-

by Wilfried Kuehn and Marlies WirthPhoto courtesy MAK

-

Wilfried Kuehn (of Kuehn Malvezzi Architects) and Marlies Wirth (curator MAK), joint curators of the Hollein retrospective currently showing at the MAK museum in Vienna, explain what made this extraordinary all-rounder so significant and why Hans Hollein really was all about “architecture and beyond”.

Hans Hollein (1934–2014) was a Pritzker Prize-winning architect, designer, artist, curator, exhibition organiser, theorist, educator, city planner, media visionary, and cultural anthropologist. As a designer in the most comprehensive sense, Hollein gave the term “architecture” a new dimension and his still relevant analysis of “a world shaped by man”, turned a fundamental question into a visionary statement: “What is design?” Here, we try to pinpoint his main areas of influence and innovation through key areas of his practice and specific projects from his long and rich career. The accompanying photographs are a selection from new images of Hans Hollein’s buildings especially commissioned for the Hollein exhibition from the artist-photographers Aglaia Konrad and Armin Linke.

-

The Building Unfurls Itself

Hollein’s interest in museums was an interest in the exhibiting process. His aim was to design displays of museum collections as experimental, shifting arrangements in space rather than canonical art historical presentations. The Museum Abteiberg (1978-82) plays a pivotal role in Hollein’s oeuvre. In its heterogeneity the building is a sequence of spaces, each with its own unique character. They do not form some ideal whole but function more like a montage of contrasts. The museum architecture is neither a typologically idealised space nor a generic real space; it is a hybrid. Hollein created the conditions for artistic production and spatial installation but also for exhibition formats that expand performatively. Due to intersections designed around his “clover leaf” pattern floorplan, the building unfurls itself in the heterogenous paths of the visitors as a series of situations, alternating with, and following on urprisingly from, one another: suddenly coming into view and disappearing again like variations in a landscape.

The room progression concept that was developed for the Museum Abteiburg transforms the open corners of the rooms into pivotal points that activate the visitors in the exhibition space. Their gazes and movements interconnect the rooms and the works installed within them, replacing the traditional linearity and chronology of the exhibition situation with one of simultaneity. Hollein’s typological innovation was an expression of the shift that had taken place in the museum in the wake of the buildings of late Modernism, such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe‘s Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 1967. Like Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’ Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, also designed in the 1970s, the Museum Abteiberg was a radical new exhibition space integrated into the everyday fabric of the city rather than sitting elevated above it like a temple. Hollein designed the museum from the inside out, as a space for producing and experiencing the exhibiting process. It was conceived as an urban space in the urban context that continues and expands around it like an artificial landscape.Museum Abteiberg Mönchengladbach, 1972-1982. (Photo: Aglaia Konrad)

-

Museum Abteiberg Mönchengladbach, 1972-1982. (All photos: Aglaia Konrad)

-

The Kinaesthetic Experience of Space

The exhibiting process and the visitors’ kinaesthetic experience of space stand at the heart of Hollein’s work. The Museum Abteiberg is an “accessible house”, the first Hollein built after working on the idea as a student. Back in 1958, when visiting the US for the first time, Hollein showed particular interest in the Native American pueblos in the New Mexico region, basic adobe dwellings and settlements as distinctive as they are complex. The term pueblo stands for the individual and the whole: the house is the city, the architecture is the accessible landscape; the private is related to the public, the ritualistic to the quotidian. In his designs for the central Sparkasse bank in Vienna’s Floridsdorf district and for an accessible department store in St. Louis, Hollein transformed the step-like constructions of traditional adobe buildings into models for accessible houses, which generated public space on their terraced roofs. It was with the Museum Abteiberg that Hollein was first able to realise his idea of a building as landscape and public space rolled into one; it gouges itself into the hillside and offers its own roof as urban space.

In the Volksschule Köhlergasse, realised in Vienna in 1990, Hollein applied his accessibility principles to a school building. Every classroom was given its specific shape using special ceiling formations and he added a series of semi-public spaces to function like city squares. These spaces, where interior and exterior meet, generate a city within a city that is inhabited by children. During breaks between lessons, they can enter this outside space that is also public space, and learn to occupy it. By upgrading these interstitial spaces Hollein brings the urban environment into the school and with it, the opportunity for the children to subjectively appropriate their school environment as a constellation of situations and spaces.Elementary School VS Köhlergasse, Vienna, 1979-1990. (Photo: Aglaia Konrad)

-

Aglaia Konrad was born in 1960, Salzbourg, and lives and works in Brussels. She is an artist who has developed a distinct manner of photography that documents the rapidly advancing process of global urbanisation. Her archive, which encompasses several thousand images of urban infrastructures and housing architectures, offers an unlimited repository that sheds a unique light on the relationship between society and space.

