Over eleven years during the first half of the twentieth century, two heavyweights of architecture and industry collaborated to construct a modern office complex that still exerts an architectural legacy today way beyond just the design of the office environment. Frank Lloyd Wright met H.F. Johnson Jr. – head of the cleaning products company SC Johnson – in 1936 and together they set about creating the Johnson Wax Headquarters in Racine, Wisconsin. Herbert Wright (no relation) took a trip 95 kilometres north of Chicago – on one of the free tours organised by the company during the Chicago Architecture Biennial – to Racine for uncube, and waxes lyrical (naturally) about an industrial complex built with the workers very much in mind.

When HF Johnson Jr., head of the cleaning products company SC Johnson met Frank Lloyd Wright in 1936, Johnson recalled that “he insulted me, and I insulted him. But he did a better job”. But from this start came one of the twentieth century's most spectacular and innovative offices, the Administration Building at the Johnson Wax headquarters in Racine, Wisconsin. Opened in 1939, it was followed by the adjacent Research Tower (1950), and also a great Wright house, “Wingspread”, built for the Johnson family nearby.

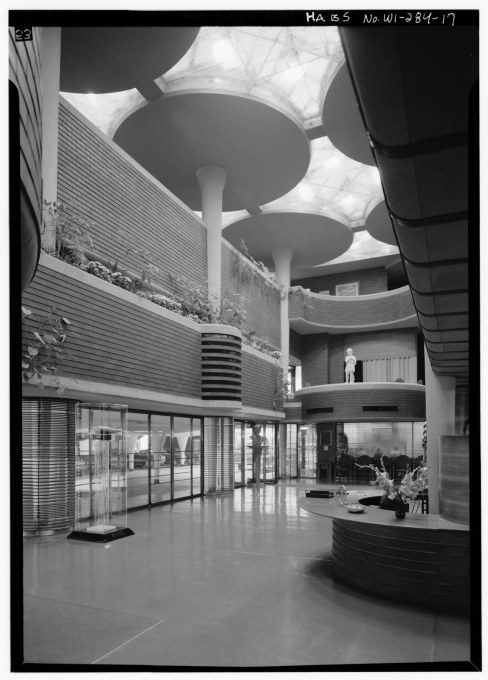

The Administration Building is essentially a two-storey rectangular-plan box of brick, almost blind but for two thin horizontal glazing bands, but on one side, a third storey of offices rises (Wright called this the “penthouse”), with symmetrical angled wings and two circular service core heads. Most of the ground floor inside is a single space called the Great Workroom, a vast open office full of light falling through its most spectacular feature, dendriform concrete columns spaced in a ten by six formation on a six-by six metre grid. Each is 23 cm wide at its base but fans out to 5.5 metres with edges almost touching at the skylight ceiling two stories above. Wright had to prove that a column could support 12 tonnes, and when tested, it took 60 tonnes to crack one. He referred to their tops as “lily pads” and the ensemble as “a glade of trees”. The upstairs floor around the edge looks down onto the Great Workroom, cantilevering inwards from the outermost columns.

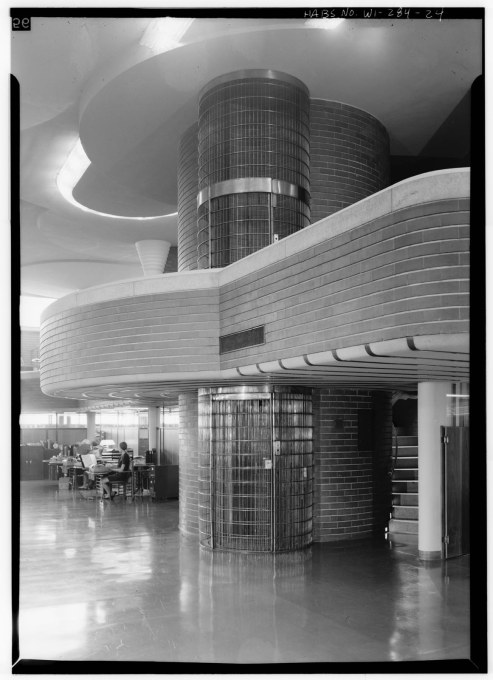

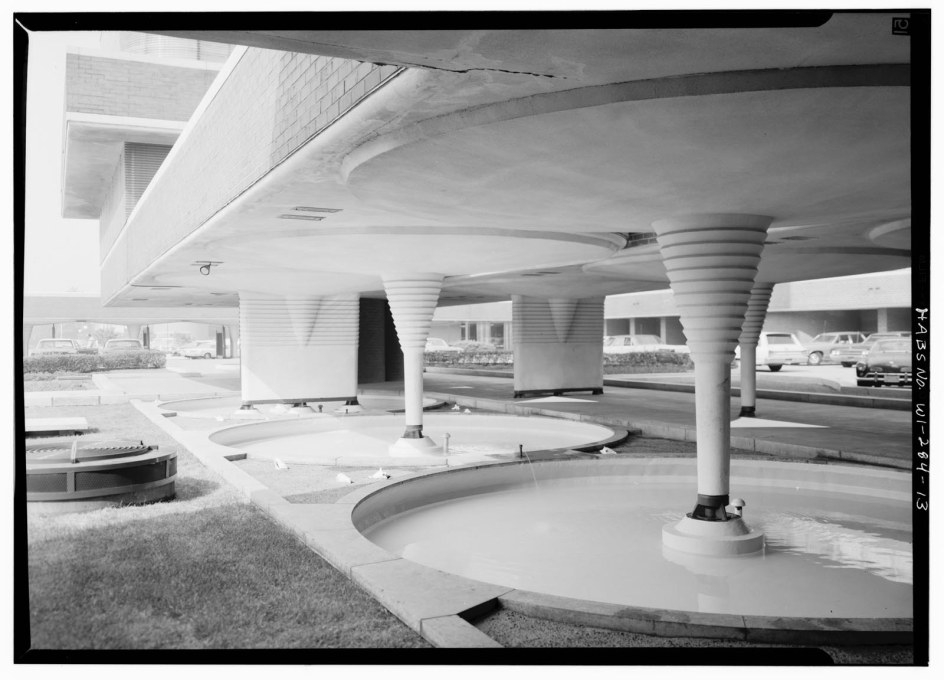

Despite its light, you can't see out from the Great Workspace. Its glazing is clerestory and made of horizontal pyrex glass tubes rather than panes, and appears peripheral like the distant edge of a forest. The Workroom has a precedent in Wright’s since-demolished Larkin Building in Buffalo (1906), with its open office below a skylit atrium. There, Wright had pioneered air conditioning, and designed bespoke furniture. At Racine, the air conditioning pipes (“nostrils”) are behind round “birdcage” lifts, and again he designed the furniture. His original three-legged chairs had to be replaced because people kept falling off them (something he acknowledged only when he did the same). More dendriform columns rises three stories, defining a lobby between the Great Workroom and entrance. Outside, there are even more columns, shorter and supporting the cover extending into the car park, some rising from circles of water like frozen white whirlpools.

From the outside, with its rounded corners and horizontal glazing, the Administration Building is a stunning example of the streamline Art Moderne style. Its strong texture inside and out is shared with the Wingspread house, finished the same year. Rather than a form with fluidity, this is a sharp-cornered building, with four wings extending off-centre from the hub of the main living space, which itself surrounds a solid, central brick feature containing the hearth and rising into an octagonal pyramid with horizontal skylights and an offset art-deco lookout vantage structure. Back at the Johnson corporate campus, Wright was commissioned again in 1943 to design a new research centre. The Research Tower was completed in 1950, and like the Administration Building, it shares the same fluidity and texture. Its form is different but just as radical. 46.6 metre high, it is one of only two Wright towers built. The other was the 67 metre-high Price Tower, completed in 1956 in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, while his 1,600 metre-high tower, The Illinois, remains a vision.

The floors cantilever from a central core, and a narrow staircase is the only access. Square floors are overlooked by recessed round mezzanines, and this two-floor configuration is stacked six times. Wright's disdain for the view of the then-industrial townscape of Racine (he had initially suggested that Johnson build out of town) again resulted in glazing of horizontal pyrex tubes. But unlike the Administration Building, glass dominates the façades rather than brick, which appears as thin bands. The resulting light inside was so bright, scientists were initially issued sunglasses. The 7,000 tubes would stretch 27 kilometres (but still not as much as the 69 kilometres of Administration Building tubes!). With its translucency, the tower's solid parts evoke a pagoda.

Both of Wright's buildings at the Johnson campus came in way over budget, but Johnson wanted the best. At Racine, Wright anticipated the future with more than futuristic styling. The brick texture finds echoes decades later, in modernist buildings that moved beyond cladding or concrete surfaces. Richard Seifert would cantilever the floors of London's 183 metre-high Tower 42 just like Wright's tower. Atria would be revived in the 70s by architects from John Portman onwards. And there's even a hint of high-tech style in the way metal “mullions” support the tubing. Not least, the Great Workroom anticipates the contemporary open office. Nowadays, these are stacked on great floorplates to maximise profit, but Wright designed his floor – and everything from furniture to structure – for the wellbeing of workers.

– Herbert Wright is an architectural journalist and historian, author and art critic based in London.

During the Chicago Architecture Biennial, SC Johnson are offering free Wright Now excursions, including travel from Chicago to Racine and back, with a full tour of Frank Lloyd Wright's work at the Johnson campus.