uncube’s forthcoming issue no. 43: Walk The Line will focus on the role of the hand drawn in architecture in the time of the burgeoning species of the CAD Monkey. As an artist who contemplates ways of seeing whilst feeling the effects of constant digital mediation, Quayola seemed the perfect person to speak to. In his practice he uses cutting edge technologies in “a traditional way”, working with computational algorithms to translate iconographic imagery into complex new forms. uncube’s Fiona Shipwright caught up with him at the opening of his exhibition “Iconographies” at Berlin’s NOME Gallery.

You have developed a really interesting and innovative aesthetic approach, how did the work you’re showing in this exhibition come together?

All these pieces are part of a larger body of work that I’ve been developing over the past ten years. I’ve produced several pieces looking at different subjects but in particular with the idea of “objects of perfection”. The works I’m showing at NOME are the latest iteration in this series. Up until now I’ve mainly been working with video installations – this is the first time I’ve shown exclusively physical objects, which is liberating in a way.

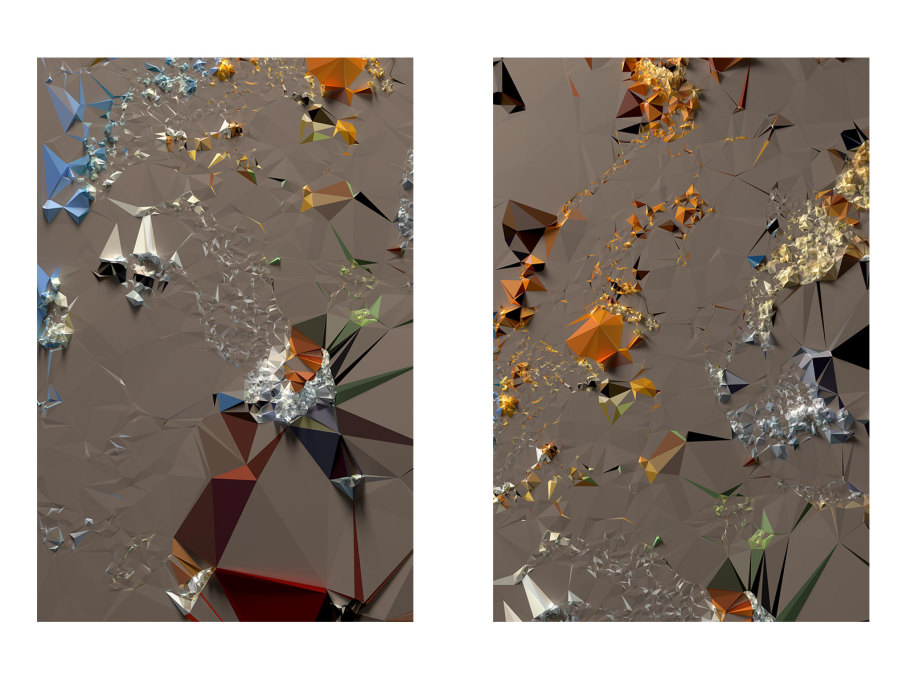

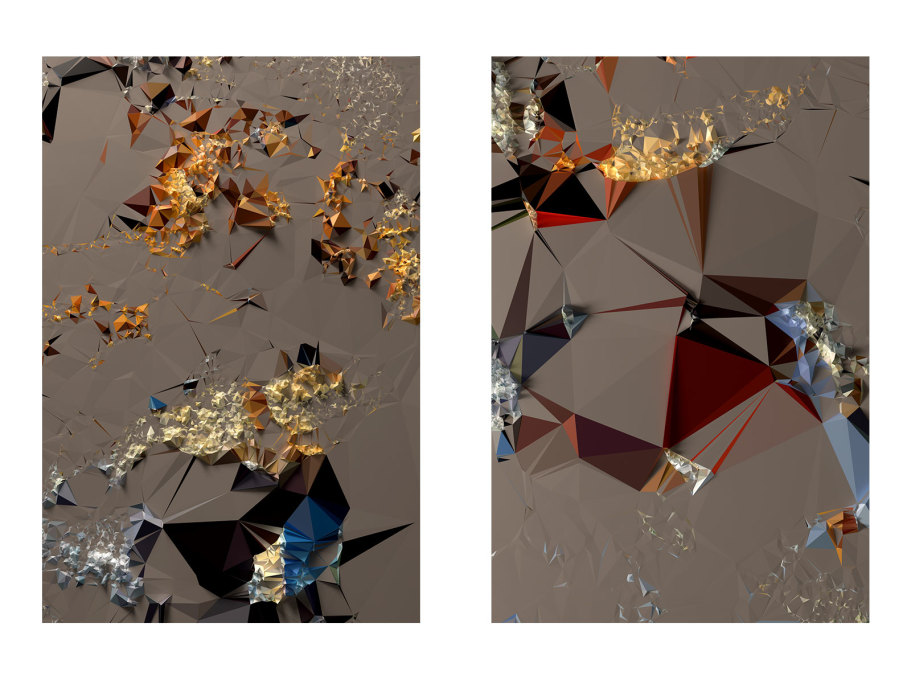

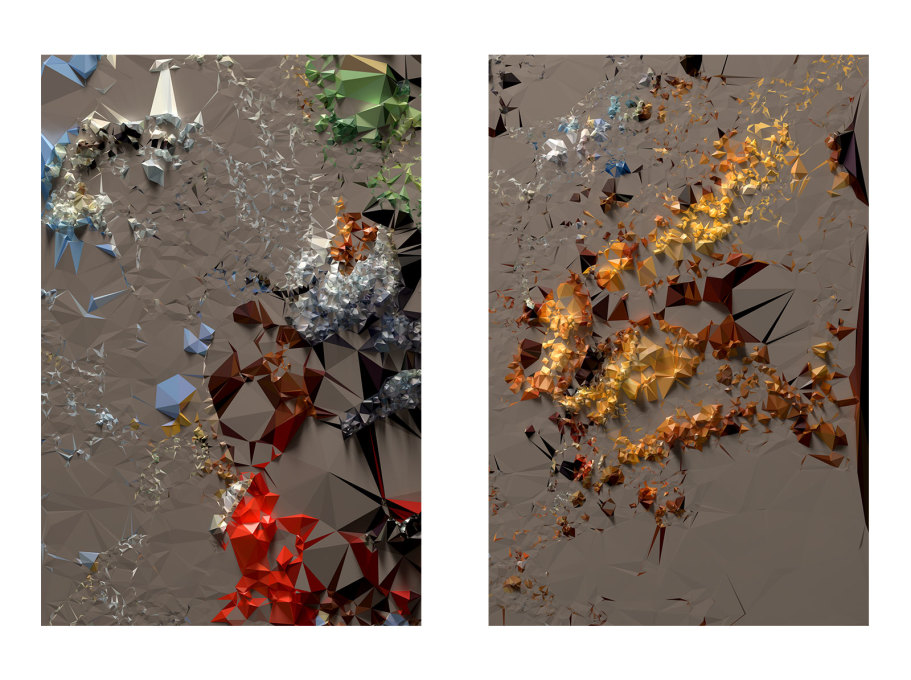

As the title of the show suggests all these pieces engage with iconographic themes and narratives – in this case through paintings – and reconstruct them in different ways. Removing these narratives allows for a focus on the purely visual characteristics, almost like looking at these paintings with a complete detachment, allowing for new interpretations. I think my work is generally about vision, about different ways of “seeing”. Growing up in Rome I was surrounded by and interested in traditional iconography but unable to fully engage because of the weighty historical or cultural baggage associated with it. After I moved to London and began travelling back home I found I had a new perspective on them and that that change was something I wanted to document.

In terms of “taking away” from the original piece, which is more interesting to you – that absence or the introduction of something new? Is it about stripping or interruption?

It’s always been about a celebration of the original piece but over the years the works have become influenced by what’s happening in contemporary culture not as a result of deletion or interruption but seemingly constant mediation of the digital kind. This idea that you are very often viewing an original work through the eyes of a machine. I am interested in how this changes our perception of what’s around us.

How does your choice of medium affect this? I’m interested in the fact that you work with so many – video, static imagery, sound – do these all constitute different ways of seeing for you?