Elementary School VS Köhlergasse, Vienna, 1979-1990. (All photos: Aglaia Konrad)

-

Everything is Architecture

Hollein addressed the influence of the environment in the broadest sense of the word in his masters thesis at Berkley in 1960, in his 1963 exhibition Architecture with Walter Pichler in the Galerie St. Stephan in Vienna, and again in his 1976 manifesto Everything is Architecture in Bau, the magazine he published. During this period he created a series of projects that tested the physical limits of spatial awareness and how potentially to overcome them: Communication Interchange (1963), as a city model of total interconnectedness;

Minimal Environment (1965) in the form of a telephone cell as total habitat; Non-Physical Environment (1967) in the form of a pill; Spray zur Umweltveränderung [Spray for Changing the Environment] (1968) and his Vorschlag für die Erweiterung der Universität Wien [Proposal for Extending the University of Vienna] (1966) in the form of an informational rather than physical network that was a more radical alternative to Cedric Price’s Potteries Thinkbelt university concept from the same year.

The Indissoluble Relationship

The concept of “mediality” – a media-saturated reality – is central to Hollein’s work and underpins each of his projects. His starting point is the indissoluble relationship of permanent mutual production into which man and environment are locked. In this process, as Hollein posited in his curatorial-architectural plans for his MANtransFORMS 1976 exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt Museum, New York, design constitutes the prototypical human activity of environmental production. At the centre stands the Body, in the force field of Space and Time Experienced, of Behaviour, Politics, Face and Tools.

Media Lines Olympic Village, Munich. (Photo © Armin Linke, 2013)

-

In between are conjoining themes like living together, eating, clothing, tools, ritual, death, drugs, etc. Instead of valuable artefacts he presented everyday objects and their production through human activity. Using the topos of “A Piece of Cloth” Hollein showed variations of a simple object right the way through to the development of complex human achievements such as housing, protection and ritual, flags, communication media, tools, energy generation and mobility. In front of the entrance to the Cooper Hewitt National Museum, Hollein installed a tree trunk whose base was still covered in bark and whose top had been planed to a timber beam. Half-nature, half-artefact, it stood for Hollein’s entire exhibition project in which design was presented as the transformation process of man and object as well as the potential for social processes.

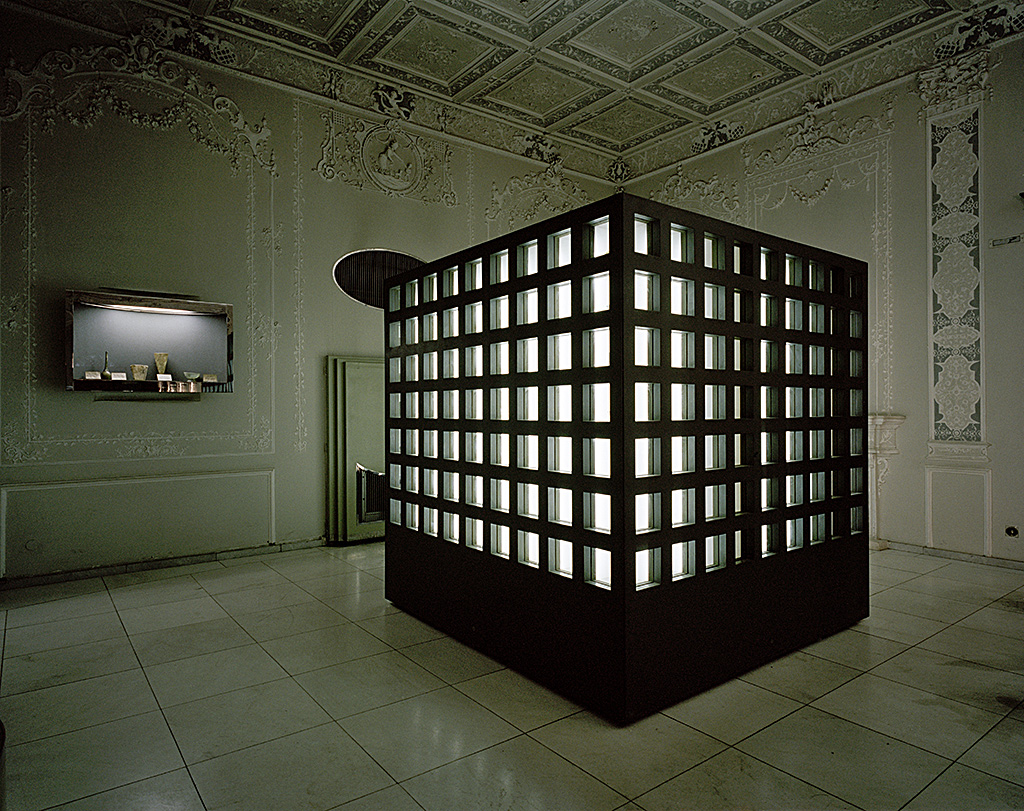

The Media Lines, realised in Munich in 1972, were the prototype for Hollein’s media environment-as-architecture. They formed an environmental conditioning and communication system for the Olympic Village, which could also be read as public art, architecture and guidance system. In his projects of the 1970s Hollein transformed the pipes of the Media Lines into a museum display system, most notably in the 1978 Tehran Museum of Glass and Ceramics.

The museum in Tehran reads like a catalogue of display solutions that appear as strange vitrines implanted into the historical building. Like minimal environments mounted into the fabric of the museum, the vitrines are the communicative end point of their own network and occupy selected spaces around the building, from the exterior wall to the parquet floor, functioning as a museum in a museum.Media Lines Olympic Village, Munich. (Photo © Armin Linke, 2013)

-

Armin Linke was born in 1966 and lives in Milan and Berlin. He is an artist working with film and photography, combining different mediums to blur the border between fiction and reality. He is working on an ongoing archive concerning human activity, and natural and manmade landscapes. He is professor at the HfG Karlsruhe, guest professor at the IUAV Arts and Design University in Venice, and Research Affiliate at the MIT Visual Arts Program, Cambridge.

Media Lines Olympic Village, Munich. (Photo: Armin Linke)

Museum of Glass and Ceramics, Tehran. (Photo: Armin Linke)

-

Marlies Wirth is a curator and art historian based in Vienna. Since 2006 she has worked at MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art where she curates exhibitions as well as temporary interventions and performances in the fields of art, architecture, design and fashion. With a focus on conceptual, site-specific, research- and time-based art and architecture she is also interested in the interconnection of contemporary art production and museum collections as well as new forms of exhibition display outside the classic museum presentation.

Wilfried Kuehn is an architect and curator based in Berlin and Vienna. He taught exhibition design and curatorial practice at the Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design from 2006 to 2012. With Simona Malvezzi and Johannes Kuehn he founded the Berlin based partnership Kuehn Malvezzi in 2001. Public space and the Arts are the main focus of their work as architects, designers and curators. Works include the extensions of the Museum of Contemporary Art Hamburger Bahnhof and of the Museum Berggruen in Berlin and the Julia Stoschek Collection in Düsseldorf. Kuehn Malvezzi has featured in a number of exhibitions, amongst others in the 10th, the 13th and the 14th Architecture Biennial in Venice and at Manifesta 7 in Trento. Together with artist Armin Linke Wilfried Kuehn curated and designed the exhibition 'Carlo Mollino - Maniera Moderna' at Haus der Kunst, Munich in 2011.

The exhibition Hollein (25 June – 5 October 2014) at the MAK in Vienna (link) was prepared in collaboration with the Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach (link), currently showing the exhibition Hans Hollein: Alles ist Architektur [Hans Hollein: everything is Architecture] (13 April – 28 September 2014).

Forthcoming book:

Hans Hollein

photographed by Aglaia Konrad and Armin Linke

Ed. Wilfried Kuehn, Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Susanne Titz, Marlies Wirth

MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art, Vienna

Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach

Mousse Publishing, Milan

2014

German/English, ca. 120 pages

moussepublishing.com

Hollein’s Protagonist

The column is the model based on Hollein’s skyscraper drawings from 1959; it runs through the Olympic Village as a Media Line and surfaces again as vitrine in Tehran and palm tree in the Austrian Transport Office in Vienna. At the first Architectural Biennale in Venice in 1980 the column was Hollein‘s protagonist. His contribution to the Strada Novissima exhibition curated by Paolo Portoghesi was an essay about the potential of columns to generate new spaces.

From the starting point of the contextual columns of the Corderie in the Venice Arsenale (the site of the 1980 Biennale), Hollein installed four of his own altered columns, each of which had morphed into a different object:a bare tree, a tree covered in dense foliage, a suspended stone column whose bottom half had been lopped off, and a huge model of Adolf Loos’ design for the Chicago Tribune Tower. Hollein inverts Loos’ readymade by reverting the classical column that Loos had transformed into a skyscraper back into a column again. Through changes in scale or material, through shifts from one context to another, Hollein activates the potential of objects, using them to generate new environments and create meaning and spaces that transcend the preexisting architectural programme.

(Translated by Lucy Powell)

(Translated by Lucy Powell)Strada Novissima, “The Presence of the Past” exhibition, Venice Biennale, 1980. (Image © Hans Hollein archive)

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Don‘t fight forces, use them.«

Richard Buckminster Fuller

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents