Writer and architect Sabine von Fischer questions why so much recent architecture prioritises the visual at the expense of the acoustic experience.

Much recent architecture suggests that the acoustic dimension of space is almost irrelevant. It relies on bombarding us with images. And whilst this prevailing visual dimension – and stimulation – is carefully considered by architects, their lack of focus on the aural dimension of space results in many busy communal spaces like restaurants being so acoustically challenging that often you are unable to listen to the people you’re there with.

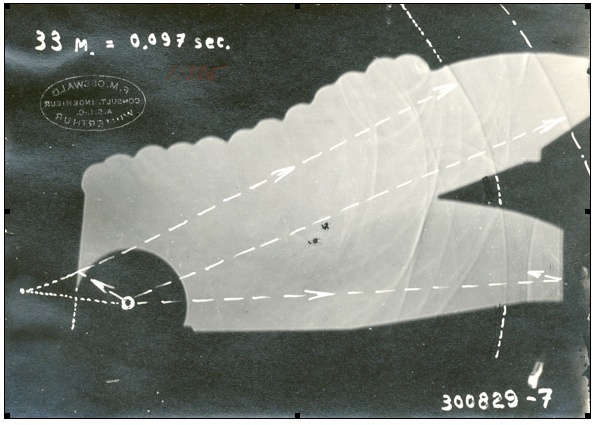

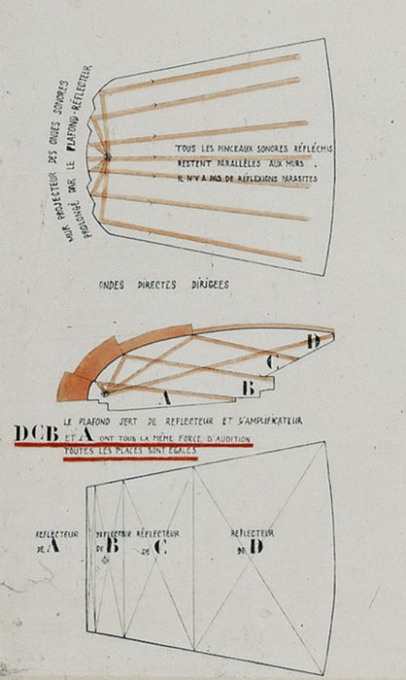

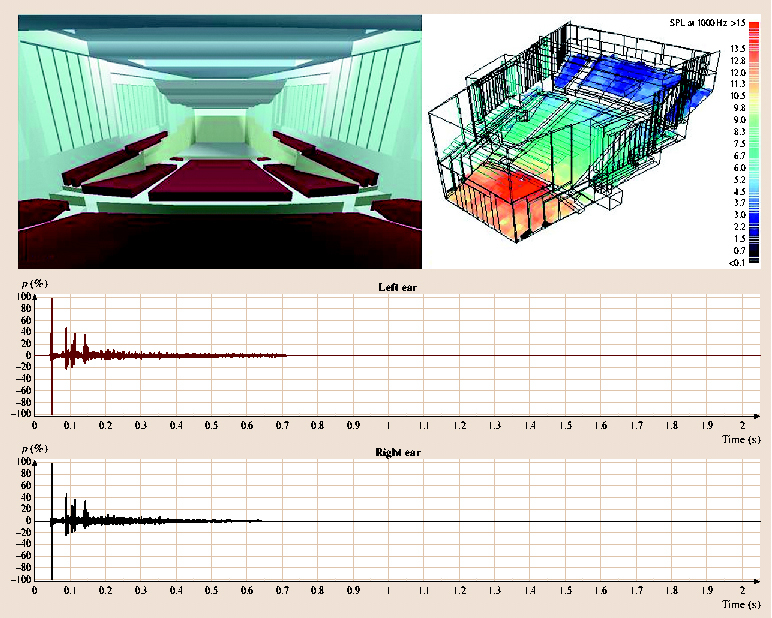

The simplest explanation of why acoustic design is left to chance, or rests at the margins of most architects’ consciousnesses, is the problem of its representation. It seems that we are at a loss for words to describe the sonic qualities of space, as well as the graphic techniques to simulate and represent sound. The existing techniques rarely make it beyond the technical reports or the academic papers of acoustic experts. Despite powerful and persuasive visual representations of sound in the past (see rendering below), there is still a pervasive disregard for sound’s role in forming and experiencing most architecture.