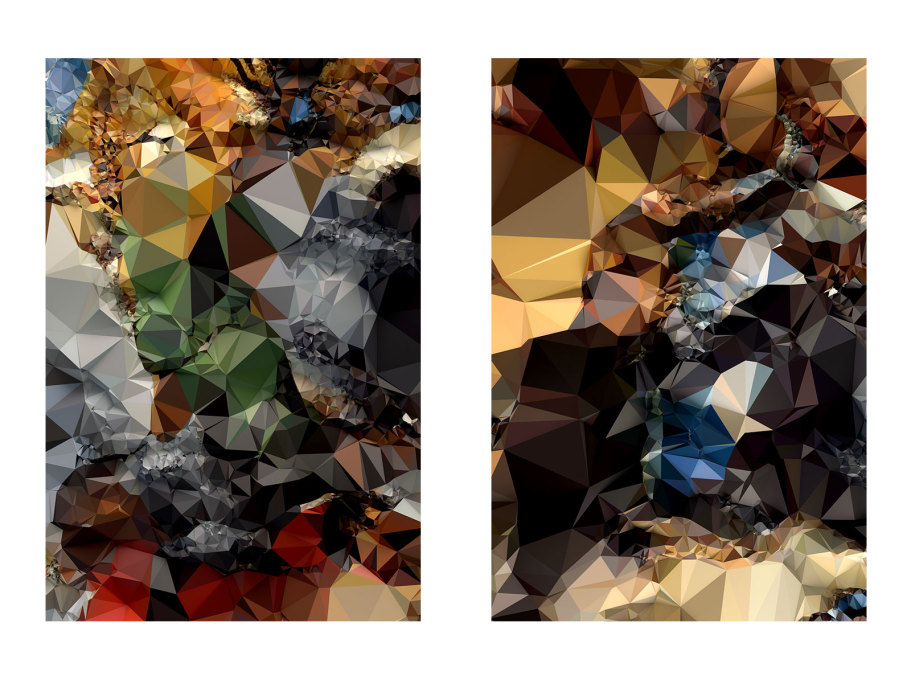

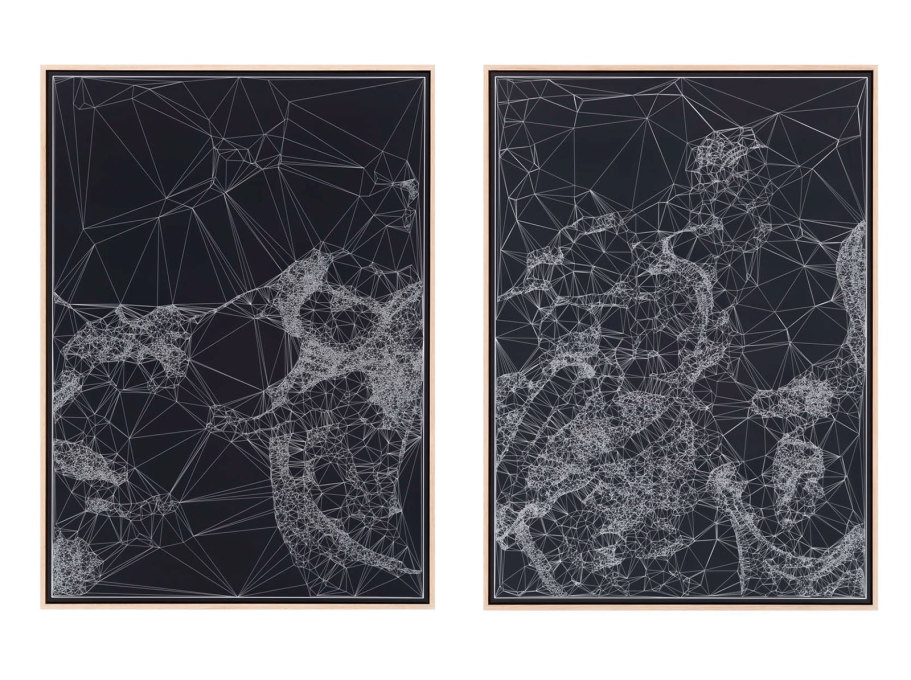

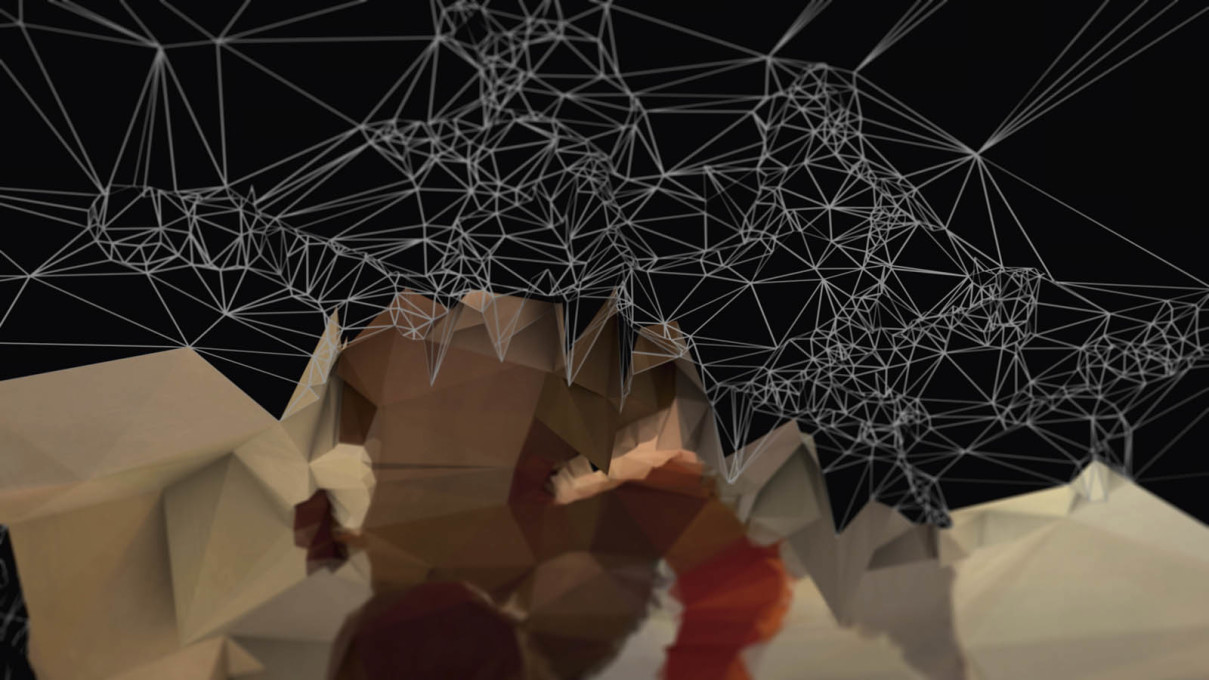

A lot of what I do is actually very painterly, so regardless of the medium, the works are very traditional in a sense. All the works in this show are the result of specific systems, based on algorithms and which arise from a conversation with a machine. So it’s not that I am sitting and drawing little different-coloured dots one by one to create an image but rather I am establishing and developing systems. By changing the rules of these systems I achieve this kind of imagery. It’s rather like operating a musical instrument, or a synthesiser that I calibrate in order to achieve what I consider to be the “richest” image. That’s the traditional aspect: looking at colour, design and composition as though I was drawing in a gestural manner.

Rules and systems – that implies that things can go wrong. Are you interested in error, in glitches?

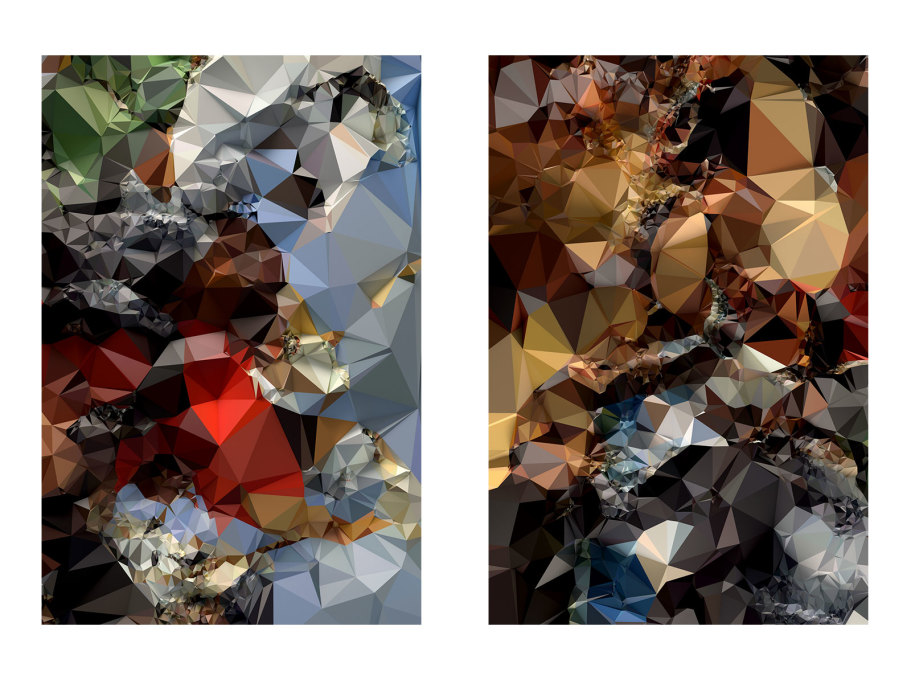

That idea is at the core of what I do because I am somehow misusing these computer algorithms. I don’t think the results can be described as glitches or errors as the processes are quite controlled but essentially I’m calibrating them in unusual ways. Certainly it’s an aesthetic that’s very related to how computers display images – something I have always been fascinated by – so in that way glitches might be a reference to a certain kind of imagery but I think the process is very controlled. That allows me to reach certain outcomes, such as producing images that are completely abstract, that you’re not really able to deduce any narrative from or perceive any form from the original painting. That’s very deliberate. Instead I’m interested in creating new objects of contemplation that have completely different qualities of their own but at the same time are based upon the very same visual characteristics of the originals.

If you get quite close to some of the works you lose a perception of scale – there’s nothing you can detect that give a hint, such as the grain or texture of paper. It’s almost like a sculpture behind glass. You can see there is volume but at the same time you cannot quite understand it. I’m really interested in the ambiguity between 2D and 3D.

For previous works you’ve taken pieces and shown them in the spaces where their “originals” hang. Is that relationship between the work and its space important?

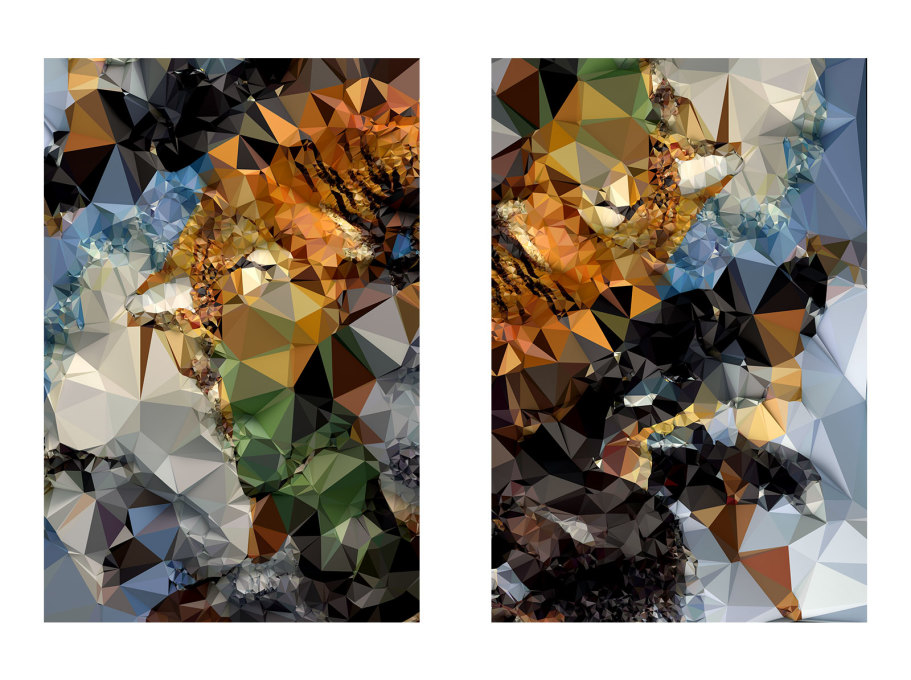

Yes and no. The relationship is crucial in the sense that I’m not only interested in developing finished objects; I’m also interested in the tension and linguistic difference between the original and the end result. In this show, it’s mostly achieved by the title of the piece and by some hints. For example, Iconographies #81-20, Adoration after Botticelli – taking Botticelli’s Adoration of the Magi (1475), I generated three responses, which describe the painting in completely different ways. It’s like using the same alphabet but for different languages. Firstly, there’s a written description from the sixteenth-century art historian Giorgio Vasari. Next to this is the code that has been spat out of a computational process that also “describes” the painting. Then there are the three abstract Ditone prints. I’m becoming increasingly interested in exploring these tensions, but find their expression is becoming more and more subtle.

