The original design of the Free University in West Berlin is a cautionary tale of a radical 1960s dream gone sour: a lightweight modular megastructure, with input by Jean Prouvé, intended to offer endlessly extendable and flexible space, which proved disastrously unresolved in the making. But as Florian Heilmeyer reports, in its subsequent phases of development, including a renovation by Norman Foster and the latest iteration by Florian Nagler Architects, many of the initial problems have been resolved, offering a story of gradual redemption for a building that only now might finally be fulfilling its inspired original intentions.

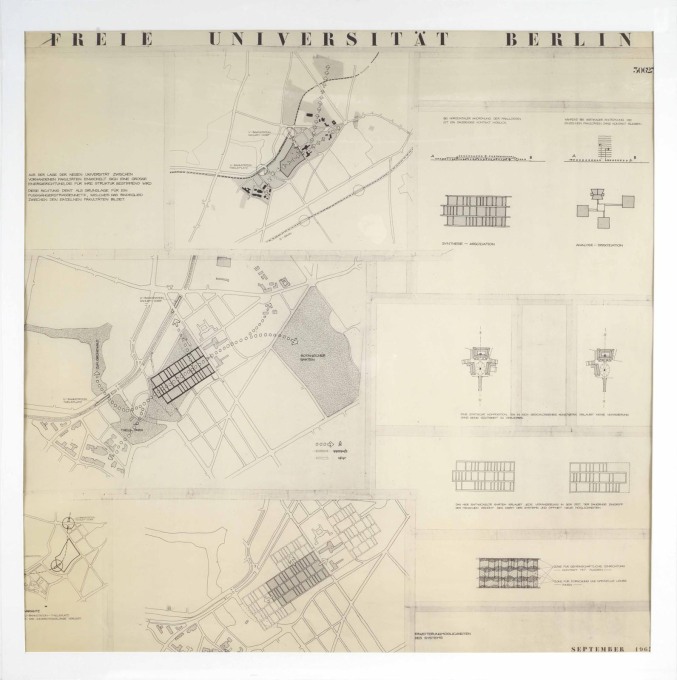

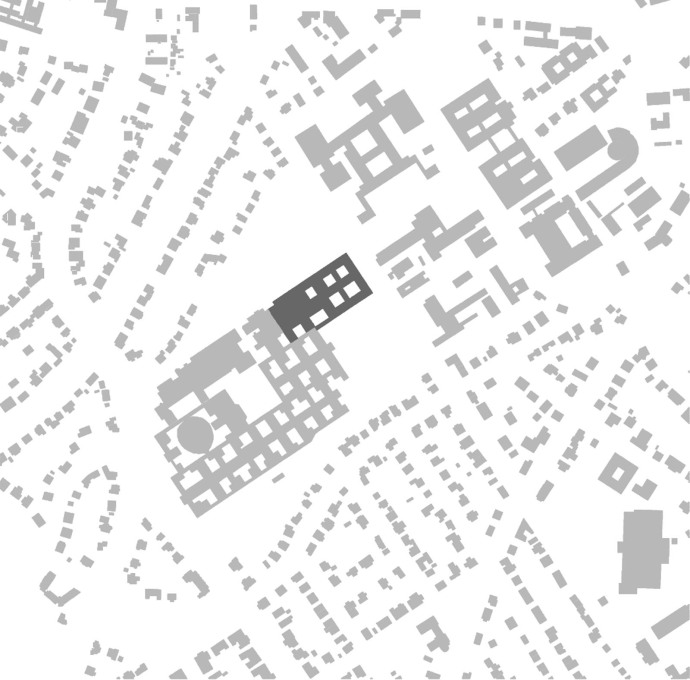

If you want to visit what might well be West Berlin’s most radical building, you have to drive a pretty radical distance from the city centre. The main building of the Free University – built in successive phases since 1967 with the latest completed this year – is located in the wealthy suburban neighbourhood of Zehlendorf next to a U-bahn station with the fitting name of “Dahlem-Dorf” meaning “Dahlem Village”. The original design was by Team-X co-founders Georgis Candilis and Shadrach Woods in collaboration with their office partner Alexis Josic and German project architect Manfred Schiedhelm. Construction of the building started on site in 1967, although even with its subsequent additions the building still hasn’t reached the enormous projected size of 350,000 square metres which the original 1962 international competition asked for.

West Berlin‘s new university was founded in 1948 in reaction to the division of the city, given the existing Humboldt University was now based in the Eastern – Russian – sector. The title of “Free University” itself hints at the American idea of re-educating Nazi-Germany into a democratic and open society much in their own image. Plans for a new main building had been tossed around and various locations discussed, when the building of the Berlin Wall sped things up a bit. The Zehlendorf site was chosen mainly for reasons of its availability: it was a huge area previously used mostly for fruit cultivation and completely owned by the city.

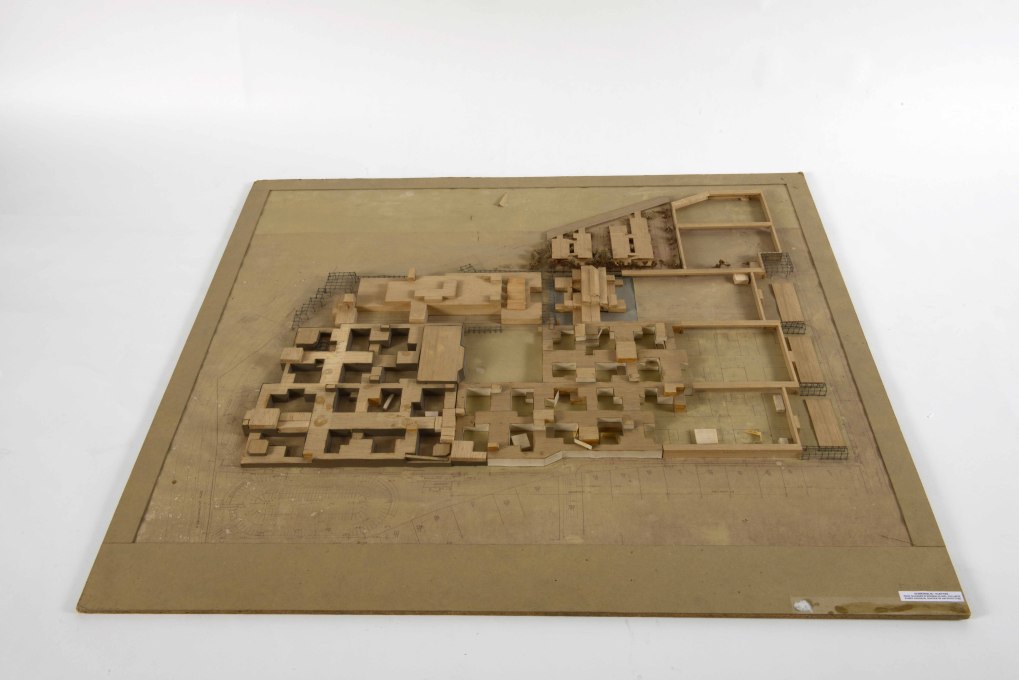

With the competition brief asking specifically for new forms and ideas for how a new university could look or function, the architects developed a truly revolutionary scheme. While most of the other contributions proposed clusters of high-rises, Candilis-Josic-Woods sketched up a wide-spread, carpet-like structure of two- and three-storey high, modular spaces. The organisational structure with its covered streets and corridors, passing around inner courtyards, offices and auditoriums took its inspiration from historic Arabian cities and souks rather than its suburban surroundings of the then walled-in West Berlin. The architects’ motto was “instrument, not monument”, creating the idea of an ever-changing machine for learning, aimed at maximising spatial flexibility for the buildings’ users: all rooms and spaces within the basic spatial system were designed to be easily rearranged. Like a bookshelf, the entire building should be changeable with a simple screwdriver. If this could have been realised fully, all façade modules should have been demountable and able to be placed anywhere else in the building, turning it into an ever-changing machine for all future (spatial) needs the university might ever have.

The radical ideas for the buildings organisation and construction techniques quickly proved far too ambitious. Even with different colours on the sunblinds outside and on the carpets in the “street” corridors inside, denoting each department or institute to help students and teacher, the inner structure of the vast building was mazelike and despite all its rectangular and systematic order, surprisingly confusing.

At the same time the construction of the façade modules also proved difficult. They were developed by Jean Prouvé, who based them on Le Corbusier‘s Modulor and fabricated them from Corten steel trying to make them extremely light-weight so that they could easily be demounted with their screwdrivers and carried by two people. The steel was meant to weather slightly over time, creating a nice patina. Yet it rusted far too quickly, and the extremely thin modules let air and water stream inside causing increasingly severe construction damage even before the inauguration of the first phase in 1973 – its most popular aspect among its out-upon users being its quickly earned nickname of Die Rostlaube – “the Rust Bucket”. “With its water spots and the roof panels hanging loose, the interior had a ruin-like appearance”, notes the Architecture Guide Berlin charmingly.

Yet even though the Candilis-Josic-Woods partnership broke up in 1968, the university still reprised their scheme when the second phase was built between 1973–79. With Manfred Schiedhelm now in charge, the add-on exactly followed with the organisational structure but significantly changed its method of construction. Corten was replaced by aluminium turning the outer appearance even more futuristic and machine-like while – crucially – preventing any more rust.

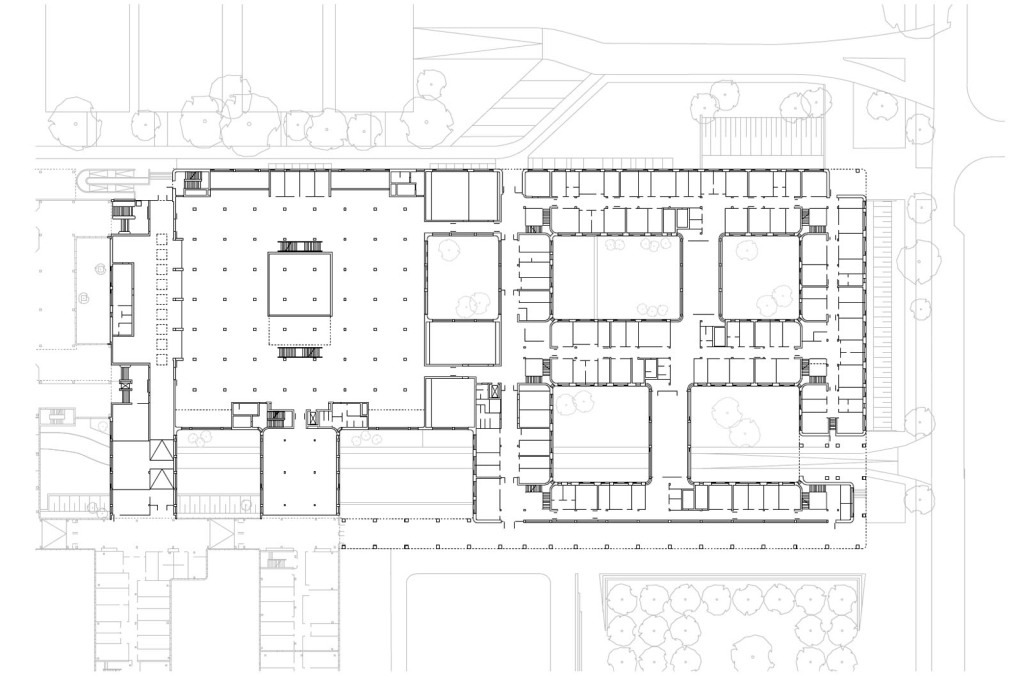

Called, perhaps inevitably, the Silberlaube or “Silver Bucket”, this increased the inner confusion of the Free University. An ever more excessive way-finding system with hundreds of signs pointing in all directions actually made orientation even worse. A popular joke doing the rounds in the 1970s was that the university might actually have as many as 25,000 students, if only they could be found. When the refectory and library were added in the mid-1980s, they were constructed as single big buildings which docked simply onto the existing building rather than following its modular grid.

The different parts of the building progressed into various stages of decay, until in 1997 Norman Fosters’ office was commissioned with comprehensively renovating it, completing this in 2005. Cleverly analysing the intentions of Josic-Candilis-Woods, Foster replaced the entire cladding of the rust bucket with new modules which retraced the original façade’s partitioning, yet made of bronze which patinates in a similar way – without the rust. The rounded corners, the colourful sunscreen elements, the white doors and the prominently accentuated window profiles – Foster managed to integrate all the distinctive elements of the original design in a clearly modernised, technologically updated version.

It is remarkable to see a radically modern yet undoubtedly difficult building like this being treated so carefully by its user over so many years. It’s clearly over-ambitious, avant-garde ideas were no reasons for the university to tear it down and replace it with something easier, cheaper or more efficient. Instead, the Free University today is a prime example of what can be achieved if mistakes are analysed without prejudice, and alternative solutions examined which still stick to the ideas and intentions of the original design – although clearly at a cost.

This loyalty to the original architecture was proven again with the recently completed fourth extension to the building. Florian Nagler Architects won the international competition in 2004 with a proposal that basically continued all the ideas of Josic-Candilis-Woods, while again improving the construction techniques.

Their design in fact continues the existing structure so exactly that it is hard to distinguish between the old and new parts from just looking at the floor plans. Nagler’s new building again shows a carpet-like structure winding around some inner courtyards. Like Foster before him, Nagler continued the proportions and partitioning of the original façade, but converting it into a loadbearing structure clad in cedarwood, preweathered to a tasteful grey. Where Foster had already given up on any idea of easily replaceable modules, whilst still imitating their look, Nagler has given up trying to imitate the modular look too closely at all, making much larger window openings possible. This is perhaps the most important factor for the Free University, as these windows not only turn the previously dark, sometimes almost claustrophobic interiors into a transparent and light-filled structure, but also allow many vistas and visual connections between the different parts of the building, solving in one fell swoop almost all the problems of difficult orientation.

So Nagler’s “Wood Bucket”, which was inaugurated in 2015, adding another 12,000 square metres to the earlier labyrinth, has succeeded in giving the dark structuralism of the building an open and relaxed atmosphere. Strolling through the light-filled new corridors and offices, and for the first time in the building’s history, it seems feasible that this building could be further and further extended – bucket by bucket – and that this might even be a good idea. Come on, roll out this carpet!

This is the third installment of uncube’s series of exclusive essays, interviews and case studies to accompany Radically Modern. Urban Planning and Architecture in 1960s Berlin an exhibition at the Berlinische Galerie, that looks at the radically modern buildings and urbanism of both East and West Berlin.

Radically Modern. Urban planning and architecture in 1960s Berlin

until October 26, 2015

Berlinische Galerie

Alte Jakobstraße 124–128

10969 Berlin

Germany

uncube are media partners of Radically Modern. Please check the related articles, including interviews with the exhibition’s curator Ursula Müller and with the radical Austrian architect Georg Kohlmaier.

Coming soon: an exclusive interview with Daniel Libeskind about his relationship with Berlin, and the tale of the TV Tower on Alexanderplatz, once a futuristic space-race icon of the GDR and today the undisputed icon of the unified capitalistic city.