The ways in which design not only serves to distinguish products, but also fulfils basic necessities, is illustrated well in an exhibition currently showing at the Triennale in Milan. Made in Slums, curated by Fulvio Irace, shifts the coordinates of design focus onto a Nairobi shantytown where Western designers could learn a thing or two from the products made from waste with pragmatism, imagination and skill.

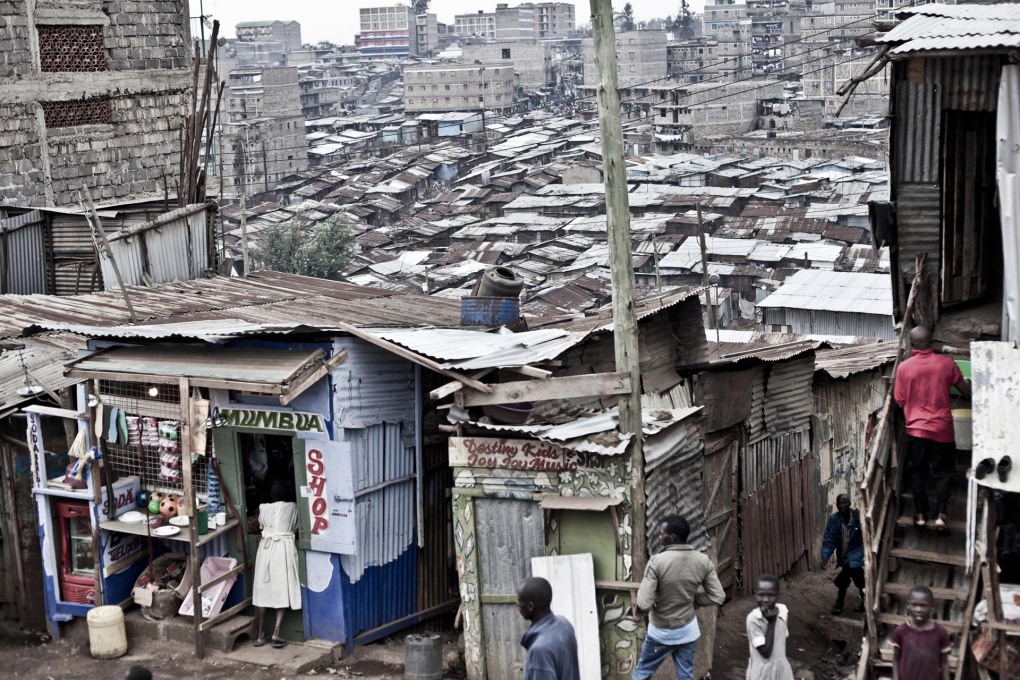

It is considered to be one of the toughest and most dangerous places on earth to live. Mathare, home to more than 500,000 people, is Nairobi’s second largest slum stretching one and a half kilometres along the river of the same name. When its unpaved roads become raging torrents during the rainy season, it is not unusual for both people and their dwellings to be washed away by the mud. There is no electricity or sewage system, let alone medical treatment facilities or enough schools. And despite the free primary school facilities that have been available for some time in Kenya, illiteracy is rife here. Mathare is an island, a community isolated within itself that few residents manage to escape.

Goods for Everyday Use

What does get into the slum is rubbish – mountains of it from the capital city just five kilometres away. Materials ranging from bits of wood to advertising signs, tin cans, gas bottles to bits of sheet-metal provide the basis and motor for an economy that goes far beyond waste separation and extracting raw materials. An enormous variety of goods for everyday use are created here with a mixture of pragmatism, imagination and skilled handcraft from these waste materials. The exhibition Made in Slums highlights some of these goods, highlighting how as objects they are well worth considering from a design perspective.

Although the show was initiated and coordinated by Flavio Irace, it was Francesco Faccin who originally researched and selected the objects. The Milan-based architect spent almost two years in Mathare constructing a school and vegetable garden for the residents whilst working with the non-profit organisation Liveinslums. Time enough for him to encounter and appraise the broad range of articles such as pots, mousetraps, shoes, spoons, ladles or lamps on offer on the streets and in the markets. “The products made in this slum have a mysterious strength about them that makes it hard to categorise them in time: they are contemporary beyond doubt and have an urban character, but at the same time they seem as traditional as the tribal structures that define the social texture of the slum”, explains Faccin.

Series Production by Hand

Although many of these products are made in series, their production is almost entirely by hand. Sheet metal, for example, is hammered against wooden forms until it takes on the shape of a frying pan. Matt aluminium sheeting, often used for cladding safari vehicles, serves as raw material for cooking pots with matching lids. The gas bottles used for cooking in wealthy districts are converted into robust stoves that can be fuelled with wood or coal. Even old tyres don’t get wasted, but are repurposed into sturdy sandals that even under close inspection give nothing away of their automobile origins. And the serially-produced toy digger trucks, painted in the local Tingatinga style, that are made from melted plastic poured into wood or aluminium moulds, have a market that reaches way beyond the borders of the slum.

The viewer’s contemplation of these objects in the exhibition is not detached from the circumstances of their production. Video interviews with inhabitants of Mathare show how they struggle not only with problems of hygiene and health, but crime as well. Whilst local gangs demand protection money, even the local police regularly demand money too from its inhabitants and one-man businesses, to such an extent that even a glimpse of someone in uniform is enough to set off a flight reflex. And because almost no one has a bank account, incomes are stored in “house banks”, metal boxes made from old tin cans, usually buried under the floor, which are all too easy for thieves to find.

Role Models

"In Mathare we encounter 'design without designers', comparable with the ‘architecture without architects’ described by Bernhard Rudofsky”, explains Fulvio Irace. Rudofsky organised the 1964 exhibition Architecture Without Architects in the New York MoMA and with it drew attention to forms of anonymous architecture built by non-specialists. Rather than dismissing the beauty of these so-called “primitive” buildings as coincidental, they were shown to result from the application of human ingenuity, applied to finding sensible solutions for specific needs and practical uses. The continuing currency of this position, even today, could be seen in the recent show Learning from Vernacular at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein. Here too mud, wood and grass constructions from developing countries were presented as inspirations for resource preserving and sustainable building in the West and elsewhere.

Of course whilst the Mathare products are exactly models for industrial wares in Europe or the USA, what is important is logic behind their making: only what is needed is produced from that which is available. These designs are not made with any one-upmanship between manufacturers in mind, they are just the practical basis for functional, long-lived, affordable and modest products. Here readymades are not an ironic statement, but are integrated into the everyday as practical and self-evident companions for life. A lesson that some western designers would do well to heed.

– Norman Kietzmann, uncube correspondent in Milan

(Translation: Sophie Lovell)

Made in Slums – Mathare Nairobi

until 8th December 2013

La Triennale di MilanoViale Alemagna, 6

20121 Milan