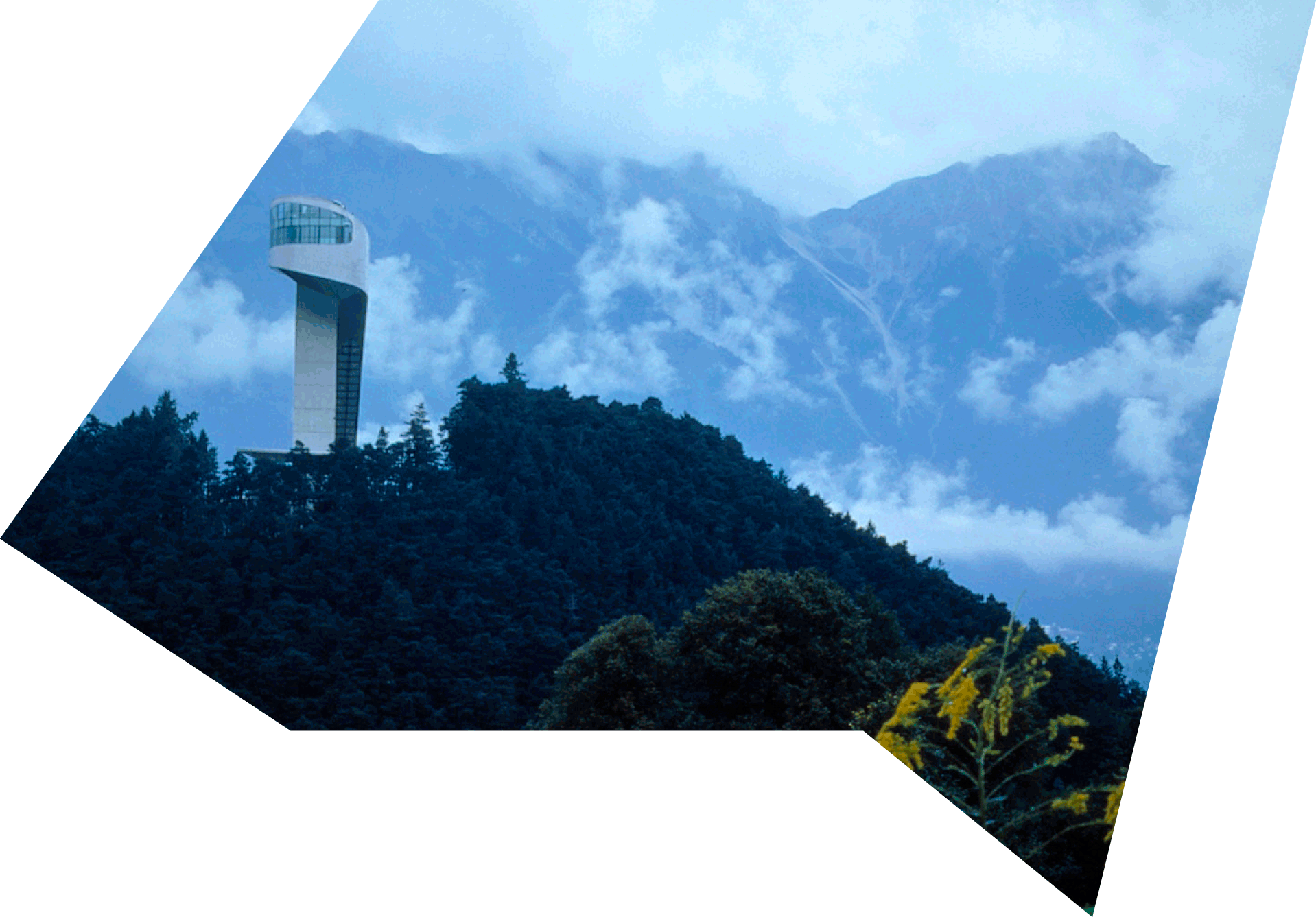

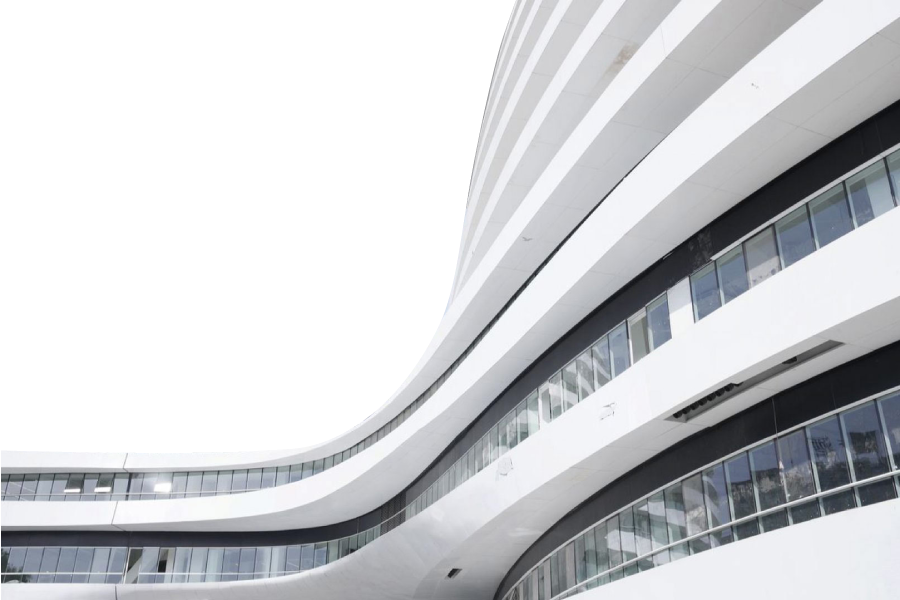

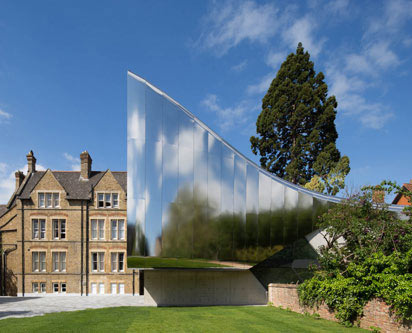

When Hadid finally began to build, first in Berlin and Weil-am-Rhein, then in Cincinnati, and soon around the world, she, like many of her fellow graduates of the late 1970s and early 1980s wars to resuscitate modernism, such as Wolf Prix of Coop Himmelb(l)au, Bernard Tschumi, and Daniel Libeskind, had to confront questions over how her theoretical and aesthetic position could be elaborated while creating objects that met functional, technical, and economic needs. Her answer was to propose spaces and forms that unfold in spiralling movements out of the landscape. The result, as Hadid saw it, would be continual movement in which the distinction between inside and outside, between public and private, and between enclosure and openness, would disappear.

The advent, during the mid 1990s, of sophisticated computer-aided visualisation and construction tools made the translation of this quest for fluid form into buildings, much more possible, although, at least until fairly recently, the construction of her firm’s designs have often acted more as promissory notes for such free-form design, as their construction has not always living up to the idea.

-

-

-

-

-

-

Aaron Betsky is a curator, critic and writer on architecture and design. In 2015 he became the new dean of the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, which has twin campuses at Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin and Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Betsky was born in Missoula, Montana, USA and grew up in The Netherlands. He graduated from Yale University with a BA in History, the Arts and Letters in 1979 and an M.Arch. in 1983. He then taught at the University of Cincinnati from 1983 to 1985 and worked as a designer for Frank Gehry and Hodgetts & Fung. From 1995 to 2001 Betsky was Curator of Architecture, Design and Digital Projects at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art before moving back to The Netherlands to become the director of the Netherlands Architecture Institute in Rotterdam (2001-2006). From 2006 to 2014, he was the director of the Cincinnati Art Museum, during which time, in 2008, he was also the director of the 11th Exhibition of the Venice Biennale of Architecture.

Betsky has written numerous monographs on the work of late 20th century architects, including I.M. Pei, UN Studio, Koning Eizenberg Architecture, Inc., Zaha Hadid and MVRDV, as well as treatises on aesthetics, psychology and human sexuality as they pertain to aspects of architecture, and is known for his key contribution to a spatial interpretation of Queer theory.

In last few years, Hadid and her office have shown themselves more than capable of creating exhilarating forms. Unlike the recent work of some other members of the generation shaped by the events of ’68, who have built up large building practices, she continues to create forms that are startling in their openness and radical in their formal expression.

Since the early 2000s, her work has also extended to the creation of objects and even fashion accessories. Rather than seeing these as afterthoughts to her build work, as most other architects do, they are part of her continual search to rethink the personal and the social body, in such a manner that design breaks down physical, political, sexual, and economic barriers.

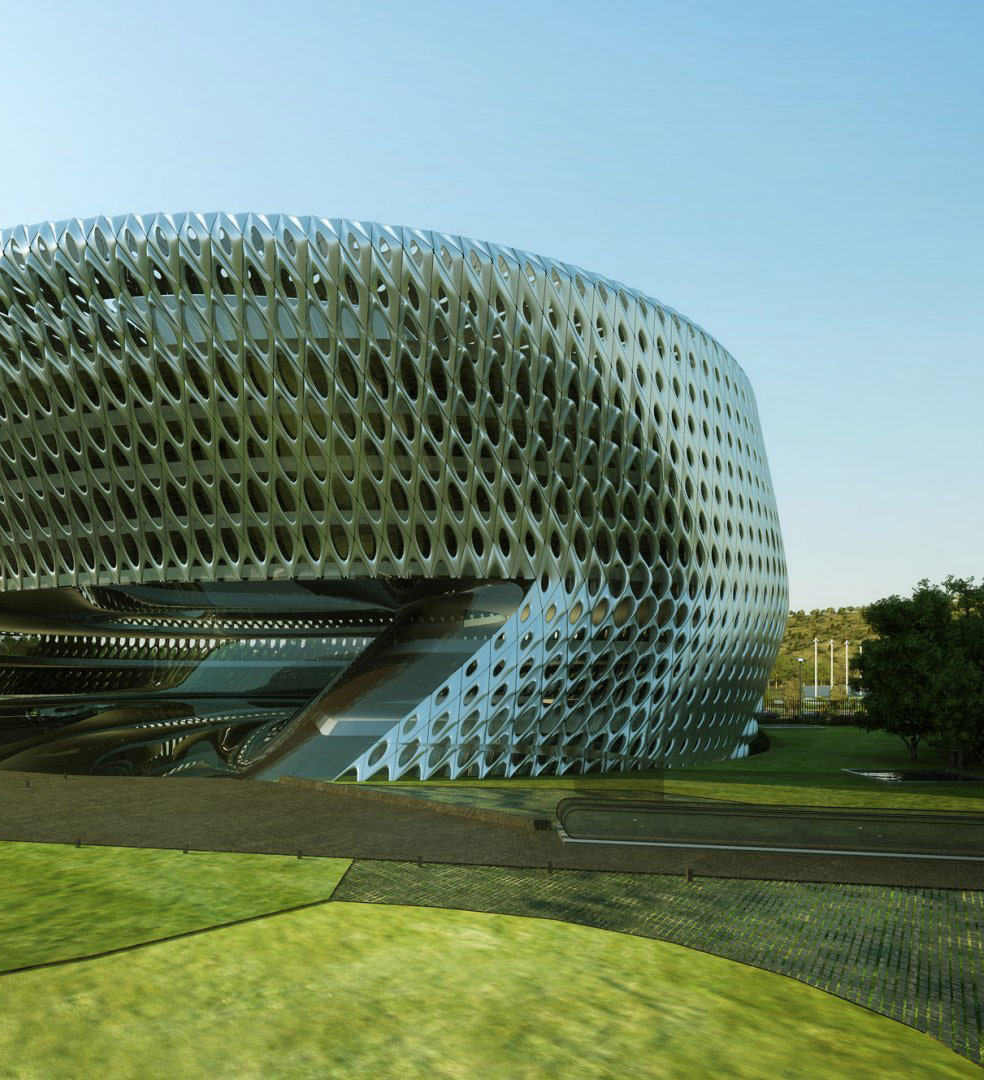

Most recently, her partner at Zaha Hadid Architects, Patrik Schumacher, has proposed that architecture can go even further in moulding itself to social movement by using the computer to model and predict this movement, with the intention of creating spaces and surfaces that allow for a variety of different activities. If the studio proves able to take this approach far enough, such an approach promises to allow for the creation of buildings whose adaptability to human action and social interaction would make their formal resolution appear not just the result of an aesthetic development from floating planes to snaking blobs, bulging prows, and Moebius-strips of space, but as the fulfillment of a desire to free architecture from its role as the built affirmation of the social, economic, political, and physical status quo.

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Form follows feminine.«

Oscar Niemeyer

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents