-

Focus on Frei Otto by his colleagues and peers

By Stephan Becker

Great architects are not necessarily great teachers, nor great advocates for their ideas. So what was so different about Frei Otto that his influence can be traced in the designs of the world’s most renowned architects? For him, designing wasn’t about fancy uniqueness or a sensational display of his skills, but about finding an ideal solution to a fundamental, often existential problem. He was like a researcher without the need or desire to do follow all his research through to conclusion, but with the satisfaction of seeing his seminal ideas spreading through other’s work. His dedication and work drew an illustrious collection of admirers such as Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid and Renzo Piano. Frei Otto was someone to be inspired by, not to compete with. This explains the relationship between his comparably small built oeuvre and the great number of projects by others that pick up on his ideas. He was equally influential in spatial, technological and conceptual areas, as some of his famous friends tell us here in their own words.

-

“Like Luis Kahn asked the brick, Frei Otto kept asking the air what it wanted to become. He kept thinking about how to envelop ‘air’ with the minimum of ‘material’ and power. His achievements, rather than just being his ‘works’, have become the grammar of structural design, unnoticed by many, and we are only now realising that we unconsciously base our designs on his grammar.”

At first sight, in relation to Frei Otto’s projects, some of Shigeru Ban’s designs seem to be the work of an ardent fan. But a closer look reveals his own achievement: not only the adaption of Otto’s original ideas for new materials and construction techniques, but also the marriage of different spatial paradigms. The tent and the box, together forming a new typology that allows for different uses and programmes.

Shigeru Ban. (Photo: Flickr/Valerij Ledenev, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Centre Pompidou-Metz, 2010, Paris, France. (Photo: Flickr/Martial Geoffroy, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

»Like Luis Kahn asked the brick, Frei Otto kept asking the air what it wanted to become. His achievements have become the grammar of structural design.«

Shigeru Ban

-

Even though Renzo Piano is twelve years Frei Otto’s junior, their work has to be seen more as a parallel and intertwined development than a simple following. Interestingly, their shared interest in lightness has usually led Piano to very different solutions. This is especially apparent with his projects sited in historic surroundings, where he combines constructonal efficiency with a strong sculptural presence.

Renzo Piano. (Photo © Ed Alcock)

»Frei Otto has been one of the most seminal people on my route to architecture. Exploring the movement of forces within the structure to make it visible. Celebrating lightness. And fighting against gravity.«

Renzo Piano

Biosphere, 2001, Genoa Porto Antico, Italy. (Photo: Flickr/Basilicataintir, CC BY-NC 2.0)

-

“The fluidity of Frei Otto’s work is as uplifting as it was profoundly inventive – a persuasive manifesto of nature’s logic and unity, demonstrating how architectural design and engineering can emulate nature’s morphogenesis. The more our own design research evolves, the more we learn to appreciate his pioneering works. We first met in Germany early in my career and he became a dear friend.”

Particularly in her early years, the decisively modern architecture of Frei Otto didn’t seem the most likely inspiration for Zaha Hadid – who was a major proponent of deconstructivism back then. On the other hand, her interest in Otto’s work is not just limited to technological aspects, but to the spatial effects it created. A tent, for her, is not just an efficient way to span large areas, but an actual piece of architecture to be experienced, a piece of architecture epitomising the dynamics of life. This wasn’t always one of Otto’s main concerns, perhaps, but it quite often accompanied the public perception of his projects. With very different concepts and materials, Hadid takes this approach to an entirely new level.

Zaha Hadid. (Photo © Brigitte Lacombe, courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects)

» The fluidity of Frei Otto’s work is as uplifting as it was profoundly inventive – a persuasive manifesto of nature’s logic and unity, demonstrating how architectural design and engineering can emulate nature’s morphogenesis. «

Zaha Hadid

London Aquatics Centre, 2011, UK. (Photo © Hufton + Crow, courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects)

-

“Frei Otto showed us that architecture need not be burdened by the weight of its own traditions, but could instead be free to express itself through simple but innovative sculptural forms – his was an architecture inspired by lightness. This sense of weightlessness, and of an architecture unbound by convention, was carried over into Frei’s working relationships. For me, he reinforced the point that architecture is a fundamentally collaborative exercise. His structures altered the nature of architectural form in the twentieth century and his environmentalism, intelligence and foresight have established the defining architectural mentality for the twenty-first.”

It is very easy to find formal aspects in Norman Foster’s work that bear reference to Frei Otto’s projects. But more importantly, Otto’s unique combination of technology and nature showed Foster how to move on with modern architecture amidst all the post-modern dissidence. It is not in any particular design but in Foster’s fundamental approach to practice, where Otto’s thinking becomes most apparent.Norman Foster. (Photo: Flickr/Fabian Mohr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Buenos Aires Ciudad Casa de Gobierno, 2010, Argentina. (Photo © Foster + Partners)

»His structures altered the nature of architectural form in the twentieth century and his environmentalism, intelligence and foresight have established the defining architectural mentality for the twenty-first.«

Norman Foster

-

Wanting to build often means having to compromise, and that’s perhaps one of the reasons why Frei Otto so decidedly focused on research and collaboration. It allowed him to work only on pioneering projects, a rare privilege he shared with the architect and engineer Cecil Balmond (born 1943). Despite teaming up with some of the world’s most renowned practitioners, for Balmond, as it was for Otto, the true field for experimentation is his individual work. In his studio or at the university, Balmond mirrors Otto’s fundamental curiosity across every aspect of practice.

Cecil Balmond. (Photo: Olivier Hess)

»When I first saw Frei’s work I felt the rush of discovery, the images opened up and revealed minimum surface, optimisation and grace of form – he was a one-off.«

Cecil Balmond

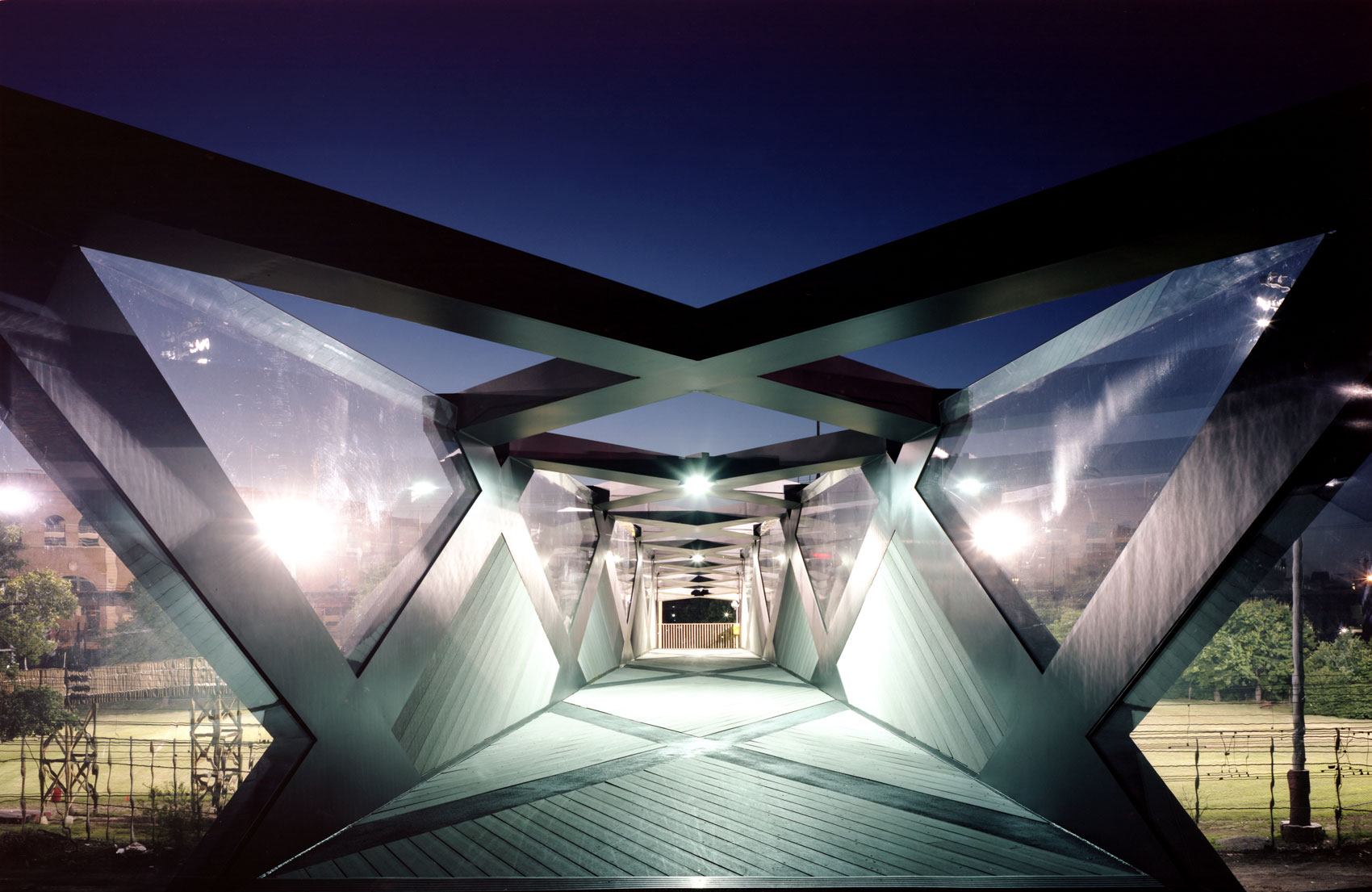

Weave Bridge, 2009, University of Pennsylvania, USA. (Photo © Alex Fradkin)

-

Membrane structures have a very particular aesthetic, simply because they follow the fundamental laws of physics. For Michael Hopkins, on the other hand, this isn’t something to just accept. Showing a similar spirit to Frei Otto’s lifelong search for new approaches, his complex systems redefine what can be done with flexible materials. Not just tent-like structures, but any architectural form needed for a specific use.

Michael Hopkins. (Photo © Tom Miller, courtesy Hopkins Architects)

Schlumberger Cambridge Research Centre, 1992, UK. (Photo © Dave Bower)

»For me, Frei Otto was the grandfather of all our membrane structures. We discovered that membranes would not only enclose space and transfer light, but would also transfer load and stress. We owe him a great debt.«

Michael Hopkins

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»I hate vacations. If you can build buildings, why sit on the beach?«

Philip Johnson

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents