In the midst of the flurry at Amsterdam’s What Design Can Do conference – reviewed in uncube last week – Elvia Wilk found a moment to speak with Paola Antonelli, senior curator of the Department of Architecture and Design at MoMA. Antonelli had just given a talk centered on her Design and Violence project: a blogging platform on which selected writers respond to specific design objects socially entangled in issues of violence and control. The blog has served as a springboard for a series of debates at MoMA, and has stimulated national and internationl discourse on the political potential of design.

--

EW: I was checking out the “Design and Violence” website this week and was pleased to see the most recent piece about whether architects should be designing buildings used for punishment, like prisons. I wonder, if architects aren’t designing these prisons, then who is? Is it better not to participate at all rather than try and intervene?

PA: I think that right now most architects are not participating. I would like to know the percentage of buildings in the world that were designed by architects.

There are different figures, but recently I read it’s about two percent.

There you go. The building is the fetish of the last generation of architects.

On the other hand, it seems like designers are managing to redefine their profession. When they talk about reconsidering their role today, designers aren’t just continually saying “we’re obsolete” like architects are.

Designers are not at all ideological or dogmatic in most cases. They understand that they’re part of a larger ecology.

And even if they don’t intend for a project to influence this ecology, they sometimes find out three steps down the line that a design has had this domino effect.

Exactly. I’ve seen it happen. I did a show in 2008 called Design and the Elastic Mind, and in the lead-up to the exhibition I held a series of salons with Adam Bly, who ran the science magazine Seed. We organized around a dozen of these salons where we put my best designers together with his best scientists in panels of four speakers. One night we had the mathematician [Benoit] Mandelbrot, and right after him we had the architects Aranda\Lasch. We also had Paul Steinhardt, the physicist holding the Einstein chair at Princeton. We had all these amazing people, and at the beginning the designers and the scientists were so timid, but then some collaborations actually got started. It’s really interesting to see how designers, by being completely open, and by not wanting revolutions to happen immediately, are very effective in impacting other fields.

I’ve prodded designers before about corporate collaborations, about what it means to be complicit versus critical and – again – whether it might be better in some cases not to participate at all. Could it be considered a peculiar kind of elitism not to work with other fields and institutions?

Designers get asked quite often if they feel like they’re tools of the industry. But you don’t know how many artists I know who think they can descend towards design in just a few steps! And they fail miserably! Of course there are exceptions –Martin Puryear is the one who surprised me the most; he was having a retrospective at MoMA, and the people from the store came to me and said, Martin wants to do a design piece. I thought, oh my God, it’s going to be a disaster. And then he designed a great pan scraper to clean your pots and pans! They still sell it today.

I think the same about Olafur Eliasson’s Little Sun project. I don’t know if a designer would have used a sunflower shape for the light, because there is something very literal about it – it’s something a designer shouldn’t do. That’s why I like it. I might have a hard time walking around with a sunflower hanging from my neck, but it doesn’t matter what I think, because it’s not for me. There are examples like these of artists doing good work in design…but also many examples of the contrary.

So art can’t subsume design. What about architecture? Can architecture subsume design, or vice versa?

I studied architecture in a polytechnic university, so I come from that tradition. And as far as I’m concerned, architecture is a branch of design. It’s very simple. Across history, the relationship between the two has been that sometimes architecture took design by the hand, and sometimes design took architecture by the hand. Right now, design is taking architecture by the hand, as it did in the 1960s. This happens very often when there are booms in technology – it also happened right after World War Two. When there’s a big influx of new technology, architects start experimenting and making objects, and then they think of making something bigger with it. For instance, today there is so much discussion about “growing” architecture with algorithms – but the algorithm is a design and engineering concept much more than an architecture one.

The algorithm?

Yes, if you look at architecture and design, which discipline is more comfortable with – or has already been using – the algorithm? Designers have adopted the idea of starting with a unit that then grows. I’m not saying that architecture today is just blown-up things, but when I studied it, it was all about the context, the territory, and learning from the typology – though maybe that’s because I’m Milanese. I see architects today just designing objects and then putting them in places.

Plop-down architecture, so to speak. So do you think that architects shouldn’t act like designers, making objects rather than infrastructures?

I don’t want to say yes or no a priori. There are no general rules. But I can say that the most beautiful aspect of contemporary culture for me is that people are becoming comfortable with ambivalence. Ambivalence is a state of mind but it is also related to quantum theory. I love it when scientific theories become life without people even knowing it.

There must be a lot of examples of that happening.

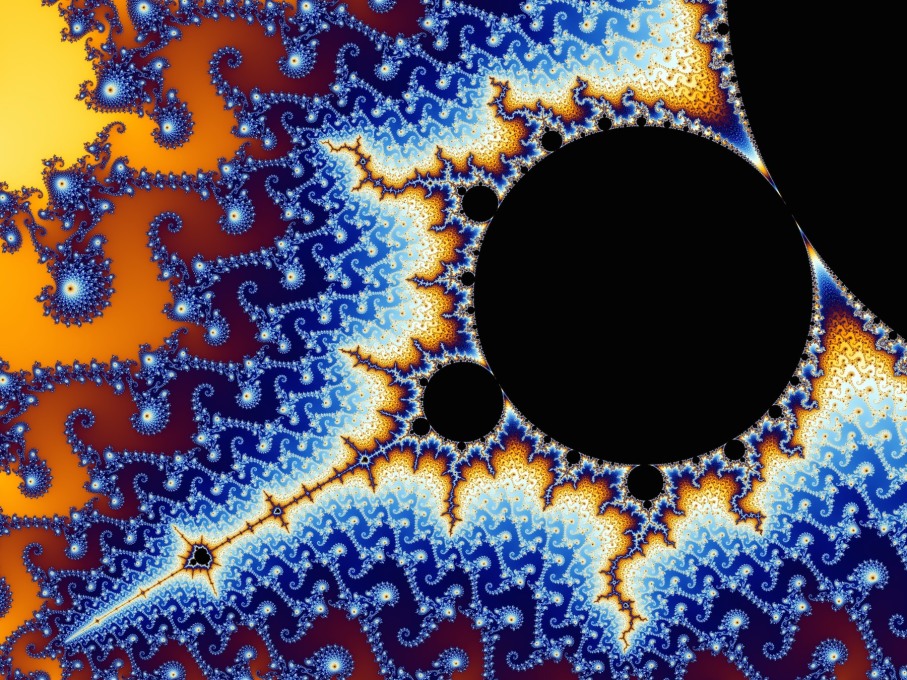

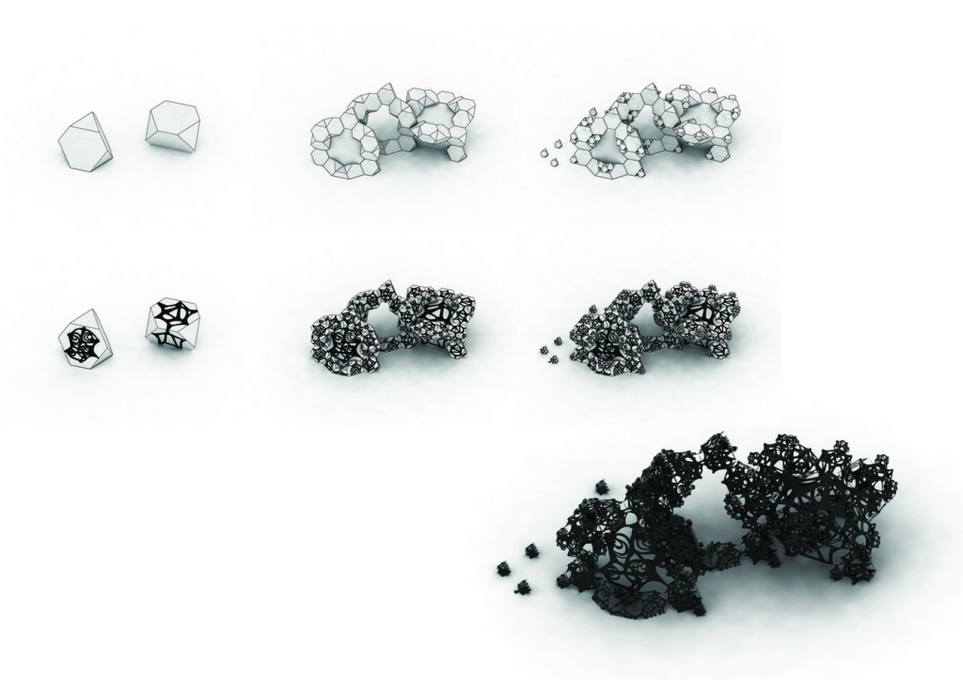

My thesis was called Fractal Architecture and it was a critique of the [1988] Deconstructivist Architecture show at MoMA. When Philip Johnson interviewed me for my job I told him about it and he loved it – he had such a taste for polemics. In my thesis I said that Johnson and Wigley had presented Deconstructivism as a style, when these architects did not actually have elective affinities of style. They were part of a culture, a certain zeitgeist that had to do with fractal geometry – even though they might not even have known about it. In particular I delved into Coop Himmelb(l)au and their work, spending a lot of time in Vienna with them. They didn’t even know who Mandelbrot was – it didn’t matter. At that point in history it had become impossible to photograph architecture; there was no way to represent architecture with sections and plans and axonometries. I saw that as connected to this idea of the fractal, to this new geometry and way of reading the world.

Similarly, I think the idea of quantum theory is slowly but surely influencing us. Particularly I think the transition in our understanding of gender is so beautiful; a central ambivalence is emerging. Ambivalence, to me, is the key. It’s not a negative, it’s just the capability to accept many middle states, to accept change, and to accept the idea that things can change. Even the idea that designers had a steady job once upon a time, and today they know that they might have to start their own companies, or two companies even. It’s ambivalence. It’s beautiful.

- Elvia Wilk

www.designandviolence.moma.org