Diller + Scofidio’s work especially lends itself to this critique, as their emphasis on constructed visual narrative often overrides the practicalities of the actual experience of the spaces they design. When in 2000 the Brasserie restaurant in the Seagram Building off Park Avenue in New York re-opened with a new design by Diller + Scofidio (after the original by Philip Johnson had been ravaged by fire in 1995), it was quasi-compulsory for architects to meet there for a drink. Once there, however, one would find oneself sitting in silence, staring at objects, images and video screens, as there was no point in speaking in the midst of a vortex of competing, unidentifiable fragments of noise. Whilst in a nightclub at one in the morning, having an intelligible conversation might not be the point, but when in a bistro at seven in the evening, don’t you want to exchange and understand a few words?

If having met at the Brasserie, one wanted a proper conversation, one had to move on to the bar of the Four Seasons restaurant on the south side of the Seagram building (or if merely a casual chat that didn’t warrant this monetarily, head back out to the street!). When in 1959, Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson designed the interior of the Four Seasons, which became Park Avenue’s most exclusive restaurant, they’d have had no idea it would eventually need to serve as a retreat for those expecting more from a social occasion than just watching plasma screens and video monitors. For in the intimate setting of the Four Seasons, the glass and glazed material is complemented and softened by leather, carpets and plants, whilst in the Brasserie, the glass partitions and hard surfaces produce seemingly infinite resonances – a combined soundscape memorable even after 13 years.

But this acoustic landscape inside Diller + Scofidio’s Brasserie is just one of so many similar examples in communal spaces designed by architects since the turn of the millennium. The theme of its design was “glass and vision” – exemplified by the 50-foot long sheet of lenticular glass that leans against one wall, both display case and support for the seats of two dozen of the diners. The architects derived this concept from the irony that, whilst this restaurant is set in modernism’s quintessential glass tower, it is lodged in its stone base without any views out. The narrative plays with the image of glass, but not with its sonic effects. Entering the restaurant, one’s image appears on the plasma screen over the entrance to the stage-like interior. However, what is a theatre where you can’t hear? Theatre design might be the oldest type of building where acoustics were given great attention, and yet, as the history of theatre design reveals, even then the visual spectacle was often valued higher.

While many theatres and restaurants rely on visual spectacle, there are of course some building types for mass gathering where the intelligibility of speech is a key requirement of the brief, such as auditoria and assembly halls. When these necessarily became larger at the beginning of the modern period, it was a real challenge to ensure that everyone in an audience could understand the speaker. A seminal turning point in architects’ awareness of the importance of the spatial acoustics needed for the spoken word was the League of Nations competition in 1927, in which 377 designs were submitted as competition entries for the headquarters of a new international organisation in Geneva. A major element of the brief was a large assembly hall, in which 2,700 people needed to be able to assemble – and hear the speeches being made. Diplomacy and the peaceful cooperation between all the member nations depended literally on the understanding of what was being said.

In late 1927 Sigfried Giedion commented on the competition, criticising the unconsidered acoustic aspect of the many monumental schemes entered, in contrast to his support for the validity of the modern functionalist approach of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s proposal, which had a proposed assembly hall of 20,000 cubic metres, small compared to other schemes. However, even for this size of auditorium, it would have been very hard for a speaker’s voice to be projected to the back seats. And whilst some schemes, such as that of Hannes Meyer and Hans Wittwer proposed employing loudspeakers, Giedion argued that the technology was still insufficient for broadcasting speech intelligibly.

Nearly 90 years on, the importance of acoustics is still severely underestimated. It is vital that there be far more readily available means for designers to effectively discuss and represent sound in architecture. At the high end of acoustic design, software technologies compute acoustics for concert and performance halls with great accuracy. For the everyday, however, for restaurants, schools, dwellings, hospitals and other building types, architects still lack the tools to embrace acoustic design.

While the image of us all wearing headphones and speaking into microphones and mouthpieces already haunts and captures multiple aspects of life in the twenty-first century, architecture’s function in society reaches into the realm of collective space. In a building’s design, consideration of sound should always plays a seminal role. Are we ready for a shift towards acoustics in architecture? Why can’t the present Image Boom be parallelled not by Sonic Bust, but by a Sonic Boost in awareness?

– Sabine von Fischer is a writer and architect engaged in investigating the role of acoustical and other sciences in architecture. Her Ph.D. from the Institute of History and Theory of Architecture at ETH Zurich is titled: “Proof of Sound. Acoustics as a Function of Architecture, 1920–1970”. She is a session co-chair of the Society of Architectural Historians 68th annual conference: "Sound Modernity: Architecture, Technology, and Media,” being held in Chicago from April 15 to 19, 2015. Call for abstracts of papers still open: closes June 6, 2014.