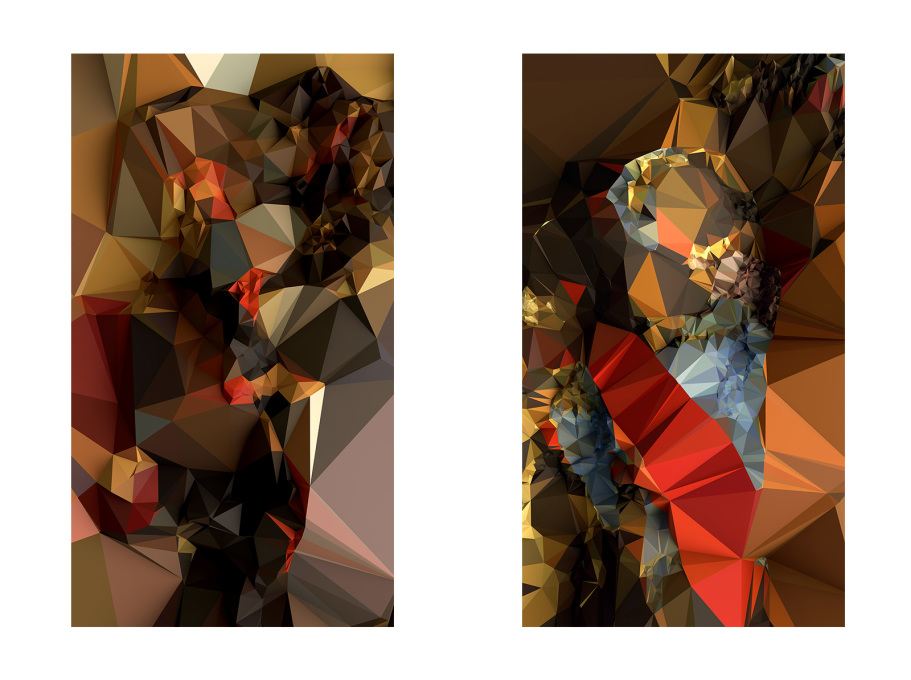

In another work though, Iconographies #16-01, Venus & Adonis after Rubens, there is a clearly identifiable piece of the original. It’s a component of time. It reminds me of ruined frescos, of objects that once “were” and now find themselves in a process of metamorphosis, which prompts a viewer to think of what could be, looking at what’s been left in the frame now that everything else has fallen apart.

You’re currently running a studio with students at the Architecture Association in London. Can you talk a little about how you have chosen to approach that?

By getting the students to experiment with this very same topic, engaging with the artworks as architectural sites or data sets, giving them the same software that I’ve been using. It’s an eight-week course called “Machine Vision” run by myself and Tommaso Franzolini. It’s been an interesting journey. In the beginning the students were always describing and talking about the paintings based on elements that they could recognise; the sky, for example, or the ground, or a particular tree. Slowly I got them to look at the work in a different way by using and playing with the software. By the end of the course they started talking about non-representational aspects or about different ways of visually slicing the images. That was the intention, to get some to distance, to look at things in a different way.

One would imagine distancing would involve taking a bird’s eye view but in your work you’re actually going in very close to achieve the same idea of an overview. Has that notion of scale changed over the course of your work?

It has and continues to vary. Some of these pieces in this show deal with whole paintings and others look at very specific details. For me scale is one of the parameters that I play with in the systems I create; resolution is another one and so on. This was in part inspired by Google Art Project that I began playing with in 2010 when my work was more focused on architecture and architectural ornament in architecture, in particular churches, theatres and museums. I was working with two paintings that Google had scanned at the Prado Museum, Las Meninas by Velazquez and L’ Immacolata Concezione by Tiepolo. Through using the software I really started engaging with the paintings themselves.

Another thing that has really inspired my work over the years has been the work of photographer Andreas Gursky. I like how it presents iconic images of contemporary society in a way that’s so far removed how we normally look at them. This is something that really fascinated me, trying to separate that object from the lived experience of looking at the object.

So in a way you went from exploring paintings within architectural space to exploring the architecture of paintings themselves?

Yes, absolutely, because in the end the paintings are explored as landscapes or spatially. The painting becomes a site for architectures to be built upon. That’s how I think about architecture, in terms of sites. It’s just another way of experiencing a space; another way of seeing.

– Interview by Fiona Shipwright

Iconographies, is on show at NOME Gallery, Berlin until March 5, 2016.

– Quayola is a visual artist based in London. He investigates dialogues and the unpredictable collisions, tensions and equilibriums between the real and artificial, the figurative and abstract, the old and new. His work explores photography, geometry, time-based digital sculptures and immersive audiovisual installations and performances. quayola.com

Strata #3 - Excerpt from Quayola on Vimeo.