-

Magazine No. 37

Zaha

-

No. 37 - Zaha

-

page 02

Cover

-

page 03

Editorial

-

page 05 - 11

Hadid

An interview with the architect Zaha Hadid by Sophie Lovell

-

page 12 - 21

Fluid Freedom

Zaha Hadid’s Four Decades of Breaking the Box by Aaron Betsky

-

page 23

The Asymmetric Mirror

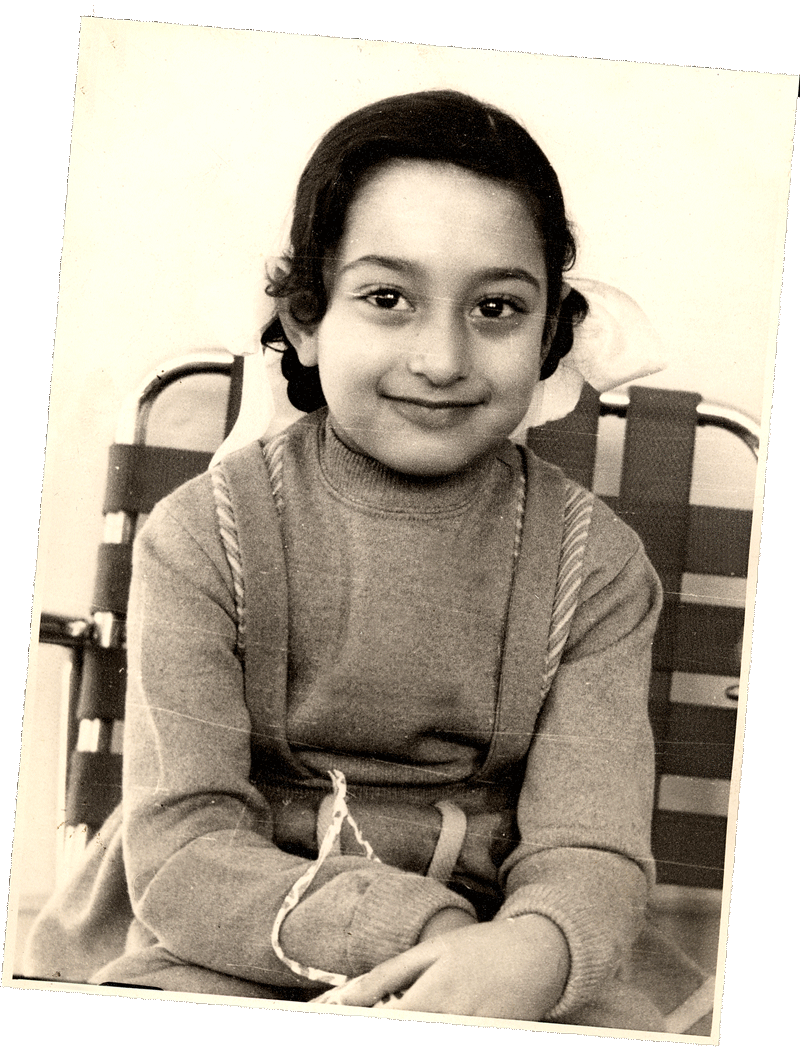

The young Zaha

-

page 24 - 27

A Planet in its Own Orbit

On being Zaha by Bernard Tschumi

-

page 28 - 30

Calculated Constructs

Greg Lynn on the formulas generating success at ZHA

-

page 31 - 37

Under Construction

Photographer Hélène Binet's view of Zaha Hadid's architecture

-

page 38 - 43

The Aura Comes Later

An interview with Rolf Fehlbaum of Vitra

-

page 44

Zaha at the AA

Student years in London

-

page 45 - 49

A Fine Sculptural Mind

The Aesthetics of Zaha Hadid by Jonathan Bell

-

page 50 - 52

On a Road to Nowhere

Moving through the MaXXI in Rome by Rob Wilson

-

page 53

Pet Shop Girl

The Nightlife World Tour set 1999-2000

-

page 54 - 60

Brendan Cormier’s

Focus on Zaha Hadid Design

-

page 61 - 64

Wonderfully Dishonest

Impressions of the Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku by Vladimir Belogolovsky

-

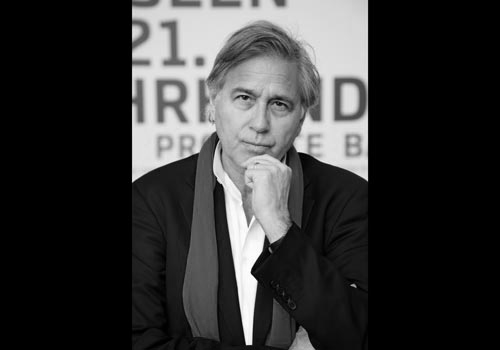

page 66 - 70

In the Photo Booth with...

Patrik Schumacher

-

page 71 - 73

Mending Space

Andreas Ruby admires the stitching skills of Zaha Hadid

-

page 74

Further Reading

-

page 75

Next

Death

-

-

uncube's editors are Sophie Lovell (Art Director, Editor-in-Chief), Florian Heilmeyer (fh), Rob Wilson(rgw) and Fiona Shipwright (fs); editorial assistance: Sara Faezypour (sf); graphic design: Lena Giovanazzi, graphic assistance: Diana Portela.

uncube is based in Berlin and is published by BauNetz, Germany's most-read online portal covering architecture in a thoughtful way since 1996.

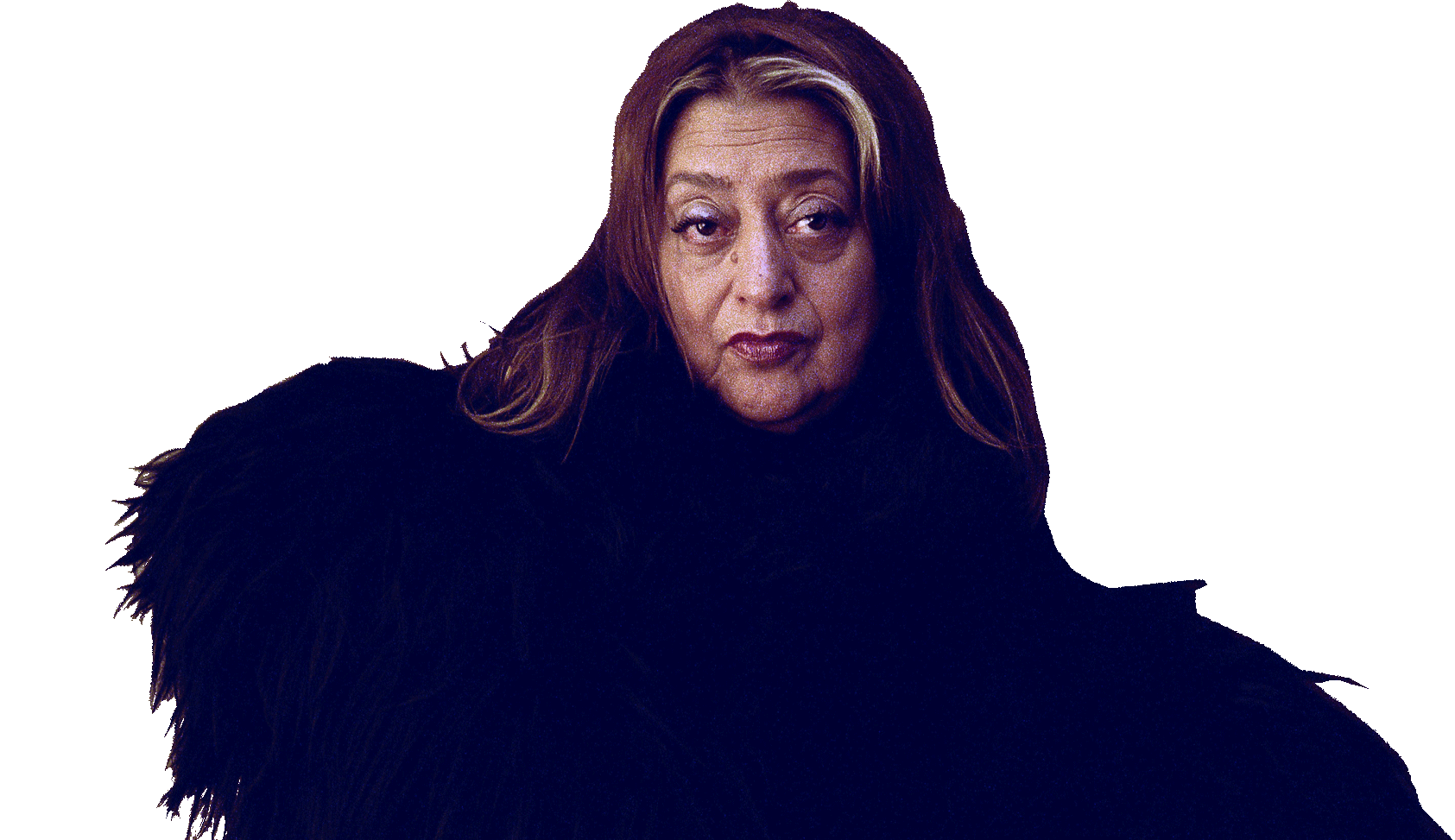

Why, you might wonder, is uncube dedicating an entire issue to one of the most controversial figures in architecture today? Dame Zaha Hadid polarises opinion like no other, yet here is a woman who has won every top award worth having in her discipline for her work which undisputedly pushes the technical and formal boundaries of building.

To mark the occasion of her 65th birthday in October 2015 we have consciously put aside for a moment the headline news fodder about working conditions in Qatar, Tokyo Stadium mudslinging and interview fiascos, that you can read about everywhere else, to focus on the actual architecture.

Issue no. 37 is a portrait of a singular architect whose star has burned a glorious path from her birthplace in Baghdad, through the unbuilt/unbuildable wilderness years, to running a 400-strong office translating her unmistakable forms into the built environment all over the planet.

Love her or hate her, one thing’s for sure: there ain’t nothing like this Dame!Cover image: Zaha Hadid. (Photo: Gautier Deblonde); this page: extract from the “Science Gallery Museum” concept visualisation. (Video courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects)

-

![]()

![]()

An Interview with the architect Zaha Hadid

by Sophie Lovell

-

![]()

aiting for Zaha is what happens to many that come into her orbit. She is after all an international figure heading a global concern operating dozens of projects worldwide. But as much as she is a leading starchitect she is also someone that polarises opinion like no other – and far beyond the realm of architecture. Why is that actually? In seeking to find out, uncube’s Sophie Lovell found patience paid off and encountered a reflective architect deeply involved in her work in all its facets.

Photos: Gautier Deblonde

-

All high-profile architects experience criticism at some time or other, but do you feel you have had more than your fair share? Do you feel you are sometimes misunderstood?

I’m a woman. I’m an Arab. I’m an architect. Biology and geography define the first two; the third has taken forty years of hard work. But hard work is not always enough. For a large part of those forty years, some of the biggest difficulties that I faced were brought about not by my work, but by my existence as a woman, or as an Arab, or indeed, as an ‘Arab Woman’. Ignorance and injustices, large or small, blatant or subtle, deliberate or – and perhaps worse – casual, not even recognised by their perpetrators.

I’m Iraqi; I live in London; I don’t really have a particular place - and can say from my personal experience, it is actually very liberating. Perhaps it was my flamboyance rather than being a woman that was the reason I didn’t fully fit into the culture at hand. I think, on one hand, it’s made me much tougher and more precise – and maybe this is reflected in my architecture.

Looking at your work, the diligence you apply in preparation by hand, in terms of sketches, drawings or paintings for each new project has been particularly noticeable. Do you have a routine or a regular path that you follow when approaching each new project concept?

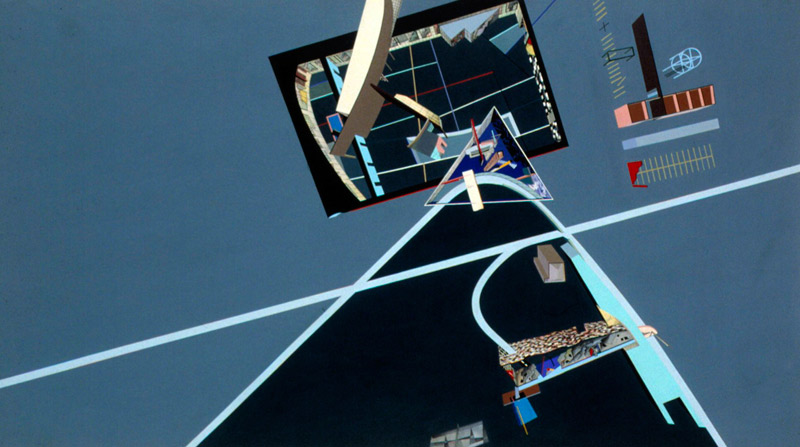

Painting formed a critical part of my early career as the design tool that allowed us the intense experimentation in both form and movement - leading to the development of a new language for architecture. The painting was always a critique of what was currently available to us at the time as designers – as 3D design software didn’t exist. There has been a complete shift in the last, say, thirty years - to now doing some projects only on the computer. -

![]()

My paintings really evolved 30 years ago because I thought the architectural drawings required a much greater degree of distortion and fragmentation to assist our research - but eventually it affected the work of course. I’m not a painter - I have to make that quite clear.

I can paint - but I’m not a painter - as the paintings we created were always part of the research for our architectural projects. The paintings I’ve done are very important to me and if I did them again I’d do them in a very different kind of way, but they were very important at the time.

In the early days of our office, the method we used to construct a drawing or painting or model led to new discoveries. We sometimes did not know what the research would lead to – but we knew there would be something, and that all the experiments had to lead to perfecting the project. And these are the journeys that I think are very exciting, as they are not predictable.

The design processes in your projects over the years could be seen to have shifted from extremely warm, visceral, hands-on skills to a colder, machine-calculated and drawn, hands-off discipline. Would you agree? How does one maintain the warmth and vivacity in parametric design?

It is a different kind of operational psychology today.Previously, in an architect’s office, you’d have each individual do almost everything: make a model, design, answer the phone or make a slide presentation. Now, you have people who specialise in all the different aspects of the design and construction process, so we’ve worked hard to establish a collective research culture in our office where many talents can feed off each other’s ideas and experience.

The developments that computing has brought to architecture are incredible, and as such, the work is able to handle the much greater complexity and flexibility that clients require today. Computing has enabled an overall intensification of relationships - both internally within the buildings as well externally with the context.

I am, however, concerned that no one today really knows how to draw a plan. It took me 20 years to convince people to do everything in 3D, with an army of people trying to draw the most difficult perspectives, and now everyone works in 3D on the computer – but they think a plan is a horizontal section – it’s not. The plan really needs organisation via a diagram. -

You had an exhibition entitled “Form in Motion” in the US in 2012. Can you explain how important motion is to you in your work and how it differs, say, from the futurist notion of the representation of “speed”.

I’ve always been interested in how our movement through space affects architecture. As in the frames of a film: not seeing the world from one particular angle, but having a more complex view. We view the world from so many perspectives – never from one single viewpoint – our perception is never fixed. This movement through space is very critical in all buildings – which also impacts our perception of time and the relationships we establish with our built environment. It differs from the pure perception of speed.

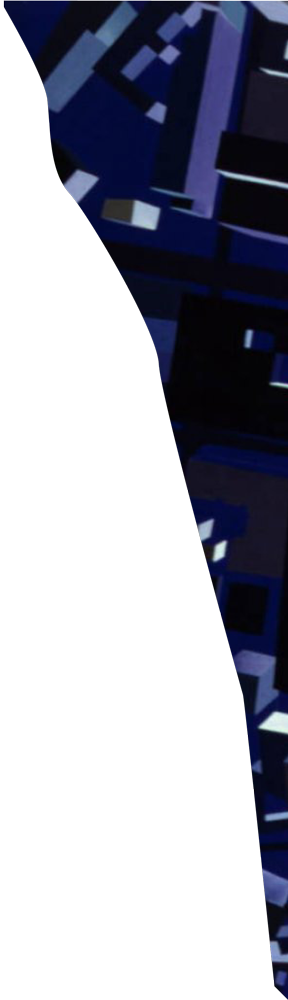

For example, in our Kartal masterplan design for Istanbul, located in a large derelict industrial area to the southeast of the city on the Marmara coast, we established a fluid grid which builds up over time.Sections of the grid develop as an entire plot or only at the intersections; it is fluid in that it changes in time, programme and space. This gradation allows a process of ‘incomplete composition’, where a project grows organically over time, but looks and feels complete at any given point in its evolution.

You are mostly famed for your stand-alone cultural projects but more recently I notice, there are housing projects as well, such as the new development in Milan. What in your view is the extent of responsibility for an architect in terms of where their building ends and the surrounding urban, rural or social fabric begins?

Architecture can carry within it an inherent sense of vitality and optimism; the ability to connect communities and build their futures. Ecological sustainability and social disparity are the defining challenges of our generation, and an architecture of inclusivity offers solutions to these key challenges. -

As an architect, your client is no longer a single person or type of person, your client is everyone. All buildings should have a civic component. Even a commercial high-rise building should offer a civic programme – public spaces in which people can connect with each other and use as their own. Developers in both the public and private sectors must invest in these public spaces. They unite the city and tie the urban fabric together.

What else needs to change?

There has been a move in many of the world’s cities over the past years towards walled, private spaces. As architects, we must react to this. Over many centuries, architects have been trying to liberate the city, to open it up, to make our cities more porous and accessible. Building these gated communities within the city, like mini Kremlins, is a huge step backwards; it is a very archaic way of living.

Part of architecture’s job is to make people feel good in the spaces where we live, go to school or where we work - so we must be committed to raising standards.There’s enough total wealth today that all people should have a good home - not just the very rich.

How important is it for you to consider the entire lifecycle of your buildings – where materials come from and where they go after its natural life is ended and how do you feel about the idea of your buildings being adapted, and changed in the future?

We certainly consider the requirements of adaptability for the long term use of any project. We cannot predict the future, but we can always try to anticipate it.

Architecture does not follow fashion, political or economic cycles – it follows the inherent logic of cycles of innovation generated by social and technological developments. Contemporary society is not standing still, and its buildings must evolve with new patterns of life to meet the needs of its users. I believe what is new in our generation are the much greater levels of social complexity and connectivity.![]()

-

Contemporary urbanism and architecture must move beyond the architecture of repetition and compartmentalisation, towards an architecture of flexibility that addresses the complexities, dynamism and densities of our lives today.

You have an extraordinary way of pushing not only forms, but materials as well to their limits. Have you at times had to wait for material development to catch up in order to realise what you really want to do?

We have a whole section of our office researching new design and construction techniques. The office maintains this on-going research and experimentation - and there is always a lot of collaboration with engineers and with people doing experiments with materials to work on new discoveries and push them into the mainstream for the wider benefit. What is interesting now is a new worldwide collective research culture in architecture that allows many diverse talents and innovative ideas to feed into each other’s ideas and disciplines.

What recent material breakthroughs particularly excite you and which ones are you still waiting to happen?

One such innovation would be sophisticated architectural skins that can take almost any shape and have the structural, weatherproofing, and insulation properties compressed into a single layer and can be easily fabricated and assembled anywhere. 3D printing is also opening a totally new universe of possibilities: complexity will no longer be restricted by the need for simplification or design rationalization – enabling the cost of a wall to be defined by its volume and weight and not its shape (building a curved wall will be no more expensive than building a straight wall), allowing the architecture to be much more articulate and rich.

Applying 3D printing in the construction industry can greatly reduce the energy consumption of a build. The energy used to transport construction materials to site – and material waste on-site - are considerable. By 3D printing only the material we need, there will be no offcuts and no excess of materials. The designs will also be more sustainable. For example, potentially adding shading where needed, and calibrating windows and openings to give the best possible performance. We already address these aspects of sustainability in design, but requirements to minimise costs often demand repetition and standardization. In the future, with 3D printing such constraints will no longer be necessary. I -

![]()

Zaha Hadid’s Four Decades of Breaking the Box

by Aaron Betsky

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

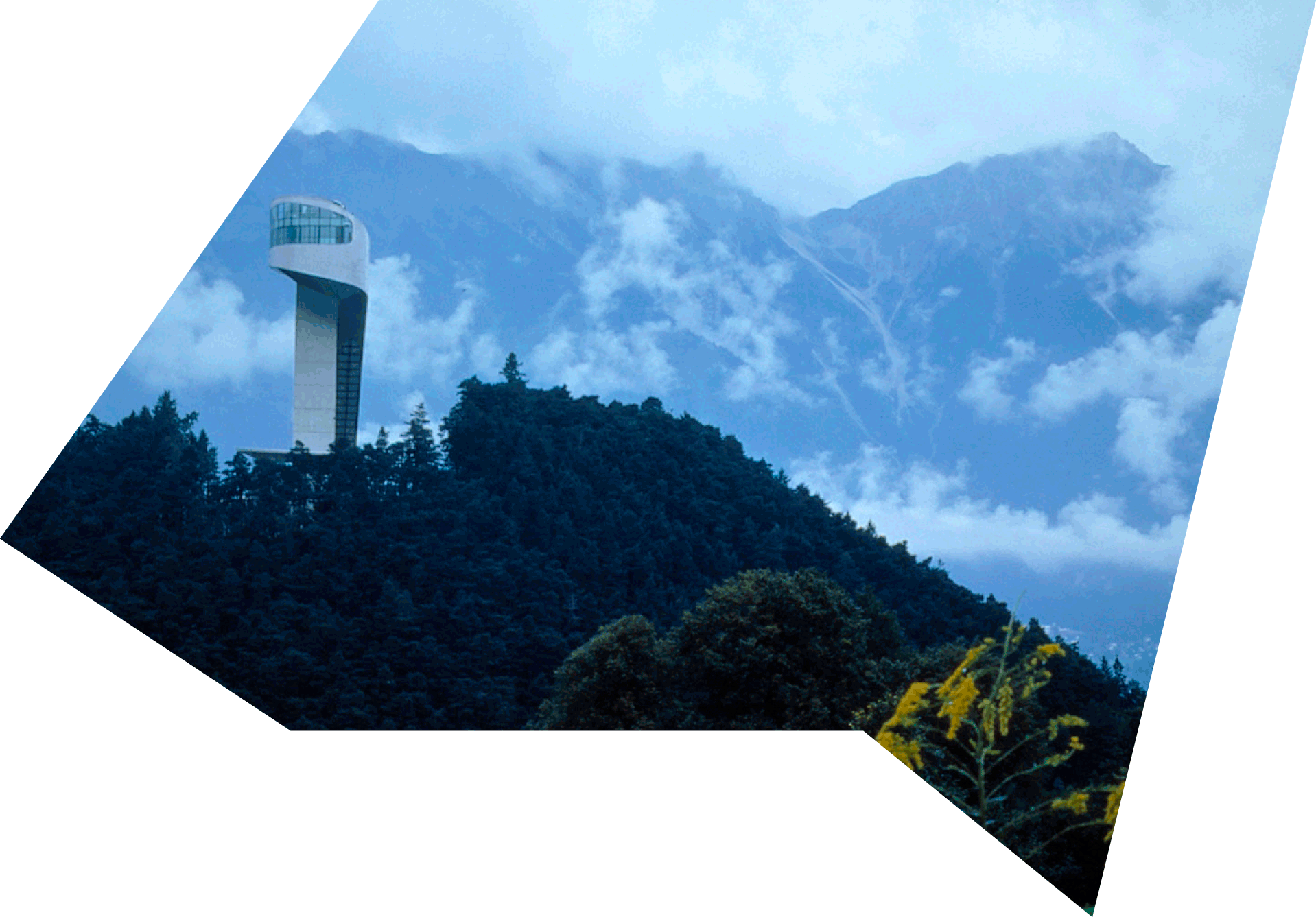

Hadid’s architectural career has been a quest to translate the continual movement of her fluid forms into architecture, says Aaron Betsky, and in doing so she has changed the nature of the discipline.

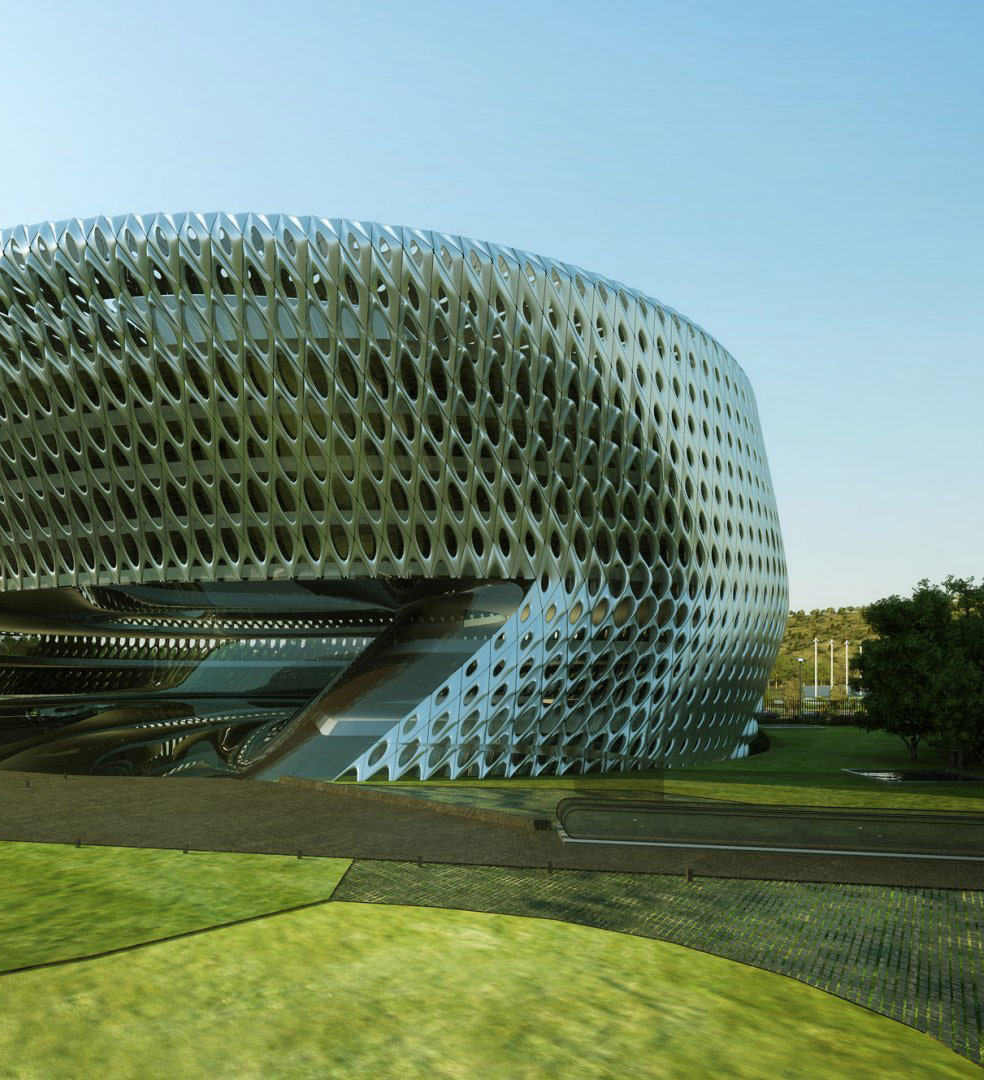

Zaha Hadid’s career in architecture has traversed the terrain of modernism from the retroactive activation of the Suprematist notion that we could defy gravity, coherence, and type by the dissolution of form, through the creation of fluid forms that slithered away from definition and closure, and then into the realm of parametric modelling that melds architecture, landscape, and human behaviour into forms that are even more elusive. As such, her work has been central in the movement of architecture away from the making of objects and towards the tracing and tracking of human activity, with the aim of creating a profound modelling of form around our social selves.

![]()

![]()

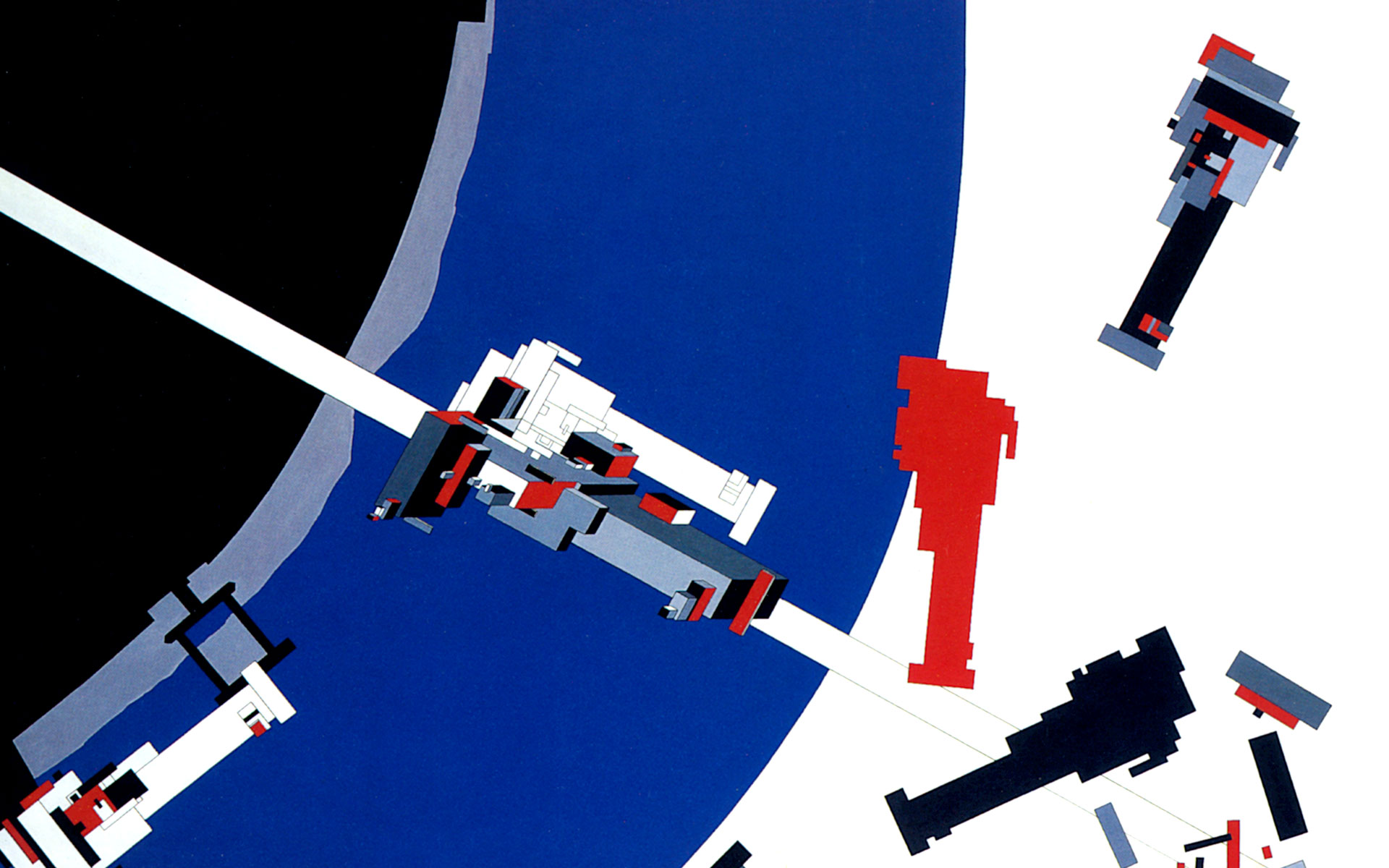

Previous page: painting from “Malevich’s Tektonik”, Zaha’s graduation thesis.

(All images courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects; collage by Lena Giovanazzi)

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

When Hadid first came on the scene, the battle waging about architecture, at least in academic circles, was still between whether the object should – as the so-called “greys”, such as Charles Moore and Michael Graves, thought – be defined by either the panoply of classical elements academic architects had recently rediscovered, or cloak itself in the familiarity of a vernacular; or – as the “whites” such as Peter Eisenman and Richard Meier, felt – be abstracted to the point of disappearance. Students and teachers at London’s Architecture Association (AA), many of whom – like Hadid – had became associated with the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, instead proposed blowing the object up. They saw architecture, pace Frank Lloyd Wright and the Russian architects of the post-Revolutionary period, as breaking open the box.

Dame Hadid broke the professional box as well, becoming the most prominent woman and only person of Arab descent to make a mark in architecture at the turn of the millennium. Although such a professional achievement might seem separate to her work, it’s been as important in changing the nature of the discipline as her built forms.

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

By the time Hadid had established her own office several years after graduating from the AA, she became one of the central figures in what critics such as Mark Wigley called “deconstructivism”: a more profound refusal to build coherence or, in some cases, even build at all, by architects who saw their work as a re- and misreading of the past, of physical context, and of the conventions of communication. Wigley canonised his interpretation of Hadid’s work in the exhibition Deconstructivist Architecture that he curated with Philip Johnson at MoMA in New York in 1988, and in which her work featured prominently.

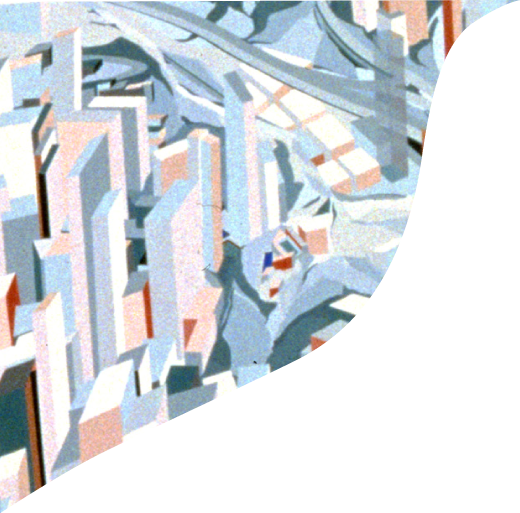

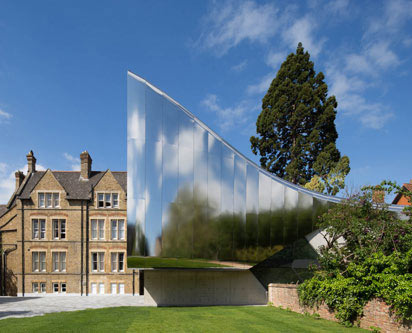

When Hadid finally began to build, first in Berlin and Weil-am-Rhein, then in Cincinnati, and soon around the world, she, like many of her fellow graduates of the late 1970s and early 1980s wars to resuscitate modernism, such as Wolf Prix of Coop Himmelb(l)au, Bernard Tschumi, and Daniel Libeskind, had to confront questions over how her theoretical and aesthetic position could be elaborated while creating objects that met functional, technical, and economic needs. Her answer was to propose spaces and forms that unfold in spiralling movements out of the landscape. The result, as Hadid saw it, would be continual movement in which the distinction between inside and outside, between public and private, and between enclosure and openness, would disappear.

The advent, during the mid 1990s, of sophisticated computer-aided visualisation and construction tools made the translation of this quest for fluid form into buildings, much more possible, although, at least until fairly recently, the construction of her firm’s designs have often acted more as promissory notes for such free-form design, as their construction has not always living up to the idea.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

Aaron Betsky is a curator, critic and writer on architecture and design. In 2015 he became the new dean of the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, which has twin campuses at Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin and Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Betsky was born in Missoula, Montana, USA and grew up in The Netherlands. He graduated from Yale University with a BA in History, the Arts and Letters in 1979 and an M.Arch. in 1983. He then taught at the University of Cincinnati from 1983 to 1985 and worked as a designer for Frank Gehry and Hodgetts & Fung. From 1995 to 2001 Betsky was Curator of Architecture, Design and Digital Projects at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art before moving back to The Netherlands to become the director of the Netherlands Architecture Institute in Rotterdam (2001-2006). From 2006 to 2014, he was the director of the Cincinnati Art Museum, during which time, in 2008, he was also the director of the 11th Exhibition of the Venice Biennale of Architecture.

Betsky has written numerous monographs on the work of late 20th century architects, including I.M. Pei, UN Studio, Koning Eizenberg Architecture, Inc., Zaha Hadid and MVRDV, as well as treatises on aesthetics, psychology and human sexuality as they pertain to aspects of architecture, and is known for his key contribution to a spatial interpretation of Queer theory.

In last few years, Hadid and her office have shown themselves more than capable of creating exhilarating forms. Unlike the recent work of some other members of the generation shaped by the events of ’68, who have built up large building practices, she continues to create forms that are startling in their openness and radical in their formal expression.

Since the early 2000s, her work has also extended to the creation of objects and even fashion accessories. Rather than seeing these as afterthoughts to her build work, as most other architects do, they are part of her continual search to rethink the personal and the social body, in such a manner that design breaks down physical, political, sexual, and economic barriers.

Most recently, her partner at Zaha Hadid Architects, Patrik Schumacher, has proposed that architecture can go even further in moulding itself to social movement by using the computer to model and predict this movement, with the intention of creating spaces and surfaces that allow for a variety of different activities. If the studio proves able to take this approach far enough, such an approach promises to allow for the creation of buildings whose adaptability to human action and social interaction would make their formal resolution appear not just the result of an aesthetic development from floating planes to snaking blobs, bulging prows, and Moebius-strips of space, but as the fulfillment of a desire to free architecture from its role as the built affirmation of the social, economic, political, and physical status quo.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

-

The Asymmetric Mirror

Zaha tells of how, as a girl, she grew up surrounded by modernist houses in a garden suburb of Baghdad, her parent’s 1930s house filled with “funky” 1950s furniture.

When her parents refurnished the house they commissioned new furniture from a workshop in Beirut: all angular, modernist and chartreuse in colour. In particular, for Zaha’s room there was a new asymmetrical mirror, with which she was thrilled – sparking a lifelong love of asymmetry. After reorganising her room around her new furnishings, Zaha’s cousin saw the result and asked her to do the same for her bedroom too. Then her aunt asked her to redesign her bedroom and so a career began... I (rgw)![]()

Zaha aged six in Baghdad, 1956. (Photo courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects)

-

![]()

![]()

A Planet in its Own Orbit

On being Zaha

By Bernard Tschumi

On the occasion of her 65th birthday, fellow architect and educator Bernard Tschumi, who has known Hadid since their times at the AA in the 1970s, ruminates on the uncompromising approach and objective qualities that both inspire and define her.

-

![]()

At a lecture at Columbia University in the early 2000s, a student asked Zaha Hadid if she felt designing was harder or easier now that she was a “brand”. “A lot harder,” Zaha replied, without the slightest hesitation. Both the question and its answer have echoes of a larger predicament faced by all the main figures of architecture throughout history. Is Zaha a unique, lone, irreplaceable, and sometimes even tragic figure or, on the contrary, is she part of the spirit of the time, a zeitgeist figure, an undaunted trendsetter showing the shapes of things to come?

One always wonders if, for someone whose work seems to flow seamlessly, in which idea and form converge and often seem to merge in one single motion of delight, whether some projects have in fact presented more of a challenge for their creator than first meets the eye.Remember the Cardiff Opera competition (1994), in which her winning “String of Pearls” entry triggered a long and embarrassing debate about whether the gender and nationality of the winner might disqualify her from building the opera – a project that was then never built. Or the more recent Guangzhou Opera House (2003), where the difficulties of building a radical concert-hall configuration and stunningly fluid circulation spaces clashed with the limitations of budget, technology, and national focus before, during, and after construction. Unless they are purely commercial undertakings, virtually every architectural project is a fight and entails battle, at any time or place in one’s career.

![]()

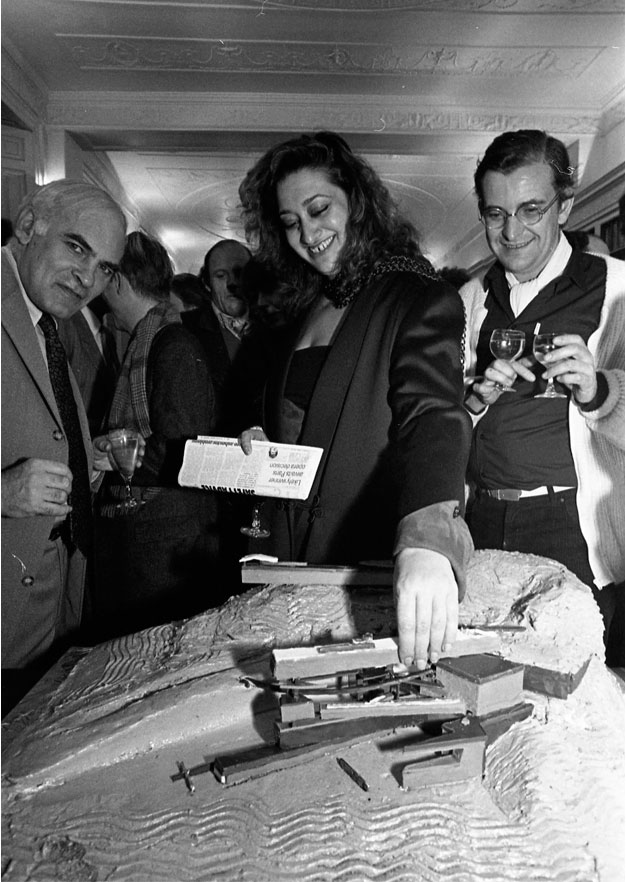

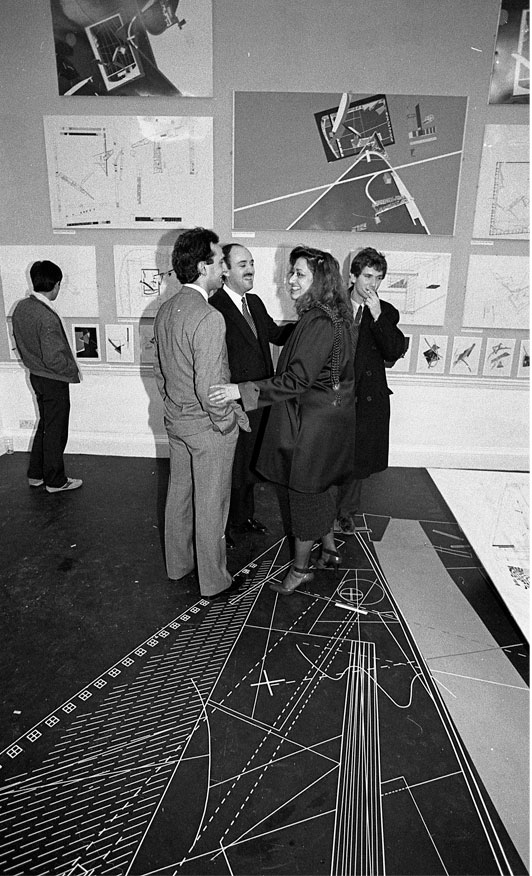

Zaha at the opening of her “Planetary Architecture II” exhibition at the AA, 1983.

(All photos © Architectural Association Photo Library, unless otherwise stated)

![]()

-

![]()

Left to right: Bernard Tschumi, Helmut Swiczinsky, Wolf D. Prix, Daniel Libeskind, Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid, Mark Wigley. (Photo: © Robin Holland)

»If Zaha was, as Rem Koolhaas famously remarked, a planet in its own orbit, she is uncompromising on Earth.«

-

Bernard Tschumi (*1944) is the principle of the firm Bernard Tschumi Architects (BTA), which he established in Paris in 1983 with the commission for the Parc de la Villette, a 125-acre cultural park there. In 1988 the firm opened its head office in New York. Since then, projects have included the new Acropolis Museum; Le Fresnoy National Studio for the Contemporary Arts in Tourcoing, France; the Vacheron-Constantin Headquarters in Geneva; The Richard E. Lindner Athletics Center at the University of Cincinnati; two concert halls in Rouen and Limoges, and architecture schools in Marne-la-Vallée, France and Miami, Florida, as well as the Alésia Archaeological Center and Museum in France. He is a Professor in the Graduate School of Architecture at Columbia University, New York.

tschumi.com

Zaha has been, throughout this extended process, both dedicated and determined about her shapes in a way that transcends the, often pedestrian, “shape-ism” she inspired. If Zaha was, as Rem Koolhaas famously remarked, “a planet in its own orbit”, she is uncompromising on Earth. Think only of her legendary battles at the AA, as when Zaha and Alvin Boyarsky argued for four hours, at times in anger, over whether the dinner table for an event in her honor should be circular or rectangular, its shape being of paramount importance to Zaha. Shape or semantics, trivial or defining? (After all, a major peace treaty involving China, the US, and North and South Vietnam did depend on first agreeing on the shape of the negotiating table.) Look to the cherished artefacts she carries, wears and owns that have defined her image and sensibility over the years – the notorious “titty handbag” in the shape of a woman’s breasts by Jean-Paul Gaultier and the amorphous black furry bag (Is the story of Zaha’s handbags one that should be investigated, documented and archived?), the fluid pleated fabrics and artfully encrusted silks, the curvilinear Murano vases in riotous colors, and so many other objects and envelopments that have made her personal aesthetic and existence a mode of unique forms of continuity in space.

Zaha’s objective “creation myths”, defining attributes, and trajectory – which encompasses an effort to transmute these uniquely fluid forms of beauty into viable, articulate spaces – are like no other architect’s. May her 65th year see more uncompromising production and complex reflection on the objective qualities that at once inspire and define her. I![]()

![]()

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

Calculated Constructs

The formulas generating success at ZHA

By Greg Lynn

![]()

As a fellow Professor at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, architect Greg Lynn sees the technical transformations in the digital workflow of Zaha Hadid and Patrik Schumacher’s office as ten years ahead of the game.

-

It is too easy to attribute the success of Zaha’s office to her skill with shapes, her charm and her tenacity; these are the explanations most often heard surrounding her achievements. However, like Frank Gehry, she has invested greatly in technology and her contribution to the field of architecture may well be primarily in technical and commercial terms than in shapes and formal vocabulary.

I‘ve been a Professor at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna alongside Zaha Hadid and Patrik Schumacher for nearly fifteen years. During this time, I’ve observed their engagement with technology, urbanism, construction and culture through their teaching and the work of the office. Their interests often precipitate formal results but before shapes are drawn or modelled there is always a lengthy, often quantifiable, analysis. I’ve now realised that the purpose of the analytic phase is manifold; but one of the primary functions is to motivate decisions within a digital medium predicated on numbers and dimensions.

More formidable than either her design, interpersonal or psychological strengths is this deep knowledge of, and curiosity in, digital design and construction. She and Patrik were among the first offices to begin working with Gehry Technologies and have alumni from it in leadership roles on numerous project design teams. This is important to recognise as Gehry and Hadid are several years, if not a decade, ahead of the competition when it comes to embracing a digital workflow from design through construction.

Previous page: GIF from the Arum Video,Venice Biennale, 2012. This page: Space frame modelling of the Dongdaemun Design Plaza, 2013, Seoul. (Images courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects)

-

Greg Lynn is an architect and innovator specialising in redefining the medium of design with digital technology as well as pioneering the fabrication and manufacture of complex functional and ergonomic forms using CNC (Computer Numerically Controlled) machinery. He was born in 1964 in Ohio, graduated from Miami University of Ohio with degrees in both architecture (Bachelor of Environmental Design) and philosophy (Bachelor of Philosophy) and later from Princeton University where he received a graduate degree in architecture (Master of Architecture).

Lynn is now a Studio Professor at UCLA’s school of Architecture and Urban Design where he is currently spearheading the development of an experimental research robotics lab. He is also Davenport Visiting Professor at Yale School of Architecture.

Lazy critics often invent excessive costs, prolonged schedules and even construction fatalities to describe her work but in fact the reverse is the case. Next time an architect making a pretty box tells you Zaha’s buildings are expensive please ask them where they are getting their information. Odds are they’re trying to explain why they themselves are so far behind in the technological transformation of the design and construction industry. Whenever I hear the costs and schedules for her buildings I am amazed at how quickly and affordably they are being built, often in places without a mature construction industry. It is difficult to compete with the speed, efficiency, costs and fees that her firm requires; far less than the retro-modernist architects who rely on old world artisanal methods of construction, luxurious materials and excessive labour to bring value to their work. Zaha’s office is competitive not because of her personality but due to her embrace of innovation. This is the only explanation for the rapidity of their success in the Middle East, Russia and China where few other architects are able to operate commercially.

Over the last ten years the impact of Patrik on the office can’t be underestimated as he has focused more and more on a parametric model of practice where quantifiably discrete values can be assigned to every aspect of a building’s design, engineering and construction. In saying that their office is a decade ahead of their competitors is to say that inevitably other architects will become increasingly like them in how they practice; not in the style of architecture but in their use of technology. Patrik is maniacal about converting architects to parametricism in theory but it may be unnecessary as it’s happening through practice. Perhaps no one is scurrying further down the rabbit hole of digital sensibility than Patrik, a fact which provides a better insight into their work than the familiar personality profiles, stylistic musings and metaphorical comparisons employed by today’s journalists.

I’ve always admired Zaha’s commitment to change in the field over and above all other concerns personal and professional. It happens that my particular interest is in her ability to take up digital technology. Exactly like our friend and colleague Frank Gehry her impact might very well be on how practice is transformed through knowledge and technology. This is not to minimise the power of the shapes and spaces but to point out that there is significant innovation behind them. I

-

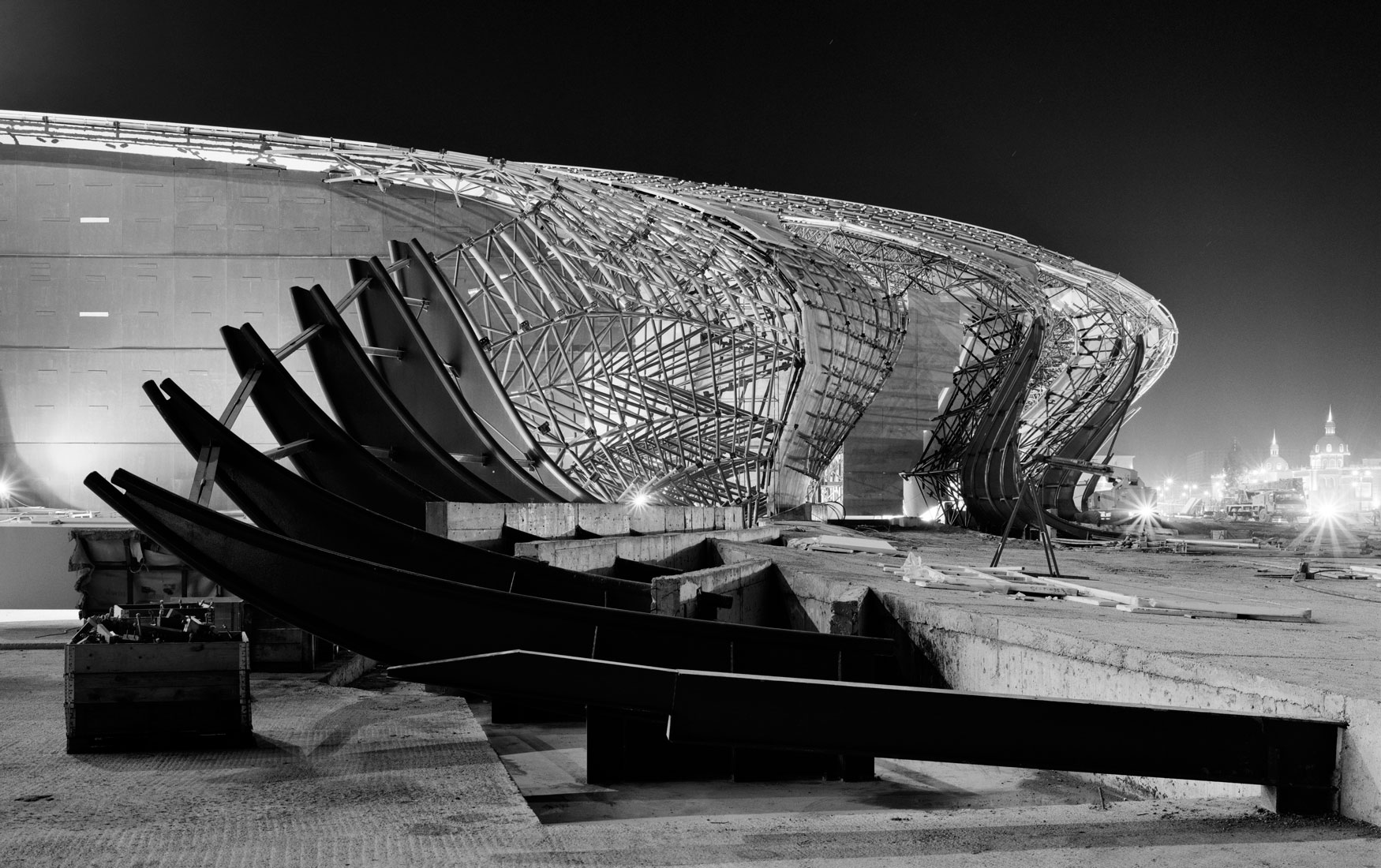

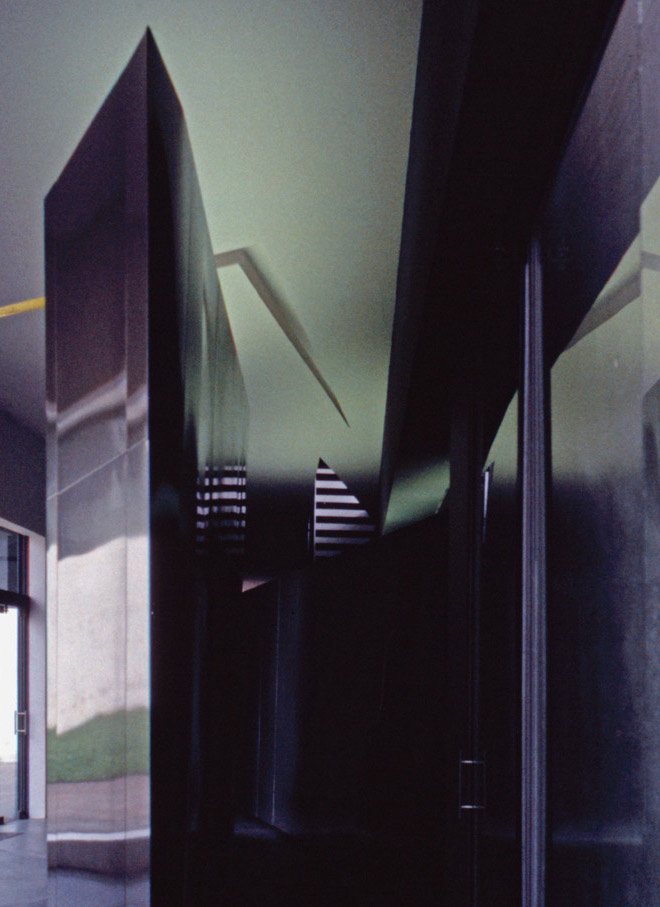

![]()

A photographer’s view of Zaha Hadid’s architecture

Photography and words Hélène Binet

-

There is perhaps no one outside the firm more familiar with Zaha Hadid’s built oeuvre than the architecture photographer Hélène Binet. For the past 30 years she has shot most of Hadid’s buildings, both completed and under construction. Here she has compiled her own selection for uncube from her many photographs of Hadid-under-construction, offering a glimpse behind the scenes and revealing the enormous effort involved to create her light and fluid forms. The quotes are taken from an extensive interview with Hélène Binet which you can read in full on the uncube blog.

Previous page: Heydar Aliyev Centre, Baku 2012; this page: Vitra Fire Station, Weil am Rhein, 1993

-

![]()

![]()

Phaeno Science Centre, Wolfsburg, 2003

»Whenever there is a project where Zaha is pushing the boundaries and limits of building technology and our imagination of what is feasible, and when there is a specific moment when this becomes visible on the site – then I would go there.«

-

»What I am looking for is this moment when technology is stretched to its limits and becomes clearly visible.«

Phaeno Science Centre, Wolfsburg, 2003

-

![]()

Heydar Aliyev Centre, Baku, 2012

-

![]()

Vitra Fire Station, Weil am Rhein, 1993

»There is an aesthetic in how a building is made, how you pour the concrete and assemble the steel, and I want to show the beauty of this moment.”«

-

Hélène Binet (*1959) comes from a Swiss and French background. She studied photography at the Istituto Europeo di Design in Rome and started working as regular photographer at the Grand Theatre de Geneva in Switzerland, where she “fell in love with the world of shadows and light”, as she once put it. She then moved to London where she slowly made her way into architecture photography, following the works of Daniel Libeskind, Peter Zumthor, Caruso St. John, Zaha Hadid, John Hejduk or David Chipperfield, some of these over many years. Binet has always followed her love of light and shadows, producing some of the most dramatic black-and-white-images of the buildings, which she portrays rather than documents. She also is an advocate of analogue photography and has worked exclusively on film right up until today.

helenebinet.com

»I see a strong sense of freedom in her buildings. They are not places to meditate, to sit and think in quietness. They are places to fly.«

Read the full interview with Hélène Binet on the uncube blog.

Port House, Antwerp, 2015

-

![]()

An interview with Rolf Fehlbaum, Chairman Emeritus of Vitra and commissioner of Zaha Hadid’s first completed building.

Interview by Rob Wilson

-

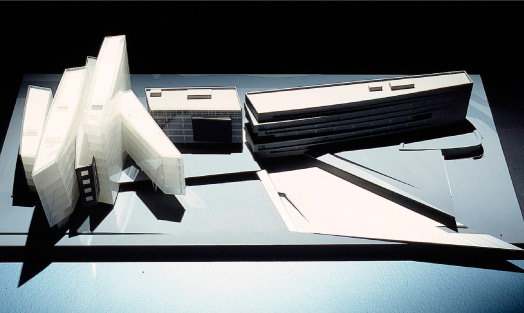

The Swiss-owned furniture firm Vitra has worked with outstanding designers ever since its foundation in 1957. Today, it is almost as famous for its collection of avant-garde buildings commissioned to house its works and production in Weil-am-Rhein, Germany, after a fire destroyed the original factory in 1981. In 1993 Zaha Hadid joined Nicholas Grimshaw, Frank Gehry, Tadeo Ando et al in the Vitra architecture portfolio with her fire station design that was modest in size but huge in its impact. uncube’s Rob Wilson talked to Rolf Fehlbaum about his decision to pick an unbuilt architect to join his stable of superstars.

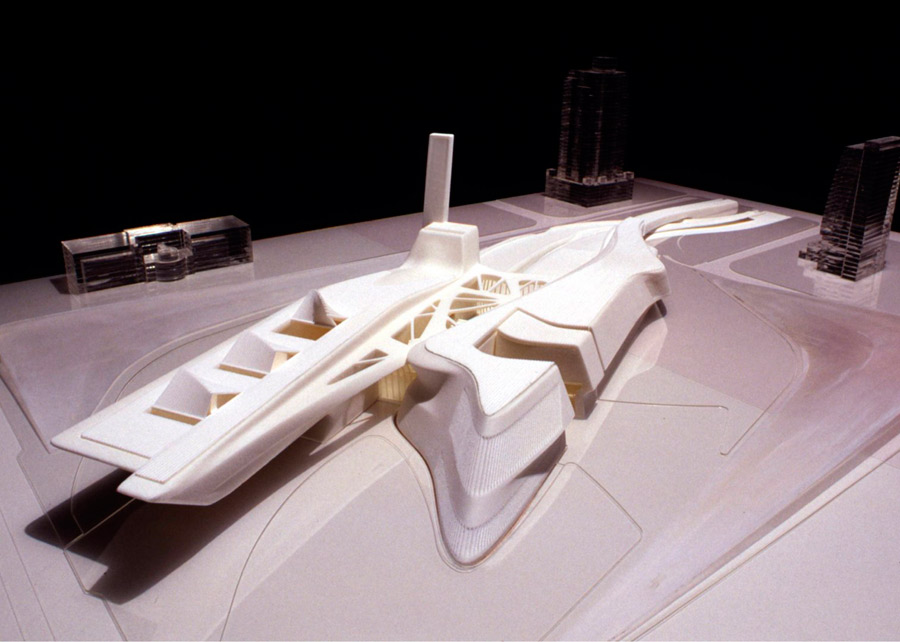

![]()

Previous page: painting of the Vitra Fire Station, 1990-1993. This page: building model. (Images courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects)

-

Hadid was fairly unknown when you commissioned her to build a fire station for you, how did you first come across her work?

I had read a conversation in Blueprint magazine between Zaha and Alvin Boyarsky on furniture, and I got very interested. I first contacted Zaha in late 1987 to work on furniture together. It was only in late 1988 that I asked her whether she would be interested in designing our fire station. And she was.

We worked on the building from 1989 to 1993, which is quite a long time for such a small structure. Zaha approached the task in a very vast way – not just making a building but developing a zone. It was a very elaborate process. I don’t know how many drawings and models she made. A lot of research into the whole environment went into the building: she took its lines from its surroundings, from the adjacent hills and up to the vineyards.Photo: Christian Richters

-

What was the design process like? Did you experience her as an easy or challenging architect to work with?

Easy and challenging: easy in that we got along very well; challenging in that Zaha’s ideas were new and different and the process of translating them into a building was demanding for everybody. Zaha has a totally independent mind. She approaches a task critically. So she didn’t just design a building but found the masterplan too mechanical and subtly changed the main axis as well. Like every good architect she questioned the brief and went beyond it. That’s what I’ve always enjoyed when working with great architects: they don’t just do what you ask for. Their questions and the discussions open your eyes to things you have not seen before. And what’s nice about being an independent client is that, if you think it’s worth it, you can always decide to give a project more time. It’s better than ending up with a building that’s not as great as it could have been.

You had been working with exceptional architects since the early 1980s and have collected some experience in this regard. How do you interpret your role as a client – do you see it as a creative one?

To an extent yes, but with a building it’s very different from the design process for a product. There you have a direct relationship with the designer, you in a way co-design the product if you are an active client. With a building that’s different because in the end it is always the architect designing the building. But in a good relationship one has to achieve an overlap between the fantasies of the architect and the fantasies of the client. A good client trusts the architect, but not blindly. A good client cares so much about the building that he or she gets involved, discusses, questions and in the end trusts. For the architect, I guess, nothing is worse than an anonymous or absent client. I am not saying it’s a creative role but it’s an important one.

Image courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects

-

![]()

![]()

Interior details. (Photo: Flickr/Robert Lochner, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

-

Rolf Fehlbaum, the eldest son of Willi and Erika Fehlbaum, was born in 1941 in Basel. After receiving his Matura diploma, he studied social sciences at the Universities of Freiburg and later in Munich, Bern and Basel. He completed his academic studies in 1967 and worked for a short time with the Vitra Company, the shop-fitting business founded by his parents. In 1970 he moved to Munich to work as an editor and producer for the Bavaria Film Company and from 1973 to 1977 he was responsible for education and training at the Bavarian Chamber of Architects. In 1977 he took over the management of Vitra.

www.vitra.com

Photo: Christian Richters

Yet the fire station no longer functions as a fire station. So was it really that functional?

Yes it was. I read once that we had to build a second fire station because the first one didn’t work. That’s ridiculous! The fire station worked very well, but after a few years the city offered a better service. At first we wanted to join the two fire forces, but theirs was fully professional, so we disbanded ours. Which left us with a great empty building, which we can now use for exhibitions and events, lectures and concerts. We use it all the time.

It is often seen as the project that kick-started Hadid’s career. Do you feel satisfied that your role as client was so important on that way to the top?

I am very happy that Zaha became such a force in architecture. But she was that before. She was an accomplished architect with a very strong presence before she built. She was not there to be discovered. I am also very happy that it is such a good building. It is not a beginner’s building at all. So yes, I am very happy that I could give her that opportunity, and that it helped start her career in the three dimensional world.

-

Zaha at the AA

When Zaha Hadid moved to London to begin her architectural education at the Architectural Association School of Architecture (AA) in London in 1972, the school was already in the throes of transformation under the new directorship of Alvin Boyarsky, who had begun shifting its focus to a more international view. It was at this time that Hadid encountered some of her most influential teachers, including Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis, who in 1975 with Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon Vriesendorp, went on to form the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) at which Zaha would become a partner. Known for its unconventional curriculum, the AA embraced new ideas and innovation, giving Hadid ample opportunity to explore and develop her own architectural language and ideas. In 1977 she won the AA Diploma prize and would go on to teach her own studio there until 1987. I (sf)

Zaha in the Pink Room at the AA, c.1975/76. (Photo © Architectural Association Photo Library)

-

![]()

The Aesthetics of Zaha Hadid

By Jonathan Bell

-

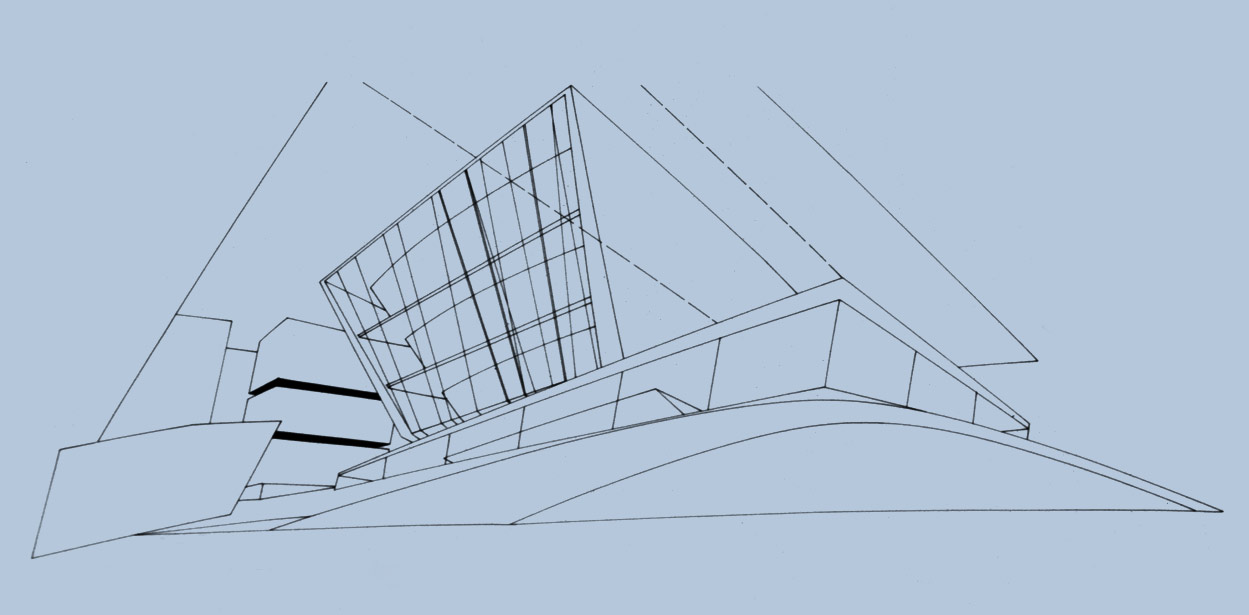

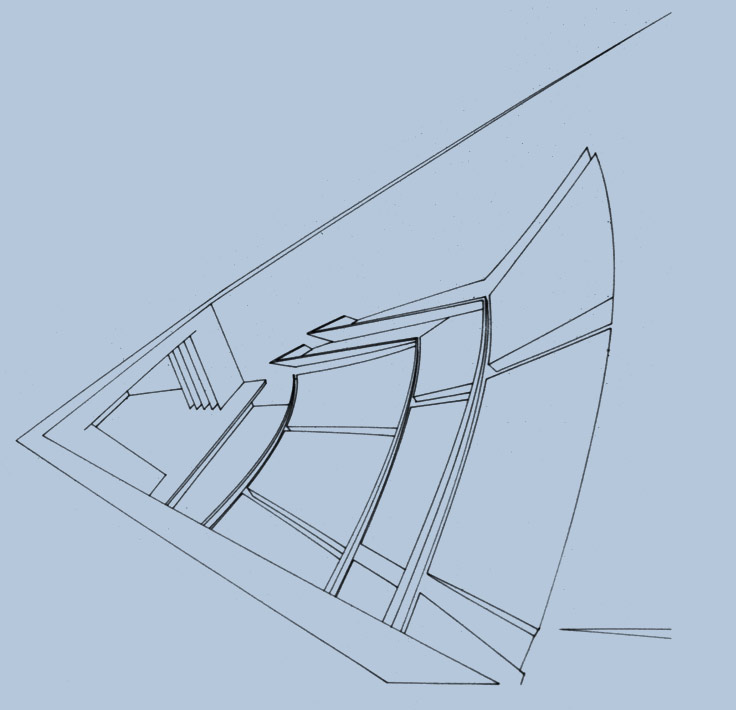

Zaha Hadid Architects is now a practice of over 400 employees renowned for its sophisticated computer-based design, but its founder has always drafted by hand. Architecture critic Jonathan Bell looks at Hadid’s exceptional sense of aesthetic form that has made her an artist among architects.

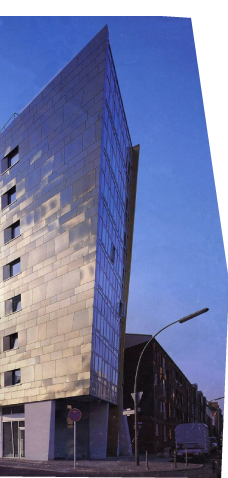

Previous Page: Site plan drawing for the Peak Leisure Club (unbuilt), 1982-83, Hong Kong. This page: Vitra Fire Station, 1990-93, Weil am Rhein.(All images courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects)

-

The aesthetics of the avant-garde in architecture is what has always drawn in the eye. It's what engages with the public and the city that surrounds it. Reams of theory and terabytes of data might underpin cutting edge architectural form, but the factor that shapes the way we perceive these buildings is pure and simple: aesthetic form.

Zaha Hadid is a very aesthetic architect. That is to say that the Iraqi-born British Dame of high design is an architect who can be defined almost entirely by form, despite the solid layers of theory and even more solid technological underpinnings that shape every building and product that comes out of her studio. From Hadid's earliest works, produced while a student at the Architectural Association in London, her formal adventurousness has been pushed to the fore. Naturally, in the days before digital and 3D printing, the best form of expression was the drawing, and Hadid's drafting stood out as exceptional, particularly the large-scale canvases she produced, depicting her buildings as facetted, deconstructed forms scattered across skewed landscapes.

These works brought her work to wider attention, most notably with a competition-winning entry for The Peak restaurant in Hong Kong in 1983, a work that still appears contemporary to our pixel-saturated eyes by dint of the extreme geometry of its forms and the boldness of the presentation; a cascade that slices across a deliberately distorted Hong Kong cityscape. -

![]()

![]()

Cardiff Bay Opera House competition entry, 1994-96, UK.

From the outset, Hadid's presentation transcended that of her peers. For the architectural press of the pre-digital era, this suggested it could be placed in only a few stylistic pigeon holes – the “paper architecture” of the perennially unbuilt (and possibly even unbuildable) or, more intellectually, the Deconstructivist School pioneered by Peter Eisenman and Daniel Libeskind. In hindsight, “Decon” existed at the juncture between post-modernism and the digital era. Although it was hard to define yet easy to recognise, it was Hadid who ultimately took the genre from the page and into built reality. With the Vitra Fire Station in Weil-am Rhein (1993), those exaggerated perspectives and vanishing points were suddenly made real, instantly crumbling the modernist relationship between form and function. The following year, the studio's winning entry in the Cardiff Bay Opera House competition seemed to consolidate Hadid's ascendance, but it was a false dawn and the project collapsed in acrimony. For a few years, Hadid was in the wilderness.

Throughout this period the studio's aesthetic sense evolved in parallel with emerging technology. Whereas Hadid's earlier works presented a physical, analogue interpretation of what might otherwise be considered impossible, the practice's emphasis on research and experimentation has reaped dividends in the way it translates organic form into architecture. In particular, this has manifested as a commitment to parametricism, an architecture generated from the brief, the site, the programme and the materials. In short, a parametric building is one that uses the intrinsic complexity of the many parameters that make up a building to express them in physical form.

More problematic, perhaps, is the way in which the practitioners of parametricism decry its association with traditional aesthetics. Patrik Schumacher, Hadid's creative partner, wrote a dense two-volume, 1,300-plus-page thesis, The Autopoiesis of Architecture, in which aesthetics get relatively short shrift, buried beneath near-impenetrable layers of theory. Yet Hadid has always presented herself as an artist, from the oil paintings and prints she undertook as a student to the more explicitly sculptural pieces she has created throughout her career as an architect. Parametricism seems to deny artistic intent, or at the very least obscures it. The sensuality of this architecture – for curves, kinks, bends and scoops are always in some respect sensual – is thus overshadowed by a misplaced determinism, almost as if its authors are afraid of engaging with the concept of beauty at all. -

Jonathan Bell is an editor, copywriter and design consultant. He has written about art, design, architecture and automobiles for many leading titles, including Wallpaper* magazine. His books include The 21st Century House (pub. Laurence King), Penthouse Living (pub. Wiley-Academy) and The New Modern House (pub. Laurence King).

Parametricism has its imitators, for as an approach it is just as total and all-consuming as the High Modernism of the 20s and 30s. Yet even slavish imitation falls somewhat short. Perhaps that's what Hadid's work is so good at reminding us, as her most successful buildings graduate from page to site with a satisfying robustness thanks to the physicality of concrete, steel and glass enhancing the twist and thrust of their forms. Linear, multi-functional spaces like the Evelyn Grace Academy school (2010) in south London, the jarring angles of the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum (2012) in East Lansing and the rippling facades of the CityLife Milano apartments (2014) in Italy all fulfil the promise of their plans. Regardless of technology, ideology or methodology, there is a fine sculptural mind at work.

Cardiff Bay Opera House drawings.

-

![]()

On a Road to Nowhere

Moving through

the MaXXI in RomeBy Rob Wilson

Uncube’s Rob Wilson finds flow-stopping beauty and fundamental flaws within Zaha Hadid Architects’ Italian museum – but also perhaps a fitting reflection of our times.

-

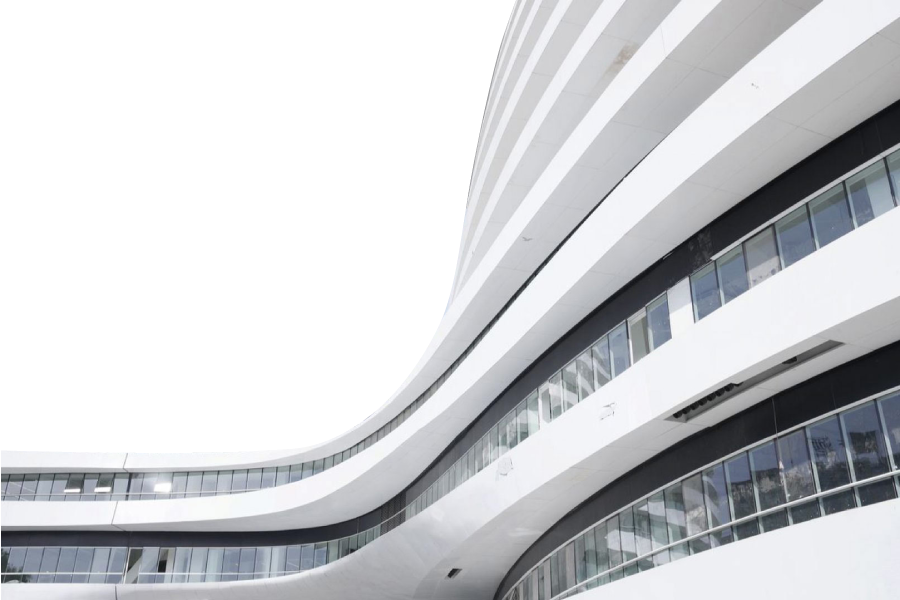

Opened in 2010 on the site of an old barracks after a twelve-year genesis, the MaXXI was the first new public museum in Italy dedicated to contemporary art and architecture. Its Roman numeral-heavy name combines a nod to its cultural heritage whilst grandiously staking a claim to that of the future century. Yet given this moniker promising a certain size, the building is oddly small in scale as though it shrank in the wash (perhaps a trace of that most powerful of parametric parameters: budget cuts).

