With its raw brick façades, the dnA house by BLAF architects stands out in the morass of denatured farmhouse and villa styles of Belgian suburbia. It is highly energy-efficient with airtight detailing and a separate interior timber shell, yet does not conform to the duff image so often associated with buildings that have the “sustainable” adage attached. But, Stefan Devoldere asks, is it more statement than real efficiency?

The dnA house sits on a typical street on the periphery of Brussels, dominated by detached single family houses, each in their own way the embodiment of an impossible dream of rural living. This is the stage-set of Belgian suburban life, where a lack of spatial policy has resulted in individual incarnations of the same consumerist ideal, or where commercial housing developers have perfected a sketch-up of farmhouse iconography as generic turnkey product. (uncube recommends checking out the site uglybelgianhouses to get a taste of some.)

This has been the breeding ground conversely for the hesitant, understated style that has dominated Belgium architectural practice for years, as if the only dignified thing to do in this cacophony of individual expression is to be utterly silent and humbly efficient.

More recently, housing developers have been turning to alternative, more contemporary typologies to spice up their catalogues, buying into the doctrine of sustainability — with recipes of low-energy and passive housing — to inject their outdated, out-rated typologies for serial housing production with new meaning and market value. Meanwhile a new generation of architectural offices has started to systematically question the underlying principles that produced this suburban landscape with housing projects that both embrace and defy the Belgian condition as a ground for experiment and innovation.

BLAF architects are an example of this tendency: a practice that challenges the common denominator of suburban architectural expression and its present moulding with sustainable building concepts. An earlier project, a few blocks away, was their zero-energy Textile House, which seemed to contradict everything most people thought a zero-energy house should look like. With its outspoken architectural style the house proved that sustainable need not automatically mean dull. It claimed prizes and praise for both its style and sustainability and effectively kick-started the practice. Since then, BLAF has learned the ropes of low-energy, tested a range of building techniques, and perfected the art of airtight detailing. This mastery of passive building concepts has meant they now have leeway for variations, improvisation and educated hunches.

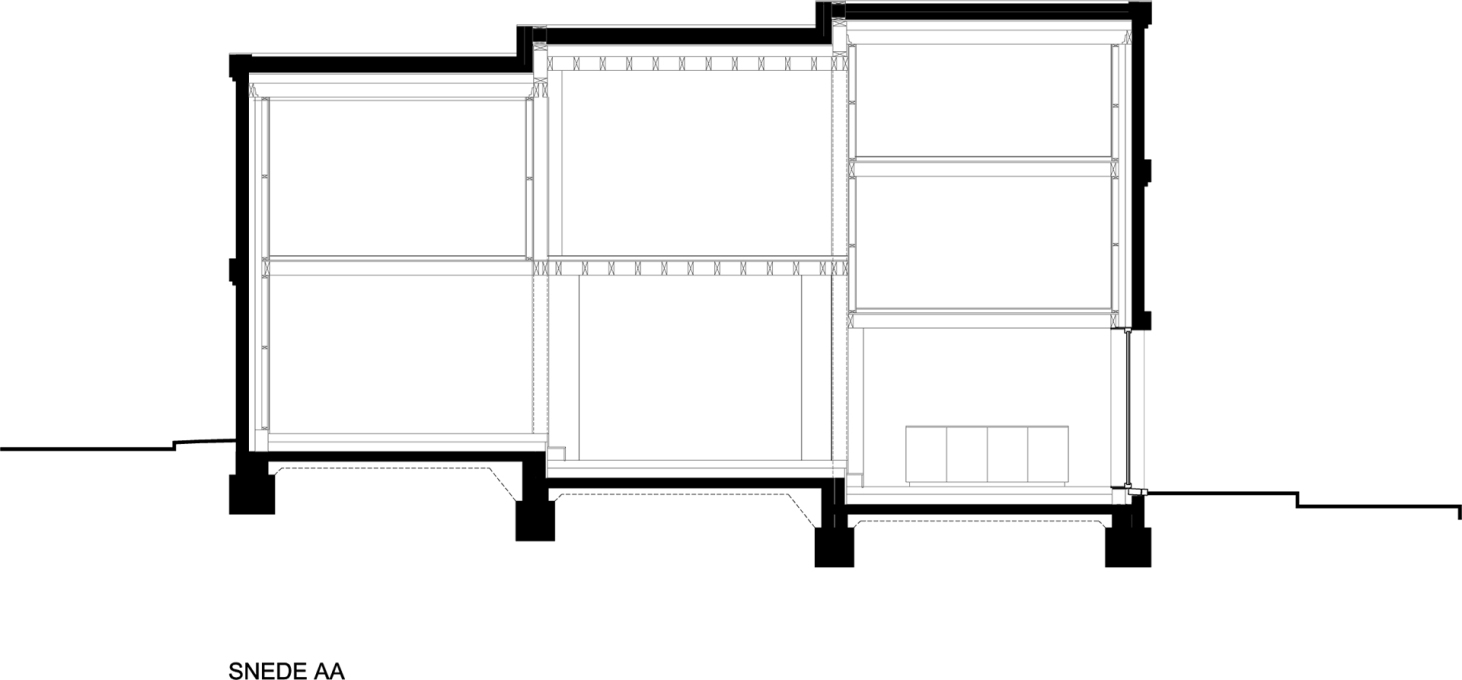

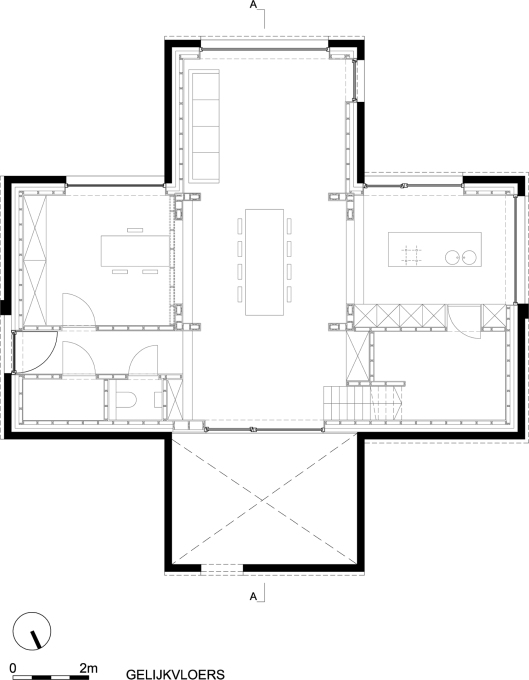

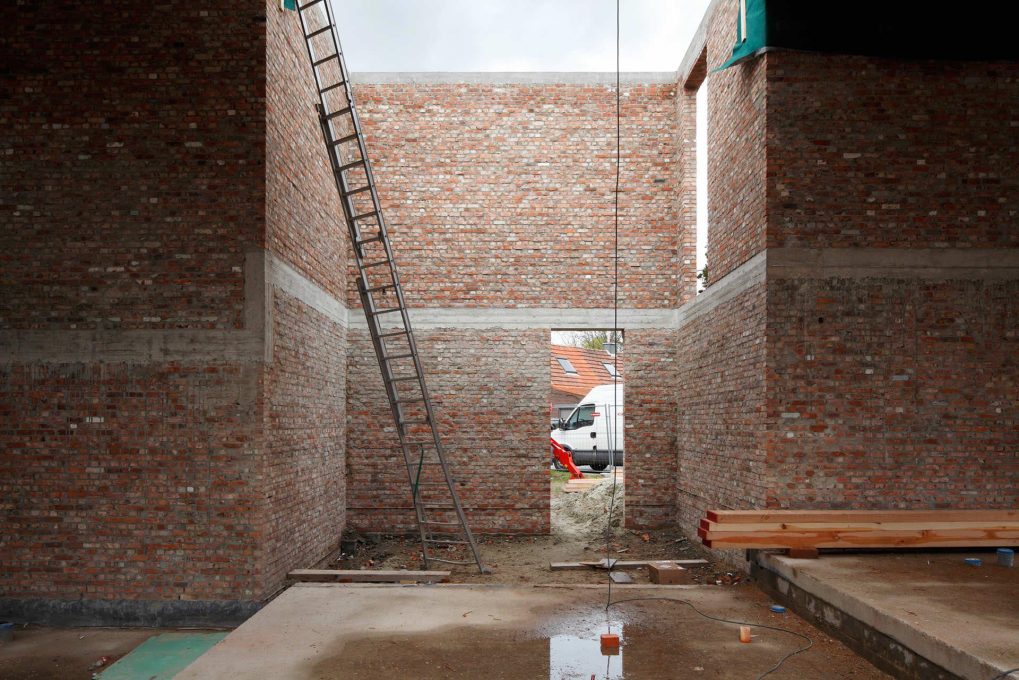

One of these hunches forms the basis for the dnA house: a robust outer shell accommodating and buffering an adaptable interior. Brick walls set out its roughly two-storey-high volume with a flat roof and cruciform layout. This 19-centimetre-thick self-supporting shell provides a durable mould for the house. Its inertia reduces temperature fluctuations, providing warmth in winter and cooling in summer to an interior formed of a light timber framework: adaptable, well-insulated and airtight. So, the house consists of two separate structural casings, eliminating thermal bridges whilst boosting flexibility.

The distinction between the outer and the inner structure of the house is not only evident in its material, but also in its architectural expression. There is a seductive mix of honesty and aesthetics here. The recycled brick walls are lined with concrete beams and thickened where structurally needed, and the inner surface of this casing is smoothed out to receive its slick interior, like a warm and weathered glove. As a box within this box, the compact set of rooms with varying floor levels form a well-arranged and open abode. The ground floor cascades down in a series of three stepped sections, following the natural slope of the terrain and creating enough height at the lowest side of the house for an extra floor, whilst its highest side can be closed off and used as a separate office space directly accessible from the entrance hall.

The wing of the cruciform volume closest to the street serves as a two-storey high patio, bringing daylight into the heart of the house at both levels and visually including the raw brick walls as an integral background element of the interior. On the first floor the patio illuminates a central room that serves as an overflow space for the bedrooms. This room is framed by four functional columns incorporating all the wiring and conduits, forming the technical backbone of the house. At ground level these columns merge with the timber that lines the enfilade of cascading rooms.

The patio also plays an key role in establishing a relationship between the house and the street, its outer wall perforated by a doorway and a window, creating an informal entrance to the house, and an unobstructed glimpse of its innards to passers-by. The house is also set askew to the street, meaning both the informal and main entrances are equally accessible. With Cartesian precision it divides the plot into different quadrants, allowing its four façades varying degrees of formality and informality, publicness and privacy. Thus BLAF not only turn traditional construction methods and sustainability idioms inside-out, but also the established relationships and customs of the typical suburban neighbourhood.

The architects like to describe the dnA House as an “intelligent ruin”, referencing the concept former Flemish Government Architect bOb Van Reeth introduced to promote sustainability through flexibility and adaptable architecture. Though the dnA house is a bit too literal — an almost romantic interpretation of the idea — it has the undisputable merit of exploring new paths for sustainable construction, even if its flexibility in the long-term seems beside the point. For ultimately, how sustainable can a building be when any adaption implies thoroughly rebuilding its inner structure? Likewise, one might wonder: why build an intelligent ruin of this small size in such a stupidly space-consuming environment as suburbia?

Nevertheless, the brick shell of dnA House looks built for eternity and its utilitarian aesthetics will challenge common expectations for a few years yet, whilst on the inside its sparse, precise finish underlines the timber structure’s temporary nature. In the contrast between a house that appears built to last with its more ephemeral inner structure lies a productive interaction between sustainability and style. This is both the greatest asset of the dnA house and also its weakness: on the surface, its design is more about making a statement than about real efficiency per se, but as a statement it is bold and beautifully convincing.

– Stefan Devoldere is an architect and urban planner based in Brussels. He talks, curates and writes about architecture and urbanism on a regular basis, and is currently the deputy of the Government Architect of Flanders.