The intense sense of movement in the early studies for the building’s form, riffing off the sinews of the surrounding city, recaptured much of the energy of Zaha’s early work. Its flowing forms seeming to channel powerful urban ley lines in this, one of the ancient ur-capitals of the world. But the energy of the actual building appears to have got lost in completion, the exterior of its final form feels massively, concretely still and sculptural, all frozen curves and gestures. So although the glazed eye of the topmost gallery, rearing and curving back over itself, is reminiscent of a snake peering back over its tail – it’s more of the dead and stuffed variety.Photos previous page and this page: Flickr/Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

-

Inside the building however, the flow really does get going in the extraordinary, sometimes beautiful, interior, starting with an Escher-esque stair, that leads on to long, fluid gallery spaces.

But it is a flow to nowhere as though a literal manifestation of Marc Augé’s theory of “non-places”: spaces of passage and travel like airports – with no satisfying punctuating moments of stasis. Underlining this is a manifest lack of interest in detailing and materiality, in the hapticity of touch, and indeed of any senses other than the visual, as though visitors are just non-stick ocular vectors moving through the space.

It’s an old cliché, but these are architect-designed galleries that are pretty incompatible to showing or looking at art. Much of what is on view here appears a bit off-kilter and awkward in spaces that are more akin to expanded corridors. Like Libeskind’s Jewish Museum in Berlin, one suspects that the MaXXI would look better empty.

But five years on from its inauguration, despte being threatened with closure two years ago in the budgetary backwash from the Eurozone crisis, the MaXXI seems to be bedding down at last thanks to the appointment of Chinese curator Hou Hanru as its artistic director in 2013. He is someone with a requisite global perspective but also a strong enough curatorial vision to compete with the idiosyncracies and tropes of a building which he acknowledges but embraces:

“This building is based on a very clear vision of neo-liberal capitalism ... it could easily be an airport building, or a shopping mall.” he has said: “Of course this is a very strange building but if there’s no challenge then it’s not interesting.”

So rather than expecting this museum to be a neutral storehouse for art, perhaps it is best to see it as an artefact of a particular time. Like the factories and industrial spaces of the early twentieth century that came not only to be used for but to engender art later on, the MaXXI, with its capricious gallery spaces, might yet fulfill its role as a locus for the art of the twenty-first. I (rgw)![]()

Photos: © Roland Halbe

-

Pet Shop Girl

Neil Tennant, one half of the pop duo the Pet Shop Boys, is a self-confessed architecture fan. Back in 1998 they asked the, as yet unbuilt, architect Zaha Hadid to design the stage set for their Nightlife World Tour 1999-2000. Here he describes for uncube how the commission came about:

“Basically we decided to collaborate with Zaha because a book about her work had just been published and most of the projects in it were unrealised. We felt that she had an amazing dynamic sensibility that would work great for a stage set. We also found the idea of involving someone who was completely outside the music, or even the theatre, scene really interesting. I was impressed by what an incredibly strong woman she is, to be able to stand her ground in this very male-dominated profession. We were really proud that our opening show in Birmingham for the tour featured one of her very first ever built projects in the UK.” I (sl)

Photo courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects

![]()

Pet Shop Boys performing “It‘s a Sin” live during their world tour in 1999/2000. Video: excerpt from the documentary “Montage – The Nightlife Tour” (Parlophone/EMI, 2001).

-

Brendan Cormier is the lead curator of the Shekou project at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London where he is working to establish a new V&A gallery in Shenzhen, China. Prior to this he was the managing editor of Volume as well as a contributing writer to the several publications including Mark, Domus, Azure, and Canadian Architect on architectural and urban issues. In 2009 he co-founded the research and design studio Department of Unusual Certainties in Toronto, where he designed several exhibition installations that explored urban issues. In 2011 he was named innovator-in-residence at the Design Exchange, Canada's national design museum.

-

There’s a long tradition of architects flirting with the field of design. Early modernists began their careers crafting polemical furniture, while others designed Gesamtkunstwerk-like interiors, from the curtains down to the tableware. Some traces of this tradition still persist, but few have jumped so ambitiously into the world of product design as Zaha Hadid. Her practice has gone so far as setting up a separate company, Zaha Hadid Design (ZHD) to oversee the production of what has become a vast range of objects.

At a glance, these works look typically “Zaha”, replete with amorphous blobs, flowing shapes and shiny surfaces. But while the office has worked hard to establish a theoretical foundation to underpin its architecture, the driving ideas behind ZHD are more elusive. The company insists the designs are not “buildings in miniature”, but they offer few other clues as to how to interpret the works. After exhausting the visual references of H.R. Giger, science fiction films, and the countless organic shapes her work can be compared to, there is not much more a critic can do.

In this sense, a critique of ZHD objects seems self-defeating. More worthwhile, perhaps, is to ask why they are successful. What does the success of ZHD tell us about the world we live in? Some notes then on the world through five ZHD objects. -

![]()

Design for the .01%

Unique Circle Yachts for Blohm+Voss

![]()

As we enter a new gilded age of income inequality, the superyacht has emerged as the perfect symbol of excess. Celebrity designers have recently entered the fray, lending the super-valuable boat even more distinction with their designer touch. Norman Foster, Philippe Starck, and Renzo Piano have all designed yachts, but it is ZHA’s Unique Circle Yachts prototype for Blohm+Voss (2013-tbc) that is the most exuberant. Combining metaphors of fluid dynamics and organic structural systems, the boat is wrapped in a sinewy exoskeleton that seemingly explodes from the water. All available for a wildly unattainable price.

The rarefied eccentricity of ZHD design plays well to an ultra-affluent crowd looking for exclusivity and flash. The early modernists dreamed of good design for all. ZHD, like an increasing number of contemporary designers, dream of good design for those with cash.All images and photos courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects

-

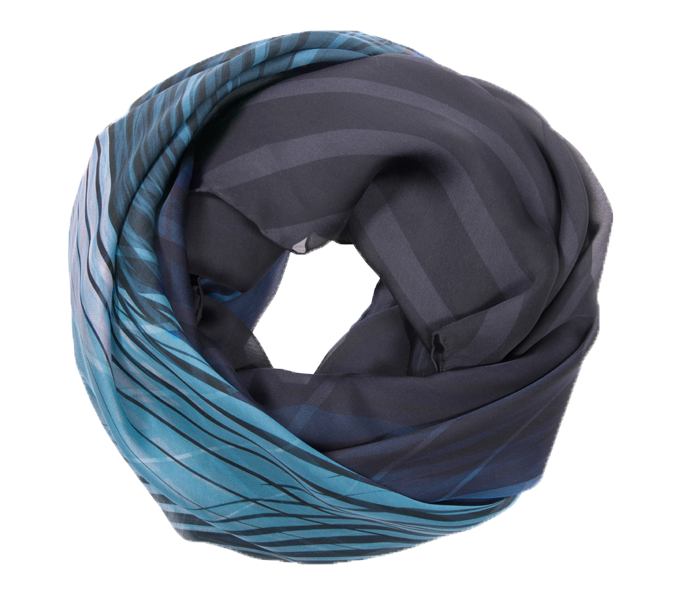

Design Complicity

Silk Scarf for Dongdaemun Design Plaza

![]()

Zaha Hadid has often come under fire for working with controversial clients and projects. This scarf was designed in 2014 to commemorate another ZHA project, the Dongdaemun Design Plaza in Seoul. The project was heavily criticised because it allegedly necessitated the demolition of an important historic area of the city, whilst consuming large amounts of tax-payers’ money.

Patrik Schumacher has often said that ZHA’s parametric style is a metaphor for our new era of networked complexity. However “networked complicity” might be more apt: a complicity all designers face where the desire for work – and fees – comes into conflict with the moral conundrum of where that money came from.![]()

-

The Value of a Brand

Prime Oriental Scented Candle

![]()

A signature sells. Most celebrity architects have ridden a wave of success by building an identifiable brand style: think Gehry’s billowing swoops or Libeskind’s jagged crystals. Hadid’s brand is among the strongest, and it’s a testament to this strength that even when transcending different mediums, the signature still holds. Hans Hollein famously claimed that everything is architecture and ZHD do a pretty good job here at showing how even a candle can be given an architectural aura. The Prime Oriental Scented (2014) candle looks like a model of a tower for an oil tycoon. But not everyone is an oil tycoon, and any good brand strategy involves a diversification of price points. Retailing for 69 GBP, the candle represents a relative democratisation of the ZHD brand. Other luxury brands offer perfume as their gateway drug to their other products - here, the scent of the candle lets you dream of higher-up-the food-chain Hadid: shoes, a chair, even your very own building.

![]()

-

Design as Art

Aqua Table

![]()

The distinction between art and design has become increasingly blurred. A good example is the Aqua Table, conceived in 2005 as an offshoot of Hadid’s design for the London Olympic Aquatics Centre. Its polyurethane resin prototype broke records in 2005 when it was auctioned in New York for 296,000 US dollars, the most money paid for an object by a living designer at the time. This record, since shattered by the 2.4 million GBP paid for a Marc Newson’s Lockheed Lounge Chair in 2015, is indicative of an increasing trend where design objects are treated like art, boosting their value and the fame of their maker. Several practices, ZHD included, use art world strategies to position their works closer to the aura of an artwork, making limited editions, shown in gallery settings. Indeed ZHD established its own private gallery in Clerkenwell two years ago, as a permanent space to display its works.

![]()

-

Cross-Disciplinary Everything

United Nude Shoe Nova

![]()

We live in a world where everyone’s a DJ; that’s to say, whether it be through new digital tools, or a new cultural interest for cross-disciplinary exchange, more people are trying their hand at different mediums, and often with surprisingly good results. We’ve discovered that filmmaker Wes Anderson is a pretty good interior designer, and that artist Ai Weiwei is not a bad architect. Sometimes these collaborations can have pretty radical results, pushing a medium out of a formulaic rut. In the case of shoes, United Nude, have drastically changed our image of what footwear can be, precisely by choosing a strategy of cross-disciplinary fertilisation. For her NOVA shoe (2013), Hadid introduces the architectural concept of a cantilever, a trope in architecture but a radical concept in footwear. The result, combined with characteristic Zaha flourishes, is something incredibly fresh. I

![]()

-

![]()

![]()

Wonderfully

DishonestImpressions of the

Heydar Aliyev Center in Bakuby Vladimir Belogolovsky

Admirers and critics of Zaha Hadid’s work alike cannot deny her enormous influence on where architecture is headed. Her practice’s theories are tested at design schools all over the world and their work has pushed the building industry towards technical virtuosity and sophistication, says architecture critic Vladimir Belogolovsky. Here he gets under the skin of his favourite Zaha Hadid Associates building and finds himself in a love/hate dilemma.

-

![]()

The Hadid building that has impressed me most is Heydar Aliyev Cultural Center in Baku, Azerbaijan. I had the privilege of visiting the place, named after the president (father of the current president Ilham Aliyev), shortly before its official opening in 2012. This sensational structure is not easy to describe. It is also highly complex. Even the Center’s curator told me he constantly gets lost inside and finds himself discovering new ways of navigating it. Is that a good thing? Sure it is; as Renzo Piano once noted, “A museum is a place where one should lose one’s head”.

Instead of simply describing the building, I will use it as a vehicle to discuss various issues, and to talk about, to borrow Will Alsop’s phrase, “not what architecture should be, but what it could be”.

The Baku project is not unique. It explores the notion that a building is not merely an object, but an integral part of the surrounding environment, be it landscape or city. Hadid has done this time and again, and many other architects – from Frederick Kiesler to Oscar Niemeyer to UNStudio – have achieved this with no less passion and originality. Still the project in Baku stands out, as both its scale and complete integration into the land around it are breathtaking.

And the building proves another point – that we can’t dissect architecture into elements, as attempted by Rem Koolhaas at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale. Architecture is not merely the sum of its parts. The reason I like the Baku project is precisely because from the exterior one cannot recognise any of the familiar elements that make it look like a building: doors, windows, steps, handrails, facades, roofs – none of them – which means one cannot possibly tell what’s inside.

Heydar Aliyev Centre, 2007-12, Baku, Azerbaijan. (Photos this page and previous page: Hufton + Crow)

-

![]()

Photos: Vladimir Belogolovsky

-

Vladimir Belogolovsky (b. 1970, Odessa, Ukraine) is the founder of New York-based non-profit Intercontinental Curatorial Project with a focus on curating architectural exhibitions worldwide. He is the American correspondent for architectural journal SPEECH (Berlin) and the author of six books, including Conversations with Architects in the Age of Celebrity (DOM, 2015) and Soviet Modernism: 1955-1985 (TATLIN, 2010).

curatorialproject.com

![]()

But much as I like the building’s shell, I dislike what is within. The inside and outside of this building are completely independent projects. Once inside you start to see what is so masterfully avoided on the outside: steps, handrails, columns… In short, the familiar and predictable. You might ask, how can these fundamental elements be avoided? Well, if I knew, I would be doing my own architecture, not merely talking about it. But some of Hadid’s interiors are more successful than others in this respect. In the MAXXI in Rome, for example, nothing interrupts the overall flow of architecture that reads as a single whole. Perhaps the vast scale of the Baku building made it more challenging.

But let’s not dwell on the things that don’t work and go back outdoors to where the building is a true spectacle and a pleasure not just to the eye, but to the body as well. It constantly invites you to come into contact with it and even climb on its back. One might even imagine running over it all the way to the top. But step closer and you will realise quite quickly how challenging this would be. The building is much too steep. It kicks you back, as if it were a living creature.

But here is another question, one that the modernists used to ponder: is this building “honest”? Well, the answer is quite obviously “no”. It is not honest in the modernist sense of the word since it clearly conceals the way it is constructed. Everything within physical reach is made of “liquid” stone. Once out of reach, this material shamelessly changes to metal panels. You can’t tell though. Visually, there is no break between one material and another. The same happens on the inside – concrete and plywood flooring transition seamlessly into gypsum board walls and ceiling. Everything is a surface.

Is a dishonest building a good thing? Well, this is where I would say that architecture is not about generalisations. The very idea that an object can be “honest” is meaningless. Every case deserves its own examination. Take Eero Saarinen’s 1956 Tulip Chair for example. This futuristic design is a classic yet it is far from honest. Its base is made of metal, whereas the seat is plastic, yet one flawlessly segues into the other to make a beautiful and smooth form without acknowledging the two inherently different materials. What does this say to you? Don’t fall for clichés; follow your eye.![]()

-

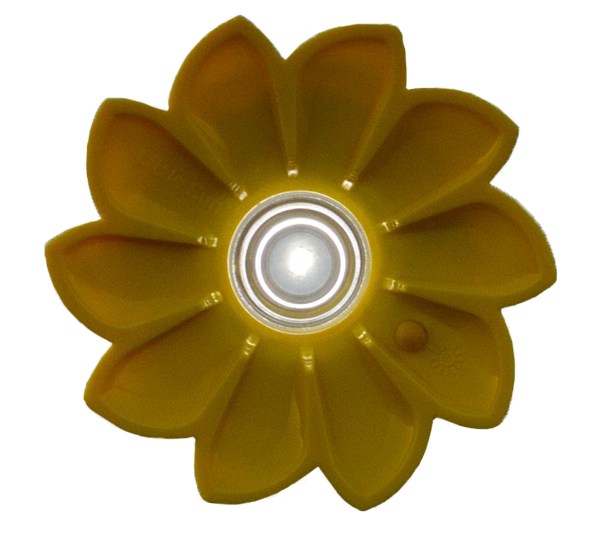

The world just got littler...

The world just got littler...

To hold one in your hand is to hold a tiny power pack, but its energy comes from the greatest source of energy we know. The sun charges it and it charges your life at the same time.

Maybe you’re a Zimbabwean child that needs a light to study by at night. Or you might be headed to the Roskilde Festival and you need a light for your tent. Maybe you’re going hiking with your friends and you want something better than a battery-powered torch. Or you work in a Himalayan village and you need a hand-held light to guide your way back home through the mountains. You could be a design-nerd and you want to own a little light designed by Olafur Eliasson.

Or you’re a Sudanese mother and you want to prepare your family’s meals under a safe and healthy source of light. Or maybe you have a young family in Berlin and you want a colourful way to teach them about sustainability.

Whoever we are, wherever we go, there is more that connects us than divides us. And one of the most important things that holds us together is that we all need light in our lives. Of course the greatest light we have is the one we all share: the sun.

Sometimes it’s nice to feel that the big wide world just got a bit littler.

Welcome to our little world:

www.littlesun.com

![]()

![]()

-

In the Photo Booth with

Patrik schumacher

Architect and mathematician Patrik Schumacher brought algorithmic computer-generated design to the hand-drawn world of Zaha Hadid’s mathematically inspired works. He joined her practice as a student in 1988 and became a partner in 2002. He is the digital right hand of the practice that has helped shape many of the signature Zaha Hadid Architects’ buildings now known worldwide.Interview by Sophie Lovell

Photos by Davide Giordano, Zaha Hadid Architects

![]()

-

You studied philosophy and mathematics before architecture. Was it the mathematics that initially drew you to the work of Zaha Hadid?

What drew me to Zaha Hadid was the dynamism, complexity and elegance of her geometry, and indeed the mathematical precision of her work.

Can you remember your first meeting with Zaha? What were your impressions?

I discovered and studied her work in 1985 as a student in Stuttgart, and first encountered Zaha Hadid in person in 1988 at a Deconstructivism symposium at London’s Tate Gallery. I was struck by her no-nonsense, straightforward, honest presentation of her ideas and work, compared with other rather pompous and self-conscious presentations. Zaha was relaxed and confident, I guess well aware that her work was much more compelling than that of the other architects. I joined her studio that same year, whilst I was still a student.

-

Would I be right in thinking that you brought parametrics to the practice?

Yes, that’s correct, but Zaha’s work already exhibited all of the essential features of parametricism – dynamic curvature, complexity of integrative layering etc. – albeit created through elaborate hand drafting and painting. In my book Digital Hadid I trace our development from an analogue to a digital methodology and how Zaha’s work acted an inspiration and challenge for developing digital design techniques.

-

How did your working relationship develop into a partnership? How would you say your respective qualities interact? What do each of you bring to the work?

That’s a difficult question, perhaps best answered by a third party observer. When I started working with her it was a very small studio: only five people. Soon after, Zaha’s primary design collaborator resigned, so I was suddenly challenged to step up and take a bigger role. My first project was the Vitra Fire station, which became Zaha’s first significant built work. We were still working by hand then and I worked out the spatially curved geometry via orthographic projection. At the same time we were working on many competitions, for which we started introducing computers as design and visualisation aids, first as 3D sketching tools and then later as planning and drafting tools. We also started teaching together, at Columbia in 1993 and Harvard in 1994. It’s there we expanded our experimentation with computational techniques. This finally took off when I started teaching at the AA, and founded the Design Research Laboratory.

It’s very hard to separate our roles as we work closely together and discuss everything. But, if I had to, I would say Zaha has always been the engine and energy behind the drive to originality and perfection, while my role has been to discipline and channel this creative power. Now, there are many colleagues equally indispensable to the overall creative force and success of the firm. -

Patrik Schumacher, is partner at Zaha Hadid Architects and founding director at the AA Design Research Lab. He joined Zaha Hadid in 1988.

Patrik Schumacher studied philosophy and architecture in Bonn, London and Stuttgart, where he received his Diploma in architecture in 1990. In 1999 he completed his PHD at the Institute for Cultural Science, Klagenfurt University.

Schumacher has been teaching at various architectural schools in Britain, Continental Europe and the USA since 1992 and a co-director of the Design Research Laboratory at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London since 1996. Currently he is a tenured Professor at Innsbruck University and his contribution to the discourse of contemporary architecture is also evident in his published works.

patrikschumacher.com

Why do you think some people still have trouble accepting your work?

Our work is often misunderstood as self-indulgent, artistic exuberance, aiming for the spectacle of iconic architecture. That’s not how we see it. What critics don’t understand is that an architecture that’s rigorously developed on the basis of radically new, innovative principles becomes conspicuous by default rather than intention, and that urban and architectural complexity are not ends in themselves but are called for by the new societal complexity of contemporary post-fordist network society.

Looking back in the future, what do you think you would say the legacy of the Zaha Hadid Architects has been?

Zaha Hadid Architects is now a firm of about 350 architects taking on all building types and operating across all continents. Yet we remain absolutely consistent in our commitment to parametricism as the only truly new, viable and indeed superior way forward for architecture, urbanism and all the other design disciplines that give our man-made world its spatial order and visual, tactile shape. My hope is that our work spurs on the movement of parametricism to complete the move from avant-garde to mainstream and to establish it as truly an epochal style of global best practice, one that can impact and transform the built environment in the way modernism did in the 20th century. So I hope that a different, much richer, organic and nature-like built environment will be our legacy, a built environment that is both more complex and more legible and far less monotonous and disorienting than many placeless and ugly cityscapes today. I guess this is a lot to hope for.

-

![]()

![]()

Mending Space

Admiring the stitching skills of Zaha Hadid

By Andreas Ruby

![]()

Architecture critic and publisher Andreas Ruby’s favourite Zaha Hadid project is the Hoenheim-Nord Terminus and Car Park built 1998-2001 in Strasbourg, France, despite – or precisely because – of it being probably the most unusual and unrepresentative project in her entire oeuvre.

-

The work of Zaha Hadid is known and celebrated today for its dazzling capacity to create spectacular buildings, that irresistibly attract global attention with their audacity of form. While I can appreciate her approach for its artistic craft and power, it seems to me that over the years it has led to increasingly predictable results: bold sculptural statements that fetishise their own presence into a spectacle, while rarely giving something back to their surroundings.

The Hoenheim-Nord Terminus is very different in that regard, because it generously invests its formal power in mending a suburban space that obviously no planner had cared to think about much. I believe it is able to do so because it is not a building so much as a cross-breeding of traffic infrastructure and landscape architecture. Located at the outskirts of Strasbourg, it provides a traffic hub that links individual car traffic, train, tram and bus lines. Thus commuters from the region can get to the edge of the city by car and then proceed to its centre by public transport. Like stitching two pieces of fabric that once were one, the Terminus brings periphery and city closer together again and I like the fact that you can experience this act of spatial compression with your senses when you are on the site.

Aside from the concrete roof of the tram station that folds up from the ground of the car park, the project consists for the most part of flat ground. But this ground is worked in a way that empowers the void in a manner that cannot be photographed. You can also not easily see it, because the main articulation of this void is a swoosh-like figure that sits as an inlay of light concrete in the darker asphalt ground of the car park. It only really shows from a bird’s eye view, like some vivid giant brush stroke.![]()

![]()

Previous page: Hoenheim-Nord Terminus and Car Park, 1998-2001, Strasbourg, France. (Photo: Hélène Binet); this page: aerial view. (Photo: Roger Rothan, Airdiasol)

-

Andreas Ruby is an architecture critic, curator, moderator, teacher and publisher. He has taught architectural theory and design at a number of institutions worldwide including: Cornell University, École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture Paris Malaquais, the Metropolis Program Barcelona and Umea School of Architecture. Aside from his contributions to selected international architecture magazines, he has published nearly 20 books on contemporary architecture. In 2008 he co-founded the architecture publishing house Ruby Press.

ruby-press.com

(Photo © Patricia Parinejad)

»Zaha Hadid would have been a killer land artist. I would love to see the work she could have produced had she opted for that career.«

Literally walking over the image in the ground, we only catch bits and pieces of it: the curvilinear pattern of white markings on the ground delineating parking spots – some doubling as lighting, or the forest of inclined lampposts that rises above the field of parking, forming a filter through which you look at the surroundings.

Both conditions make parking your car here become an experience in itself. The ground markings and the lampposts perform a ballet of lines that is set in a virtual motion as soon as you move across the car park by foot or car. It is a kinetic installation at the scale of territory itself, fantastically fusing the optical illusions of movement like in Bridget Riley’s paintings, the territorial acupuncture of Walter de Maria’s Lightning Field, the physical treatment of ground in Michael Heizer’s Double Negative or the diagrammatic optics of the asphalt ground in Ed Ruscha’s aerial photographs of L.A. parking lots.

Hoenheim-Nord Terminus makes you realise that Zaha Hadid would have been a killer land artist. I would love to see the work she could have produced had she opted for that career. That’s what makes this project so precious and unique to me. It is not only a real space, but also a walkable map of potentialities that you can chose to act out in your mind. Which is why you can go back there again and again and always discover something new. IPhoto: Hélène Binet

-

FURTHER READING

Blog Interview08 Sep 2015

What am I a Citizen of?

Liam Young advocates the utter dissolution of the term architect

Blog Interview26 May 2015

Into the Cyber-Physical

An Interview with Achim Menges

Blog Interview01 Oct 2015

Shooting Zaha

A photo essay and interview with photographer Hélène Binet

Blog Building of the Week21 Jan 2014

Pretty, Vacant

Zaha’s new Beijing Bubbles

Magazine Interview16

The Lightest Touch

Architect Greg Lynn believes the good outweighs the bad when it comes to carbon composites

Blog Venice 201427 Jun 2014

The Dark Side Club

What architects really talk about when they are alone.

Search our archive! -

DEATH

Issue No. 38:

November 2nd 2015

Photo: Daniele Libero Campi Martucci

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema